More On:

Oscars 2022

-

'Slow Horses' Writer Will Smith Wins Emmy, Doesn't Slap Anyone: "Despite My Name, I Come In Peace"

-

Rob Schneider Resurrects Will Smith Oscars Slap Drama As He Goes Off On The Actor: "He's Really An A**hole"

-

Stream It Or Skip It: 'King Richard' on Netflix, The Movie That Won Will Smith An Oscar (and Inadvertently Led To The Slap)

-

Stream It Or Skip It: ‘Hans Zimmer: Hollywood Rebel’ on Netflix, A Short Doc About One Of Hollywood's Leading Composers

Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer scored his first windfall by pawning his wife’s jewelry to purchase the New England rights to D.W. Griffith’s loathsome The Birth of a Nation. He took his filthy lucre west, built MGM, and in order to bolster the self-esteem of actors who were still considered to be players in an embarrassing fad, created an excuse to throw a party for them every year. Mayer, after importing a lot of writers with the advent of talkies, responded to the threat of unionization by founding an organization called the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, mainly to centralize labor negotiations and to kill two birds by throwing an annual party to distribute the Academy’s awards. These parties gave these unbelievably privileged and feted creatures of the silver screen the chance to manufacture an image of themselves as glamorous, wealthy, and — perhaps most precious to them — classy. (Explanation, in part, as to why the red carpet is so integral a tradition.) The Academy Awards, in other words, are a masquerade built on a lie; this says a great deal about their value as an arbiter of quality. Sometimes they get it right, but it seems like when that happens, it’s more due to an accidental confluence of factors than anything intentional (like, say, good taste).

The voting body, revealed in recent years to be overwhelmingly white and elderly, generally votes for things that appeal to the white and the elderly. If the voting body were not so overwhelmingly old, it’s fair to say that the list of nominees and winners would look predictably different. Many of these voters have been doing it a long time, which explains why the picks were a little fresher in the ’70s; and also why they were so rancid in the 2010s.

In 2022, with a strong push to diversify its voting body, we’re rounding in on the possibility of another Asian film winning Best Picture; you’ll recall that Korea’s Parasite took the award in 2020. In between, Chinese-American Chloe Zhao, daughter of a billionaire Chinese industrialist, won Best Picture and directing honors for Nomadland, her equivocal picture about subsistence workers. Can a shift in diversity numbers explain an increase in nominations, and wins, for non-traditional (read: foreign, woman-directed) pictures? Sure, but it’s hard to say – one thing old white folks like is to feel like they’re demonstrating sensitivity to social issues without also being inconvenienced or made to feel uncomfortable by them. Picking foreign films or films about people who have chosen to be poor slide right into the sweet spot of giving at the office without volunteering in the soup kitchen.

How this year’s surprise, dark horse nomination of Ryuske Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car performs will serve as a good barometer for how far the diversity push has truly impacted the Academy’s long-moribund progressiveness. Easily the best film of the year among films released in the United States, Drive My Car is an adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short story – a long, painterly meditation on grief and acceptance structured around, and using as a metaphor, a multi-cultural/multi-lingual production of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.” It’s the opposite of an “Oscar Bait” film: showcasing no big name Western stars (indeed, much as with Parasite, the Academy’s largesse goes only so far as to nominate the picture, not anyone in the cast), while being no one’s idea of an audience-pleasing bit of “prestige” issue cinema. If Drive My Car wins, I’ll put down my hardwired suspicion for a moment and acknowledge that things might actually be getting better (even if minorities are still sorely underrepresented in the major categories and, pointedly, in the boardrooms where decisions about what does, and does not, get time on screen in an American movie are ultimately made). I say all this to say that, just like every year, this is either a tolerable-to-good year for this award’s credibility, or it’s a Green Book/Forrest Gump year where everyone who isn’t embarrassed now will be a little embarrassed later.

With all that being said, here’s a film from each decade from the 1930s through to the 2010s where the Academy absolutely nailed it.

The 1930s

'It Happened One Night'

Though I’ve always had a soft spot for Charles Laughton’s Captain Bligh in Frank Lloyd’s Mutiny on the Bounty, it seems clear the best, best picture winning film of the 1930s is Frank Capra’s still-delightful It Happened One Night. In it, Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert as a journalist and an heiress hitchhike across pre-Code America as they overcome class distinctions and an initial dislike for one another to fall in love. Sprightly, naughty, and in its interest in the income gap, still depressingly-relevant. It’s one of the great romantic comedies.

The 1940s

'The Best Years Of Our Lives'

Maybe the best decade of winners, and losers, overall — my heart wants to pick Hitchcock’s first American film, Rebecca, but I think the answer here is William Wyler’s towering The Best Years of Our Lives, which revolves around a trio of soldiers returning from war, disabled physically and emotionally, to find that their families have changed in their absence as well. A stunning, emotionally lacerating rebuke of the war propaganda period in Hollywood just ending, it’s a mature work about a country passing from innocence into experience. You really couldn’t go wrong with Casablanca, Mrs. Miniver or How Green Was My Valley, either — and of course Citizen Kane which didn’t win but, you know, Orson Welles was young and was not popular with the voting body.

The 1950s

'On The Waterfront'

A particularly weak batch of winners right here in the heart of the Golden Age coinciding with, not coincidentally, the peak of Hollywood’s image-massaging machinations, so make mine Elia Kazan’s controversial, self-serving apologia On the Waterfront. For all the ickiness of a director who named the names of his friends to the House Un-American Activities commie witch hunt, making a movie about a longshoreman who heroically testifies against his corrupt union bosses, the film remains an elegiac portrait of a limited man who makes decisions that get people killed. Marlon Brando is incredible. Eva Marie Saint is incredible. And Budd Schulberg’s script includes Brando’s “I coulda been a contender” speech: one of the great moments in motion picture history.

The 1960s

'The Apartment'

Billy Wilder’s scabrous sex and corporate culture satire The Apartment is the bleakest of black comedies, pairing Jack Lemmon with an impossibly fresh Shirley Maclaine against a reptilian Fred MacMurray. Wilder’s films were always nasty bits of work, and this is, while not the nastiest (Kiss Me, Stupid is several degrees nastier), certainly emotionally difficult at times to endure. The ’60s were interesting as films like The Hustler, Bonnie & Clyde and Dr. Strangelove were nominated but lost to inferior product.

John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy is a close runner-up and serves as a fascinating bookend to a decade that began with a man loaning his apartment to his boss for his boss’ extramarital affairs, and ends with a male gigolo and his mortally-ill buddy, trying to survive in the big city. The quick-eyed will notice that Jon Voight’s cowboy, Joe Buck, keeps a poster of Paul Newman’s Hud in his locker – a visual reference to Hud’s thesis that the face of a nation changes according to the men we choose to emulate.

The 1970s

'The Godfather: Part II'

The greatest period of film any time and any place in the world produced a truly tough call. I’m going with The Godfather: Part II here, though the first The Godfather is also incredible, as are films that lost to them like Cabaret and The Conversation. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is shockingly durable, as is Rocky who was once derided for winning over Taxi Driver, but has proven over time to be, while obviously dissimilar, a masterpiece of arguably similar weight and certainly equal – maybe even superior – influence. Annie Hall is still great but if we’re looking for genuine upsets, Kramer vs. Kramer is better than All That Jazz and Apocalypse Now in no universe. It was too soon for a brutal reckoning with Vietnam in 1979 and Bob Fosse’s savage auto-appraisal is discomfiting even now forty-some years later.

The 1980s

'Ordinary People'

I’m throwing in with Robert Redford’s Ordinary People for this decade, a film again overshadowed in its critical consideration by a film it beat out for the prize, Raging Bull. A shame one of them wasn’t a year later, as either of them are better than Chariots of Fire. Honestly, Raiders of the Lost Ark should have won over Chariots of Fire, just as E.T. should’ve taken Gandhi, and Broadcast News should have beaten the very good (but not Broadcast News-good) The Last Emperor.

About Ordinary People, though: Its cast — Timothy Hutton, Mary Tyler Moore, Donald Sutherland, Elizabeth McGovern, and Judd Hirsch — are, to a one, sublime in playing out this melodrama about a family trying to figure out its footing after tragedy and mental illness shake it loose from its comfortable middle-class moorings. It’s as emotionally caustic as Raging Bull; they’re essentially the same film in many ways, Ordinary People manages to be barbed from beneath a sheath of urbane civility. It’s incredible.

It bears mentioning that this is the decade where Driving Miss Daisy not only beat Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, but Lee’s Do The Right Thing wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture. It remains one of the most shameful chapters of Oscars history.

The 1990s

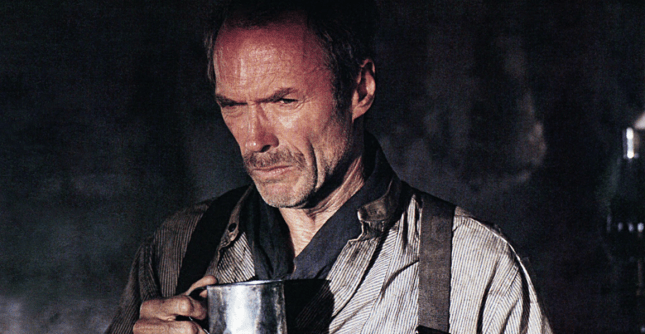

'Unforgiven'

The obvious choice is Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, which is indeed a technical marvel (as are all of Spielberg’s films), or Jonathan Demme’s effective serial killer/workplace tension flick The Silence of the Lambs, but make mine here Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, his thoughtful, pensive penance for a career built on vigilante characters known for their prowess as killers and rapists. Gene Hackman very nearly steals the show from Eastwood and Morgan Freeman as a corrupt sheriff trying to build a house and retire before karma catches up with him. A tragedy of a specific kind, it felt like a farewell to this stage of Eastwood’s career and remains, along with A Perfect World, my picks for the best Eastwood-directed films of his long career. Pulp Fiction should’ve won over Forrest Gump, of course; ditto The Thin Red Line or Saving Private Ryan over Shakespeare in Love, and Fargo over The English Patient.

The 2000s

'No Country For Old Men'

Another easy pick for the “aughts,” the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, beating out the great Paul Thomas Anderson film There Will Be Blood (which would have been an easy pick over any of the other nominations over the course of the rest of the decade). The Coens prove with this film, if proof were necessary, that they are, along with Jane Campion, the best literary critics among living filmmakers. Their adaptations (O Brother Where Art Thou?, True Grit) demonstrate a deep understanding of not just the work they’re adapting, but the authors’ entire bodies of work. No Country For Old Men is not just a graceful treatment of Cormac McCarthy’s book about the dismal tide overtaking mankind, but of McCarthy’s entire career of documenting the transition from the traditions of the old to the horrors of the new.

The 2010s

'Moonlight'

A rough decade that saw a marked decline in esteem for this award leading directly to its recent reckoning with diversity and sexual harassment among its ranks, find here travesties like Green Book winning Best Picture over Spike Lee’s BlackkKlansman, The King’s Speech winning over True Grit, and Spotlight winning over Mad Max: Fury Road. My pick for the decade is Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight – a film whose poetry only increases with time in its telling of a young man who finally finds out who he’s supposed to be when he meets the man of his dreams. Sensitive, progressive, gorgeously framed and executed, it’s a watershed moment that pushed change in a meaningful, and highly visible, direction.

Walter Chaw is the Senior Film Critic for filmfreakcentral.net. His book on the films of Walter Hill, with introduction by James Ellroy, is now available for pre-order. His monograph for the 1988 film MIRACLE MILE is available now.

Fun

Fun Frisky

Frisky Nostalgic

Nostalgic Intense

Intense Adventurous

Adventurous Choked Up

Choked Up Curious

Curious Romantic

Romantic Weird

Weird