The schools that had cemeteries instead of playgrounds

- Published

Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission has released its findings into more than a century of abuse in Indian Residential Schools. Between the 1880s and 1990s 150,000 aboriginal children were sent to institutions where they were stripped of their language and culture. Many faced emotional, physical and sexual abuse.

I wriggled my way through an expectant crowd in a ballroom of a downtown Ottawa hotel. It was standing room only. Several hundred people, among them former residential school students, known as "survivors" - many of them now elderly - stood shoulder to shoulder with camera crews.

The event was going to be broadcast and streamed live across the country. Rarely had an aboriginal-led event attracted such national attention. Everyone was waiting eagerly for the long-awaited findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

While this moment was the culmination of a seven-year inquiry, many survivors had waited several decades to share their stories. Many had felt such shame at the abuse they had endured, that they never told another living soul, not their families, not their friends - until the commission arrived in their corner of Canada. The commission would allow them to at least begin their healing journeys.

The inquiry was more of an endless marathon, an odyssey. The three commissioners travelled tens of thousands of miles to hundreds of communities, even the most remote on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, to hear story after story of abuse. By all accounts, the work of the commissioners was relentless, physically demanding and emotionally gruelling. With the evidence now gathered, Canada was about to face a moment of reckoning.

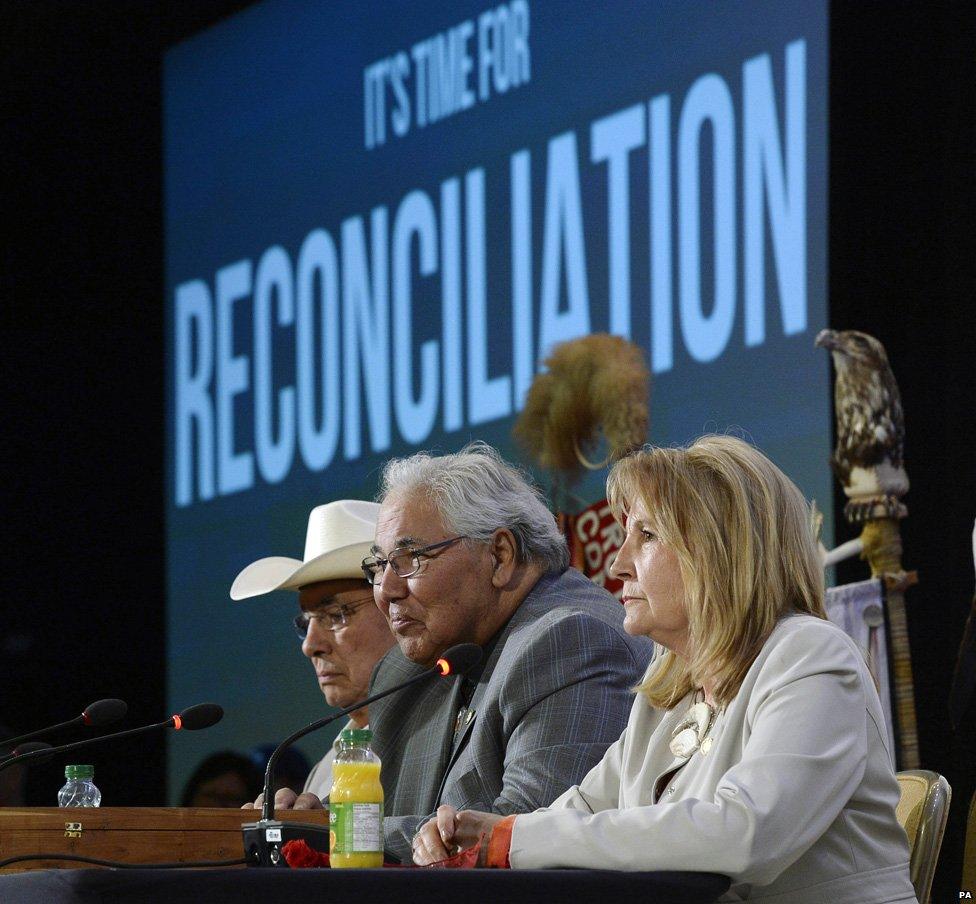

The room fell silent when Murray Sinclair, the chair of the Commission and Canada's leading aboriginal judge, approached the podium. Tall, commanding and august, his white hair seemed to have gone even whiter under the weight of the many sad stories he now carried with him. As he introduced himself, the room burst into a thunderous, deafening applause, accentuated by energetic drumming, wolf whistling and cheering. It was the kind of welcome normally reserved for a hero returning from a difficult mission.

Judge Sinclair, who described the residential school era as one of the "darkest, most troubling chapters" in Canadian history, began to read out his findings - more of a list of charges.

He said that seven generations of children were "stripped of the love of their families, their self-respect and … identity" over the course of a century.

In a deep, booming voice, he accused Canadian governments and churches of trying to "erase from the face of the earth, the culture and history of many great and proud peoples".

He said there had been "discrimination, deprivation and all manner of physical, sexual, emotional and mental abuse".

His words obviously triggered painful childhood memories. All around me, people began sniffling, shedding tears and even sobbing. Counsellors handed out tissues and glasses of water to the emotionally upset. It seemed that people hadn't just gathered to hear the report but to experience a collective emotional release.

Then, with two words, he issued his damning verdict: "Cultural genocide."

Again, the room erupted into massive applause. For them, it was a long awaited affirmation - but for many Canadians this would be bewildering news. Weren't they, after all, the nature-loving, nice guys? Judge Sinclair was showing them their dark side.

But he left it to a fellow commissioner to reveal the tragic news that 6,000 aboriginal children had died of malnutrition and disease at residential schools. Those were the ones they knew about. Many records, she said, had been destroyed. The school authorities clearly had little regard for the families - many were never informed about the loss of their sons and daughters. Often the boys and girls were buried on school grounds, which she described as having "cemeteries but not playgrounds".

Aboriginal children at a Canadian boarding school in the 1950s

"We can't un-know what we have learned," she said.

Judge Sinclair blamed the residential school system for the dysfunction, chaos and poverty in aboriginal communities today. They face high crime, addiction and unemployment rates and poorer-than-average prospects in health and education.

With the truth out, now came the reconciliation. Justice Sinclair laid down 94 recommendations, really pre-conditions to true reconciliation. Though one of them called for a formal apology from the Pope - many of the schools were Catholic-run - most urged Canada's political leaders to commit to closing the gap between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Canadians.

Thus far, the government has agreed to just one. However, in a sure sign that an election is looming, opposition parties agreed, if elected, to implement all the recommendations.

One of those key demands is that this shameful chapter of Canadian history be taught as a mandatory subject in all Canadian schools. No doubt one key date students will never forget will be the day Judge Sinclair made Canadians face up to their past.

More from BBC Magazine

BBC reporter Joanna Jolly went on the trail of the murdered and missing to find out why so many of Winnipeg's Aboriginal women and girls have been killed. Read full article

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.