Alvin Bragg’s ‘complicated’ case against Trump is unchartered legal waters

The criminal case that Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg brought against Donald Trump is “going to be very complicated” and will likely require judges to set new legal precedent, experts say.

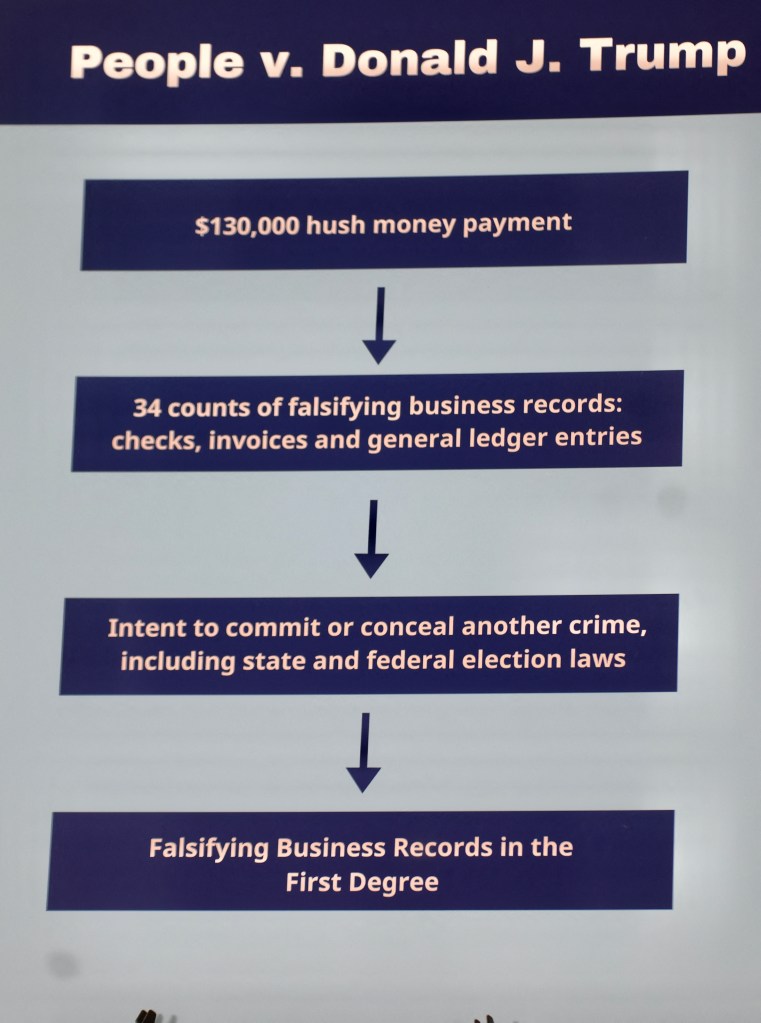

Trump was indicted on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records over him allegedly failing to disclose a $130,000 “hush money” payment to former porn star Stormy Daniels as a campaign contribution since it protected his 2019 presidential run. He pleaded not guilty to the crimes at his arraignment Tuesday.

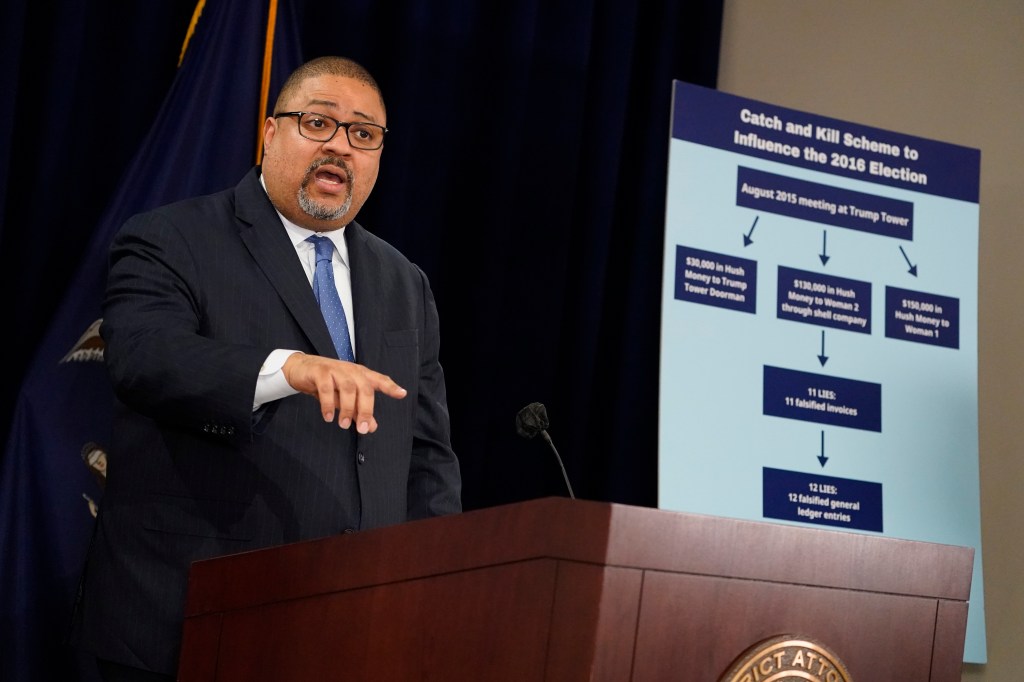

The charge of falsifying business records is a misdemeanor that Bragg’s office elevated to a felony crime by alleging the former president made the false records with the intent to commit another crime – which in this case was allegedly violating campaign or election law.

The 45th president allegedly directed the payment to be made to Daniels and another $150,000 payment to former Playboy model Karen McDougal in 2016 in the lead-up to the election to silence both women about their claims they had affairs with him. He then lied in business records to disguise the payment to Daniels as legal costs, prosecutors say.

“A business records charge is a really common white-collar charge,” former Brooklyn prosecutor Adam Uris said. “It’s a method of insuring that businesses don’t cook the books.”

“Alvin Bragg elevated it to a felony by using a very little used legal theory that says if you’re falsifying the business records to hide a crime, it makes it a felony,” Uris explained.

Uris and legal experts said it is rare to use an alleged federal election-law violation to increase the state law misdemeanor of falsifying business records to a felony.

“The tricky part for Bragg’s prosecution is that the crimes he suggested at the press conference – which were campaign finance-related and election law-related – both deal with federal crimes,” Uris said. “What they are going to have to test out in court is whether you can charge someone at a state level for committing a state-level offense behind a federal crime.”

Uris and other experts said the approach goes into uncharted legal waters, requiring rulings on issues that haven’t been decided on before – making what’s referred to in law as “a case of first impression.”

Former Manhattan prosecutor Michael Bachner said that while the DA’s office has brought similar cases in the past, those defendants pleaded guilty before the legal issues needed to be decided by a judge.

“This is going to be a very complicated area,” Bachner said. “It’s never been litigated.”

“This may be a case of what the courts call first impression, where the courts may have to decide whether a violation of federal law could be used to increase a state statute,” Bachner explained.

Uris said that because there is no legal precedent for this type of legal theory, Trump’s camp will likely make legal challenges, if he is convicted, that could land the case in New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals.

“If I were his lawyer, I would do whatever I could to prevent this case from going further,” Uris said.

Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Juan Manuel Merchan on Tuesday may have set the next court date for so far out, in December, to give time for the legal issues to play out, Uris said.

“He set a very long adjourn date … It is very unusual,” Uris said. “My guess is it’s because [Merchan] understands the legal issues are going to be challenged.”

The experts also said Trump’s case has some similarities to the 2012 case against former North Carolina Sen. John Edwards, who was accused of carrying out a milliondollar scheme to use illegal funds to cover up his affair and love child with Rielle Hunter while his cancer-stricken wife Elizabeth Edwards was dying.

Edwards – a onetime presidential candidate – was cleared by a jury on one of the corruption charges he faced and the remaining charges, which the jury were hung on, were later dropped by prosecutors.

“Both [the Trump and Edwards cases] involve allegations of hush money payments while both individuals were in the midst of a political campaign,” former Brooklyn prosecutor Julie Rendelman told The Post.

But one major difference between Edwards’ and Trump’s cases is that Edwards was charged federally and he was charged with an election-law violation, Rendelman said.

“I think Trump’s charges are a little bit cleaner,” Rendelman said.

Uris noted that the two cases are similar because “they both do feel politically motivated.

“They both deal with the defendants’ character,” he added. “It is highly questionable conduct that is immoral and unethical – but maybe not quite felonious.”

Uris said Bragg’s case “felt rushed” and came after he faced a difficult first year in office and pressure to bring a case with the public’s attention on Trump.

“Trump has been saying that this is a political hit job, and because it is such a stretch legally, it does feel like a political hit job,” he said.

If the case fails, Uris said he wonders what will stop politicians from carrying out this kind of alleged conduct in the future.

Still, “the threat of prosecution sometimes is more effective than the prosecution itself,” Uris said.