On April 29, 1974, President Richard Nixon delivered a primetime televised address that marked a decisive moment in Watergate — and, in ways no one could appreciate at the time, a turning point for civilization.

“We live in a time of very great challenge and great opportunity,” the president said. It was the Cold War: when two nuclear-armed superpowers, America and the Soviet Union, an expansionist Stalinist empire, vied for hegemony.

But a steady stream of revelations from the Watergate scandal, arising from a break-in and wiretapping at Democratic National Committee headquarters staged by employees of Nixon’s re-election campaign, had gripped the nation for two years.

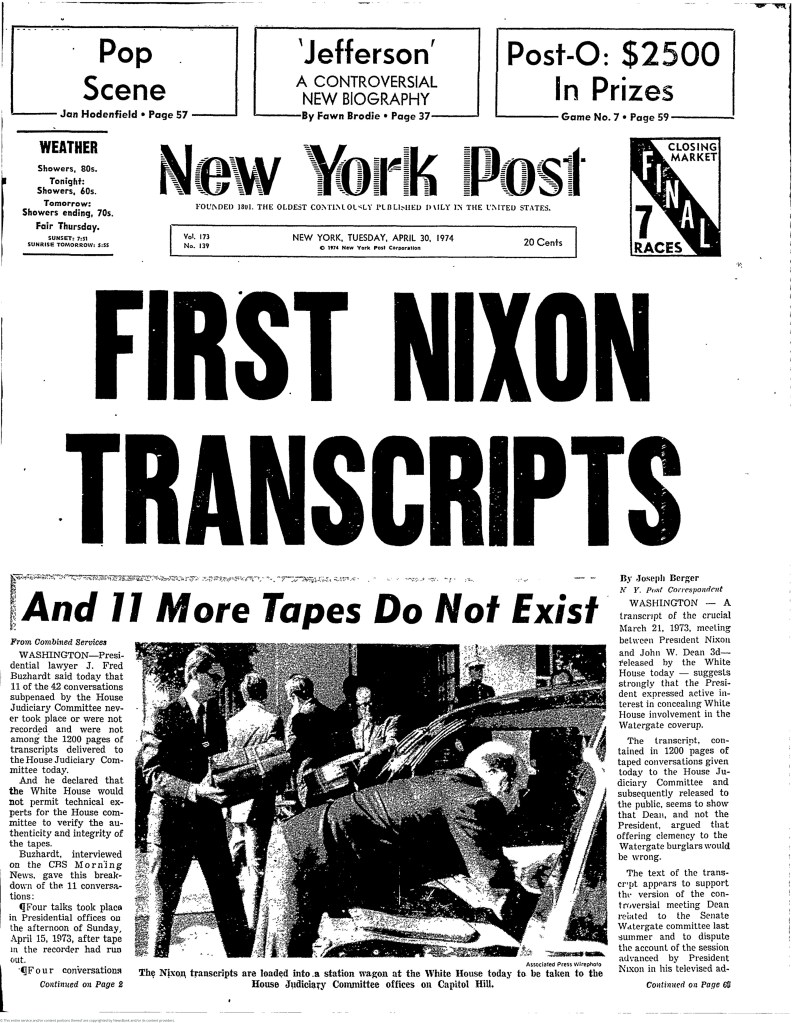

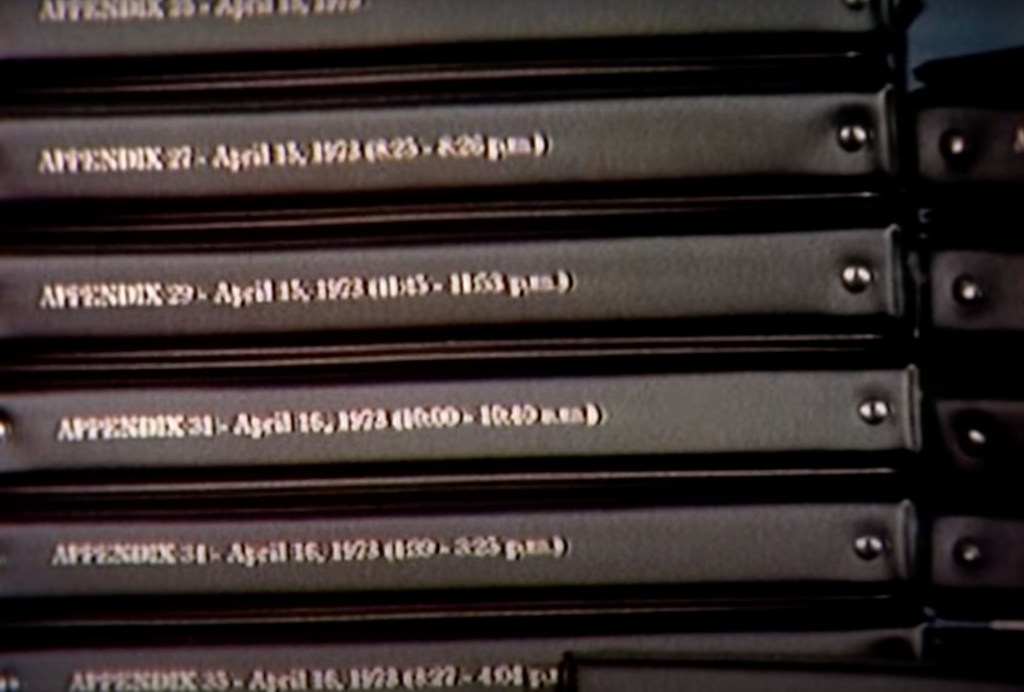

And now, as the president spoke, all anyone wanted to know was: What’s in the binders?

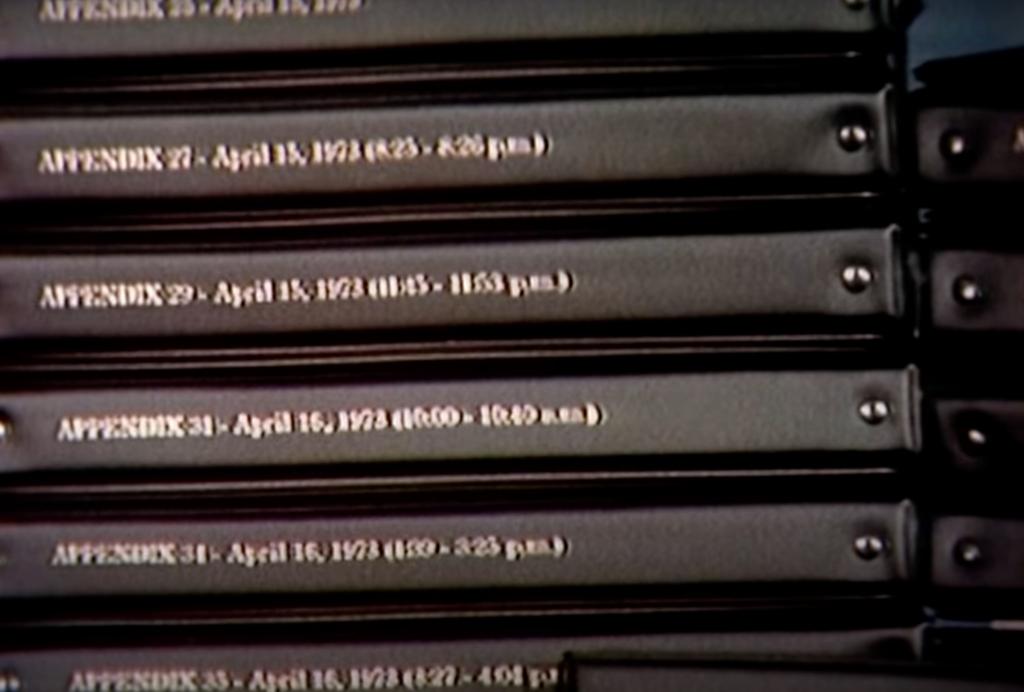

The camera had widened out to reveal, left of Nixon’s elbow, two stacks of black binders adorned, in embossed gold, with stately lettering and the presidential seal.

“In these folders that you see over here,” Nixon explained, “are more than 1,200 pages of transcripts of private conversations I participated in between September 15, 1972 and April 27 of 1973 with my principal aides and associates with regard to Watergate.”

The Watergate tapes — public at last!

Their existence had surfaced in July 1973, when Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield disclosed in televised hearings before the Senate Watergate committee that, starting in early 1971, the president had secretly recorded himself for more than two years.

So poorly managed was the taping system that it was two days after Butterfield delivered his bombshell before the Sony TC-800B recorders were paused and dismantled.

Every president since Franklin Roosevelt had recorded some conversations.

But as technology improved, the practice, like an errant machine, accelerated: John F. Kennedy generated 260 hours of tapes, Lyndon Johnson, 800 hours.

Operated by the Secret Service, Nixon’s system was the most ambitious.

In a 90-day period from February to May 1971, two dozen microphones were installed in Nixon’s Oval Office desk; the wall lamps over the Oval Office fireplace; the Oval Office telephone; the Cabinet Room; the Lincoln Sitting Room telephone; Nixon’s “hideaway” office in the Old Executive Office Building; and the presidential office, and telephones, at Aspen Lodge at Camp David.

With the exception of the Cabinet Room, all the microphones were voice-activated.

This meant that Nixon himself could not stop or pause the recording process, a feature designed to compensate for the president’s clumsiness, well known among subordinates, with mechanical devices.

The Nixon administration thus became the best-documented regime in human history: 3,700 hours of the world’s most powerful leader, captured on the job in real time, on 950 reels of magnetic tape, poorly labeled and haphazardly stored in an unmarked half-closet underneath a staircase in the Executive Office Building.

The junior staffer entrusted with the key took to calling the space, with suitable Cold War menace, “Safe-Zone 128.”

In the 1984 book “Secret Agenda,” author Jim Hougan cited the previously unreported account of William McMahon, a former officer of both the Central Intelligence Agency and the Secret Service who worked in the Nixon White House.

McMahon disclosed that CIA regularly “detailed” employees from the agency’s Office of Security to the Secret Service division that maintained the taping system.

This revelation suggests, as Hougan noted, that the CIA had enjoyed “unrivaled access to the president’s private conversations and thoughts.”

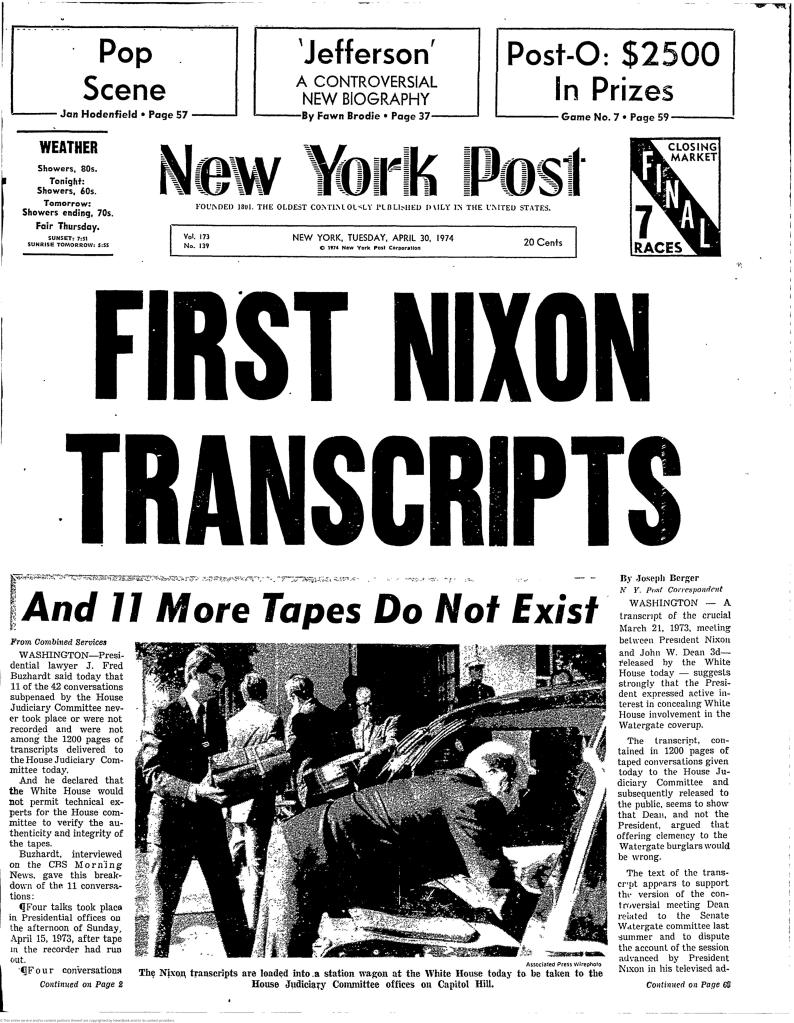

In his April 29 speech, Nixon said the binders were being delivered to the House Judiciary Committee, which was examining impeachment and had subpoenaed 42 Watergate-related conversations. Attached to the submission was a legal brief in the president’s defense.

Compounding Nixon’s troubles was the disclosure, in November 1973, that the tapes contained a gap: five to nine deliberate erasures that obliterated, with buzzing noises, 18 and a half minutes of an Oval Office conversation recorded on June 20, 1972: three days after the Watergate arrests.

Contemporaneous notes showed the discussion focused on the public relations implications of the Watergate arrests; but the gap’s mere existence worsened the president’s standing.

Hours after the April 29 speech, the Judiciary Committee voted to declare that the president had “failed to comply” with its subpoena.

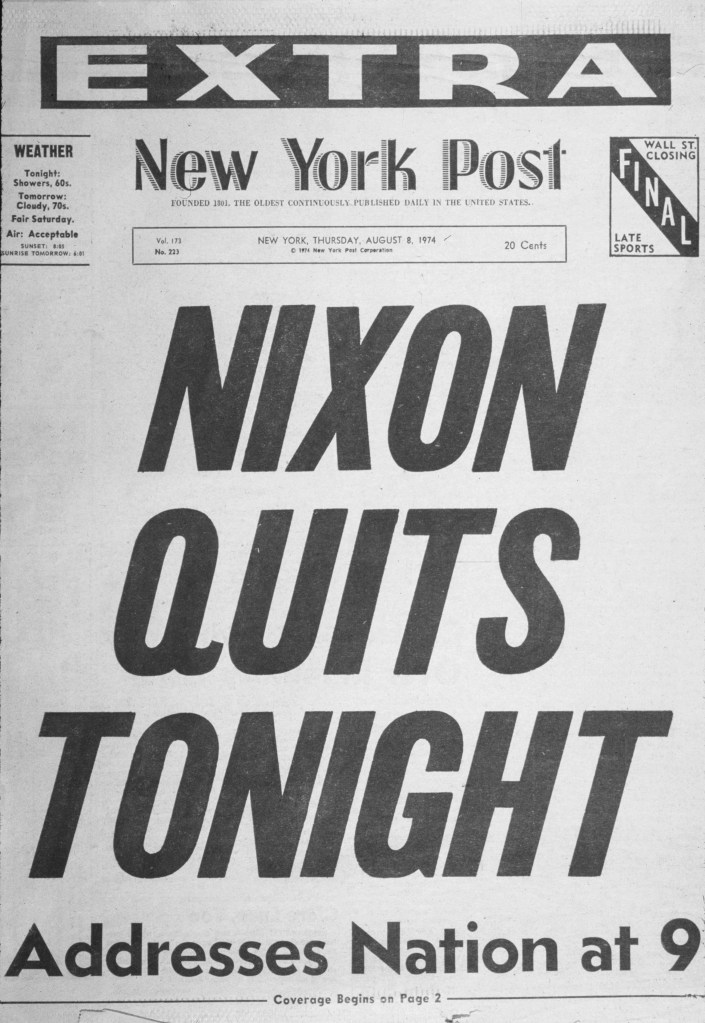

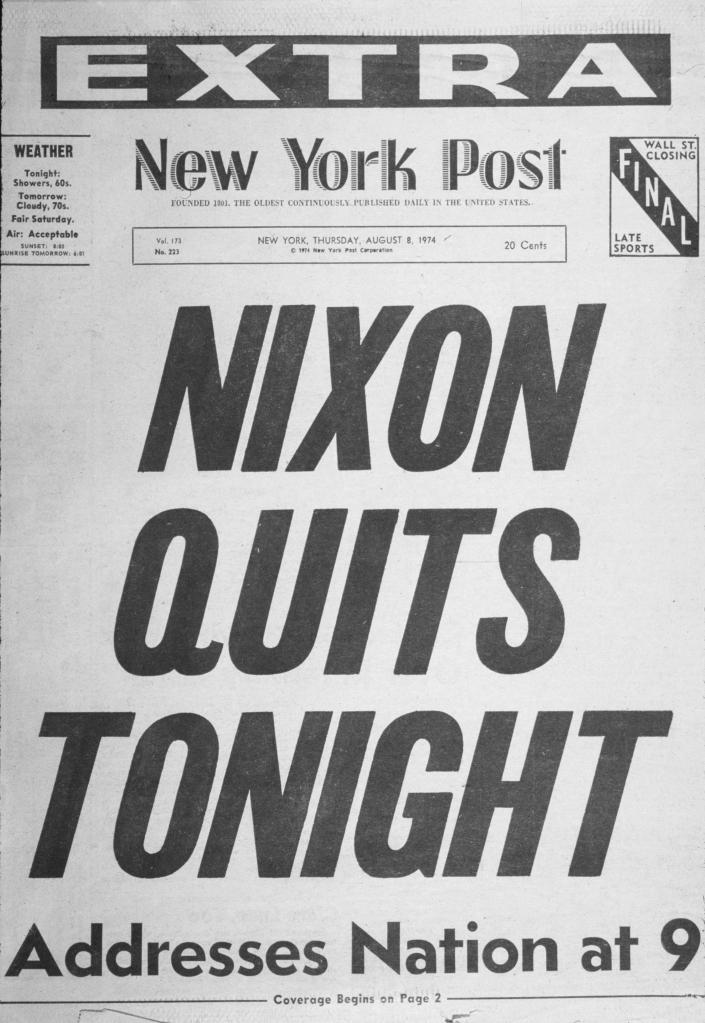

Litigation ensued. In July, the Supreme Court ruled 8-0 that the demands of a criminal investigation outweighed Nixon’s claims of “executive privilege.”

The tapes — not just transcripts — must be produced.

When they were, on Aug. 5, they included the “smoking gun.” Recorded on June 23, 1972, the Oval Office tape captured Nixon acquiescing in a plan to enlist the CIA director to pressure the FBI into shutting down its investigation.

The outcry was overwhelming. Nixon resigned on Aug. 8.

Gesturing at the binders on live television, Nixon said that in addition to going to the Judiciary Committee, they would also be released to the public.

No leader in world history had ever allowed so vast and intimate a record of his day-to-day decision-making to be released to those he governed.

Only “clearing the air,” Nixon declared, would “allow this matter to be brought to a prompt conclusion.”

It was: He resigned 101 days later.

In addition to the revelations of abuse of power, the country was stunned by the casual profanity of the Quaker president, scarcely concealed by the recurring phrase “[expletive deleted].”

This was the coinage, along with the term “smoking gun,” of a young White House lawyer, Geoff Shepard, who oversaw the preparation of the binders.

“We have seen the private man,” editorialized the Chicago Tribune, “and we are appalled.”

The Omaha World-Herald, which had endorsed Nixon in three presidential campaigns, demanded he resign.

“Our leader should be setting a good example,” lamented CBS News’ Dan Rather.

Others demurred.

“I have known five presidents,” said Reverend Billy Graham, “and I suspect if we had the transcriptions of their conversations, they, too, would contain salty language.”

“A real man knows how to swear,” novelist Norman Mailer told The New Yorker.

To him Nixon came off as “the good, tough, even-minded, cool-tempered, and tastefully foulmouthed president of a huge corporation.”

Comedians recorded satirical albums.

But the damage was real—and lasting.

Writer Michael Novak assessed that the tapes had “weakened the symbolic power of the presidency…central to civil religion.”

William Rehnquist, who served under President Nixon when appointed to the Supreme Court — the reason Rehnquist did not participate in the 8-0 ruling — told me in a 1993 interview, in chambers as chief justice, that Nixon, eager to “sound tough,” spoke as he imagined the Kennedys had.

After Nixon resigned, Congress voted, effectively, to seize the tapes for the National Archives.

Clips were played at three trials in the 1970s, but not until 1988 were the first audio segments, processed by federal archivists, publicly released.

Supported by a 27,000-page “finding aid,” the release of “new” tapes continued for decades.

In 2000, this reporter became the first private citizen to listen to the most sensitive tapes of all: from December 1971, when Nixon learned, in a nighttime Oval Office session, that the Joint Chiefs had systematically spied on him and national security advisor Henry Kissinger, stealing 5,000 classified documents—in wartime.

Attorney General John Mitchell could be heard calmly dissuading Nixon from pressing espionage charges.

The April 29 speech, and the court’s ruling, changed everything.

Public figures were served notice: Your private musings will come out.

The mind reels at how many public figures have ignored the lesson.

A further irony is that the precise contents of the tapes — fatal to Nixon, their release a watershed — have never been agreed upon.

The non-telephone recordings were so muddy that H.R. Haldeman, the chief of staff who supervised Butterfield, later wrote that “there can be no such thing as a completely accurate transcript” of them.

The Judiciary Committee and prosecutors released their own transcriptions.

Newspapers rushed out glossy paperbacks. Worst was “The Nixon Defense” (2014), a volume of “new” transcriptions edited by John Dean, the central Watergate conspirator whose defection, and false testimony, helped seal the fate of Nixon and his men.

Dean’s volume used omission, distortion, summaries, and other sleights of hand to minimize, yet again, his own culpability in the scandal.

Ultimately, abuse of power segments make up only about 5% of the tapes’ total content.

“The most significant revelation of the Nixon tapes is that they capture what it is like to be president,” historian Luke Nichter, the co-editor, with Douglas Brinkley, of two volumes of Nixon tape transcripts, told me recently. “A president spends most of his time reacting to problems.”

Some 500 hours remain withheld; of the rest, now public, only 10% have been transcribed.

In many respects, these extraordinary documents remain a mystery.

“We learn a lot on the Nixon tapes about what others thought, but not always what Nixon thought,” Nichter says. “They are a story with a middle, but not often a beginning or an end.”

_________

James Rosen is a White House correspondent for Newsmax and the author, among other books, of “The Strong Man: John Mitchell and the Secrets of Watergate.”