Music Was Magic Until the Ringing Began

By Gabriel Heredia

By Gabriel Heredia

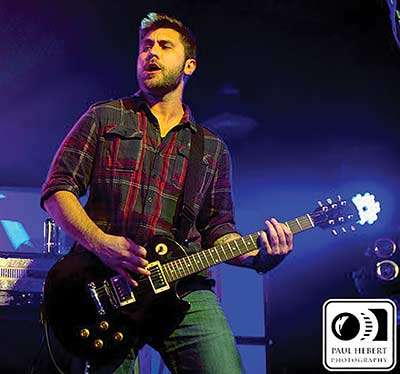

As a musician and songwriter, I listen to music a bit differently from the way people do if they don’t play music or compose. I hear the song as a whole, then tune in to a certain instrument and follow that sound to the next one. I home in on the beat, single out the snare drum, kick drum and how they blend with the synth sounds. I pick up the echo on the voice, the harmonies, then it all comes back together as a whole and I enjoy the song even more. That sonic breakdown would help me write my own songs, and for me there was nothing better than plugging in my instrument, turning it up, and strumming a chord. It would be so loud that the room would shake. Add in the bass guitar, then drums; my songs would begin to roar from the speakers. You literally feel the music in your bones. Everyone is in sync and you’re in your element, nothing else matters. There is a sense of joy, freedom, lightness as you play your music almost in a trance. Two or three hours later, rehearsal is over and there it is—the inevitable ringing in your ears—but you don’t mind because you know by tomorrow it will be gone. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Ten years ago, my life consisted of waking up and heading to the recording studio. During the day, I would edit dialogue for TV or features, record ADR (automated dialogue replacement) with actors, or mix on an incredible mix stage for a few days at time or tune and tweak someone’s movie and bring it to life sonically. I’d wrap up my day and head to rehearsal. To me, I was living the dream.

Late 2008, after a typical day of studio work and rehearsal, I came home with the usual ringing in my ears, confident that by the morning it would be gone. The next day it was still there, but I didn’t worry because sometimes it took a few days to fade away. By the third day, not only was it ringing but it was also getting louder to the point that I couldn’t think or concentrate. That’s when I really started to worry, but I still had a job to do.

While I was on the mix stage, fine-tuning the sound for a feature, the client asked me to stop and listen for a hissing sound in the dialogue. I played back the scene and heard nothing, so I figured he was mistaken and continued. He interjected, “Hey, Gabe, stop for a second. Are you sure you don’t hear that? It’s pretty loud and it’s in the whole scene. Can we remove it?” I couldn’t hear the sound because the ringing in my ears was so loud it was drowning it. I needed to hear to be able to do my work and I couldn’t; that moment was the beginning of the end.

I went home that night began researching online and discovered “tinnitus.” In the first paragraph, I read, “There is no cure and it’s permanent but treatable.” I felt a cold chill run down my spine and couldn’t breathe. The further I read, the more I realized that I had made a colossal mistake by not protecting my ears all those years. The next six months would be the most difficult of my life. Doctor visits were dead ends and the only “remedy” was antidepressants and advice that I learn to live with it. I found myself in the emergency room about twice a month suffering from massive panic attacks caused by the ringing as it got louder. I could only sleep in 30-minute to 1-hour spurts, waking panicked as the ringing blared. It was awful.

I went home that night began researching online and discovered “tinnitus.” In the first paragraph, I read, “There is no cure and it’s permanent but treatable.” I felt a cold chill run down my spine and couldn’t breathe. The further I read, the more I realized that I had made a colossal mistake by not protecting my ears all those years. The next six months would be the most difficult of my life. Doctor visits were dead ends and the only “remedy” was antidepressants and advice that I learn to live with it. I found myself in the emergency room about twice a month suffering from massive panic attacks caused by the ringing as it got louder. I could only sleep in 30-minute to 1-hour spurts, waking panicked as the ringing blared. It was awful.

I left the studio to my partner. And although I continued to write and play music (with ear protection this time), it would never be the same because I was now afraid of the thing that I loved the most. I thought about suicide because if the ringing got any louder, I knew I wouldn’t be able to handle it. I was depressed and anxious. My emotions seesawed back and forth constantly.

In the following months, my sister, who was my roommate at the time, helped me get out of the house. I started eating healthier, cut out alcohol, exercised, practiced yoga, discovered meditation, and took vitamins. It made a difference. The ringing wasn’t as loud and I was a little more comfortable with it. Nights, however, were still terrible. And I now sleep with the TV on to mask it.

What struck me the most during this period was I couldn’t find better information online about tinnitus. Facebook was still in its infancy and the internet was 1.0. Myspace was a thing, but no one on that platform talked about tinnitus. It took another eight or nine years for me to discover the American Tinnitus Association.

For me, that was a multifaceted problem because I had seen at least seven different doctors and audiologists and no one told me about the ATA. When searching online, I was inundated with snake-oil treatments. Nobody in my circle of friends had ever suffered from tinnitus, so it was extremely isolating.

In the years before finding the ATA, I just winged it, staying healthy and wearing ear protection. My band disbanded because it just wasn’t the same. During the ensuing years, I would try to keep my finger on the pulse of all things tinnitus—be it on social media platforms or forums—and started to notice an increase in young adults suffering from tinnitus. That’s when I knew I had to try to do something because there was a void in the media on the issue. Tinnitus is a complicated topic, it’s scary, it’s permanent, and there isn’t a quick-fix cure. All of that is scary to people, especially young adults who feel invincible.

In the years before finding the ATA, I just winged it, staying healthy and wearing ear protection. My band disbanded because it just wasn’t the same. During the ensuing years, I would try to keep my finger on the pulse of all things tinnitus—be it on social media platforms or forums—and started to notice an increase in young adults suffering from tinnitus. That’s when I knew I had to try to do something because there was a void in the media on the issue. Tinnitus is a complicated topic, it’s scary, it’s permanent, and there isn’t a quick-fix cure. All of that is scary to people, especially young adults who feel invincible.

Instead of turning a blind eye—or a deaf ear—I think well-known musicians, athletes, movie stars, and anyone else in the spotlight need to embrace the topic so it becomes part of mainstream conversation. They, too, are vulnerable to developing tinnitus from the work they do. Think of William Shatner, will.i.am, Eric Clapton, and so many others. If I had known then what I know now about the risks of loud sound, I would’ve always worn hearing protection. It would have been a $2 solution to something that will dog me for the rest of my life.

Any person blasting their headphones, standing in front of the speakers at a show, or taking their children to a loud concert should be aware of the risk and either turn the volume down on the music or wear earplugs at the concert; it’s so worth it. SO WORTH IT. If you’re in doubt, ask the thousands of people on Facebook or Reddit who talk about their struggles with tinnitus; how they wish they could go back and protect their hearing.

I feel like we’re just at the beginning of getting the word out on the importance of hearing protection and tinnitus awareness. That’s okay in some sense because it is now easier than ever to have a voice online that—with the right message—will cut through the noise of the internet. My message to you is when you’re at a concert or sporting event or any place you know is going to be loud, bring earplugs, or at least give your ears a break every 30 to 40 minutes by stepping away to take a break from the sound. It can make a world of difference.

Gabriel Heredia, 38, is a former sound re-recording mixer and music producer, living in Sherman Oaks, California. After developing tinnitus, he changed careers and now edits and produces unscripted content for networks, including Bravo, Food Network, ESPN, CNN, Discovery, and many more. In his 10th year with tinnitus, he considers himself habituated. He uses $10 earplugs available on Amazon whenever he’s in a loud environment. He began using hearing aids three years ago and found they helped with hearing in frequencies affected by hearing loss, which reduced the perception of tinnitus. Heredia produced the American Tinnitus Association’s first tinnitus awareness clip last year as part of his commitment to making a difference and raising awareness online among teens and young adults.