The following is an excerpt from the “1998 Yankees: The Inside Story of the Greatest Baseball Team Ever” by Jack Curry. This book is a comprehensive and behind-the-scenes look at a talented and relentless team that won an unprecedented 125 games and also won the Yankees’ 24th World Series title.

Rebel Without a Pause

The pitcher is alone on the mound. In that solitary moment, he decides what pitch he should throw and how he should throw it and where he should throw it. While he is surrounded by his teammates and is being studied by a batter, an umpire, and thousands of fans, he is all by himself. One man, one mound, one stage.

David Wells loved being on that stage and loved being in control of the game. That attention appealed to Wells, the rebel without a pause. Or a filter. Wells liked to work quickly. Get the baseball, get the sign, fire the pitch, and then do it again.

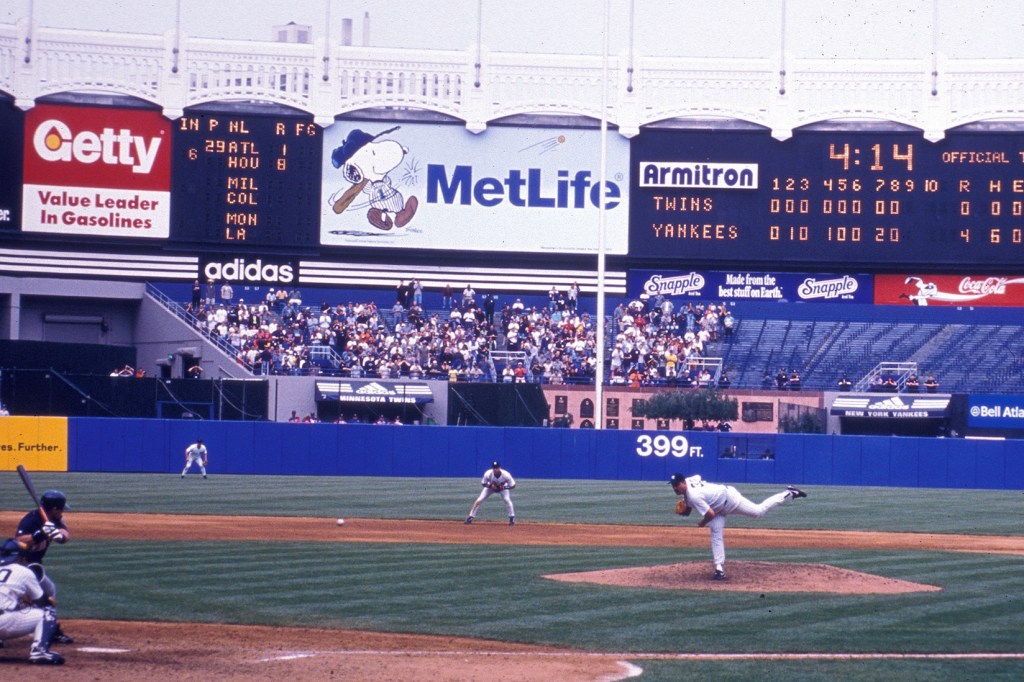

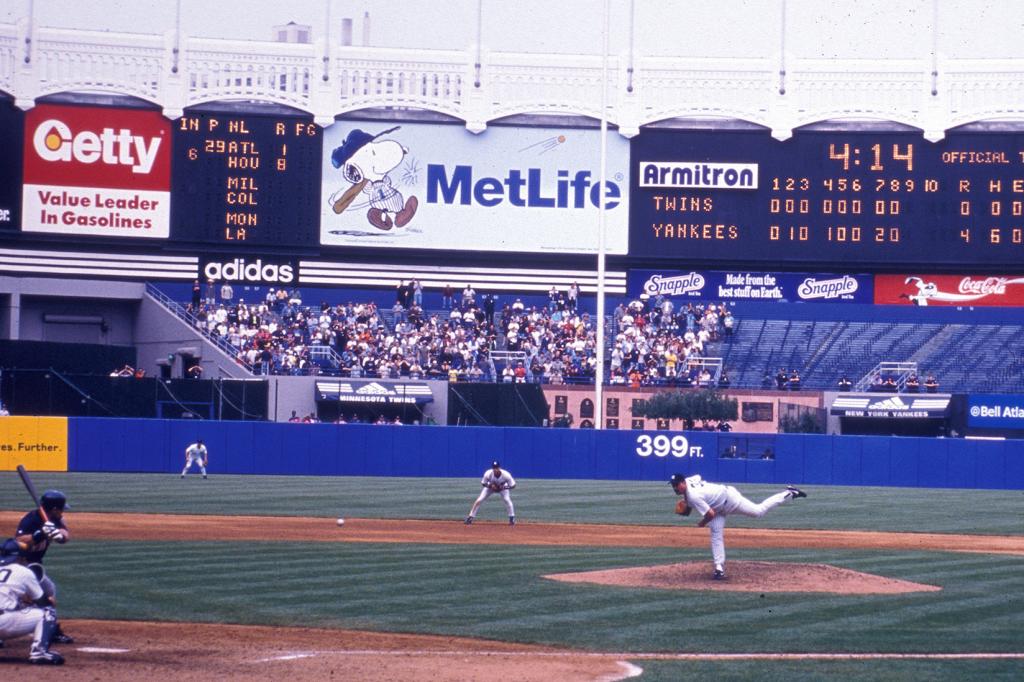

Because Wells preferred a quicker pace, he didn’t want to shake off a catcher’s signs. Wells had to be able to trust his catcher to think along with him so that Wells would see those flashing fingers and execute the pitch. The smoothest type of game for Wells would occur when he never had to shake off any signals, which is precisely what happened when Jorge Posada caught Wells’s perfect game against the Minnesota Twins on May 17, 1998.

“Didn’t shake him off once,” Wells said. “Jorge was perfect that day.”

But, before discussing Wells’s day of perfection, it is necessary to discuss what happened 11 days earlier. Before perfection, there was imperfection, angst, and anger on a sweltering night in Arlington, Texas. Before Wells, the burly and blustery left-hander, threw the 15th perfect game in major league history, he wandered off the mound in the third inning after nearly blowing a 9–0 lead. He was pissed off at his manager, his manager was pissed off at him, and things were far, very far, from perfect.

It was 94 degrees at game time, which was even steamier than usual for a May night in Arlington and wasn’t comfortable for a 240-pound-ish pitcher known as Boomer. There is heat and then there is Texas heat. It’s broiling and suffocating. At least it’s not 104, Wells thought to himself as he prepared to face a lineup that included Juan González, Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez, and Will Clark.

The Yankees, those rampaging Yankees, scored nine runs in there first two innings to give Wells an early cushion. Wells had retired six of the first seven batters and was cruising. This was destined to be a night for Wells and the Yankees to keep cruising. Get the ball, get the sign, throw the pitch, and then do it again. The Yankees had won 21 of their last 23 games. What could go wrong?

It took one pitch for Wells to get the first out in the third, but then everything about the night changed. A lot also changed about Wells’ already strained relationship with Manager Joe Torre. The Rangers followed with two singles and a walk to load the bases. After a groundout made it 9–1 and put Wells within one out of escaping, the pitcher unraveled.

On the mound, Wells kept pulling the shoulders of his sweaty gray jersey toward his neck so that the number 33 on his back was almost colliding with his cap. Gonzalez scorched a liner that glanced off second baseman Chuck Knoblauch’s glove to deliver two runs. Later, Rodríguez rapped a single past shortstop Derek Jeter to drive in two more. Finally, Mike Simms poked a two-run homer off the right field foul pole and, suddenly, it was 9–7. Nine Rangers came to the plate, seven scored and six had hits. Wells wasn’t finishing hitters, wasn’t focused enough, and seemingly wasn’t competing in the way Torre expected him to compete.

Looking irritated in the third base dugout, Torre bolted from his seat, took brisk steps across the dirt and grass and pointed toward the bullpen. Wells lifted his arms in disgust, looked toward the outfield and didn’t want to see Torre or speak to Torre. When Torre reached the mound, Wells gave him the baseball as if he was returning an undercooked steak, never made eye contact with his manager, and marched away.

“I was going good and I squandered it and Joe got pissed,” Wells said. “It’s not like I’m trying to give it up. You know? Stuff happens. It wasn’t cool and Joe and I kind of got into it. But do you know what the thing was? Joe never did that to anybody else. He would never do it to Coney or Pettitte or El Duque or anybody. He had it out for me for some reason.”

Really?

“My goal was to try and treat everybody fairly,” Torre said. “But I was trying to find the right key to David Wells. I really treated David the only way I knew how. Was it different? At times, it probably was.”

Even after the Yankees eked out a wild 15–13 win, Torre was quizzed about Wells. Torre was aggravated with Wells’s demeanor and said, “I didn’t like the way Wells was walking around on the mound and kicking at it and going slow and just really had bad body language.” And then Torre said Wells “looked like he ran out of gas. Maybe he’s out of shape.”

Once Wells learned that Torre had mentioned his conditioning as a possible reason for his disappointing outing, he was incensed. There were a lot of buttons to push to infuriate Wells. His weight was one of the hottest buttons.

“I was 18–4 that year and you’re going to attack me about my conditioning?” Wells said. “Again, that’s just an attack on me because you’re pissed off. You don’t attack a guy’s physique. I’m a big guy.”

Eager to retaliate with words, Wells told David Cone, his close friend, about his plan to criticize Torre to reporters. Cone, who had been in some toxic clubhouses and some harmonious clubhouses, knew how copasetic this clubhouse was and begged Wells not to rip Torre.

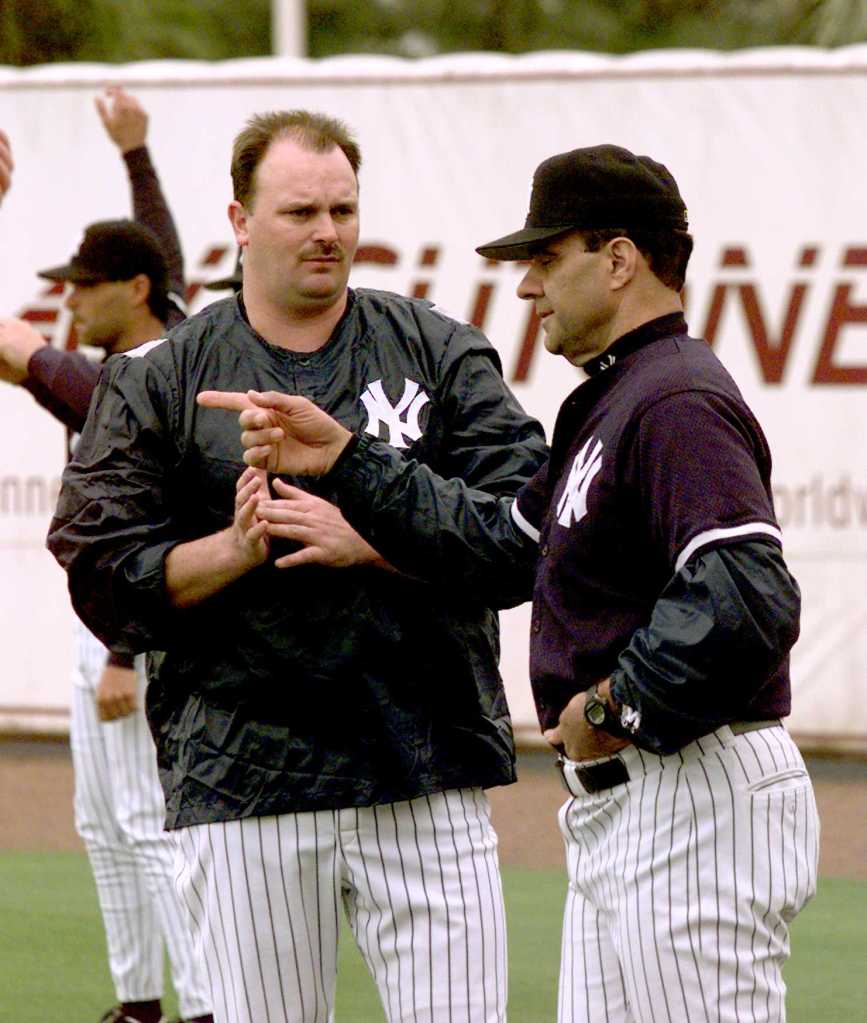

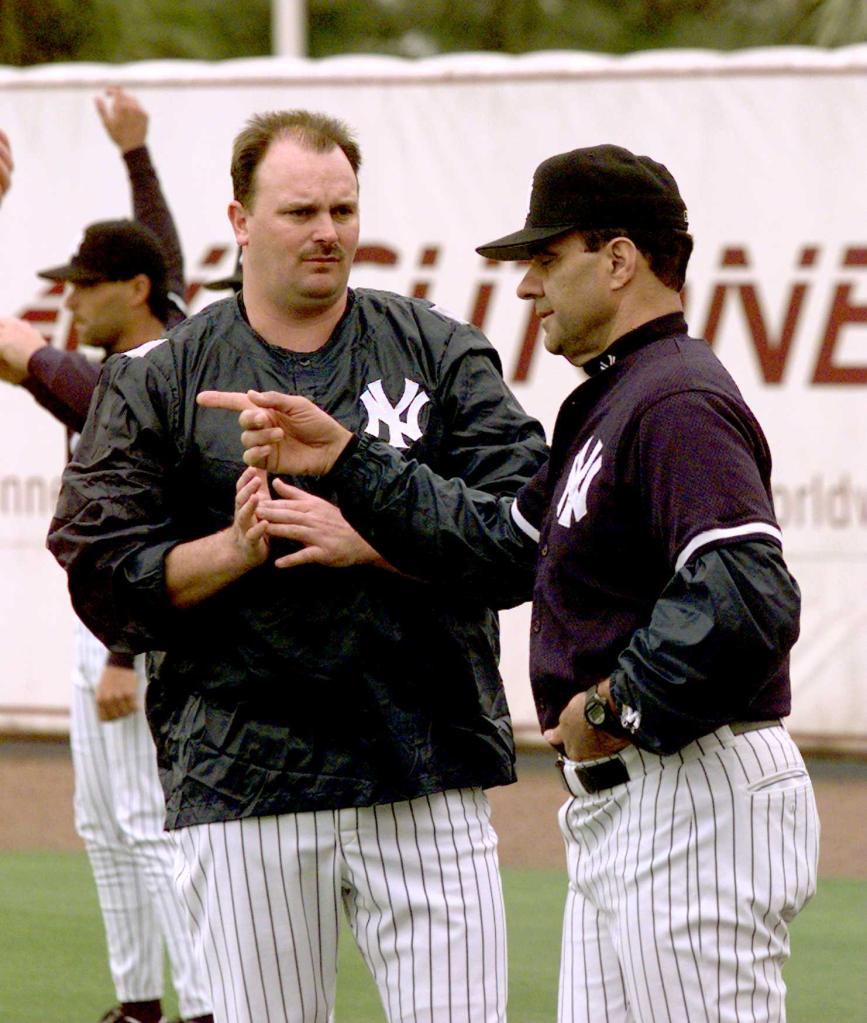

“You should set up a meeting with Joe and make sure that Mel is there too,” Cone told Wells, knowing that Stottlemyre could act as a mediator, a peacemaker or, at worst, a referee.

Three days after Wells’s lackluster start, he met with Torre and Stottlemyre at the Metrodome in Minneapolis. Torre reinforced to Wells that both he and Stottlemyre still had confidence in him, which was a meaningful gesture since Wells had a 5.77 earned run average at the time. Interestingly enough, after the conversation, Wells jogged along the warning track for 15 minutes and did sit-ups in the outfield, things he rarely did in public view. Torre had said he thought Wells needed to lose about five pounds. Wells disagreed. Torre added that Wells’ weight “wasn’t a big deal unless he’s going to have problems in warm weather.”

Many times, Torre would shake his head and would respond to something Wells said or did by simply saying, “That’s Boomer being Boomer.” As the manager, Torre was akin to the father who was trying to nurture 25 sons. Sometimes, one or more of them might be rebellious. Wells was that rebel.

While Torre was beloved by virtually all of his players, Wells didn’t attend those fan club meetings. Torre and Wells clashed a lot. Whether it was Wells playing Metallica too loudly in the clubhouse, Wells being late for pregame stretching or a meeting, or Wells leaving the field before batting practice ended, Torre had to repeatedly remind Wells about the team’s rules. And Wells wasn’t the type who wanted to be reprimanded.

“Joe just tried to manage me and that’s the wrong thing to do for a guy who is intense, who wears his emotions on his sleeve, and who isn’t going to take stuff from anybody,” Wells said. “And, to me, that’s one of the things I didn’t really like.”

Forever the nonconformist, Wells didn’t want the manager of the team to manage him. Huh? That’s not exactly how it’s supposed to work.

“That was just Wells’s personality,” Torre said. “Whatever the reason, he just, I guess, needed the attention. He dared you. He always challenged you.”

These days, Torre stressed that he and Wells are friendly to each other and that Wells has joked about how much he aggravated his manager. Still, while Torre searched for the right way to describe their relationship, he focused on the importance of trust.

“To me, trust is something you have to earn,” Torre said. “And I didn’t feel that from him. Other than giving him the ball. Man, he would go out there and pitch and he was a tough cookie. He was really tough.”

Tough, tenacious and, at times, callow. When Wells purchased a cap that had been worn by his idol Babe Ruth for $35,000, he mused that he would like to wear it in a game. Without getting permission from Torre, Wells donned the cap with “G. Ruth” stitched inside it for a game in June 1997. Torre made Wells remove it after one inning and fined him $2,500 for violating the uniform policy. Those kind of incidents exasperated Torre.

“He was just a brat, you know?” Torre said. “He was always pushing the envelope in a stupid way, in my opinion, because the game was more serious to me than maybe it was to him.”

But Cone understood Wells’s personality and understood how vital it would be for someone to oversee Wells and get the most out of his talented and durable left arm. That’s when Cone told Torre, “Let me handle Boomer. I’ve got him.” A relieved Torre agreed, saying, “Coney was the intermediary for me and Wells because we banged heads a lot. So I trusted Coney on taking care of Wells.”

And that’s how Coney and Boomer, baseball’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, became road warriors of a different type. They would travel with the Yankees and, once the airplane landed, they would split from the team and stay in a different hotel. With this strategy, Cone felt Wells would benefit from avoiding the bustling team hotel. The plan satisfied the rebel in Wells because it allowed him to snub the authorities and just do his own thing. As those wild and crazy trips were being hatched and executed, Wells did something amazing: He journeyed through nine innings of perfection.

Wells knew that he shouldn’t leave his Upper East Side apartment and go out partying on a Saturday night. Not when he was starting against the Twins the next day. Not with everything that had been swirling around him since his dreadful start in Texas and his clash with Torre. Staying in would have been the prudent thing to do, but Wells has never been prudent.

So Wells went out and ended up partying with Jimmy Fallon and other people who were affiliated with “Saturday Night Live.” Season 23 of “SNL” had wrapped a week earlier, but Wells described how he and Fallon and some others drank the night away.

“I really didn’t want to drink and Jimmy Fallon started hanging out and we started having drinks and, before you know it, I had probably had a whole bottle of vodka,” Wells said. “And we just kept drinking until like 5:30 in the morning.”

Fallon validated Wells’s story while interviewing Adam Sandler during an episode of “The Tonight Show” in 2022. In recounting the story, Fallon said, “We’re hanging out, we’re having some drinks, and we’re going late.” As both realized it was time to go home, Wells said he and Fallon had one of those end-of-the-night conversations that only inebriated folks can have.

“Who is leaving first?” Fallon asked. “You or me?”

Wells said, “Why don’t you leave first?”

Fallon responded, “No! You leave first.”

Round and round they went, turning an overdue exit into a slurring competition. Finally, Wells said he stumbled away from the bar and had a car service drive him to his apartment. He slept about two or three hours, woke up, bought a cup of coffee, and drove to Yankee Stadium.

“Man, if I was pulled over, I would have gotten a DUI,” Wells said.

Fortunately for Wells and anyone else who was on the road that Sunday, he reached the stadium without any incidents. But, as soon as Wells rumbled into the clubhouse, he had another problem. Cone stared at him, looked away, shook his head and finally said, “You stink.” Since the smell of alcohol was oozing from Wells’s pores, Cone told him to “go hide in the back” or the Yankees wouldn’t let him pitch.

Wells listened to Cone. But, eventually, he had to come out and pitch. With the top two buttons of his pin-striped jersey undone, Wells wobbled to the mound. He had no idea what to expect, but, after that first fastball pierced through the strike zone with solid velocity, Wells stood a bit steadier. He zoomed through the first inning on nine pitches. The 49,820 fans who came to the Bronx for a Beanie Baby promotion didn’t know they were about to get a much bigger prize.

Wells had another 1-2-3 inning in the second and struck out the side in the third, one on a curve, one on a fastball, and one on a changeup. Somewhere in the New York area, Fallon had slept off his night of drinking before awakening to a shocking sight.

“It’s gotta be 1 o’clock or 1:30 the next day,” Fallon explained. “I turn on the TV, and David Wells is pitching.”

At first, Fallon thought he was watching an encore version of another classic Wells game. But, very quickly, Fallon realized the man who was drinking with him until 5:30 a.m. was pitching a perfect game.

“It’s the craziest thing in the world to see that thing,” Fallon told Sandler on his show.

Sandler screamed, “He’s a mad man!”

The mad man rolled through the fourth, fifth and sixth perfectly and culminated a clean seventh by striking out Paul Molitor, who finished his career with 3,319 hits. Wells had retired 21 straight, perfectly orchestrated by Posada.

“When I put signs down that day, he threw the pitches exactly where I wanted them,” Posada said. “He was unbelievable.”

After a 1-2-3 eighth, the excitable fans stood and clapped and hoping for history in the ninth. Wells notched the first out a fly ball and the second on a strikeout and was within one out of perfection. The batter was Pat Meares, an infielder who was 5 for 23 against Wells in his career, including going hitless in his last 11 at bats.

Was this a dream? How could Wells, who was about 10 hours removed from his last gulp of vodka, be within one out of a feat that only 14 pitchers had ever accomplished to that point?

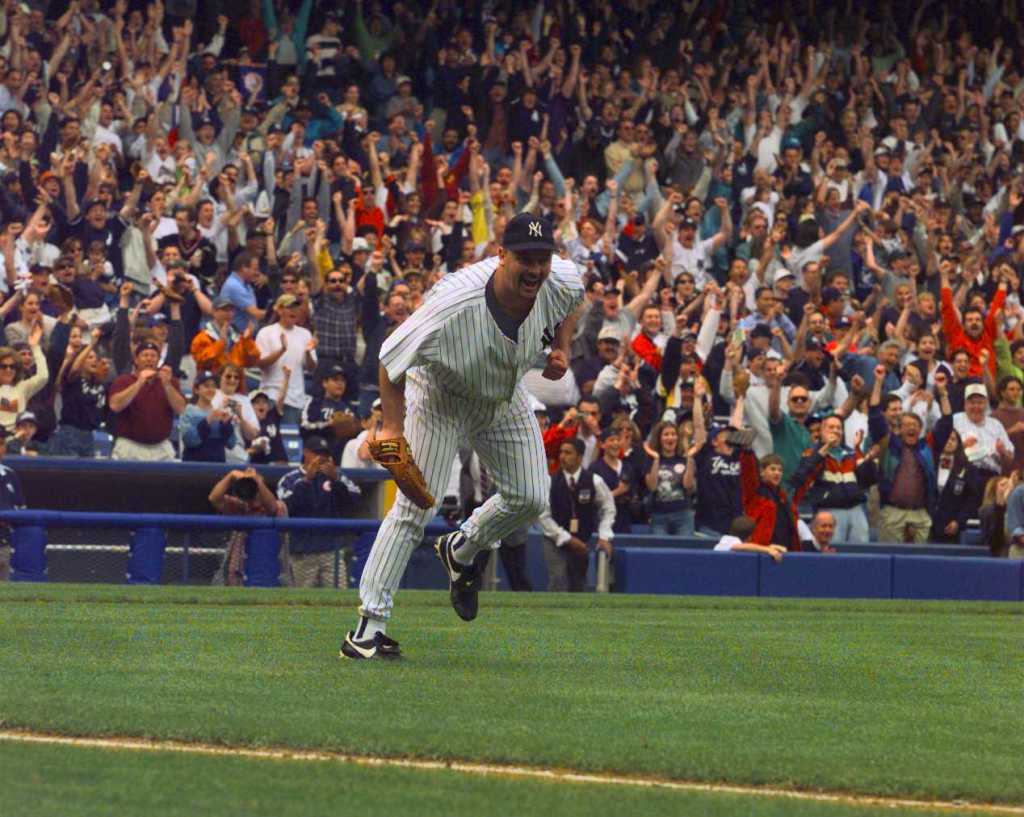

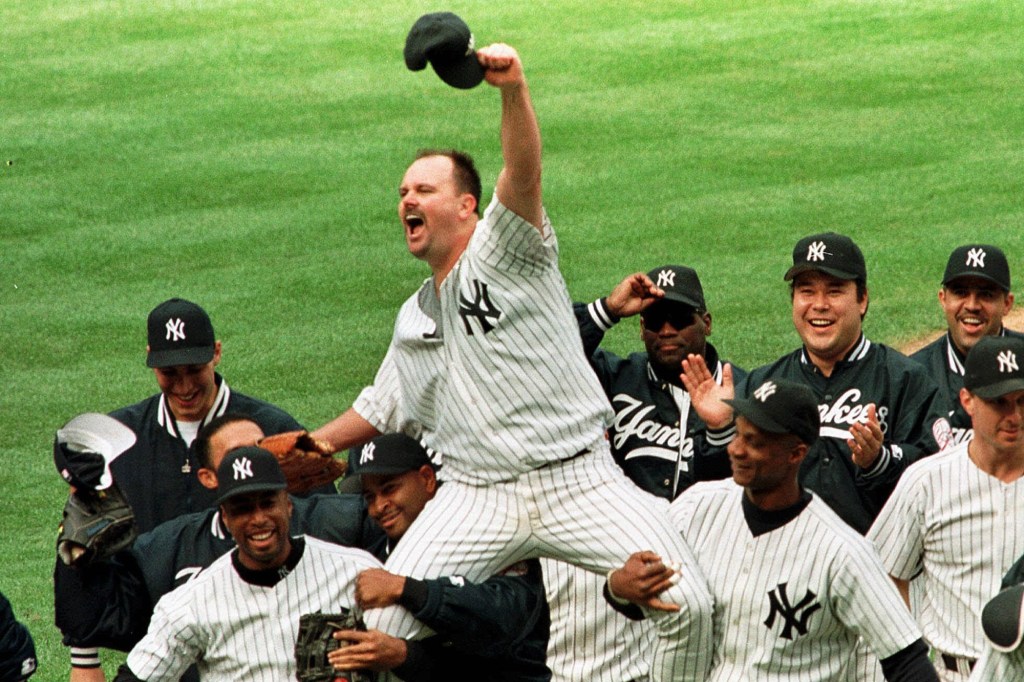

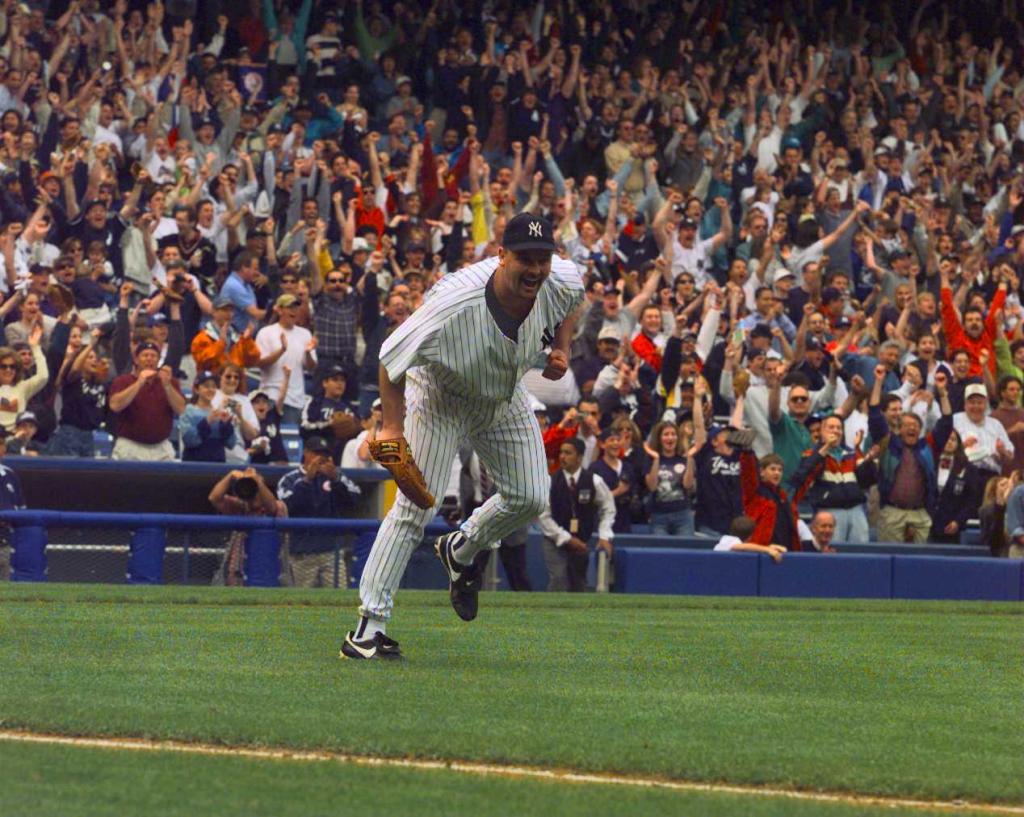

On the second pitch, Meares lifted a lazy fly ball down the right field line. Wells turned to watch the flight of the ball, backpedaling off the mound and starting to smile as he waited for Paul O’Neill to catch it. When O’Neill snared it at 4:16 p.m., Wells pumped his fist twice and was engulfed by his teammates. The warmest hug was shared with Posada, his copilot to perfection and his favorite catcher.

“They threw a lot of righty batters against David and he pitched well against righties because he had a great cutter,” Posada said. “It made his fastball even better. And his curveball was just unbelievable that day. He was snapping it off and he had great control with it and they weren’t recognizing it. His curve was probably the reason why he threw a perfect game.”

It had been a topsy-turvy ride for Wells. He went from nearly blowing a 9–0 lead and arguing with his manager to doing something extraordinary. What is the moral to Wells’s story about going from being so hungover that his skull rattled to being absolutely perfect?

“It was a stupid thing to do,” Wells said. “I just got lucky. That’s the only way to look at it. It was pure luck and then getting locked in. My bullpen was so bad and my first pitch of the game was right down the middle at 93 or 94. I was like, ‘Wow, where did that come from?’ I kind of keyed off that. I just threw to the glove.”

He paused and added, “Well, what I could see of the glove.”

Whether there was a cause and effect between Torre criticizing Wells and Wells getting angry and Cone getting involved, we will never know. But there had to be some connection between those events. Even if Torre’s criticism emboldened Wells to simply prove his manager wrong, he was a much more competitive pitcher on a day where he felt queasy and it would have been easy for him to fade. He didn’t. He fought. For one afternoon, he was perfect.

Excerpted from “1998 Yankees: The Inside Story of the Greatest Baseball Team Ever” by Jack Curry and reprinted by permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.