Woman sues San Francisco after DNA from rape kit was used to arrest her

A woman whose DNA from a rape kit was used by cops to arrest her for an unrelated burglary filed a federal lawsuit against San Francisco on Monday, alleging the police invaded her privacy.

The DNA of the woman, known as Jane Doe, was stored by the SFPD as part of a domestic violence and sexual assault case in 2016. According to her lawyer, Adanté Pointer, the same sample was used to charge her with retail theft five years later.

The lawsuit claims that the victim’s DNA was entered without her knowledge or consent into a database used to identify perpetrators in other crimes.

“This is government overreach of the highest order, using the most unique and personal thing we have — our genetic code — without our knowledge to try and connect us to crime,” Pointer said in a statement.

The suit says the database misused “thousands” of victims’ DNA, although it is unclear if there were other arrests.

Jane Doe’s case led to a widespread revelation of the practice within the SFPD earlier this year, when then-DA Chesa Boudin heard of her arrest and declined to prosecute her.

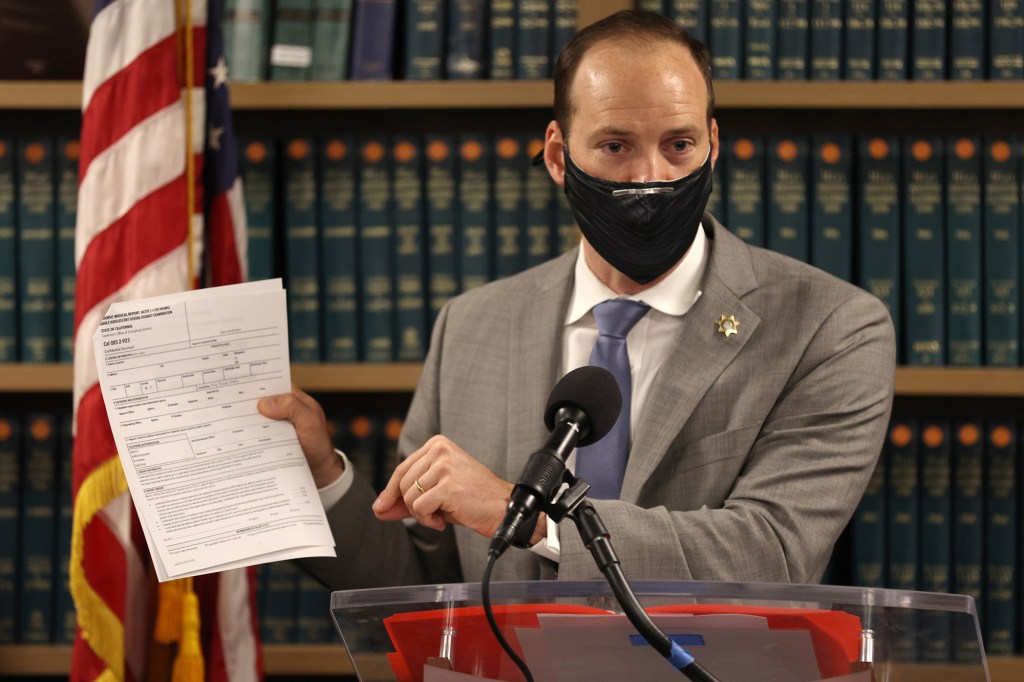

Speaking at a press conference in February, Boudin called the DNA evidence the “fruit of the poisonous tree” and an “egregious violation of victim privacy.” At the time, San Francisco Police Chief Bill Scott stated that he had ordered an investigation.

“We must never create disincentives for crime victims to cooperate with police,” he said.

Within days, the SFPD officially ended the practice of sharing victim DNA outside the crime lab.

There is already a federal law that prohibits the inclusion of victims’ DNA in the national Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). There is no state law in California prohibiting investigators from retaining victim profiles and searching them in connection to different crimes later on.

Last month, California lawmakers approved a bill that would forbid DNA collected from sexual assault survivors and other victims for anything other than identifying the perpetrator. Local police would also be banned from keeping and searching victim DNA in order to incriminate them in unrelated investigations.

The legislation is pending before Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Speaking to The Post early Tuesday, Pointer said the case is “personal” for his client.

“She went to the police when she was in need, at one of the lowest points of her life,” he said, describing the 2016 incident.

“It took a lot for her to call the police.”

Though the initial rape kit did identify the perpetrator, Pointer said the assailant evaded justice when his client declined to testify in court.

It was not until five years later, when police were called to her residence by neighbors reporting an alleged domestic dispute in 2021, that the victim even knew law enforcement still had her DNA sample.

“They ran her name and went, ‘Oh, we have a warrant for you,’” Pointer said.

“As opposed to providing the protection, they treated her as a criminal.”

Pointer said his client could not make bail, so she languished in jail for weeks before Boudin dropped the charges.

“[The police] re-victimized her again,” he said.

The fact that the victim is a black woman, Pointer said, only adds to the “long history of distrust” people of color have with law enforcement, “for all good reasons.”

While he said the case “has implications beyond race,” he did say the incident was “another affront to the community.”

Pointer hopes the potential changes wrought by the story will have wide-reaching consequences.

“The criminal justice system has turned into a criminal injustice system,” he said.

Pointer’s concerns echo those of Jennifer Lynch, a surveillance litigation director for the Electronic Frontier Foundation who penned an article about the exploitation of victim DNA earlier this year.

Writing in response to Boudin’s announcement, Lynch pointed to other local “rogue” databases, including an infamous “spit-and-acquit” program in Orange County. The issue, Lynch argues, hinges on how police officers push the boundaries of consent when collecting genetic material.

“A law that merely addresses DNA collected from rape victims is not enough to prevent other improper and unconstitutional DNA searches in the future, both in San Francisco and throughout the country,” Lynch wrote.

“Any legislation that’s introduced must also address the consent issues more broadly.”

Jen Kwart, a spokesperson for San Francisco City Attorney David Chin, said in a statement to Bloomberg that the city “is committed to ensuring all victims of crime feel comfortable reporting issues to law enforcement and has taken steps to safeguard victim information.”

Kwart also noted municipal legislation approved this spring prohibiting San Francisco police or other departments from sharing or storing crime victims’ DNA in any database not subject to federal or state rules.

The San Francisco Police Department did not return a request for comment.