Robert Lamphere

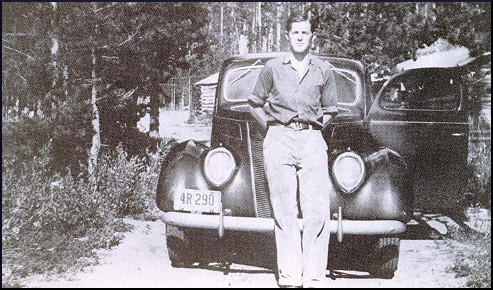

Robert Joseph Lamphere was born in Wardner, Idaho, on 14th Febuary, 1918. Lamphere's father leased a small mine near Mullan. "My father had become a Teaser. This was a man who leased the rights to mine someone else's underground ore deposits - silver, lead and zinc in this area - and who hired hands to do the actual work... Mullan was a tough little town... A little professional boxing instruction helped me in those tiffs. My father and mother expected all three of us to do well in school, and we did. " (1)

Lamphere attended the University of Idaho. "To help defray the expenses, during the summer I worked in the mines. The first time, my father made sure I got every dirty job available so he wouldn't appear to be playing favorites; succeeding summers, I worked deeper in the mines, and for the larger company that owned them. I preferred working down in the hole because I was treated more as an equal. The air was stale, hot and humid, and we twisted the sweat out of our socks when we got home at night. In the depths there were more fights. Twice I had to face down other men; I didn't like that, but my father heard of one of the incidents and it seemed to impress him. The other miners started to cajole me into joining the union until they realized they didn't want a boss's son at their meetings." (2) Robert Lamphere left the University of Idaho before completing his degree. In 1940 he moved to Washington where he found work as a clerical auditor in the procurement division of the Treasury Department. In the evenings he completed his law degree at George Washington University. Lamphere then joined the FBI: "The FBI was known as an elite outfit. At a time when most adults had never gone to college, FBI men had graduate degrees; they were taller than the norm (over five foot seven); and they were exemplars of good upbringing and high moral standards. If I was somewhat attracted to the FBI's 'crime-busting' image, I was more attuned to the idea of being among the very best, and wanted to measure up to the high requirements for membership in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. My parents were dead, my hometown was left behind, and for me, the past was rapidly receding. Maybe I needed the structure the Bureau would provide, and perhaps I just sought a way to test myself. Either way, the FBI was a good choice." (3) Lamphere recalls that the young recruits developed a fear of J. Edgar Hoover: "Two ideas were continually drummed into us: pride at membership in an elite organization, and fear of failure. Eventually these two became completely intertwined and inseparable feelings. Inculcation of fear began on our first day, and dread of our superiors' wrath never let up during my whole career in the FBI. We were constantly afraid of earning the displeasure of Hoover - who, we learned, could fire any of us at any time for any infraction of the multitudinous rules that governed the conduct of an FBI man, on or off the job. Unlike other government employees, we in the FBI were not covered by many civil service protections." (4) Robert Lamphere first assignment was in Birmingham, Alabama. It was FBI policy at the time to send new agents to a field office as far away as possible from the site of their upbringing. Most of his cases were linked to America's entry into the Second World War: "I investigated a supposed murder at a new defence plant in Huntsville. I went along on a raid of a series of brothels near an army base in Tennessee. I took part in searches of the homes of enemy aliens (they were proscribed from owning such things as shortwave radios, guns and telescopes). I helped look into suspected sabotage in coastal dockyards." (5) In 1942 Robert Lamphere was transferred to the New York City office. Over the next three years he concentrated on investigating Soviet agents. He became a member of a team of about fifty agents. Lamphere read up the reports on the FBI previous investigations into Soviet espionage. He discovered that Gaik Ovakimyan had been head of the NKVD activities in the United States between 1933 and 1941. (6) Ovakimian main contact was Jacob Golos. He ran agents that included Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, William Remington, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Elizabeth Bentley, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Joseph Katz, William Ludwig Ullmann, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Abraham Brothman, Mary Price, Cedric Belfrage and Lauchlin Currie. Golos ran a travel agency, World Tourists in New York City. The FBI was aware that it was a front for Soviet clandestine work and his office was raided by officials of the Justice Department. (7) Some of these documents showed that Earl Browder, the leader of the Communist Party of the United States, had travelled on a false passport. Browder was arrested and Golos told Elizabeth Bentley: "Earl is my friend. It is my carelessness that is going to send him to jail." Bentley later recalled that the incident took its toll on Golos: "His red hair was becoming grayer and sparser, his blue eyes seemed to have no more fire in them, his face became habitually white and taut." (8) According to Bentley, United States officials agreed to drop the whole investigation, if Golos pleaded guilty. He told her that Moscow insisted that he went along with the deal. "I never thought that I would live to see the day when I would have to plead guilty in a bourgeois court." He complained that they had forced him to become a "sacrificial goat". On 15th March, 1940, Golos received a $500 fine and placed on four months probation. (9) Robert J. Lamphere pointed out: "Ovakimian was known to be in close contact with Jacob Golos, the head of World Tourist, Inc., a Communist-dominated organization in New York. In May 1941, the FBI closed in on Ovakimian and arrested him; he was charged with being a foreign agent who had not registered as such with the Department of Justice." (10) Ovakimian was not covered by diplomatic immunity and had to appear before a judge, who had set bail at $25,000, while he continued to live in New York City awaiting trial. (11) Lamphere claims that as the FBI had been watching Ovakimian and Golos for sometime, they expected to make further arrests: "At that point the Bureau had identified a number of his agents, and might possibly have rolled up several of his networks - including Golos and other people at World Tourist - but international considerations intervened. The State Department knew that a half-dozen Americans were being detained in Russia, and struck a deal whereby they would be exchanged for Ovakimian." (12) It has been claimed by Soviet agent, Alexander Feklisso, that in June 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered that the charges be dropped and Ovakimian was allowed to leave the country. (13) Robert Lamphere pointed out in The FBI-KGB War (1986): "Ovakimian might well have laughed at us over that one, for by the time of his deportation Germany had attacked its former ally, Russia, and several of the Americans in the deal were captured by the advancing Third Reich and never reached the United States. As I recall, none of the Americans in Russian hands had been spies, and in any event, the Russians welched on other parts of the deal and did not return to us the Americans whom the Germans missed. The whole affair was a mess, and my colleagues in New York who handled the case were thoroughly disgusted with the State Department over it. Later, reading over the 164-page summary report on Ovakimian, I was impressed by how much the FBI had been able to find out about the man - and was depressed by the fact that we had been forced to let him go." (14) By the time Robert Lamphere had joined the Soviet Espionage unit of the FBI, Vassili Zarubin, was NKVD's most senior agent in the United States. Zarubin and his wife, Elizabeth Zarubina arrived in the autumn of 1941. Christopher Andrew argues: "Vassily Zarubin (alias Zubilin, codenamed MAKSIM) was appointed legal resident in New York. Already deeply suspicious of British commitment to the defeat of Nazi Germany, Stalin also had doubts about American resolve. He summoned Zarubin before his departure and told him that his main assignment in the United States was to watch out for attempts by Roosevelt and 'US ruling circles' to negotiate with Hitler and sign a separate peace. As resident in New York, based in the Soviet consulate, Zarubin was also responsible for sub-residencies in Washington, San Francisco and Latin America." (15) Lamphere admits that the FBI were not very effective in dealing with Zarubin. His "name cropped up in a number of cases, and during my time in New York we charted his comings and goings and tailed him when the manpower was available. We tried to learn what he was doing; most of the time we didn't know." As well as being active in New York City he made regular visits to San Francisco and Hollywood. In 1943, Zarubin was appointed as third secretary of the Russian embassy in Washington. (If you are enjoying this article, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter and Google+ or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.) On 7th August, 1943, J. Edgar Hoover received an anonymous letter naming Vassili Zarubin, Elizabeth Zarubina, Semyon Semyonov, Leonid Kvasnikov and seven other NKVD agents working in the United States. This included Soviet officials, Vassili Mironov and Vassili Dolgov, and consular officials Pavel Klarin (New York) and Gregory Kheifets (San Francisco). (16) The letter also accused Zarubin of being a Japanese agent and his wife was working for Nazi Germany. Zarubin was also accused of being involved in Katyn Forest Massacre and was "interrogated and shot Poles in Kozelsk, Mironov in Starobelsk". The writer went on to describe a large network of Soviet agents, "among whom are many U.S. citizens". He named Earl Browder and Boris Morros. He also claimed that a "high-level agent in the White House" (this was probably Lauchlin Currie). Zarubin continued to work in Washington. In early 1944 it was reported that he had lost his temper at an official dinner and upset important guests. Soon afterwards a NKVD Personnel Directorate reported that his period in charge had been marked by a series of blunders, including calling his agents by their codename in front of American government officials. That summer, one of NKVD's agents, Vassili Mironov, contacted Joseph Stalin and accused Zarubin of being in secret contact with the FBI. (17) In August 1944, Zarubin, his wife, Elizabeth Zarubina, and Mironov, were recalled to Moscow and he was replaced by Anatoly Gorsky. Mironov's allegations against Zarubin were investigated and found to be groundless and he was arrested for slander. However, at his trial Mironov was found to be schizophrenic. (18) According to Pavel Sudoplatov, the author of Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness (1994), the letter sent to the FBI had been written by Mironov. (19) In September 1945, William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination, was told that Igor Gouzenko, a cipher clerk in the Russian Legation in Ottawa, Canada, wanted to defect. Gouzenko later wrote: "During my residence in Canada, I have seen how the Canadian people and their government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean - and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back to Canada - all this without the knowledge of the Russian people." (20) Stephenson arranged for Gouzenko to be taken into protective custody. He was then transfered to Camp X, where he and his wife lived in guarded seculusion. Later two former BSC agents interviewed him. Gouzenko provided evidence that led to the arrest of 22 local agents and 15 Soviet spies in Canada. Information from Gouzenko also resulted in the arrest and conviction of Klaus Fuchs and Allan Nunn May. Gouzenko also claimed that there was a Soviet agent inside MI5. However, he was later to argue that Roger Hollis showed little interest in this evidence. "The mistake in my opinion in dealing with this matter was that the task of finding the agent was given to MI5 itself. The results even beforehand could be expected to be nil." According to Robert Lamphere information provided by Gouzenko suggested that Ignacy Witczak, a teacher who worked at the University of Southern California, had set up clandestine Soviet networks along the West Coast. The FBI followed Witczak for several months. However, just before they planned to arrest him, Witczak managed to disappear. Lamphere believes that he went back to the Soviet Union on a Russian ship. (21) Elizabeth Bentley had a meeting with the FBI on the 7th November 1945. At this meeting she signed a 107 page statement that named Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, William Remington, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Joseph Katz, William Ludwig Ullmann, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Abraham Brothman, Mary Price, Cedric Belfrage and Lauchlin Currie as Soviet spies. The following day J. Edgar Hoover, sent a message to Harry S. Truman confirming that an espionage ring was operating in the United States government. (22) Some of these people, including White, Currie, Bachrach, Witt and Wadleigh, were named by Whittaker Chambers in 1939. (23) As a result of Bentley's testimony the FBI returned to interview Whittaker Chambers: "From 1946 through 1948, special agents of the F.B.I., too, were frequent visitors. Usually, they were seeking information about specific individuals. For some time they were much interested in Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Dr. Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, John Abt and others. At that time, I had no way of knowing that they were checking a story much more timely than mine - that of Elizabeth Bentley. Most of these investigators went about their work in a kind of dogged frustration, overwhelmed by the vastness of the conspiracy, which they could see all around them, and depressed by the apathy of the country and the almost total absence in high places of any desire to root out Communism." (24) J. Edgar Hoover attempted to keep Bentley's defection a secret. The plan was for her to "burrow-back" into the Soviet underground in America in order to get evidence against dozens of spies. However, it was Hoover's decision to tell William Stephenson, the head of head of British Security Coordination about Bentley, that resulted in the Soviets becoming aware of her defection. Stephenson told Kim Philby and on 20th November, 1945, he informed NKVD of her betrayal. (25) On 23rd November, Moscow sent a message to all station chiefs to "cease immediately their connection with all persons known to Bentley in our work and to warn the agents about Bentley's betrayal". The cable to Anatoly Gorsky told him to cease meeting with Donald Maclean, Victor Perlo, Charles Kramer and Lauchlin Currie. Another agent, Iskhak Akhmerov, was told not the meet with any sources connected to Bentley. (26) Robert Lamphere was not involved in the original investigation but eventually was "put in charge of the voluminous Bentley files and came to know them intimately". "Bentley had named more than eighty individuals as Soviet sources or agents, and said that a dozen different government agencies or government-associated groups had had their information stolen and delivered by her to the KGB. Because of the importance of her charges, Director Hoover had felt duty-bound to alert the White House, Cabinet officers and other top officials of her main accusations. But in the process of spreading Bentley's information throughout the upper echelons of the government, many of those whom Bentley had named learned of the accusations and had a chance to cease any questionable activities." Lamphere admitted: "The problem was that, unlike Gouzenko, who brought out evidence in the form of telegrams and pages from Zabotin's diary, Bentley had nothing to backstop her stories - no documents, no microfilm, not even a gift of Russian origin which might have been traced. So very little in the way of prosecutions could be mounted, based on her recollections. Privately, some of us were exasperated and thought we knew what could and should have been done with Bentley. I believe that very early the FBI could have forced things by moving in aggressively and interviewing everyone connected with her; in this way we might have gotten some of them to break, or to contradict one another's stories. We also could have obtained warrants and searched the Silvermaster home and the apartments of the Perlo group for evidence. No such actions were taken at the time.... That spring of 1946, after the Bentley affair's initial phase, we in the New York office's Soviet Espionage squad felt frustrated: we were near and yet so far. Igor Gouzenko and Bentley had shown that Russians were operating all around us, but we were unable to counter their efforts." (27) Gerhart Eisler was the chief liaison man between the Communist Party of the United States and the Comintern. Eisler arrived in New York City in 1941. Robert Lamphere was the agent who was given responsibility for Eisler: "Gerhart Eisler, a small, balding, bespectacled man of forty-eight who looked like a bookkeeper. With his young wife, Brunhilda, he lived in a thirty-five-dollar-a-month third-floor walk-up in Long Island City. He spoke with a German accent, as did many of his neighbors, and like many of them also, he had contributed blood during the war. He had also been an air-raid warden... You could set your watch by him. He'd leave his apartment early in the morning and walk in a distinctive, unhurried way to a news-stand, buy the New York Times and catch the IRT subway into Manhattan. To the casual observer he might have seemed ordinary, but on close examination one could notice in his manner a hint of arrogance and a quiet confidence." (28) Eisler spent most of his time meeting with foreign Communists. FBI agents also recorded a conversation between Vassili Zarubin and Steve Nelson, a member of the Communist Party of the United States in California. "Zarubin traveled to California for a secret meeting with Steve Nelson, who ran a secret control commission to seek out informants and spies in the Californian branch of the Communist Party, but failed to find Nelson's home. Only on a second visit did he succeed in delivering the money. On this occasion, however, the meeting was bugged by the FBI which had placed listening devices in Nelson's home." (29) The FBI bug confirmed that Zarubin had "paid a sum of money" to Nelson "for the purpose of placing Communist Party members and Comintern agents in industries engaged in secret war production for the United States Government so that the information could be obtained for transmittal to the Soviet Union." (30) It seems that during the meeting the name of Gerhart Eisler was mentioned. In the summer of 1946 the FBI heard that Gerhart and Brunhilda Eisler planned to leave the country. Robert Lamphere argued: "Many questions were raised by Eisler's answers on the application. He wrote that he'd first entered the country in 1941 - but we knew he'd been here illegally in the 1930s. He swore that he'd never been a Communist; that, too, was a lie. I would have been perfectly happy to have Eisler disappear behind the Iron Curtain. However, I decided not to let him go without a personal interview, an action in line with the more aggressive moves that Emory Gregg and I longed to have the FBI take in such cases. After obtaining permission for an interview, I telephoned Eisler at his apartment in Queens and suggested that it would be a good idea if he came in to see me. When he said he was preparing to leave the United States, I told him I was well aware of his travel plans. Apparently deciding that if he avoided me, the FBI might interfere with his departure, he agreed to come in." (31) Eisler refused to answer some of the questions but it was decided to let him travel to the Soviet Zone of Germany. However, a few days later Louis Budenz, the former managing editor of The Daily Worker, made a speech where he claimed that the "Number One Communist in the US" and the "man who gave theoretical direction to the Party" was a man named "Hans Berger". The FBI was aware that Gerhart Eisler had used the name Hans Berger while in America. It was therefore decided to revoke Eisler's exit visa. Gerhart Eisler gave an interview to Time Magazine: "Gerhart Eisler had nothing to hide. Budenz, he said, as if the explanation were unnecessary to people of intelligence, was obviously mistaken. It was true that he had once been a Communist in Germany but that had been many years ago. He had come to the U.S. in 1941, a poor refugee, hounded by the Nazis. Did he look like a spy? All he wanted to do was go back to Germany, but the U.S. State Department would not allow it." (32) Cedric Belfrage described him as "the professional Austro-German revolutionary, a small man moved to sarcasm or umbrage." (33) Gerhart Eisler appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee on 6th February, 1947. He was accompanied by his attorney Carol Weiss King and a "phalanx of reporters". J. Parnell Thomas, the chairman of the HUAC stated: "Mr. Gerhart Eisler, take the stand." Eisler replied: "That is where you are mistaken. I have to do nothing. A political prisoner has to do nothing." Walter Goodman, the author of The Committee: The Extraordinary Career of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (1964), commented: "He (Eisler) and Thomas yelled at one another for a quarter of an hour without getting anywhere. He was cited for contempt on the spot, and escorted back to his cell on Ellis Island." (34) Louis Budenz told the HUAC that Eisler's role in the Communist Party of the United States was to lay down Comintern discipline to "straying functionaries". However, the most powerful evidence against Eisler came from his sister, Ruth Fischer. She described her brother as "the perfect terrorist type". Fischer had not been on speaking terms with her brother since she was expelled from the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1926 after attacking the policies of Joseph Stalin. (35) She told the HUAC that Eisler had carried out purges in China in 1930 and had been involved in the deaths of numerous comrades, including Nikolay Bukharin. (36) Time Magazine reported: "One of the witnesses who denounced him was his sister, sharp-chinned, black-haired ex-German Communist Ruth Fischer, the person who hates him most. In the beginning, as children of a poverty-stricken Viennese scholar, they had adored each other. Ruth, the older, became a Communist first. Gerhart, who won five decorations as an officer of the Austrian Army in World War I, joined the party in the fevered days of 1918. They worked together. When Ruth, then a bundle of sex appeal and intellectual fire, went to Berlin, Gerhart followed. She became a leader of the German Communist Party, and a member of the Reichstag. But Gerhart took a different ideological tack, began to covet power for himself. He applauded when Ruth was banished from the party by the Stalinist clique." (37) On 18th February, 1947, Richard Nixon made his maiden speech in the House of Representatives on the Gerhart Eisler case. "My maiden speech... was the presentation of a contempt of Congress citation against Gerhart Eisler, who had been identified as the top Communist agent in America. When he refused to testify before the committee, he was held in contempt. I spoke for only ten minutes, describing the background of the case." (38) Nixon concluded the speech with the words: "It is essential as members of this House that we defend vigilantly the fundamental rights of freedom of speech and freedom of speech and freedom of the press. But we must bear in mind that the rights of free speech and free press do not carry with them the right to advocate the destruction of the very government which protects the freedom of an individual to express his views." (39) The only member who voted against the contempt citation was Vito Marcantonio. The trial of Gerhart Eisler opened in July 1947. Louis Budenz once again told of Eisler's inflammatory activities in the 1930s and 1940s. His sister, Ruth Fischer and Hede Massing, his former wife, testified about Eisler's long history as a Communist and Comintern man. Helen R. Bryan, executive secretary of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC), admitted that she had paid Eisler a monthly sum of $150, under the name of Julius Eisman. The FBI also provided information on the false passports that Eisler used in the 1930s. During this evidence Eisler's lawyer, Carol Weiss King, pointed at Robert Lamphere and shouted, "This is all a frame-up by you." (40) Gerhart Eisler's main supporter in the press was Joseph Starobin. He wrote in the The Daily Worker: "This has been more than a trial: it has been the dissection of the rotting tissues of American society today. Here, petty spies and pretentious informers have been manipulated as the puppets of ambitious district attorneys working with the FBI chiefs, who in turn are the bought agents of respectable steel magnates and coal barons." (41) The New Masses reported that Lamphere, the main figure in Eisler's prosecution, was "too pleasant" to the "point of being sinister". In another article Starobin argued: "There are plenty of FBI men in the courtroom here at the trial of Gerhart Eisler. They are easy to spot as they sit on the polished benches and smile in the cool hallways. But the real presence and guiding role of the FBI in this case is very open and unashamed. Alongside the U.S. attorney, William Hitz, there has been sitting all during these weeks the special FBI agent Robert Lamphere, who's had more to do with this fantastic frame-up than any other man. Baby-faced, but hard-lipped, this character has behaved as the government's special counsel, leaning over to prime the prosecutor, fishing into his black bag for papers and notes, and his red neck visibly flushes as the defense counsel unravels the whole abysmal story of what the United States government tried to do with Eisler." (42) On 9th August, 1947, Gerhart Eisler "took the stand, dressed in his shapeless gray suit and blue shirt with its too-large collar." (43) Eisler argued: "I never in my life was a member of the Communist International. I never in my life went anyplace in the whole world as a representative of the Comintern." (44) Eisler denied he was a member of a group that advocated the overthrow of the United States government. He was a member of the German Communist Party (KPD) and this was not one of its policies. After only a few hours of deliberation, the jury brought in a guilty verdict and he was sentenced to a year in prison. Robert Lamphere asked Gerhart Eisler as the court was adjourning, "Gerhart, do you think you got a fair trial?" He replied: "Yes, a fair trial but an unfair indictment. Lamphere later recalled: "It was the last time I saw Eisler in person; in a way, I almost liked him - his bravado was astonishing." (45) The government asked for $100,000 bail, the judge set bail at $23,500. This was put up by supporters of the Communist Party of the United States and Eisler was freed pending appeal. He was tailed by the FBI but in May 1949 he managed to stowaway on the Polish ship Batory. According to Time Magazine, Eisler's lawyer, Carol Weiss King, "almost exploded" when she heard that Eisner had jumped bail, causing the confiscation of the money raised by her friends. The United States asked Great Britain to hold Eisler for extradition and he was arrested in Southampton. Eisler's British lawyers convinced the court that under British law a false oath was not perjury unless it had been taken in connection with a judicial proceeding. Eisler was released and he continued his journey to East Germany. During his investigation of Gerhart Eisler Lamphere interviewed his former wife, Hede Massing. First of all he interviewed her current husband, Paul Massing. Lamphere later recalled: "An economist at a social research institute, Paul was distinguished, erect and completely uncooperative. He believed that the FBI had kept him from becoming a citizen by giving derogatory information on him to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Actually, Paul was right about that, but when the interview was drawing to a close and he had told us nothing of value, this talk of citizenship made me a bit hot under the collar. Standing to leave, I said with some vehemence that becoming a citizen was a privilege, not a right, and that Paul had lived safe and secure in the United States during the war, whereas if he'd stayed in Germany the Nazis would long since have killed him." (46) Paul talked to Hede Massing about this experience: "Paul and I thought the problem out, slowly, carefully. We decided to tell our story. Two polite efficient men asked me for some specific information regarding Gerhart Eisler. They not only understood and respected my rights, but made it clear that my co-operation was purely voluntary. There was no coercion, no tricks; they had a job to do and they thought that I could be of help if I cared to. It was entirely up to me whether I did. They were intelligent, observant, well-informed - as I could judge by the questions asked - and pleasantly unemotional. They did not underestimate the individual under suspicion, on the contrary, they seemed to respect him and understand him in his own environment. This impressed me indeed. It was most unexpected. The two agents, to whom I spoke the first few times, were Lamphere and a kindly, graying, middle-aged man, whose name was Hugh Finzel." (47) Robert Lamphere later wrote about his impressions of Hede Massing in his book, The FBI-KGB War (1986): "A tall, middle-aged, carefully dressed woman, no longer the striking beauty she had obviously been in her youth, Hede was still attractive... Languishing in Berlin, Hede had dinner with Richard Sorge, who later became one of the most successful Communist spies of the era. Sorge, formerly a Comintern man like Gerhart, had spirited his wife away from an older man, just as Paul had taken Hede from Julian. At dinner he convinced Hede that espionage was heroic and glamorous and that she, too, could do important things for the Party. He took her to meet 'Ludwig,' a man she discovered she already knew as a regular customer of the Gumperz bookstore, where she had worked for a time. Ludwig... was sometimes known as Ignace Reiss, a charming, erudite man who inspired near-fanatic loyalty on the part of Hede and many other agents. Together with his childhood friend Walter Krivitsky, Ludwig was a mainstay of Russian intelligence and had been so since the early 1920s. On his instructions Hede dropped her attendance at local Party meetings, provided details and evaluations of promising prospects, located 'safe' apartments for agents and set up 'mail drops' where messages could be exchanged - in short, she learned the rudiments of courier work." (48) Massing told Lamphere that she joined a spy network that included Vassili Zarubin, Boris Bazarov, Elizabeth Zarubina, Joszef Peter, Earl Browder and Noel Field. However, she decided not to tell the FBI about Laurence Duggan and Alger Hiss. "The two most important names I did not mention in my confidential sessions with the FBI were Larry Duggan and Alger Hiss.... I was absolutely convinced that Duggan had left the organization, if, indeed, he had ever belonged to it at all. Alger Hiss had not worked with me, the relationship was a fleeting one, important only in connection with Noel Field. But more than that, he, too, I was convinced, must have broken with whatever his organization might have been. I had watched his career with great interest." (49) Massing did change her mind and eventually gave evidence against Hiss in his perjury trial in November 1949. After the war Meredith Gardner was assigned to help decode a backlog of communications between Moscow and its foreign missions. By 1945, over 200,000 messages had been transcribed and now a team of cryptanalysts attempted to decrypt them. The project, named Venona (a word which appropriately, has no meaning), was based at Arlington Hall, Virginia. Soviet messages were produced in exactly the same way as Japanese super-enciphered codes. However, "where the Japanese gave the codebreakers a way in by repeatedly using the same sequences of additive, the Russian system did not. As its name suggests, the additive appeared on separate sheets of a pad. Once a stream of additive had been used, that sheet was torn off and destroyed, making the message impossible to break." (50) According to Peter Wright, the author of Spymaster (1987): "Meredith Gardner... began work on the charred remains of a Russian codebook found on a battlefield in Finland. Although it was incomplete, the codebook did have the groups for some of the most common instructions in radio messages - those for 'Spell' and 'Endspell.' These are common because any codebook has only a finite vocabulary, and where an addresser lacks the relevant group in the codebook - always the case, for instance, with names - he has to spell the word out letter by letter, prefixing with the word 'Spell,' and ending with the word 'Endspell' to alert his addressee. Using these common groups Gardner checked back on previous Russian radio traffic, and realized that there were duplications across some channels, indicating that the same one-time pads had been used. Slowly he 'matched' the traffic which had been enciphered using the same pads, and began to try to break it." (51) As David C. Martin pointed out it was slow work: "When the cryptanalysts discovered that the same series of additives had been used more than once, they had all the leverage they needed to break the Soviet cipher system. Having used guesswork to deduce the additives for a Soviet message intercepted in one part of the world, they could test those same additives against the massive backlog of messages intercepted in other parts of the world. Sooner or later the same additives would appear and another message could be deciphered. It was an excruciatingly tedious task with less than perfect results. Since only a portion of the code book had been salvaged, many of the 999 five-digit groups used by the Soviets were missing. Knowing the additive might yield the proper five-digit group, but if that group could not be found in the code book, the word remained indecipherable. Whole passages were blanks, and the meaning of other phrases could be only vaguely grasped." (52) It was not until 1949 that Meredith Gardner made his big breakthrough. He was able to decipher enough of a Soviet message to identify it as the text of a 1945 telegram from Winston Churchill to Harry S. Truman. Checking the message against a complete copy of the telegram provided by the British Embassy, the cryptanalysts confirmed beyond doubt that during the war the Soviets had a spy who had access to secret communication between the president of the United States and the prime minister of Britain. The Armed Forces Security Agency requested copies of all transmissions handled by the British Embassy and began matching them against the encoded messages in the New York-to-Moscow channel, working backward through the code book and arriving at the additive. Gradually they were able to transcribe these messages. It now became clear that there had been a massive hemorrhaging of secrets from both the British Embassy in Washington and the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Robert Lamphere was assigned to work closely with Meredith Gardner as he probably knew more about Soviet spies than anyone else in the FBI. He therefore worked closely with Meredith Gardner and together they were able to catch several Soviet spies. "The ASA offices were at Arlington Hall, across the Potomac from the District of Columbia, in Virginia, at what used to be a girls' school. Gardner met me in one of the brick-and-wood-frame buildings, and as we sat down to talk I soon realized that Rowlett's description of him was accurate. Gardner was tall, gangling, reserved, obviously intelligent, and extremely reluctant to discuss much about his work or whether it would progress any distance beyond the first fragments that the FBI had already received. I asked him how I could be of assistance to him; he seemed not to know. I told him I was intensely interested in what he was doing and would be willing to mount any sort of research effort to provide him with more information; he simply nodded. I offered to write up a memo about one of the message fragments because I thought the FBI might have a glimmer of understanding of the subject matter being discussed by the KGB; he was noncommittal." Lamphere recorded in his autobiography, The FBI-KGB War (1986): "From that day on, every two or three weeks I would make the pilgrimage out to Arlington Hall. Meredith Gardner was indeed not easy to know, and was extremely modest about his work, but eventually we did become friends. Neither the friendship nor the solution to the messages was achieved overnight, but steady progress was made. Little by little he chipped away at the messages, and I helped him with memoranda that described what the KGB might be referring to in some of them. The ASA's work was further aided by one of the early, rudimentary computers." (53) In the spring of 1948 the work of Meredith Gardner began to pay dividends. All Soviet agents in the United States used codenames. However, if someone was not a spy their real name would be used. For example, Gardner was able to translate this message from Stepan Apresyan to NKVD headquarters on 26th July 1944: "In July ANTENNA was sent by the firm for ten days to work in CARTHAGE. There he visited his school friend Max Elitcher, who works in the Bureau of Standards as head of the fire control section for warships... He has access to extremely valuable materials on guns... He is a FELLOWCOUNTRYMAN... By ANTENNA he is characterized as a loyal, reliable, level-headed and able man. Married, his wife is a FELLOWCOUNTRYMAN. She is a psychiatrist by profession, she works at the War Department. Max Elitcher is an excellent amateur photographer and has all the necessary equipment for taking photographs. Please check Elitcher and communicate your consent to his clearance." (54) Meredith Gardner knew what two of the codenames meant CARTHAGE (Washington) and FELLOWCOUNTRYMAN (Communist Party of the United States). They were also able to identify Max Elitcher who worked at the Navy Bureau of Ordnance in Washington in July 1944. In fact, the Office of Naval Intelligence had questioned Elitcher and his close friend, Morton Sobell, about their attendance at a American Peace Mobilization Committee meeting in January 1941. Further investigations showed that Elitcher and Sobell had contact with other former left-wing activists, Alfred Sarant, Julius Rosenberg, Joel Barr and Vivian Glassman. Another message sent on 4th June, 1948, said that ANTENNA's wife's name was Ethel. "Christian name, Ethel, used her husband's last name; had been married for five years (at this time); 29 years of age; member of the Communist Party, USA, possibly joining in 1938; probably knew about her husband's work with the Soviets." It was not long before the FBI discovered that Julius was married to Ethel Rosenberg (born 1915 and married 1939). Max Elitcher was interviewed by the FBI and he admitted that both Morton Sobell and Julius Rosenberg had asked him to obtain secret information from the Navy Bureau of Ordnance. He claimed that in July 1948, Max and Helen Elitcher stayed with Sobell and his wife in Flushing, while house hunting. One night Elitcher drove Sobell when he delivered a "35-millimeter film can" to Julius Rosenberg who was living in Knickerbocker Village. On the way back Sobell told him that Rosenberg had discussed Elizabeth Bentley, who had already confessed to being a Soviet spy. The trial of Sobell, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg began on 6th March 1951. The first witness of the prosecution was Max Elitcher. Irving Saypol asked him whether Julius Rosenberg visited him in 1944 in Washington: "Yes, he called me and reminded me of our school friendship and came to my home. After a while, he asked if my wife would leave the room, that he wanted to talk to me in private. She did. Then he began talking about the job that the Soviet Union was doing in the war effort and how at present a good deal of military information was being denied them by some interests in the United States, and because of that their effort was being impeded. He said there were many people who were implementing aid to the Soviet Union by providing classified information about military equipment, and so forth, and asked whether in my capacity at the Bureau of Ordnance working on anti-aircraft devices, and computer control of firing missiles, would I turn information over to him? He told me that any information I gave him would be taken to New York, processed photographically and would be returned overnight - so it would not be missed. The process would be safe as far as I am concerned." (55) In his summing up Judge Irving Kaufman was considered by many to have been highly subjective: "Judge Kaufman tied the crimes the Rosenbergs were being accused of to their ideas and the fact that they were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. He stated that they had given the atomic bomb to the Russians, which had triggered Communist aggression in Korea resulting in over 50,000 American casualties. He added that, because of their treason, the Soviet Union was threatening America with an atomic attack and this made it necessary for the United States to spend enormous amounts of money to build underground bomb shelters." (56) The jury found all three defendants guilty. Thanking the jurors, Judge Kaufman, told them: "My own opinion is that your verdict is a correct verdict... The thought that citizens of our country would lend themselves to the destruction of their own country by the most destructive weapons known to man is so shocking that I can't find words to describe this loathsome offense." (57) Judge Kaufman sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the death penalty and Morton Sobell to thirty years in prison. Lamphere and Meredith Gardner were both opposed to the execution of Ethel Rosenberg. As Gardner pointed out, the fact that Ethel was named in the secret messages, showed that she was not a Soviet spy. (58) In his autobiography, The FBI-KGB War (1986), Robert Lamphere admitted that the main reason Ethel Rosenberg was arrested is that they thought it would make Julius confess: "Al Belmont had gone up to Sing Sing to be available if either or both of the Rosenbergs should decide to save themselves by confessing, and to be on hand as the expert if the question should arise whether or not a last-minute confession was actually furnishing substantial information on espionage. I was sitting in Mickey Ladd's office, with several other people; we had an open telephone line to Belmont in Sing Sing, and as the final minutes came closer, the tension mounted. I wanted very much for the Rosenbergs to confess - we all did - but I was fairly well convinced by this time that they wished to become martyrs, and that the KGB knew damned well that the U.S.S.R. would be better off if their lips were sealed tight. Belmont telephoned us to say that the Rosenbergs had refused for the last time to save themselves by confession. Julius was reported dead to us at 8:05 P.M., and Ethel at 8:15 P.M." (59) Evidence emerged in December 1948 that suggested Judith Coplon, who worked for the Justice Department, was a Soviet spy. Robert Lamphere pointed out: "Coplon's case had to be handled with the utmost care, because her position at justice was a difficult one for us. The FBI had always felt relatively secure from Soviet penetration, but here was Coplon, as a political analyst in the Foreign Agents Registration (FAR) section of Justice, who also worked on some 'internal security' matters in which sensitive FBI reports were continually on her desk or within easy reach. That meant the agency most compromised by her was the FBI. Coplon routinely handled some Bureau materials that had to do with the Soviets. While the most sensitive stuff such as that dealing with our breakthrough in the KGB's communications - never went near her, what she did see on a regular basis was damaging enough. (60) FBI officials obtained the authorization of Tom C. Clark, the Attorney General, to wiretap Coplon's office and home phones. She was also followed in the hope that they would be able to identify her Soviet contacts and other members of the spy network. In January 1949 FBI agents discovered that she was meeting Valentin Gubitchev, a Soviet employee on the United Nations staff. They decided to set a trap by creating a memorandum "that contained enough truth to make it seem important and enough false information to make it imperative for Coplon to grab it and quickly deliver it to her Soviet contact." (61) As Hayden B. Peake has pointed out: "After surveillance established that she was in regular contact with an NKGB officer in New York City, the FBI planned to arrest them when she passed classified documents to him. However, two problems arose. First, at the time of arrest, she had not passed the documents, although they were in her possession. Second, she was arrested without a warrant, although the FBI had had plenty of time to get one. These details would figure significantly in her appeals." (62) Judith Coplon was arrested on 4th March, 1949 in Manhattan as she met with Valentin Gubitchev. They discovered that she had in her handbag twenty-eight FBI memoranda. This included details of the intensive monitoring of individuals such as David K. Niles, Frederic March, Edward G. Robinson and Edward Condon, who were all supporting Henry Wallace in his 1948 Presidential Campaign. Judith Coplon was charged with espionage. At her trial that began on 25th April 1949 Coplon claimed "she was meeting Gubitchev because they were in love and was not planning to give him the documents. But he was married, and prosecutors brought out that she had spent nights in hotels with another man at about the same time." (63) Coplon was helped in her defence by the decision of Judge Albert Reeves to rule that in order to convict her on the charge of unauthorized possession of classified documents, government prosecutors must produce in open court the originals of the FBI documents found in her handbag at the time of her arrest. During the trial, Coplon's lawyer, Archie Palmer, argued that the evidence from the confidential informant was in fact from illegal telephone taps. Then, over the strenuous objections of the FBI, he succeeded in getting raw FBI data collected on many famous people admitted as evidence, although they had nothing to do with the case. This included Paul Robeson, Dalton Trumbo, Frederick March, Helen Hayes, Danny Kaye, and Edward G. Robinson. At the end of her trial Coplon was found guilty of espionage. Judith Coplon claimed: "I'm innocent of all charges. I'm a victim of a horrible, horrible frame-up." Next day, before the judge pronounced sentence, Judith CopIon had her final say. She had not received a fair trial, she insisted. "I understand that I can plead for mercy. That I, will not do, because pleading for mercy would mean an admission of guilt and... I am innocent." Judge Reeves handed down his sentence: 40 months to ten years on the first count; one to three years on the second; sentences to be served concurrently, i.e., a maximum of ten years. (64) The following year Coplon and Valentin Gubitchev were charged with conspiracy. As Hayden B. Peake has pointed out: "The alleged telephone taps became a major element in the second trial in New York, when Coplon and her case officer, Gubitchev, were convicted together. During the first trial, FBI special agents had denied direct knowledge of the taps. At the second, however, one of them admitted that taps had been used to collect evidence presented at trial. Later, the authors found a memorandum acknowledging the recordings and indicating that they had been intentionally destroyed to avoid having to reveal their existence." (65) Both Coplon were found guilty and Gubitchev was deported. However, Coplon appealed against both convictions. "The appellant judge in New York concluded that it was clear from the evidence that she was guilty, but the FBI had lied under oath about the bugging. Moreover, he wrote, the failure to get a warrant was not justified. He overturned the verdict, but the indictment was not dismissed. In the appeal of the Washington trial, the verdict was upheld, but, because of the possible bugging, a new trial became possible." (66) The case caused considerable embarrassment to the FBI. As Athan Theoharis, the author of Chasing Spies (2002) has pointed out : "Their public release confirmed that FBI agents intensively monitored political activities and wire-tapped extensively - with the subjects of their interest ranging from New Deal liberals to critics of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, and with information in fifteen of the twenty-eight reports coming from wiretaps. And because Coplon's own phone had been wiretapped, her conviction was later reversed on appeal. The appeals judge concluded that FBI wiretapping had possibly tainted Coplon's indictment, under the Supreme Court's 1937 and 1939 rulings in Narclone v. U.S., requiring the dismissal of any case based on illegal wiretaps." (67) Robert Lamphere left the FBI in 1955. He took a post in the Veterans Administration dealing with investigations, security and internal auditing. Lamphere later recalled: "Within five years I had risen through the executive ranks to deputy administrator, the number two position in the agency. In 1961... I resigned from the VA and became an officer of one of the country's largest insurance companies." (68) According to the The New York Times this was the John Hancock Mutual Insurance Company (69). Robert Lamphere died of prostate cancer in a Tucson hospital on 7th January, 2002.Robert Lamphere - FBI Agent

Gaik Ovakimyan

Vassili Zarubin

Igor Gouzenko

Elizabeth Bentley

Gerhart Eisler

Hede Massing

The Venona Project

The Julius Rosenberg Network

Judith Coplon

Post FBI

Primary Sources

(1) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986)

I was born in 1918 in the Coeur d'Alene mining district of Idaho, the middle child of three, and grew up in the small town of Mullan, where my father had become a Teaser. This was a man who leased the rights to mine someone else's underground ore deposits - silver, lead and zinc in this area - and who hired hands to do the actual work. Many times before, my father had risen to the position of shift boss, but his temper got in the way of further advancement; being a Teaser, in control of his own operation, was more suited to his personality. In later years he also became a consultant to companies that had financial interests in ores and deposits.

Mullan was a tough little town. The inhabitants came from a variety of national backgrounds; the predominant group was composed of Finns. Most of us boys learned a few choice swearwords in Finnish, and I grew up with tough kids (though I never considered myself one of them) and had my share of fights. A little professional boxing instruction helped me in those tiffs. My father and mother expected all three of us to do well in school, and we did. I liked nothing better than to go up into the hills with my dog and wander about on the ridge-line, out of sight of people from dawn to dusk. I learned to hunt, to fish and to enjoy reading.

The University of Idaho counselor tried to talk me out of an accelerated program that would bypass the usual bachelor's degree and earn me a law degree in five years, but I stubbornly pointed out that it was listed in the catalogue and that I was going to do it. To help defray the expenses, during the summer I worked in the mines. The first time, my father made sure I got every dirty job available so he wouldn't appear to be playing favorites; succeeding summers, I worked deeper in the mines, and for the larger company that owned them. I preferred working down in the hole because I was treated more as an equal. The air was stale, hot and humid, and we twisted the sweat out of our socks when we got home at night. In the depths there were more fights. Twice I had to face down other men; I didn't like that, but my father heard of one of the incidents and it seemed to impress him. The other miners started to cajole me into joining the union until they realized they didn't want a boss's son at their meetings.

Tough situations in the mines were counterpoint to the intellectual jousting at the university. From both I learned the importance of talking to people on whatever level they were functioning, an insight that stood me in good stead in later years.

(2) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986)

Eight years of the New Deal had brought considerable amplification of the federal government's role in the country, but before World War II began for the United States, Washington was still a somewhat sleepy southern city. In 1939 President Franklin D. Roosevelt had given FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover jurisdiction over all espionage matters, and the FBI had begun to expand at a rapid rate. The Bureau was looking for candidates, and I was seeking experi¬ence. I reasoned I'd stay in the FBI for two years and then, with practical knowledge under my belt, I'd be better able to open up my own law office or go into a business.

The FBI was known as an elite outfit. At a time when most adults had never gone to college, FBI men had graduate degrees; they were taller than the norm (over five foot seven); and they were exemplars of good upbringing and high moral standards. If I was somewhat attracted to the FBI's "crime-busting" image, I was more attuned to the idea of being among the very best, and wanted to measure up to the high requirements for membership in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. My parents were dead, my hometown was left behind, and for me, the past was rapidly receding. Maybe I needed the structure the Bureau would provide, and perhaps I just sought a way to test myself. Either way, the FBI was a good choice.

To be admitted to the class of new agents one had to pass a written exam, be recommended after an interview by an experienced Bureau official, and survive an extensive background check. Later on, when I conducted such "new applicant" checks, I understood how thoroughly the FBI evaluated the family, schooling, experience and moral fiber of those who wished to carry one of the Bureau's gold badges.

Fifty of us began classes in Washington, D.C. I was the youngest, and more than a bit brash. Instructors told us 10 to 20 percent of the class would wash out. We were issued what was repeatedly described as "Bureau property" - credentials, badge, two briefcases (one with a secure lock), various manuals, and a.38 pistol. Only God would be able to help us if we lost this Bureau property. One morning we were given exactly sixty minutes in which to buy a Western-style belt to hold up our holster, a snap-brim hat, several white shirts and other appurtenances of the well-dressed FBI agent. During this time we were also to pack for our trip to Quantico, Virginia, and eat lunch. Along with most of the other novices, I managed this trick somehow. In his haste, one guy left his Bureau-property briefcase in a taxi, and was crucified for the blunder.

At the FBI training center on the Marine base at Quantico, we began intensive study-classes were from 9:00 A.M. to 9:00 P.M. Monday through Saturday, with a half-day on Sunday. I believe the FBI packed more into sixteen weeks than a college offered in a year. And unlike most boot-camp experiences, the Quantico program was directly relevant to our later work in the field.

If the training was superb, it was also purposely difficult. After only two or three of us passed the first exam, we were told that we were the dumbest bunch ever to be allowed near a gold badge, but that because so many of us had failed, there'd be a makeup exam on Monday. We crammed all weekend, only to find the Monday test was easier than the one we'd failed; the first one had been a deliberate move to scare the hell out of us.

Two ideas were continually drummed into us: pride at membership in an elite organization, and fear of failure. Eventually these two became completely intertwined and inseparable feelings. Inculcation of fear began on our first day, and dread of our superiors' wrath never let up during my whole career in the FBI. We were constantly afraid of earning the displeasure of Hoover - who, we learned, could fire any of us at any time for any infraction of the multitudinous rules that governed the conduct of an FBI man, on or off the job. Unlike other government employees, we in the FBI were not covered by many civil service protections.

We were expected to be better in every category than ordinary lawmen. We knew more about firearms. We knew how to behave in the courtroom - to stand erect to take the oath, to testify impartially as to the facts in simple language cleansed of legalisms that might confuse the jury and in a voice loud enough so that all might be able to hear. It was to be "Yes, sir," and "No, sir," to all citizens, regardless of their station. To a much greater degree than most policemen and many prosecutors, we knew and continually reviewed the wording, intent and details of all the statutes the FBI had in its purview.

(3) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986)

Espionage and underground networks were ingrained in the character of the Soviet regime, it seemed. For years prior to the 1917 revolution the leaders operated secretly; once the Bolsheviks seized power they made espionage and a secret police force important elements in their own government. This force shifted names many times, from the OGPU to the NKVD, the NKGB, and the MGB before it became the KGB; through all the nomenclature changes it retained the same dread character while its power increased until it was a dominating force in Russian society. By the i94os the organization encompassed border guards, railroad police and forest patrolmen as well as men who peered over the shoulders of Russians inside the country and those who spied on foreign countries. The KGB became the entity closest to what George Orwell described in 1984 as the "thought police." It was believed to have massive dossiers on Russian citizens and on all members of foreign Communist Parties. It controlled the "Gulag archipelago" and the whole of Siberia. Its functions included and went far beyond those performed inside the United States by the FBI, Immigration Service, Customs Department, border patrols and the National Guard, and outside the United States by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The KGB virtually controlled the embassies as well as the various trading corporations, press service offices and other Soviet links to the outside world. It was known to have an experienced assassination division.

In the late 1940s we in the FBI had only partial glimpses of what later arrests and defections would document about the KGB. But we knew even then that there were KGB rings operating inside Germany, Switzerland, France, Holland, Belgium, Sweden, England, Australia, Canada and the United States just to cite cases that have subsequently been made public. Consider the example of Sweden: all during the 1940s five KGB networks there worked to pass to the U.S.S.R. every single detail of Sweden's national defenses. When some of the spies were caught, it was learned that the Soviets also had saboteurs and explosives hidden inside Sweden, and in case war broke out between the two countries, the Soviets could have immediately knocked out the Swedish railroads and communications facilities to gain a decided advantage in the conflict.

Gradually, in my mind, the image of an amorphous, omnipotent KGB began to resolve into that of a dangerous adversary that operated with specific human beings as agents-some of whom had brushed very close to the FBI. In a later period there were 400,000 employees and 90,000 officers of the KGB worldwide, but most were concentrated inside Russia. As might be imagined, only the most trusted and experienced officers were sent to such sensitive areas as the United States.

It seemed clear from our files that much of the KGB's espionage in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s could be traced to two Soviet "residents," Vassili Zubilin and Gaik Ovakimian. When I was a young agent, I read up on them, and later - indeed, throughout my whole career in the FBI-I spent my time chasing after their handiwork. These men became something like totems for me, symbols of the adversary whom we were forever trying to locate and eliminate. Although they were people of the shadows, they were not faceless; I learned their faces, and tried to discern what I could about their characters.

The one who troubled me most was Gaik Badalovich Ovakimian, whom the FBI had pinpointed as head of the KGB's activities in the United States from 1933 to 1941. He had vanished before I even came into the game, but for many years I tracked the agents he had put into place. He was often referred to as "the wily Armenian," and it was a measure of his slipperiness that it was never completely clear whether or not he really was an Armenian.

The official documents showed that Ovakimian was born on August 11, 1898, in Russia. Rather small and stocky - five foot seven, 165 pounds - he had a medium-dark complexion with dark-brown hair and blue eyes. He was educated as an engineer, and spoke somewhat broken English as well as German, French and Russian. He was married to a woman named Vera, and they had a daughter, Egina. In the 1930s the FBI had uncovered an extensive industrial espionage operation tied to a man named Armand Labis Feldman, who was connected to Ovakimian. Then his name cropped up in conjunction with a case that originated in England with a man who had a false passport in the name of Willy Brandes.

As we later learned, Ovakimian's recruits were scattered as far afield as Mexico and Canada; some of his exploits involved forged passports and attempts on Leon Trotsky's life while the former Soviet leader was in exile in Mexico. Americans whom Ovakimian recruited or controlled described him as charming, serious, sympathetic, well read in English literature, knowledgeable in science, and a man who inspired loyalty in his agents. He must also have been agile and politically aware, for he survived the great purges of the late 1930s which decimated the upper ranks of the Russian espionage services.

Ovakimian was known to be in close contact with Jacob Golos, the head of World Tourist, Inc., a Communist-dominated organization in New York. In May 1941, the FBI closed in on Ovakimian and arrested him; he was charged with being a foreign agent who had not registered as such with the Department of Justice. At that point the Bureau had identified a number of his agents, and might possibly have rolled up several of his networks - including Golos and other people at World Tourist - but international considerations intervened. The State Department knew that a half-dozen Americans were being detained in Russia, and struck a deal whereby they would be exchanged for Ovakimian. As a result, the KGB man was allowed to leave the United States in July 1941.

Ovakimian might well have laughed at us over that one, for by the time of his deportation Germany had attacked its former ally, Russia, and several of the Americans in the deal were captured by the advancing Third Reich and never reached the United States. As I recall, none of the Americans in Russian hands had been spies, and in any event, the Russians welched on other parts of the deal and did not return to us the Americans whom the Germans missed. The whole affair was a mess, and my colleagues in New York who handled the case were thoroughly disgusted with the State Department over it. Later, reading over the 164-page summary report on Ovakimian, I was impressed by how much the FBI had been able to find out about the man - and was depressed by the fact that we had been forced to let him go.

Vassili Zubilin - alias Zarubin, alias Luchenko, alias Peter, alias Cooper, alias Edward Joseph Herbert - was another character from the shadows. All evidence pointed to the notion that he became the chief KGB resident in the United States after Ovakimian's departure. Zubilin and his wife, Elizabetha, were veteran KGB officers whose espionage activities dated back to the 1920s and had taken them all over the world. Zubilin was stocky and blond, with a broad-featured face and a manner that, according to those who had dealt with him, could be alternately pleasant and menacing. He operated from a position as third secretary of the Russian embassy in Washington.

As to his exploits, he seems to have been more of a "fixer" than Ovakimian, but perhaps this is because it was in this role that the FBI had caught more glimpses of him. We knew people who had worked with him at various times in Hollywood, San Francisco, New York and Washington. He was involved in everything from using a film company as a front to funnel money to clandestine activities, to attempted atomic espionage. Zubilin's personality seems to have been more outgoing and less cerebral than Ovakimian's - but both men survived the purges. Zubilin's name cropped up in a number of cases, and during my time in New York we charted his comings and goings and tailed him when the manpower was available. We tried to learn what he was doing; most of the time we didn't know. In later years, after he had left the United States, we heard that he had been made a general in the KGB, and that he had died an alcoholic.

Trying to counter the work of Ovakimian and Zubilin was a task full of frustration and repeated failures, with only occasional and partial successes-a pattern reflective of the difficulties the FBI experienced in fighting the KGB at the outset of the postwar period. In this intense but nearly invisible combat, counterintelligence was playing catch-up ball; the Soviets had built up an early lead and the FBI, new to the endeavor, was not as knowledgeable or as sophisticated as the enemy.

One evening in 1946 my friend Emory Gregg and I were bemoaning the fact that although we knew the top GRU man in New York (Pavel Mikhailov, the consul general), we had not been able to identify the leading KGB agents. Emory and I were aggressive and young, and had a lot of ideas for actions the Bureau ought to be taking against the KGB, but we didn't have much clout within the organization because we were just foot soldiers. This night we resolved to try something new.

The FBI thought that the U.S. headquarters for the KGB was in the Soviet consulate on East Sixty-first Street, a block off Central Park, and believed that the top KGB man, called the "resident," was in that consulate. Our knowledge of the Soviet espionage system suggested that while strings were ultimately pulled from Moscow, the New York resident had the power to develop targets of espionage, to enforce discipline within his own ranks and to insist on full reports from subordinates. Under the resident's direction, coded cables would be sent to Moscow (more bulky papers went in a section of the diplomatic pouch), and at his behest logs were maintained which noted the location and substance of all meetings between espionage agents and recruits. We knew a lot about the resident's job, but we didn't know his identity.

(4) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986)

Bentley had named more than eighty individuals as Soviet sources or agents, and said that a dozen different government agencies or government-associated groups had had their information stolen and delivered by her to the KGB. Because of the importance of her charges, Director Hoover had felt duty-bound to alert the White House, Cabinet officers and other top officials of her main accusations. But in the process of spreading Bentley's information throughout the upper echelons of the government, many of those whom Bentley had named learned of the accusations and had a chance to cease any questionable activities. And when hundreds of agents in the New York and Washington field offices mounted massive and intensive physical surveillance of all those who'd been named, this, too, had the effect of alerting the suspects and spurring them to cover their tracks.

In hindsight, these moves appear massive and clumsy, but Bentley's accusations were a pressing problem for counterintelligence in 1945-46, and the FBI had to do something about them quickly. The initial investigations did corroborate details of Bentley's stories-for instance, Harry Dexter White was observed to keep up extensive contacts with those in the Silvermaster network; the Silvermaster home was discovered to have a photo lab in the basement, as Bentley had said; people as diverse as Brothman, Perlo and Belfrage all worked in the positions and matched the descriptions Bentley had given of them; four people whom we'd suspected of being KGB agents were identified by Bentley from our photos as her former spymasters.

The problem was that, unlike Gouzenko, who brought out evidence in the form of telegrams and pages from Zabotin's diary, Bentley had nothing to backstop her stories - no documents, no microfilm, not even a gift of Russian origin which might have been traced. So very little in the way of prosecutions could be mounted, based on her recollections.

Privately, some of us were exasperated and thought we knew what could and should have been done with Bentley. I believe that very early the FBI could have forced things by moving in aggressively and interviewing everyone connected with her; in this way we might have gotten some of them to break, or to contradict one another's stories. We also could have obtained warrants and searched the Silvermaster home and the apartments of the Perlo group for evidence. No such actions were taken at the time. In addition, a number of leads were not pursued to their logical ends. For example, a cursory investigation of Abe Brothman turned up a business partner, Jules Korchein, whom the FBI thought for a time might be "Julius." But when agents discovered that Korchein didn't live in Knickerbocker Village and didn't precisely match Bentley's description of her night-time caller, the investigation was dropped. Had a list of Knickerbocker Village tenants been properly perused, the name of Julius Rosenberg would have turned up, a man with the name of Julius who did fit Bentley's description; more about that in a later chapter.Partially as a consequence of Bentley's charges, in the spring of 1946 there were many firings and enforced resignations in the State Department, the OSS, the Office of War Information and the Foreign Economic Administration. At the time, the public knew nothing of Bentley's role in all this, and in fact, Bentley was enjoined from saying anything in public for several years because she was a witness before grand juries. In 1947 one such grand jury was empaneled in New York specifically to investigate her accusations, and called such people as Abe Brothman and a business associate of his, Harry Gold - but indicted no one. It was not until the summer of 1948, after this grand jury had finished its work, that Elizabeth Bentley made her sensational debut before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and became known as the "Red Spy Queen."

After that, Bentley's accusations were ridiculed in public because only William Walter Remington, of those she named, was successfully prosecuted in this era. It's important to know, though, that later sworn testimony corroborated much of what she'd told the FBI. For example, both Whittaker Chambers and Nathaniel Weyl independently named members of what Bentley termed the Perlo network, and Chambers named others who Bentley had said were in the Silvermaster group. Other important corroboration came from the various testimonies of Louis Budenz, Bernard Redmont, Duncan Lee and the wife of William Walter Remington, Ann Moos Remington. Also, Katherine Perlo, ex-wife of Victor Perlo, wrote an anonymous letter to the FBI, which she later acknowledged, that backed up Bentley's naming of Perlo and his associates as being involved in espionage.

That spring of 1946, after the Bentley affair's initial phase, we in the New York office's Soviet Espionage squad felt frustrated: we were near and yet so far. Igor Gouzenko and Bentley had shown that Russians were operating all around us, but we were unable to counter their efforts.

(5) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986)

A tall, middle-aged, carefully dressed woman, no longer the striking beauty she had obviously been in her youth, Hede was still attractive. My early questions were so discreet that she leaned over the table to Finzel and me and said, "You don't need to be so delicate, Mr. Lamphere. I am very willing to tell you my story." Tell it she did, in many long interviews over the course of the winter of 1946-47. Of these interviews, Hede would later write that they had been, though polite, a "terrific ordeal," because it was hard to "pour your heart out to a stranger, to face yourself, your crumbled illusions, your misconceptions - it is like a psychoanalysis without reward."

Once more I heard about the cafes of Vienna, the home of the Bohemian life in the days at the end of World War I. Gerhart was a playwright. Hede was an actress, tall, slim, with reddish-blond braids, all of seventeen and on scholarship at the theater conservatory. She and her younger sister, Elli, came from a broken family. When Hede met Gerhart at a cafe it was as though she had "struck a whirlwind and was hopelessly and helplessly tangled and engulfed." Within weeks he had separated her from a weaker boyfriend, made her his mistress, and taken her to live with his family. The Eislers gave her warm family surroundings and intellectual stimulation. Hede never fully understood the Marxist doctrine, but implicitly trusted it and believed it to be humanitarian.

Hede and Gerhart moved to Berlin in 1920 and married-for convenience, he said, not because of bourgeois convention. In Berlin she starred in plays and he wrote editorials for Rote Fahne. Socially, they saw only fellow Communists. (I was reminded of Bentley's similar comments about the all-embracing environment that Communism provided - answers for all questions, jobs and lovers for true believers.)

By the time of the 1923 upheaval, Gerhart and Hede had grown apart, and Hede passed rather easily into the hands of wealthy Communist publisher Julian Gumperz, an intellectual Marxist who had been born in the United States. Her sister, Elli, moved in with them; Elli was fifteen, bright, beautiful, and "quite a self-centered little animal, wild and untamed." When Gerhart lost his job, Julian suggested he, too, take a room in the Gumperz house, and soon Gerhart and Elli were lovers. Hede took this as a compliment to her and a solution to the thorny problem of providing the great revolutionary with a suitable wife.

Hede and Julian made frequent trips abroad. In 1926, in New York, Hede met Helen Black and other Communists and worked as a "cottage mother" in an orphanage until her American citizenship papers came through, after which she and Julian moved back to Germany. At the university in Frankfurt-am-Main they met Paul Massing, an outdoorsman and agricultural economics student whom Julian thought a "rare combination of peasant boy and intellectual." Hede and Paul were both tall, Nordic-looking, passionate and romantic. They fell in love, and Julian let them go, helpless to stop their affair.

By this point in the interviews, Hede had become completely absorbed in telling me her story. I wanted her to feel comfortable enough to tell me details of her later espionage activities, but our relationship was often disturbing to me because it was based on a deep confession during which Hede's own perspective on her life changed dramatically. She was no longer young and attractive, but she was vivacious, and her coquettishness and wit were much in evidence during our sessions. It was easy to see why many men had desired her. She told me once that sex was no longer important to her; I doubted that.

In Berlin in the late 1920s the Massings and the Eislers saw one another frequently and led parallel lives. Gerhart and Paul played chess and Ping-Pong; then Gerhart was summoned to Moscow, and Paul went of his own accord to study agriculture. Languishing in Berlin, Hede had dinner with Richard Sorge, who later became one of the most successful Communist spies of the era. Sorge, formerly a Comintern man like Gerhart, had spirited his wife away from an older man, just as Paul had taken Hede from Julian. At dinner he convinced Hede that espionage was heroic and glamorous and that she, too, could do important things for the Party. He took her to meet "Ludwig," a man she discovered she already knew as a regular customer of the Gumperz bookstore, where she had worked for a time.

"Ludwig" was Ignace Poretsky, sometimes known as Ignace Reiss, a charming, erudite man who inspired near-fanatic loyalty on the part of Hede and many other agents. Together with his childhood friend Walter Krivitsky, "Ludwig" was a mainstay of Russian intelligence and had been so since the early 1920s. On his instructions Hede dropped her attendance at local Party meetings, provided details and evaluations of promising prospects, located "safe" apartments for agents and set up "mail drops" where messages could be exchanged - in short, she learned the rudiments of courier work. She did not use this knowledge right away, however, because she joined Paul in Moscow. When Gerhart came back to Moscow from China he was so arrogant that Hede could no longer speak with him. But then he had a heart attack, and she softened and visited him in the hospital.

In 1932 Hede and Paul both returned to Berlin and began to work for "Ludwig"; they told new recruits that espionage for the Soviets was really fighting against fascism. Paul organized in the universities, while Hede, with her American passport, ferried Jews and Communists out of Germany and into Czechoslovakia and Russia.

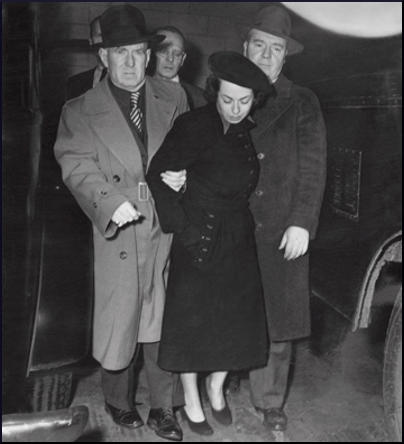

At the time Hitler came to power, Hede was on a courier mission from Moscow to Paris, carrying Comintern money in a false pregnancy outfit. In Paris she learned that the Nazis had thrown Paul into the concentration camp at Oranienburg; she hurried there with Communist underground help and watched for him from outside the barbed-wire enclosure. He yelled at her to go away and said he would join her when he could.