Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

From Mary Todd Lincoln to Jane Pierce, they were swept up in the spiritualism movement of the 19th century—a belief that living souls can contact the dead.

The White House has hosted its share of prominent people: politicians, writers, musicians, scientists––and mediums.

Reflecting Americans’ belief in spirits unseen, some of the country’s first families held séances at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. They nursed their grief with the help of mediums, demonstrating that séances aren’t only about the deceased; they’re also about the living.

Spiritualism comes to the White House

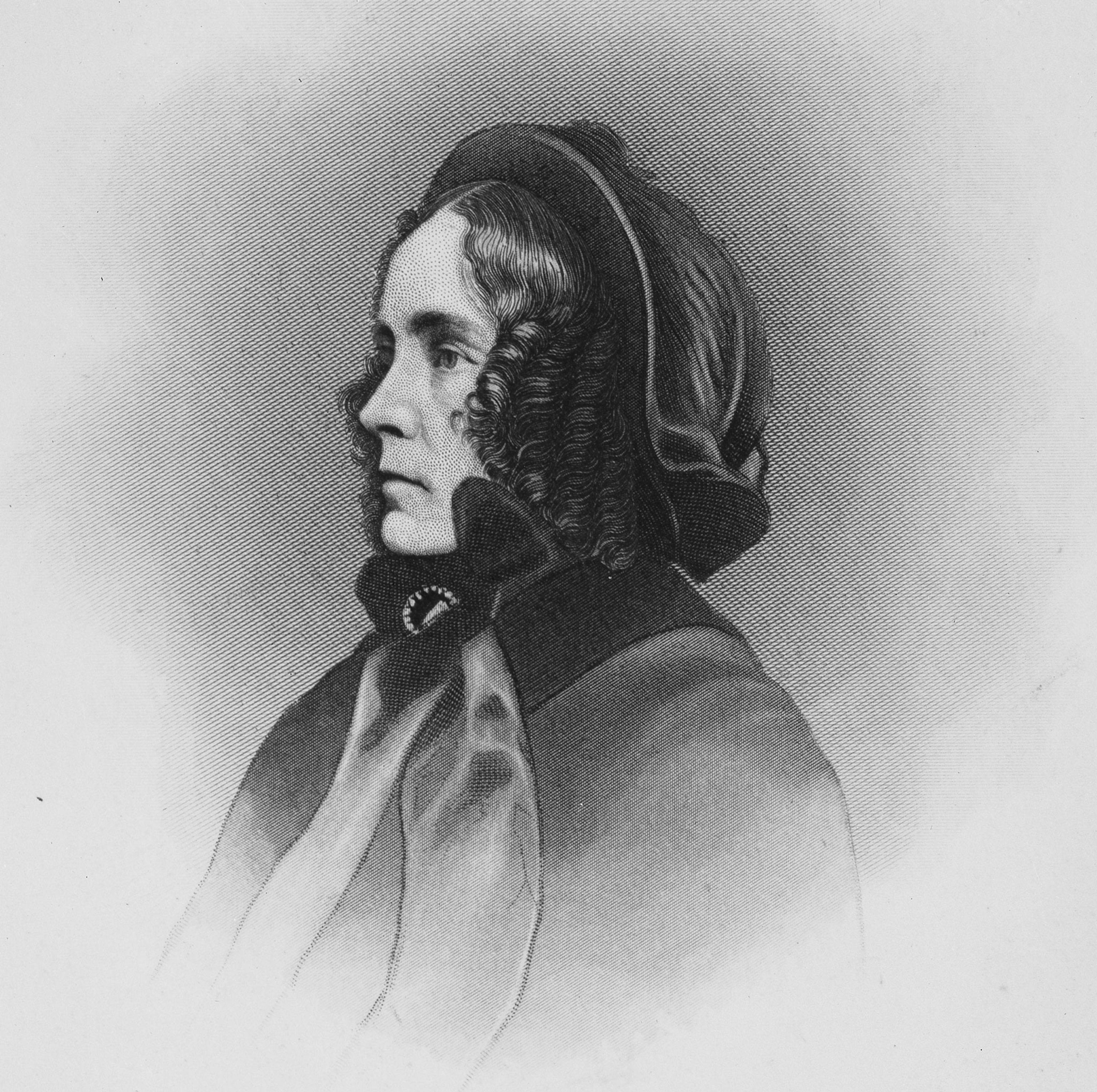

On January 6, 1853, newly elected president Franklin Pierce and his wife Jane experienced every parent’s worst nightmare. Their only surviving child, 11-year-old Bennie, died in a horrific train accident in Massachusetts.

Jane Pierce struggled to adapt to life without her child. She even wrote him letters as she secluded herself in her private quarters in the White House.

As Pierce fiercely mourned her son, a new religious movement took root across the country: Spiritualism, or the belief that the living could communicate with the dead. As historian Molly McGarry wrote in Ghosts of Futures Past, “a faith in Spiritualism and the experience that the dead continued to connect with the living” resonated in an America with an extensive mourning culture and “allowed some 19th-century Americans a new way of being in the world.”

Spiritualism’s popularity stemmed partly from 15-year-old Maggie and 11-year-old Katie Fox, sisters from Hydesville, New York. Though the pair lived relatively ordinary lives with their large family, they soon began making extraordinary claims. In 1848, they alleged that mysterious rappings in their family’s home came from a supernatural source: discarnate spirits. The sisters insisted they could communicate with them, interpreting the noises as a spectral form of Morse code.

The Fox sisters’ allegations electrified Americans eager to connect with deceased loved ones—individuals such as Jane Pierce. Fascinated by their narrative, she invited them to Washington.

(Discover how the world went wild for talking to spirits 100 years ago.)

No one knows what exactly occurred between Pierce and the Fox sisters. But the White House session may have mirrored the Fox sisters’ other séances, which commenced with guests sitting in a circle, holding one another’s hands, and reciting a prayer. Then, the rappings would begin, and the sisters would allegedly lift the veil on the spirit world.

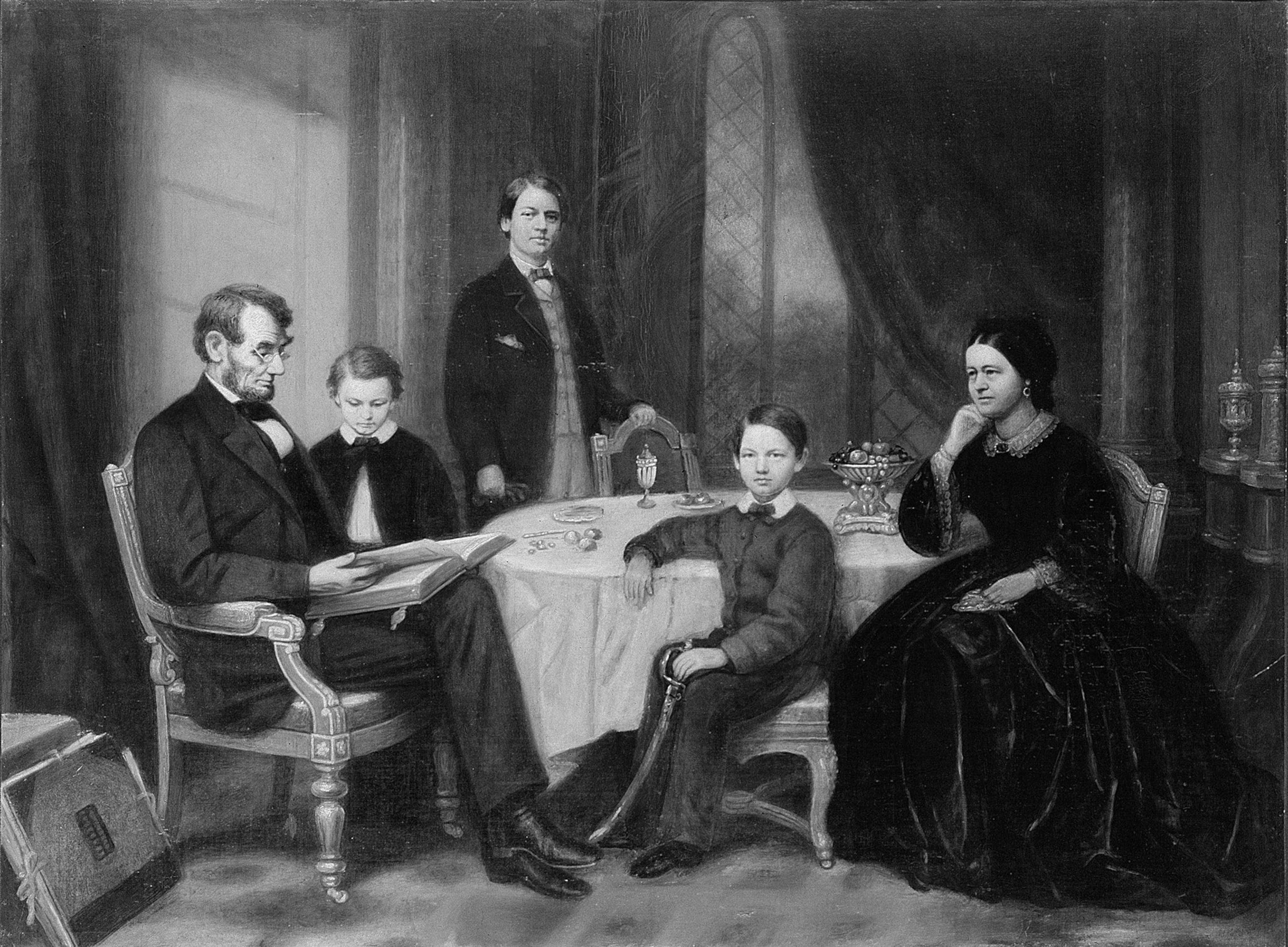

The Lincolns’ many tears

National and personal tragedy converged in the thick of the Civil War when Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln buried one of their children. On February 20, 1862, 11-year-old Willie Lincoln died in the White House after battling typhoid fever for weeks.

The boy’s death devastated both his parents, but Mary Todd Lincoln’s grief was especially debilitating. She stayed in bed for weeks and couldn’t bear to attend his funeral. But even when she rejoined society, Lincoln longed for a reunion with her deceased son.

So, she turned to mediums. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and Lincoln biographer David Herbert Donald used surviving documents to calculate that the first lady may have held eight séances in the White House.

One occurred in December 1862, when Lincoln hosted the medium Nettie Colburn for a séance in the Red Room.

Colburn later claimed that the president joined the séance––and that, in her trance-like state, she didn’t limit herself to communicating with Willie Lincoln. Instead, the spirits she channeled urged the president to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which they predicted would “be the crowning event of his administration and his life.”

Sessions with Colburn and other mediums stoked the first lady’s faith that souls survive death. She even saw Willie in her dreams. “Willie lives,” she told her half-sister Emilie Todd Helm. “He comes to me every night and stands at the foot of the bed with the same sweet, adorable smile he always has had.”

The last gasp of spiritualism

The White House was again in a state of mourning during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge in 1924. Coolidge’s 16-year-old son Calvin played a game of tennis––but he wasn’t wearing socks with his shoes. A blister formed on a toe and festered, and the infection turned septic. He died on July 7.

So, did the Coolidges employ a medium to contact their son? Harry Houdini, the famous illusionist, believed they had. He deplored spiritualism, séances, and mediums, all of which underwent a revival in the wake of World War I and the influenza pandemic. He was on a quest to expose mediums and psychics as the charlatans he believed them to be.

His greatest show in 1926 was when he testified in a Congressional hearing considering a ban on fortune-tellers. During the hearing, it was alleged that Jane Coates, a medium in Washington, D.C., had said, “I know for a fact that there have been spiritual séances held at the White House with President Coolidge and his family.”

(Harry Houdini’s unlikely last act? Taking on the occult.)

Coolidge’s friends vehemently denied the allegation, drawing a clear line between what was acceptable––and what wasn’t. Séances, it seemed, crossed the line of respectability in a changing America.

By World War II, spiritualism no longer attracted the acolytes it once had, and White House séances became a curious footnote in history.