One of the central tenets of the Biden administration’s energy policy is the pursuit of “green” hydrogen, defined as hydrogen manufactured with zero carbon emissions.

This push has involved $7 billion dollars in subsidies for the creation of Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs as well as significant tax breaks for hydrogen production through the Inflation Reduction Act.

While the administration touts this as beneficial, the reality is that using hydrogen as an energy source makes no economic sense.

There are two reasons this scheme won’t work.

First, we cannot create usable energy out of thin air. Instead, we expend energy to obtain energy resources — drilling for oil and gas, mining coal — to convert it to forms we can use for things like generating electricity or powering your car.

This works because the conversion process uses much less energy than those resources provide.

We would never refine crude oil into gasoline if two gallons’ worth of energy were required to produce every gallon.

But that’s precisely the problem with green hydrogen, which must be manufactured.

Manufacturing leads to the second problem because no manufacturing process is 100% efficient; some energy is always lost, just as some of the heat from a furnace escapes up the chimney.

Consequently, it will always take more energy to manufacture hydrogen than that hydrogen contains.

In fact, as I show in my new Manhattan Institute report, manufacturing hydrogen requires at least twice as much energy as the hydrogen itself can provide, even before accounting for the energy lost when that hydrogen is subsequently used, such as in a fuel cell or burned in an industrial furnace.

That’s a thermodynamic fact, which no subsidy can change.

The Biden administration has chosen to invest billions of taxpayer dollars into manufacturing hydrogen via electrolysis.

Why?

Because electrolysis, which involves running an electric current through water to break apart hydrogen and oxygen molecules, yields zero carbon emissions.

This “green” end, it seems, justifies even economically absurd means.

As part of its green hydrogen efforts the administration launched an “Earthshot” program, which aims to reduce the cost of manufacturing green hydrogen through electrolysis by 80% by 2030 to just $1/kg.

The administration envisions using “surplus” wind and solar electricity – never defining what that means – in manufacturing plants that will produce millions of tons of zero-carbon hydrogen, which can then be used in industrial processes like steel and cement manufacturing, and thus move the country toward its net zero goal by 2050.

The problem here is that wind and solar power are inherently intermittent – the wind doesn’t always blow, and the sun doesn’t always shine.

Hence, operating a manufacturing plant only when there happens to be excess wind and solar generation would be neither practical nor cost-effective.

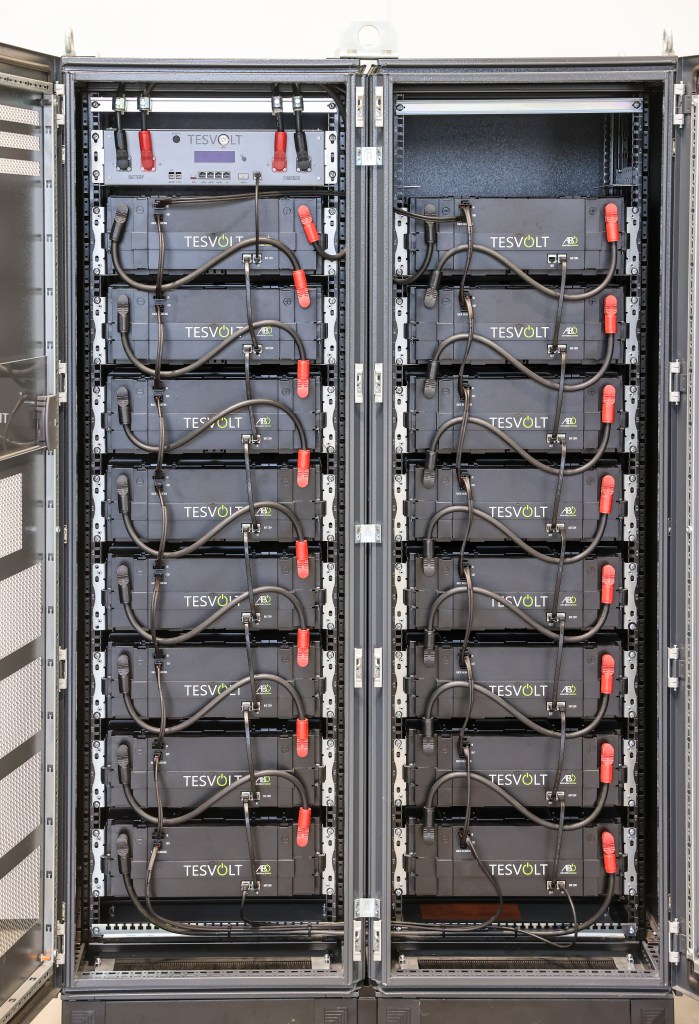

As for storing surplus wind and solar electricity in batteries and enabling plants to operate on a consistent schedule, my report shows the costs of the necessary storage alone could be as large as the cost of the manufacturing plants themselves, even if battery costs were cut in half.

No matter what process is used, Earthshot’s goal of manufacturing green hydrogen at a cost of no more than $1/kg is unrealistic.

The costs to build and maintain electrolysis plants, generate and transmit the electricity those plants require, and compress and store the hydrogen so it could be transported will far exceed $1/kg, even if electrolysis plant costs fall by 80%.

The tragedy in all of this is that the administration’s green hydrogen production goal — 10 million metric tons annually by 2030—would have no measurable impact on climate, even if it were achievable.

The resulting carbon reductions would be equivalent to two days of U.S. emissions in 2022 and less than six hours of world emissions.

Rather than showering taxpayer money on another energy boondoggle, this administration, and subsequent ones, should focus on streamlining the process for licensing new nuclear plants — especially, small, modular ones — and investing in research and development efforts to reduce the cost of those plants.

As for hydrogen, its best use will continue to be as a feedstock for refining crude oil and manufacturing ammonia used in fertiliser.

Jonathan Lesser is the president of Continental Economics and an adjunct fellow with the Manhattan Institute.