Nancy Carole Tyler

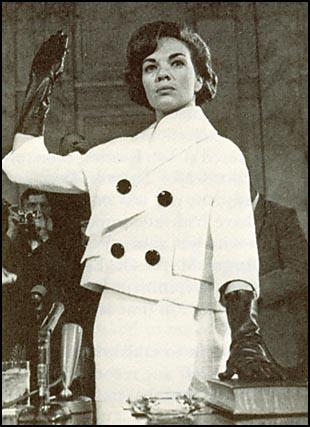

Nancy Carole Tyler was born in Lenoir City, Loudon County, Tennessee on 9th April, 1939. According to G. R. Schreiber: "She (Tyler) had big bright eyes, a good figure, a determined chin, and a certificate to prove she had been named Miss Loudon County of 1957." (1)

Tyler moved to Washington D.C. and her first job was on the secretarial staff of a congressman from Delaware. She lived with Mary Jo Kopechne, who worked for George Smathers. (2)

It was not long before Tyler began a relationship with Bobby Baker, a close associate of Lyndon B. Johnson. "What started as a harmless affair eventually evolved into a romance, and I grew to love Carole Tyler. Young and beautiful and vivacious, at once a former beauty queen and a quick mind with a flair for politics, she was not difficult to love. Though I knew the guilt of a longtime family man with a loyal wife and five children, I did nothing to discourage our romance once it began." (3)

The author of The Bobby Baker Affair (1964) pointed out: "Nancy Carole joined Bobby's staff with the title of telephone page for the majority, a job which paid her $5,687.56 to start. Her work was more than satisfactory and she was rewarded with a fast series of pay raises. Almost two months to the day after she joined Bobby's staff she got her first increase to $6,052.11. Four months later, in August, 1961, her salary was boosted to $6,538.19 and that October - eight months after she joined his staff Bobby promoted Nancy Carole to clerk for the secretary to the majority, a kind of administrative assistant, and raised her pay to $7,753.34. October 16, 1962... Nancy Carole's salary was boosted again, this time to $8,296.07." (4) In November, 1962, Tyler moved into the townhouse Baker purchased. After an initial down payment of $28,800 he paid the $238 monthly payments. "Carole's place in Southwest Washington, an upper-middle-class redevelopment area of closely packed high-rises and town houses, became the center where Bobby's friends, male and female, often met. How Bobby spent his off-duty hours was more or less common knowledge on the Hill, but those were the days when Bobby was on top, when there seemed nothing unusual about his diversions and when no one thought that, as Senate practices go, there was anything there to get excited about." (5) Time Magazine became aware of the relationship: "One subject of considerable curiosity was Carole Tyler, 24, a shapely (5 ft. 6 in., 35-26-35) Tennessee girl who won the title of 'Miss Loudon County' before she turned up in Washington in 1959. Three years later she was Baker's private secretary at $8,000 a year. Chain-smoking, martini-drinking, party-loving Carole also became a favorite in Baker's high-flying circle of acquaintances." (6) In 1961 Baker, with the help of Tyler, established the Quorum Club. This was a private club in the Carroll Arms Hotel on Capitol Hill. "Its membership was comprised of senators, congressmen, lobbyists, Capitol Hill staffers, and other well-connecteds who wanted to enjoy their drinks, meals, poker games, and shared secrets in private accommodations". (7) Time Magazine reported: "Among the 197 members are many lobbyists and several governmental figures, including Democratic Senators Frank Church of Idaho, Daniel Brewster of Maryland, J. Howard Edmondson of Oklahoma and Harrison Williams of New Jersey. Among Republican members are two Congressmen, Montana's James Battin and Ohio's William Ayres." (8) Rumours began circulating that Baker was involved in corrupt activities. Although officially his only income was that of Secretary to the Majority in the Senate, he was clearly a very rich man. One journalist pointed out: "How do you build a two million dollar fortune in eight years on a salary of less than $20,000? The answer is that Bobby found it easy because so many people were ready to help him." (9) Baker was investigated by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. He later recalled: The newspapers had a number of articles, The Washington Post particularly. I had always heard stories about Bobby Baker, about all his money and free use of money.... Our first involvement in it came, I suppose, in a conversation I had with Ben Bradlee... who had some information. I can't remember exactly what it was, but they printed it in Newsweek. He asked me if we would look into it, and I said we would look into it." (10) Robert Kennedy discovered Baker had links to Clint Murchison and several Mafia bosses. Evidence also emerged that Lyndon B. Johnson was also involved in political corruption. This included the award of a $7 billion contract for a fighter plane, the F-111, to General Dynamics, a company based in Texas. On 7th October, 1963, Bobby Baker was forced to resign his post. Soon afterwards, Fred Korth, the Navy Secretary, was also forced to resign because of the F-111 contract. (11) Reports circulated in Washington that the White House was pushing the Baker investigation to embarrass Lyndon B. Johnson. The journalist, W. Penn Jones claimed that it was Nancy Carole Tyler who leaked the story that John F. Kennedy wanted George Smathers to replace Johnson as his vice president in 1964. "Bobby Baker was about the first person in Washington to know that Lyndon Johnson was to be dumped as the Vice-Presidential candidate in 1964. Baker knew that President Kennedy had offered the spot on the ticket to Senator George Smathers of Florida... Baker knew because his secretary. Miss Nancy Carole Tyler, roomed with one of George Smathers' secretaries." (12) Robert Kennedy later denied this: There were a lot of stories that my brother and I were interested in dumping Lyndon Johnson and that I'd started the Bobby Baker case in order to give us a handle to dump Lyndon Johnson. Well, number one, there was no plan to dump Lyndon Johnson. That didn't make any sense. Number two, I hadn't gotten really involved in the Bobby Baker case until after a good number of newspaper stories had appeared about it.... There were a lot of stories then, after November 22, that the Bobby Baker case was really stimulated by me and that this was part of my plan to get something on Johnson. That wasn't correct." (13) On 22nd November, 1963, a friend of Baker's, Don B. Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his Senate Rules Committee that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for this business. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds also had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". (14) Reynolds' testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. "Reynolds was stunned. If President Kennedy was dead, then Lyndon Johnson, the man about whom he had been talking, was President of the United States." Reynolds told his lawyer: "Giving testimony involving the Vice President is one thing, but when it involves the President himself, that is something else. You can just forget that I ever said if you want to." (15) In November, 1963, Nancy Carole Tyler was called before the Senate Rules Committee, who were investigating the activities of Bobby Baker. She took the fifth amendment and refused to provide any information that would implicate Bobby Baker in any corrupt activities. One magazine reported: "Chain-smoking, martini-drinking, party-loving Carole also became a favorite in Baker's high-flying circle of acquaintances". In December, 1962 "Carole took up housekeeping in a cooperative townhouse at 308 N Street S.W., just a short ride from the Capitol. It was a well-furnished apartment, with prints on the walls, silk draperies in the bedrooms, lavender carpeting in the bathrooms. The parties there were lively. The twist was danced both inside the house and on the patio outside; the convivial drinking and animated chatter lasted long into the night. Some nearby residents noted that visitors appeared in the daytime as well as the evening." (16) Time Magazine reported that Bobby Baker was back before the Senate Rules Committee and the chairman was very interested in his relationship with Tyler. It was pointed out that he had identified her as a "cousin" for purposes of buying a Washington townhouse. To get around a stipulation that houses in the development be occupied by the owner or his family, Baker said his "cousin, N. C. Tyler," would live there. "N. C. Tyler was Nancy Carole Tyler, 24, a sultry, shapely brunette who, whatever her relationship to Baker may be, is certainly no kin." (17) Nancy Carole Tyler moved back to Tennessee "but after the headlines cooled off she returned to Washington to work" for Baker as his bookkeeper at the Carousel Hotel, near Ocean City, Maryland. Baker resumed his romance with Tyler: "I loved Carole, but I refused to leave my family for her. This led to stormy scenes in which she sometimes cried or threatened to commit suicide. Despite such scenes there were moments of fun and sharing." (18) On 9th May, 1965, Nancy Carole Tyler met Robert H. Davis, and agreed to go on a sightseeing tour over the eleven-mile-long island on which the hotel had been built in his Waco biplane. (19) Baker later recalled: "Witnesses later said that the single-engine aircraft approached the Carousel, buzzed it a few times at low altitudes, and then began to pull up sharply as it banked into a turn taking it out over the Atlantic. The aircraft failed to come out of the turn. It hit the water nose-first at high speed and sank like a stone, only a couple of hundred yards from the Carousel.... When I saw Carole's body dressed in a green pants suit I had bought her, I broke down and cried like a baby." (20)Nancy Carole Tyler and Bobby Baker

Quorum Club

Senate Rules Committee

Death of Nancy Carole Tyler

Primary Sources

(1) W. Penn Jones Jr, Texas Midlothian Mirror (31st July, 1969)

Bobby Baker was about the first person in Washington to know that Lyndon Johnson was to be dumped as the Vice-Presidential candidate in 1964. Baker knew that President Kennedy had offered the spot on the ticket to Senator George Smathers of Florida... Baker knew because his secretary. Miss Nancy Carole Tyler, roomed with one of George Smathers' secretaries. Miss Mary Jo Kopechne had been another of Smathers' secretaries. Now both Miss Tyler and Miss Kopechne have died strangely.

(2) Time Magazine (6th November, 1963)

Out of the hearing room and into the arms of waiting newsmen stepped Arizona's Democratic Senator Carl Hayden, a member of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. "No comment," grumbled Hayden. Next out was Nebraska's Republican Senator Carl Curtis. "I can't tell you a thing," said he.

The remaining members of the nine-man committee were equally uncommunicative about what they had found out so far in their investigation of Bobby Gene Baker, 35, who last month precipitously resigned from his $19,600-a-year position as Secretary for the Senate Majority. Indeed, not even Delaware's Republican Senator John Williams, who appeared before the committee as a witness against Baker, would say what was going on.

Why this sudden affliction of senatorial lockjaw? The answer seemed obvious: Baker is involved in a scandal of major proportions, and the Senate plainly feared that some of its own members are in it with him. Yet the Senate's self-protective silence had an unintended effect, creating a climate in which talk and speculation flourished with tales of illicit sex, influence peddling and fast-buck financial deals.

One subject of considerable curiosity was Carole Tyler, 24, a shapely (5 ft. 6 in., 35-26-35) Tennessee girl who won the title of "Miss Loudon County" before she turned up in Washington in 1959. Three years later she was Baker's private secretary at $8,000 a year. Chain-smoking, martini-drinking, party-loving Carole also became a favorite in Baker's high-flying circle of acquaintances.

Last December Carole took up housekeeping in a cooperative townhouse at 308 N Street S.W., just a short ride from the Capitol. It was a well-furnished apartment, with prints on the walls, silk draperies in the bedrooms, lavender carpeting in the bathrooms. The parties there were lively. The twist was danced both inside the house and on the patio outside; the convivial drinking and animated chatter lasted long into the night. Some nearby residents noted that visitors appeared in the daytime as well as the evening. "A lot of people used to come through the back gate," recalls one neighbor. "That struck us as strange. Most of our guests come through the front door."

Carole shared the house for a time with another girl, Mary Alice Martin, a secretary in the office of Florida's Democratic Senator George Smathers. But neither girl owned the heavily trafficked house they lived in. The owner was Bobby Baker, who bought it for $28,000 on a down payment of $1,600. On the FHA forms that he signed, Baker listed both girls as the tenants of the house, said that Carole was his "cousin." She resigned from her job as a Senate employee at the same time Baker did, and has not since been available to inquiring newsmen.

Investigators were also sifting through stories that concerned several call girls who operated in this rarefied atmosphere. Among these was a young German woman who was asked to leave the U.S. after FBI agents showed her dossier to other interested authorities. She was Ellen Rometsch, 27, a sometime fashion model and wife of a West German army sergeant who was assigned to his country's military mission in Washington. An ambitious, name-dropping, heavily made-up mother of a five-year-old boy, Elly was a fixture at Washington parties. In September, five weeks after the Rometsches were shipped back to West Germany, her husband Rolf, 25, divorced her on the ground of "conduct contrary to matrimonial rules." Last week, while Elly hid out on her parents' farm near Wuppertal, Rolf spoke ruefully of his Washington experience, said that he "had no idea what was going on behind my back. It's a case of a woman who falls for the temptation of a sweet life her husband can't afford."

One repository of the sweet life was the Quorum Club, located in a three-room suite at the Carroll Arms Hotel, just across the street from the new Senate Office Building. Elly is remembered as a hostess there.

Bobby Baker was a leading light of the "Q Club." He helped organize it, was a charter member and served on the board of governors. The club, so its charter says, is a place for the pursuit of "literary purposes and promotion of social intercourse." Actually it was open to anyone with a literate bankroll: initiation fee, $100; yearly dues, $50. Among the 197 members are many lobbyists and several governmental figures, including Democratic Senators Frank Church of Idaho, Daniel Brewster of Maryland, J. Howard Edmondson of Oklahoma and Harrison Williams of New Jersey. Among Republican members are two Congressmen, Montana's James Battin and Ohio's William Ayres.

Many members were quick to point out that the club is a handy place to dine ("My wife is fond of the steak and sandwiches," said Bill Ayres) as well as a convenient spot for cocktails. Decorated to the male taste, the club's dimly lit interior sports prints and paintings of women with imposing façades, leather-topped card tables, a well-stocked bar, a piano and, most convenient of all, a buzzer that is wired to the Capitol so that any Senator present can be easily summoned to cast his vote on an impending issue.

The Q Club was a useful spot for meeting influential people in business and politics. Such people, in turn, were useful to Bobby Baker in his breathless pursuit of a buck. It was, by any standard, a successful pursuit, for Baker's net worth rose to something around $2,000,000. That income, presumably, enabled Baker and his wife Dorothy, who has an $11,000-a-year job with a Senate committee, to move recently into a $125,000 house near the home of Bobby's friend and longtime Senate sponsor, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, in Washington's Spring Valley section.

Though he was well liked by many people, Bobby unquestionably left behind him a roiling trough of bitter enemies. One man who thinks that Bobby did him dirt is an old friend named Ralph Hill, president of Capitol Vending Co. Hill is suing Baker for $300,000. He claims that through Bobby he got a contract for the vending-machine concession at Melpar Inc., a Virginia electronics firm. Hill charges that Baker thereafter demanded a monthly cut from Hill in return for his good will.

Hill claims that for 16 months he appeared regularly at Baker's Capitol office with envelopes containing cash - $5,600 all told. Last March the Serv-U Corp. - a competing vending-machine firm, of which Baker's law partner Ernest Tucker is board chairman - moved to buy Capitol Vending's outstanding stock. Hill resisted, and Baker warned him that he would see to it that Melpar canceled Capitol Vending's contract. Sure enough, in August 1963, Melpar said it would.

Baker's dealings with the Novak family of Washington started out pretty well. Builder Alfred Novak and his wife were friendly with the Bakers. Early in 1960, Novak agreed to lay out $12,000 so that Baker could cash in on a good stock tip. They agreed to share fifty-fifty in the profits. And they did just that. The investment brought in $75,321, and Baker got his 50% - $37,660 - without having invested a cent of his own money.

It was with the Novak family that Baker launched a $1,200,000 motel, the Carousel, in Ocean City, Md. For the Novaks the experience was a painful one. Baker, who initially invested $290,000, borrowed on promissory notes from the Serv-U Corp., began campaigning for more money from the Novaks; he wanted to build a restaurant addition to the motel, then a nightclub. The Novaks could not afford the extra investment, sold some of their shares to Baker. The Novaks were disillusioned in their partner, and Novak became deeply depressed. Five months before the Carousel opened for business, he died at 44 of a heart attack. Says Gertrude Novak of Baker's handling of financial matters: "We felt we were being pushed up against the wall."

In any event, the Carousel, billed as a "high-style hideaway for the advise and consent set," opened with a merry party. Two hundred Washington big shots traveled to the event in chartered buses. Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson were there, and Entrepreneur Baker was all over the place.

Baker also had a variety of other financial interests. Apart from his law firm, he was an agent for the Go Travel agency of Washington and invested in a Howard Johnson's motel in North Carolina. But he did not restrict himself solely to million-dollar enterprises. On at least one occasion, he showed an interest in the money problems of his Senate page boys. Young Boyd Richie was a $403-a-month telephone page in Baker's office. Richie, a 17-year-old Texan, roomed with another page, Walter J. Stewart, and paid Stewart $50 a month rent. Stewart, it seems, was on temporary military duty and so was not on the Senate payroll. One day he told Richie to give him an additional $50 a month - on orders of Bobby Baker.

For three months, Richie dutifully forked over the extra money, but the more he thought about it the angrier he became. It happened that Richie was dating Lucy Baines Johnson, L.B.J.'s 15-year-old daughter. So one evening when he came to call for Lucy, Richie confronted the Vice President in his den and told him what was going on. Next day Lyndon informed the boy that he need not continue the payoff and would be permitted to live rent-free for three months at Stewart's place to make up for his losses. Baker himself admitted that "some of Boyd Richie's money had been deferred. After all, he was just a teenager and making a good salary."

Another good Senate friend of Baker's was Oklahoma's millionaire Democrat Robert S. Kerr (Kerr-McGee Oil Industries Inc.). Before he died last January, Kerr was one of the Senate's most powerful members. At one point, Baker got a $275,000 mortgage on Serv-U Corp. from Oklahoma City's Fidelity National Bank, of which the Kerr family owns 12%.

A couple of weeks ago, Baker journeyed to Oklahoma City to see Kerr-McGee's President Dean A. McGee and the late Senator's son, Robert Jr. He said he wanted to find proof of the fact that Senator Kerr had once handed him $40,000 as a gift, told McGee that the Senator had said, "I want you to have the money. Be sure and report it on your income tax." But both McGee and young Kerr denied that the Senator had given Baker any money, insisted that there were no records of any gift. "I think I would know it if Dad had given him $40,000," says Kerr. Adds McGee: "There's only one person who really knows, and that's the Senator, and he's dead. Baker seemed to be concerned about it. He gave me the impression it was a problem."

Obviously, a lot of deep-digging investigating remained to be done before the scandalous skeins of Bobby Baker's high life could be untangled and strung back together in a definitive way. But it was just as certain that the U.S. Senate was doing itself no service by its closed-door, clam-mouthed handling of the case. For the way things were going, instead of only a handful of members suffering embarrassment or worse, the Senate and almost all its members were being subjected to suspicion.

(3) Time Magazine (6th March, 1964)

With the exaggerated gestures of a man who feels the eyes of scrutiny, the short, fox-faced witness removed his serious blue fedora, took off the velvet-collared overcoat with the lavender silk lining, and with well-manicured hands smoothed back a wisp of brown hair. His bright eyes stole briefly across the gathered crowd and looked away again. Then, clutching a black attaché case imprinted with his silver initials, Robert Gene Baker, 36, the whizbang from Pickens, S.C., hurried into a hearing room in the old Senate Office Building.

Hot-eyed TV lights glared down at the overflow of spectators lining the marble walls. Photographers jostled and cursed as they tried to get close to Baker, who himself had some difficulty squeezing through to the witness table. Bobby Baker grinned, waved to familiar faces, and, for the moment at least, appeared to be enjoying himself hugely. Finally seated, he extracted a pack of Salems from his coat pocket, laid it carefully alongside the Bible upon which he would soon be sworn in. Next he produced a typewritten sheet of paper and positioned it on the table just so.

Call It Off? His props in place, Baker nodded to some of his old employers—members of the Senate Rules Committee—who sat facing him. He also had a little joke with reporters, whom he had been assiduously avoiding. "Why don't you fellows call this whole thing off," he stage-whispered to the nearby press table, "so we can all get a rest?"

Bobby Baker was not the only one who would have liked to see the whole thing called off. His presence was a source of intense embarrassment to Democratic Senators. Up to five months ago, when he became the central figure in the gamiest Washington scandal in years, Baker was secretary to the Senate's Democratic majority.

As such, he was beyond question the U.S. Senate's most influential employee. He had been a particular protégé of the Senate's two most powerful Democrats —Oklahoma's late Senator Robert Kerr and longtime Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson. Baker made it his unending business to know things—and what he didn't know about the Senate and its members probably was not worth the trouble. He knew who was against what bill and why. He knew who was drunk. He knew who was out of town. He knew who was sleeping with whom. He influenced committee assignments. He influenced legislation. He came to be known as "the 101st Senator." And he indulged in some vast moonlighting schemes that helped him parlay his $19,612-a-year Government salary into a fortune of up to $2,000,000.

It was the public disclosure of one of those schemes that led last October to Baker's forced resignation as Senate majority secretary. Ever since, the Rules Committee, chaired by North Carolina's colorless, cautious Senator B. Everett Jordan, has been investigating the Baker case.

Finally, last week, came Bobby Baker's time to testify. It was plain that he did not intend to be helpful. Now smirking, now looking serious, he sat silently as his attorney, famed Trial Lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, argued successfully to have television cameras removed from the room. A fascinated TV audience watched as the cameras withdrew and then focused on the closed door. When questions started coming his way, Bobby steadfastly refused to answer them, invoking not only the familiar Fifth Amendment, but the First, Fourth and Sixth as well. Reading from the typewritten statement that he had placed in front of him, he insisted that the hearing had no "true legislative purpose," and was "an unconstitutional invasion by the legislative branch into the proper function of the judiciary."

Seldom did Baker deviate from his prepared statement. One time was when Committee Counsel Lennox Polk McLendon, 74, a self-described "country lawyer" from North Carolina, noted that Baker had previously refused to turn his records over to the committee, hopefully suggested that by now Baker might have changed his mind. "You don't know me," snapped Baker. "Whatever reputation I made in the Senate, my word was my bond. When I told you I was not going to testify, that ended it." Again, Rhode Island's Democratic Senator Claiborne Pell asked if Baker, who had begun his career as a Senate pageboy, had any ideas about improving pageboy hiring practices. To a fatuous question, came a gratuitous answer. Advised Bobby: "There are many fine orphan boys in the District.

It would be fine if you tried to utilize these young men."

Aside from those occasions, Baker remained obdurate during 2½ hours and 125 questions. Still, the questions themselves gave some indication of the extent of Baker's wheeling-dealing activities. And in many instances those questions had already been answered or partly answered by previous committee witnesses or by other evidence uncovered during the Baker investigation.

Had he used his Capitol office to transact private business, such as dispensing large amounts of cash?

Gertrude Novak, a Senate clerk who, with her late husband, was a partner in Baker-inspired motel and stock ventures, testified that she frequently went to Baker's office to pick up sums ranging from $1,000 to $13,300, always in cash. She said that the money was for operating expenses at the Carousel Motel in Ocean City, Md. Baker and the Novak family built the $1,200,000 motel in 1962, later sold it to Serv-U Corp., a vending-machine firm in which Baker is a major stockholder.

Had he identified his secretary, Carole Tyler, as a "cousin" for purposes of buying a Washington townhouse?

To get around a stipulation that houses in the development be occupied by the owner or his family, Baker said his "cousin, N. C. Tyler," would live there. "N. C. Tyler" was Nancy Carole Tyler, 24, a sultry, shapely brunette who, whatever her relationship to Baker may be, is certainly no kin.

(4) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

Carole Tyler had resigned from her job in the Senate shortly after I had quit mine; as I did, she took the fifth amendment before the Senate Rules Committee. For a while she returned to her home in Tennessee, but after the headlines cooled off she returned to Washington to work for me-which, of course, made new headlines. We had continued our romance. I loved Carole, but I refused to leave my family for her. This led to stormy scenes in which she sometimes cried or threatened to commit suicide. Despite such scenes there were moments of fun and sharing. Certainly I was not prepared for what happened to her on a Sunday in early May of 1965.

Carole was at the Carousel, where she was working as my bookkeeper. On Sunday morning she and her roommate, a young woman named Dee McCartney, began having drinks with a West Virginia man, Robert O. Davis, who had been vacationing at the Carousel for about a week. She originally had intended to take a sightseeing tour over the eleven-mile-long island on which the Carousel was built, in Davis's private plane, but the morning weather was judged too soupy for flying. They continued to drink; observers later told me the pilot appeared to be pretty tipsy. About 2 p.m., Robert Davis and Carole Tyler drove to the Ocean City airport, the weather having turned bright and sunny, and went up in his airplane. Witnesses later said that the single-engine aircraft approached the Carousel, buzzed it a few times at low altitudes, and then began to pull up sharply as it banked into a turn taking it out over the Atlantic. The aircraft failed to come out of the turn. It hit the water nose-first at high speed and sank like a stone, only a couple of hundred yards from the Carousel.

I was in Washington when someone called to tell me the bad news. My wife and I, and my physician, Dr. Joseph Bailey, chartered a small airplane and flew to Ocean City as quickly as we could. It was nearing nightfall by the time we arrived. I boarded one of the Coast Guard boats searching for the wreckage, and I was on hand when the plane was pulled from the deep shortly after 1 p.m. When I saw Carole's body, dressed in a green pants suit I had bought her, I broke down and cried like a baby. Dr. Bailey told me that she and the pilot had died instantly of massive head injuries. The hardest thing I ever had to do was call Carole's mother and tell her that her daughter was dead.

Dorothy and I were among twenty-odd of Carole's Washington friends who accompanied her body on the train to Lenoir City, Tennessee, for burial. Through those long, dismal rites I felt that I had bottomed out for sure, that life never would be good again, and I knew that not for a long time-if ever-would I care for anyone as deeply as I had cared for Carole. She had stood by me with unswerving loyalty and affection when others had cut and run. She was only twenty-six, I thought. She had only started to live. God, what a waste of beauty and goodness.

(5) Milton Viorst, Hustlers and Heroes (1971)

After a hard day at the Senate, when anyone else would be glad to get home to bed, Bobby Baker would be starting the evening's fun with the Mexican hat dance. The frolic might go on till dawn. Bobby's secretary was Carole Tyler, a Tennessee beauty with whom he was often seen in public. Carole's place in Southwest Washington, an upper-middle-class redevelopment area of closely packed high-rises and town houses, became the center where Bobby's friends, male and female, often met. How Bobby spent his off-duty hours was more or less common knowledge on the Hill, but those were the days when Bobby was on top, when there seemed nothing unusual about his diversions and when no one thought that, as Senate practices go, there was anything there to get excited about...

The... sex's arrow struck again, when a neighbor of Carole Tyler's, a newspaper reporter, discovered, in scanning the list of eligible voters in the residential co-op, that Bobby Baker was actually the owner of Carole's house, now widely known for its lavender carpet (the same, by the way, with which the Baker bedroom in Spring Valley and the lobby of the Carousel are decorated). In explanation, Bobby has since declared: "She and her roommate were paying $250 a month for an apartment. I fussed at her. I said you're getting up old enough where you ought to be building up a little equity in a place. So they went and they found a place that they wanted. And because they didn't have the net worth to get it, I agreed to put a financial statement in whereby they could get it and build up some equity. Is that criminal or illegal or un-American to try to help two young ladies build up equity?" But the public was scarcely interested in looking at Carole's house as a token of philanthropy. It became a tourist attraction and dozens of gawkers passed it in their cars. But Bobby was undeterred. He continued to give parties there regularly. If he encountered an old Senate acquaintance, many of whom lived in the neighborhood, he didn't turn up his coat collar but, on the contrary, said in his usual friendly way, "Hello, how are you? Nice to see you again." On weekends he even washed Carole's car in the parking lot. If Bobby was, in reality, embarrassed by his publicity, he managed to conceal it very well...

Carole Tyler used to be a normal visitor to the Carousel. Her figure was familiar on the beach and in the bar. Then, in May, 1965, she was killed. Carole was joyriding in a Waco biplane, when the pilot made a flip, failed to pull out in time and plunged into the Atlantic directly in front of the motel. Bobby was there when they brought her body ashore. He knew that the assembled crowd, mostly townspeople in threadbare clothes, expected him to say something appropriate. But there wasn't much you could say about Carole, beyond noting that she was a very pretty girl from a small town in Tennessee who found zest in Washington and lived her life with more gusto than it required. Her friends agreed later that she had chosen a kicky way to go. "All I can say," Baker uttered finally to the bystanders, "is that she was a very great lady." Baker was more accurate than that in taking head counts in the Senate. Whatever Carole was, that wasn't it. But Bobby had style and he wasn't going to let Carole, who was dear to him, leave the world without some of it as adornment.

(6) G. R. Schreiber, The Bobby Baker Affair (1964)

Once the cat was out of the bag that Bobby Baker, a married man, had bought a townhouse for his beautiful young secretary, it was inevitable that girls would begin to figure in the Senate's much heralded investigation of Bobby's outside activities. As it happens, girls figure in much that goes on in Washington, both because there are so many of them in the myriad government offices and because Washington is a city on a perpetual party. And what are parties - cocktail or otherwise - without pretty girls?

Single girls outnumber other people by a wide margin in Washington. A passably attractive girl in a government office can go off to a party seven nights out of seven if she is so inclined. She can go with a male fellow worker who prefers not to take his wife. Or she can be window dressing (more if she prefers) at the parties given by the free spending lobbyists. There are always business executives from out of town who hate to eat alone.

A girl in Washington, like most girls anywhere, can go out as often and as far as her schedule and her scruples allow. The difference between Washington and other cities is that there are so many more opportunities.

Nancy Carole Tyler had come up to Washington from Lenoir City, Tennessee, a town of five thousand citizens some twenty miles from Knoxville. She had big bright eyes, a good figure, a determined chin, and a certificate to prove she had been named Miss Loudon County of 1957. Her first job was on the secretarial staff of a congressman from Delaware. Miss Loudon County got her picture in the Washington newspapers for the first time when she was photographed in 1960 at a statue raising ceremony at the Capitol. The newspapers reported that Miss Tyler had posed for the arms of the statue "Peace." It may have been that Bobby saw the photograph of Miss Loudon County, her long brown hair tumbling to her shoulders, a wide smile crinkling her eyes and showing her beautifully even teeth. Whether Bobby saw the picture or not, Nancy Carole moved over from the House of Representatives to the office of the secretary to the senate majority in February, 1961, and ever after where Bobby was, there was Nancy.

Nancy Carole joined Bobby's staff with the title of telephone page for the majority, a job which paid her $:i,687.56 to start. Her work was more than satisfactory and she was rewarded with a fast series of pay raises. Almost two months to the day after she joined Bobby's staff she got her first increase to $6,052.11. Four months later, in August, 1961, her salary was boosted to $6,538.19 and that October - eight months after she joined his staff Bobby promoted Nancy Carole to clerk for the secretary to the majority, a kind of administrative assistant, and raised her pay to $7,753.34.

October 16, 1962, one month before she moved into the townhouse Bobby purchased, Nancy Carole's salary was boosted again, this time to $8,296.07. All in all it was a history of consistently good merit increases and the take home pay was not at all bad for the twenty-three-year-old Miss Loudon County. Bobby wrote out a check to cover the down payment on the $28,800 townhouse and wrote checks for the $238 monthly payments, so Nancy Carole had enough left over from her salary to give lots of parties on her own in her attractive patio.