The Daily Worker

In the 1929 General Election the Labour Party obtained 8,370,417 votes and won 287 seats, enabling Ramsay MacDonald to form a minority government. The Communist Party of Great Britain only received 47,544 votes and its membership had fallen to 3,500. It seemed to have lost the fight to gain the support of the British working-class. Harry Pollitt, the general secretary, realised the CPGB had serious problems and he admitted that "the transmission belts were turning no wheels" and that "the bridge to the masses has become only the same faithful few going over in every case". (1)

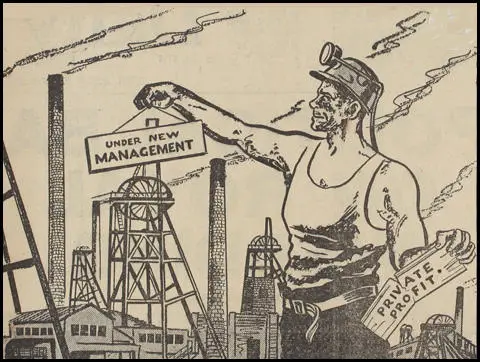

Pollitt recruited Tom Wintringham to help establish a new CPGB newspaper. Wintringham found premises at 41 Tabernacle Street, London EC2. On 1st January 1930, launched The Daily Worker. Wintringham later commented: "So we got it out on time with antiquated machinery, makeshift organisation, candles lighting the grim warehouse that was our office, the newspaper trains closed to us." (2)

William Rust became the first editor of the newspaper. Rust was described by a colleague at this time as "round and pink and cold as ice." Another friend said that he rarely saw him smile. His biographer, Kevin Morgan, pointed out that he was chosen because it was claimed that "even among his fellow communists for his quite exceptional devotion to Moscow." (3)

Rust made it clear from the beginning that the newspaper was going to be an organ of agitation. "There was little news in the Daily Worker in the early days, unless you wanted to read very politically slanted articles about unemployment, strikes and the Soviet Union, or absurd sectarian propaganda". (4) Lenin was quoted in the first edition as saying: "without a political organ, a movement deserving to be called a political movement is impossible in modern Europe." (5) On 25th January 1930, Rajani Palme Dutt, wrote an article in the newspaper condemning the inclusion of sports news: "Capitalist sport is subordinate to bourgeois politics, run under bourgeois patronage and breathing the spirit of patriotism and class unity; and often of militarism, fascism and strike breaking. Sport is a hotbed of propaganda and recruiting for the enemy. Spectator sports (horse racing and football) are profit run professional spectacles thick with corruption. They are dope; to distract the workers from the bad conditions of their lives, to stop thinking, to make passive wage slaves. You cannot reconcile revolutionary politics with capitalist sport!" (6) It was decided to stop covering sport. This was unpopular and Wintringham later recalled: "I had to pay printers with I.O.U.s, stave off landlord and business, keep the paper going in spite of a mountain of debts for paper and machinery." After only a few weeks the circulation had dropped from 45,000 to 39,000 and the newspaper was losing £500 a week. Pollitt wrote to John Ross Campbell in Moscow and told him about "a financial problem that I do not know how to face". Eventually it was arranged for the Soviet Union to fund the venture. However, "Pollitt knew that the money he got to run the Daily Worker depended on Moscow's approval of its contents." (7) Claud Cockburn was an investigative journalist who published his work in The Week. Cockburn was persuaded to contribute to the Daily Worker(using the name Frank Pitcairn). As he explained in his autobiography, In Time of Trouble (1957): "It was at about this time (September 1934) that Mr Pollitt, Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, whom I had never met, was suddenly announced on the telephone - would I, he asked, take the next train, in twenty minutes or half an hour, and report a mine disaster at Gresford, North Wales. Why? Because he had a feeling that there was a lot more in it than met the eye. But why I in particular? Well, because, it seemed, Mr Pollitt - who was worrying at the time about what he believed to be a lack of' reader appeal' in the Daily Worker - had been reading The Week and thought I might do a good job." (8) Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, asked him to cover the Spanish Civil War for the Daily Worker. When he arrived in Spain he joined the Fifth Regiment so that he could report the war as an ordinary soldier. While in Spain he published Reporter in Spain. Cockburn was attacked by George Orwell in his book Homage to Catalonia. In the book he accused Cockburn of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Orwell was particularly critical of the way Cockburn reported the May Riots in Barcelona. (9) In 1935 Idris Cox became editor of the newspaper. The hardline Rajani Palme Dutt, replaced him a year later. John Ross Campbell was the foreign correspondent of the Daily Worker in the Soviet Union and became a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky. As Campbell was the CPGB representative in the Soviet Union, it is unlikely that he was unaware of what was really going on. (10) Along with Palme Dutt and Denis Nowell Pritt, Campbell were "enthusiastic apologists for the Moscow frame-up trials". (11) In 1936, Victor Gollancz, formed the Left Book Club. It had over 45,000 and 730 local discussion groups, and it estimated that these were attended by an average total of 12,000 people every fortnight. The Left Book Club published several books written by members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This included the defence of the Soviet Show Trials. This included the "suppression of some of his (Gollancz) most fundamental instincts and cherished beliefs" and included his "ready acceptance of Stalinist propaganda concerning the Moscow trials, despite the disquiet widely evident among socialists". (12) Gollancz was vice-president of the National Committee for the Abolition of the Death Penalty but he agreed to Pollitt's suggestion that he published a defence of the prosecution and execution of former members of the Soviet government. Dudley Collard was approached to write a book on the legality of the Soviet Show Trials. The book was entitled Soviet Justice and the Trial of Radek and Others. (13) An article by John Ross Campbell in the Daily Worker on 5th March 1938: "Every weak, corrupt or ambitious enemy of socialism within the Soviet Union has been hired to do dirty, evil work. In the forefront of all the wrecking, sabotage and assassination is Fascist agent Trotsky. But the defences of the Soviet Union are strong. The nest of wreckers and spies has been exposed before the world and brought before the judgement of the Soviet Court. We know that Soviet justice will be fearlessly administered to those who have been guilty of unspeakable crimes against Soviet people. We express full confidence in our Brother Party." (14) Dave Springhall replaced Rajani Palme Dutt as editor of the Daily Worker in 1938. Springhall was not an experienced journalist and John Ross Campbell became editor in 1939. Later that year the Left Book Club published Campbell's Soviet Policy and its Critics, in defence of the Great Purge in the Soviet Union. He agreed with Dudley Collard that the main issue between Trotsky and Stalin was over the issue of "socialism in one country". He quoted Stalin as saying: "Our Soviet society has already, in the main, succeeded in achieving Socialism... It has created a socialist system; i.e., it has brought about what Marxists in other words call the first, or lower phase of Communism. Hence, in the main, we have already achieved the first phase of Communism, Socialism." (15) It was later argued that Campbell had good reason to be uncritical of the Soviet government. He married Sarah Marie Carlin in 1920. He acted as father to five children from a previous marriage. Sarah encouraged her oldest son, William, to go to the Soviet Union and help build socialism. According to Francis Beckett, the author of Stalin's British Victims (2004), "with his stepson as a sort of hostage in the Soviet Union" he was not in a position to tell the truth of the way that loyal Bolsheviks were being persecuted. (16) The rise of fascism in Germany and Italy increased support for the Communist Party and after the signing of the Munich Agreement, membership reached 15,570. Members included Mary Valentine Ackland, Felicia Browne, Christopher Caudwell, James Friell, Claude Cockburn, John Cornford, Patience Darton, Len Crome, Ralph Fox, Nan Green, Charlotte Haldane, John Haldane, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawn, Lou Kenton, David Marshall, Jessica Mitford, A. L. Morton, Esmond Romilly, George Rudé, Raphael Samuel, Alfred Sherman, Thora Silverthorne and E. P. Thompson. On 23rd August, 1939, Joseph Stalin signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler. However, long-time loyalist, John Ross Campbell, felt he could no longer support this policy. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said." Other leaders of the CPGB agreed with Campbell a statement was issued that "declared its support of all measures necessary to secure the victory of democracy over fascism". (17) On the outbreak of the Second World War, the General Secretary of the CPGB, Harry Pollitt, published a 32-page pamphlet, How to Win the War (1939): "The Communist Party supports the war, believing it to be a just war. To stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary-sounding phrases while the fascist beasts ride roughshod over Europe, would be a betrayal of everything our forebears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism.... The prosecution of this war necessitates a struggle on two fronts. First to secure the military victory over fascism, and second, to achieve this, the political victory over the enemies of democracy in Britain." (18) On 24th September, Dave Springhall, a CPGB member who had been working in Moscow, returned with the information that the Communist International characterised the war as an "out and out imperialist war to which the working class in no country could give any support". He added that "Germany aimed at European and world domination. Britain at preserving her imperialist interests and European domination against her chief rival, Germany." (19) At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff." William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten." Harry Pollitt then made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership." (20) However, when the vote was taken, only John Ross Campbell, Harry Pollitt, and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Rajani Palme Dutt and William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Pollitt, then agreed to disguise this conflict and issued a statement saying it was "nonsense and wishful thinking the attempts in the press to create the impression of a crisis in the Party". (21) Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures. Palme Dutt also published a new pamphlet, Why This War? explaining the new policy of the CPGB. Campbell and Pollitt were both removed from the Politburo. (22) Campbell also "subsequently rationalized the Comintern's position and publicly confessed to error in having opposed it." (23) Douglas Hyde claims that Palme Dutt was clearly the "most powerful man in the Party". (24) On 22nd June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union. That night Winston Churchill said: "We shall give whatever help we can to Russia." The CPGB immediately announced full support for the war and brought back Harry Pollitt as general secretary. As Jim Higgins has pointed out Palme Dutt's attitude towards the war was "immediately transformed into an anti-fascist crusade." (25) In the early stages of the Second World War, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, banned the Daily Worker. Following the German army's invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941, a campaign supported by Professor John Haldane and Hewlett Johnson, the Dean of Canterbury, began to allow the newspaper to be published. On 26th May 1942, after a heated debate, the Labour Party carried a resolution declaring the Government must lift the ban on the newspaper. The ban was lifted in August 1942. (26) As Francis Beckett has pointed out: "Suddenly the Communist Party was popular and respectable, because Stalin's Russia was popular and respectable, and because at a time of war, Communists were able to wave the Union Jack with the best of them. Party leaders appeared on platforms with the great and the good. Membership soared: from 15,570 in 1938 to 56,000 in 1942." (27) Officially, William Rust, the editor of The Daily Worker, remained in charge, however, Douglas Hyde, the news editor, later recalled: "We would sit in a room, just half a dozen of us, and talk about the political issues of the day." However, it was Rajani Palme Dutt who decided on the newspaper's policy. "When we had all had our say, Dutt would drape his arm over the arm of his chair - he had the longest arms I have ever seen - bang his pipe out on the sole of his shoe, and sum up. Often the summing up was entirely different from the conclusions we were all reaching, but no one ever argued." (28) Rust attempted to turn the Daily Worker into a popular mass paper. According to Francis Beckett: "He was a fine editor: a cynical boss who thumped the table in his furious rages, he nonetheless inspired journalists' best work. A tall and by now heavily built man, Rust was one of the Party's most able people, and one of the least likeable." Sales of the newspaper reached 120,000 in 1948. (29) Alison Macleod worked for the newspaper after the war. In her book, The Death of Uncle Joe (1997), she claimed that in private John Ross Campbell, the assistant editor, was highly critical of the actions of Joseph Stalin. He agreed with Tito in his dispute in June 1948 but in his articles he "refused to say that the Soviet Government was right, stopped short of making any public protest". Campbell argued that if you "were serious about wanting Socialism or you weren't. If you were serious, you couldn't attack the one country which had achieved it." (30) William Rust, aged 46, died of a massive heart-attack on 3rd February 1949. John Ross Campbell once again became the editor of the Daily Worker. (31) According to one source he was an excellent journalist: "Johnny Campbell, who took over as editor after Rust's death in 1949, was in the great Scottish Communist tradition of worker intellectuals, a man". (32) Campbell was liked and respected by his staff. One of his young sub-editors wrote: "Since then I have met several editors who put on matey airs. They imagine (as they lunch at the Savoy Grill) that the reporters lunching at the Wimpy Bar adore them. Campbell's matiness was real. He was interested in people. He would sit in the canteen we all used, and talk to compositors, tape boys or the latest recruit to the staff. Nobody could be better suited to keep the loyalty of a temperamental team, and hold it together amid external attacks." (33) During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. He argued: "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism." (34) Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Francis Beckett pointed out: "Pollitt believed, as did many in the 1930s, that only the Soviet Union stood between the world and universal Fascist dictatorship. On balance, he reckoned Stalin was doing more good than harm; he liked and admired the Soviet leader; and persuaded himself that Stalin's crimes were largely mistakes made by subordinates. Seldom can a man have thrown away his personal integrity for such good motives." (35) However, according to his biographer, John Mahon, Pollitt found Khrushchev's speech upsetting: "Pollitt was far too human a person to regard the Stalin disclosures with personal detachment, they were as painful for him as far for thousands of other responsible Communists, and he was fully aware that they were giving rise to new and complex problems for the Party. Immediately following the Congress, he showed visible signs of physical exhaustion." On 25th April, 1956, he experienced a loss of ability to read following a haemorrhage behind the eyes. Unable to do his job properly he resigned as general secretary of the Communist Party. (36) James Friell (Gabriel), the political cartoonist on the Daily Worker, argued that the newspaper should play its part in condemning Stalinism. Gabriel drew a cartoon that showed two worried people reading the Khrushchev speech. Behind them loomed two symbolic figures labelled "humanity" and "justice". He added the caption: "Whatever road we take we must never leave them behind." As a fellow worker at the newspaper, Alison Macleod, pointed out in her book, The Death of Uncle Joe (1997): "This brought some furious letters from our readers. One of them called the cartoon the most disgusting example of the non-Marxist, anti-working class outbursts." However, Macleod went on to point out that a large number of party members shared Friell's sentiments. (37) Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. (38) Peter Fryer, the Daily Worker journalist in Budapest was highly critical of the actions of the Soviet Union, and was furious when he discovered his reports were censored. Fryer responded by having the material published in the New Statesman. As a result he was suspended from the party for "publishing in the capitalist press attacks on the Communist Party." Campbell now sent the loyal Sam Russell to report on the uprising. (39) Malcolm MacEwen, one of the journalists drafted a petition on the reporting of the uprising and persuaded nineteen out of the thirty-one staff of the newspaper to sign it. MacEwen made reference to Edith Bone, a journalist from the Daily Worker who had been in a Budapest prison since 1949. "The imprisonment of Edith Bone in solitary confinement without trial for seven years, without any public inquiry or protest from our Party even after the exposure of the Rajk trial had shown that such injustices were taking place, not only exposes the character of the regime but involves us in its crimes. It is now clear that what took place was a national uprising against an infamous police dictatorship." (40) John Ross Campbell turned on MacEwen. He later commented: "I don't think I've ever loved anybody more than I loved Johnnie Campbell". He was shocked when his best friend was suddenly transformed into his worst enemy, denouncing him so venomously that he knew what Laszlo Rajk and Rudolf Slánský must have felt. He felt he could not carrying on like this and he resigned from both the newspaper and the Communist Party. (41) Fryer told Campbell he must resign from the newspaper. Campbell pleaded with him to stay. He told Fryer that he had been in Moscow during the purges of the 1930s; he had known what was going on. But what could he do? How could he say anything in public, when the war was coming and the Soviet Union was going to be attacked. Alison Macleod, who watched this debate going on later commented: "This might have been some excuse for silence. However, Campbell was not silent in the 1930s. He wrote a book: Soviet Policy and its Critics, which was published by Gollancz in 1939. In this he defended every action of Stalin and argued the purge trials were genuine." (42) James Friell condemned Campbell for supporting the invasion. He told Campbell: "How could the Daily Worker keep talking about a counter-revolution when they have to call in Soviet troops? Can you defend the right of a government to exist with the help of Soviet troops? Gomulka said that a government which has lost the confidence of the people has no right to govern." When Campbell refused to publish a cartoon by Friell on the Hungarian Uprising he left the newspaper. "I couldn't conceive carrying on cartooning about the evils of capitalism and imperialism," he wrote, "and ignoring the acknowledged evils of Russian communism." (43) Campbell pleaded with the other journalists who were considering leaving the newspaper: "I am one of those who detest any possibility of a return to Stalinism. I have a very simple request to make to any comrades planning to leave the paper. Think it over for 24 hours! Do not do it in a way which will inflict the maximum injury on our paper... If a leading member of the staff leaves the paper at this moment it is not an ordinary act but a deadly blow." (44) Over 7,000 members of the Communist Party of Great Britain resigned over what happened in Hungary. One of them later recalled: "The crisis within the British Communist Party, which is now officially admitted to exist, is merely part of the crisis within the entire world Communist movement. The central issue is the elimination of what has come to be known as Stalinism. Stalin is dead, but the men he trained in methods of odious political immorality still control the destinies of States and Communist Parties. The Soviet aggression in Hungary marked the obstinate re-emergence of Stalinism in Soviet policy, and undid much of the good work towards easing international tension that had been done in the preceding three years. By supporting this aggression the leaders of the British Party proved themselves unrepentant Stalinists, hostile in the main to the process of democratisation in Eastern Europe. They must be fought as such." (45) Arnold Wesker had joined the Communist Party a few years earlier, had little difficulty resigning: "The Communist Parties of the world and especially of Britain suddenly found that Stalin and his policy which they once praised was now in disgrace; that the men they once criticised as reactionaries and traitors were not so; that the men whose deaths they once condoned were in fact innocent. There has been a fantastic spate of letters in the Daily Worker from Party members who are virtually in tears that they had ever been so lacking in courage.... It is as though they had all gone to a mass confessional and with terrible secrets in their heart now out in the open they feel new people." His mother, Leah Wesker, who had joined in the early days of the movement found the speech made by Nikita Khrushchev very distressing. "Leah, my mother... does not know what has happened, what to say or feel or think. She is at once defensive and doubtful. She does not know who is right. To her the people who once criticised the party and were called traitors are still traitors despite that the new attitude suggests this is not the case. And this is Leah. To her there was either black or white, communists or fascists. There were no shades... If she admits that the party has been wrong, that Stalin committed grave offences, then she must admit that she has been wrong. All the people she so mistrusted and hated she must now have second thoughts about, and this she cannot do - because having bound her politics so closely to her personality she must then confess a weakness in her personality. You can admit the error of an idea but not the conduct of a whole life." (46) In 1959 George Matthews became the new editor of the Daily Worker. According to Mike Power: "Matthews... became aware of a need to expand the paper's appeal beyond the largely male, industrial, working-class readership implied by its title, and, in April 1966, led its relaunch as the Morning Star. Increasing its interest for women, students and professional people - achieved by covering a wider range of topics and better use of pictures and cartoons - resulted in an immediate circulation increase to 100,000, though a substantial part of that figure represented subsidised sales to Soviet-bloc countries." (47) In January 1968 the Czechoslovak Party Central Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Antonin Novotny and he was replaced by Alexander Dubcek as party secretary. Soon afterwards Dubcek made a speech where he stated: "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness." During the next few weeks Dubcek announced a series of reforms. This included the abolition of censorship and the right of citizens to criticize the government. Dubcek described this as "socialism with a human face". (48) Newspapers began publishing revelations about corruption in high places. This included stories about Novotny and his son. On 22nd March 1968, Novotny resigned as president of Czechoslovakia. He was now replaced by a Dubcek supporter, Ludvik Svoboda. The following month the Communist Party Central Committee published a detailed attack on Novotny's government. This included its poor record concerning housing, living standards and transport. It also announced a complete change in the role of the party member. It criticized the traditional view of members being forced to provide unconditional obedience to party policy. Instead it declared that each member "has not only the right, but the duty to act according to his conscience." The new reform programme included the creation of works councils in industry, increased rights for trade unions to bargain on behalf of its members and the right of farmers to form independent co-operatives. (49) In July 1968 the Soviet leadership announced that it had evidence that the Federal Republic of Germany was planning an invasion of the Sudetenland and asked permission to send in the Red Army to protect Czechoslovakia. Alexander Dubcek, aware that the Soviet forces could be used to bring an end to Prague Spring, declined the offer. On 21st August, 1968, Czechoslovakia was invaded by members of the Warsaw Pact countries. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Czech government ordered its armed forces not to resist the invasion. Dubcek and Svoboda were taken to Moscow and soon afterwards they announced that after "free comradely discussion" that Czechoslovakia would be abandoning its reform programme. (50) John Ross Campbell, no longer reliant on the financial support of Moscow, condemned the invasion. So also did other leaders of the Communist Party of Great Britain including John Gollan, the general secretary. Gollan was on holiday at the time and it was left to his deputy, Reuben Falber, to issue a statement calling for the troops to be withdrawn. Falber later argued: "We had no doubt what we should do. It was our responsibility to declare publicly our total opposition to the Soviet-led intervention." Chris Myant, who claims that Falber was the man responsible for collecting funds from the Soviet Union, pointed out: "So the official who collected the Soviet money found himself on the steps of the party offices personally handing out the statement to the waiting reporters condemning the actions of his paymasters." (51) Monty Johnstone, who had been "shut out of top-level Communist Party affairs for almost a decade for asking awkward questions" published a pamphlet under the title Czechoslovakia's Struggle for Socialist Democracy. The previously loyal Sam Russell was sent to Czechoslovakia, by George Matthews, the editor of The Morning Star, to produce some pro-Soviet articles. These articles did not placate Moscow and decided to cut back on the funding of the CPGB. (52)The Daily Worker

Soviet Show Trials

The Second World War

Walter Holmes, William Rust, John Ross Campbell and Douglas Hyde (1939)The Cold War

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation Policy

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Beckett, The Enemy Within (1995)

He (William Rust) was a fine editor: a cynical boss who thumped the table in his furious rages, he nonetheless inspired journalists' best work. A tall and by now heavily built man, Rust was one of the Party's most able people, and one of the least likeable.

(2) Rajani Palme Dutt, The Daily Worker (25th January, 1930)

Capitalist sport is subordinate to bourgeois politics, run under bourgeois patronage and breathing the spirit of patriotism and class unity; and often of militarism, fascism and strike breaking. Sport is a hotbed of propaganda and recruiting for the enemy. Spectator sports [horse racing and football] are profit run professional spectacles thick with corruption. They are dope; to distract the workers from the bad conditions of their lives, to stop thinking, to make passive wage slaves. You cannot reconcile revolutionary politics with capitalist sport!

(3) Claud Cockburn, The Daily Worker (21st November, 1936)

From the main streets you could already hear quite clearly the machine-gun and rifle fire at the front.

Already shells began to drop within the city itself. Already you could see that Madrid was after all going to be the first of the dozen or so big European capitals to learn that "the menace of Fascism and war" is not a phrase or a far-off threat, but a peril so near that you turn the corner of your own street and see the gaping bodies of a dozen innocent women lying among scattered milk cans and bits of Fascist bombs, turning the familiar pavement red with their gushing blood.

There were others besides the defenders of Madrid who realised that, too.

Men in Warsaw, in London, in Brussels, Belgrade, Berne, Paris, Lyons, Budapest, Bucharest, Amsterdam, Copenhagen. All over Europe men who understood that "the house next door is already on fire" were already on the way to put their experience of war, their enthusiasm and their understandings at the disposal of the Spanish people who themselves in the months and years before the Fascist attack had so often thrown all their energies into the cause of international solidarity on behalf of the oppressed and the prisoners of the Fascist dictatorships in Germany, Hungary and Yugoslavia.

It was no mere "gesture of solidarity" that these men - the future members of the International Brigade - were being called upon to carry out.

The position of the armies on the Madrid fronts was such that it was obvious that the hopes of victory must to a large extent depend first on the amount of material that could be got to the front before the German and Italian war machines smashed their way through, and secondly, on the speed with which the defending force of the People's Army could be raised to the level of a modern infantry force, capable of fighting in the modern manner.

(4) Claud Cockburn, The Daily Worker (8th February, 1937)

When the church bells ring in Malaga that means the Italian and German aeroplanes are coming over. While I was there they came twice and three times a day. The horror of the civilian bombing is even worse in Malaga than in Madrid. The place is so small and so terribly exposed.

When the bells begin ringing and you see people who have been working in the harbour or in the market place, or elsewhere in the open, run in crowds, you know that they are literally running a race against death.

But the houses in Malaga are mostly low and rather flimsy, and without cellars. Where the cliffs come down to the edge of the town, the people make for the rocks and caves in which those who can reach them take refuge. Others rush bounding up the hillside above the town.

Those in the town, with an air of infinite weariness, wait behind the piles of sandbags which have been set up in front of the doorways of the apartment blocks. Though they are not safe from bombs falling on the houses, they are relatively protected from an explosion in the street and from the bullets of the machine-guns.

Sometimes you can see the aeroplane machine-gunner working the gun as the plane swoops along above the street.

If you were to imagine, however, that this terribly hammered town is in a state of panic you would be wrong. Nothing I have seen in this war has impressed me more than the power of the Spanish people's resistance to attack than the attitude of the people as seen in Malaga.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject