Inside the grim reality of the fentanyl plague that runs rampant in NYC and has killed celebs

Inside a hip Lower East Side cocktail bar, late on a recent Saturday night a crowd of young party-goers formed a line outside the bathroom as punk music blared in the background.

That’s when one local restaurant worker cut through the noise with a warning: “If anyone is using drugs tonight, do it safely and test!”

This has become the unsettling new reality both in and out of the party scene in New York City as fentanyl, the synthetic opioid responsible for about 150 overdose deaths in the US a day, has infiltrated nearly every aspect of the illicit drug market — leaving unsuspecting users and their families reeling.

“I am surprised that more people aren’t aware that fentanyl is definitely filtering into the cocaine supply,” New York City Special Narcotics Prosecutor Bridget Brennan said in an interview.

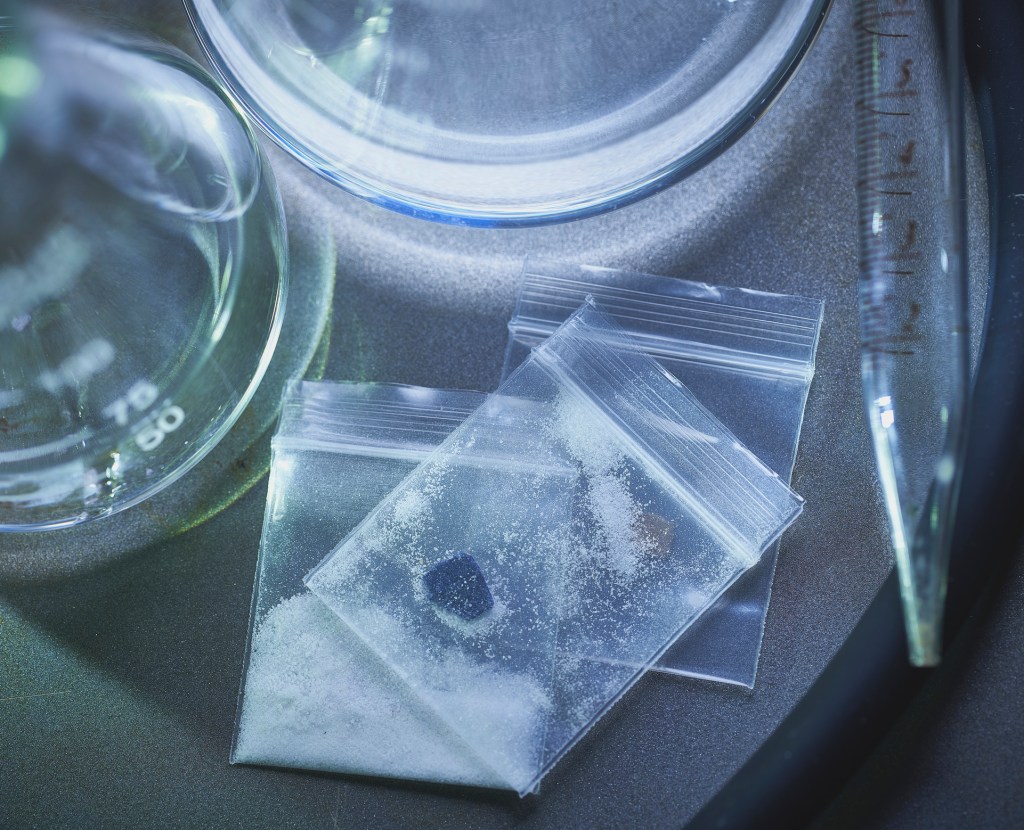

The cheap lab-made drug is often cut into other illicit substances due to its potency, getting mixed in with heroin, methamphetamine, and even cocaine. It’s also pressed into pills made to look like other pharmaceutical opioids or benzodiazepines.

The epidemic is creating suffering that cuts through all demographics, killing people on the streets, the middle class and the rich and famous alike — such as Leandro De Niro Rodriguez, the grandson of famed actor Robert De Niro who was found dead of an overdose at 19 earlier this month from suspected fentanyl-laced drugs allegedly sold to him by a 20-year-old dealer known as the “Percocet Princess.”

“People will say ‘Don’t worry I got it from my guy.’ But anyone can die from bad drugs,” said Darryl Phillips, 48, the founder of a non-profit that distributes fentanyl-testing strips.

“Demi Lovato, Lil Peep, Mac Miller. They paid top dollar and they weren’t any safer.”

Rapper Lil Peep, a friend of Post Malone, died in 2017 from taking Xanax laced with fentanyl. The next year Miller, another rapper, died from a fatal dose of fentanyl in cocaine. Lovato almost died the same year from a similar cocktail.

Law enforcement and public health officials have been warning about fentanyl for years. But the number of fatal overdoses linked to the lethal opioid continues to hit record levels.

The US saw 102,429 drug deaths last year — with the vast majority having fentanyl to blame.

Young people, especially, have been on the receiving end of the suffering, with the rate of teen drug overdose deaths nearly doubling between 2019 and 2020, and spiking another 20% in 2021, according to recent research.

Fueling the flood of tainted drugs are the kids of notorious Mexican kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who have taken the reins of his murderous Sinaloa Cartel, along with the so-called new generation Jalisco Cartel, which has hundreds of members brazenly operating in the US.

The cartels have turned the drug trade into a game of policing whack-a-mole, with their use of social media, encrypted texting apps and cheap technology creating new challenges for law enforcement attempting to disrupt the flow.

But for people like Phillips, the latest phase of the war on drugs isn’t about making quick gains — he is just tired of watching his friends die.

How fentanyl came to flood the supply:

Fentanyl has become a favorite of the cartels as a cheap, deadly alternative cutting agent to boost the potency of their drugs and increase profits.

Interviews with federal and local law enforcement officials along with a review of public testimony and reports from the US Drug Enforcement Administration reveal just how the trade evolved, bringing the deadly drug into the hands of everyday users and partygoers in the US.

Fentanyl — a quick-acting analgesic and anesthetic 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine — started to emerge in the drug market back in 2013.

Within two years, the DEA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had issued a rare, nationwide alert that fentanyl posed a “significant threat to public health and safety” as the synthetic opioid contributed to an “alarming rate” of drug deaths.

The cartels first began by buying wholesale fentanyl with varying levels of potency and mixing the drug in labs, allowing them to stretch one kilo of other drugs into more than a dozen.

In the years that followed, the Sinaloa crew — the main drug supplier of the New York area — and the New Generation Jalisco, aka Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación or CJNG, learned to make their own fentanyl by buying chemicals from China and India, and started smuggling powder and pressed pills into the US.

The cartels realized the ease of making fentanyl was much more cost-effective as part of their criminal enterprise than producing heroin, which needs to be grown, harvested and then processed.

Kilos of fentanyl go for roughly $6,000 south of the border but by the time they reach New York City, they fetch anywhere between $30,000 to $35,000. A fentanyl pill can be made in Mexico for about 10 cents, and sell in the Big Apple for anywhere between $10 and $30.

“The cartel is taking advantage… they’re using our addiction, they’re using the substance use dependent disorder problem here in the United States to make more money,” said Frank Tarentino, the DEA’s Special Agent in Charge of the agency’s New York division.

“The more people they can addict, the more people they can get to buy their product, the more money they’re going to make.”

When the feds sounded the alarm in 2014, 3,334 of drug cases — meaning any substance seized and sent to a lab, including for being involved in an overdose — came back positive for fentanyl. By 2021, that number had soared to 153,949.

A large part of that uptick, according to officials, is tied to the influx of the synthetic in party drugs with nearly every street pill and cocaine containing some trace of fentanyl.

“It’s catastrophic. It’s unprecedented,” said Tarentino. “We’ve never seen devastation like this ever in our country as it relates to illicit drugs.”

From Mexico to NYC: tracking the flow of fentanyl

The trafficking of fentanyl over the last decade has become much “more diverse” as the Mexican cartels streamlined their process — and found new ways of shipping the illicit drug across the US.

The shipments start off in Sinaloa, a Mexican state in the northwest part of the country, and are transported to Tijuana, just south of the California border, where smugglers prepare the packages, sometimes tucking them in hidden compartments or stashed in crates of fruits or vegetables.

Once in the US, the shipments can make their way into the city either via exchanges at truck stops in New Jersey or by being driven directly to a local distributor, often situated in the Bronx. Cars with out-of-state plates have also increasingly been bringing kilos of fentanyl — in powder or pill form — into the city.

“They’re generally from the West Coast, usually California. And then they appear to be traveling over land and bringing those loads into the city,” said Brennan, the NYC special narcotics prosecutor.

Another cartel tactic once shipments are in the US is to move them from San Diego to stash houses in LA. From there, smugglers pack in a handful of kilos with large household items — ceiling fans, for instance — and mail them across the country to locations in New York City.

Once the package gets to NYC, a low-level cartel member retrieves it before doling it out to local distributors.

“We know, for absolute certainty, that the Sinaloa Cartel is sending members into this region to transport large quantities of drugs,” Tarentino said in a recent interview, estimating about 250 Sinaloa Cartel members are currently operating in America.

The shipping process has provided challenging for the feds, said the special agent, who stopped short of calling it a blind spot for the feds.

“It’s hard to identify packages unless you have some inside information where you may have a tip or a lead or some prior knowledge of this package being shipped,” Tarentino said.

“Otherwise, they could shotgun 100 packages out of Mexico or 100 packages out of wherever, and maybe 98 get through and two get seized,” he added. “It’s very cost-effective.”

The cartels have also weaponized simple tech to encrypt conversations — which has created a “big problem” for the feds to get leads on new shipments. In some cases, the smugglers also equip parcels with listening devices to monitor if the packages have fallen into law enforcement’s hands.

“Drug trafficking is really just limited by the traffickers’ imagination,” he said.

A personal epidemic

Phillips, the founder of the A$AP Foundation, has his own personal battle with the cartels that is taking place daily as he takes on a new approach to stop the epidemic of fentanyl-linked deaths.

“I’m not saying don’t do drugs,” Phillips, 46, recently told The Post. “That’s not going to work. If anyone is using, try to be safe. Test it.”

As The Post joined Phillips on LES while he re-filled fentanyl testing strip boxes at more than a half dozen participating businesses around Orchard Street — including the one where bargoers were warned to test their drugs — he was greeted with a warm welcome at each stop.

“Better to have people testing drugs in your bathroom than overdosing in there,” Phillips said.

The high-end street clothing store, 375 Showroom — where The Post had to be buzzed in and was greeted by a towering guard — was the first spot where Phillips put out the testing strips back in 2019.

“Almost everyone in these spots knows someone who’s passed away,” said one of the store’s managers, Evan, as he displayed about a dozen sweatshirts for an incoming customer expecting to drop a few grand on clothes.

The other businesses in Phillips’ diverse network in the area include an often-Instagrammed bar, a posh high-end women’s clothing store, art galleries and a Mexican restaurant featured in The New York Times.

“I love that we have the kits here,” Christian, a worker at Scarr’s Pizza on Orchard Street said as Phillips refilled the clear shoebox-sized bin with a few dozen tests.

“My friend just OD-ed on Saturday,” he said from behind the counter.

“Did he survive?” Phillips asked.

“Nah… he died.”