SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

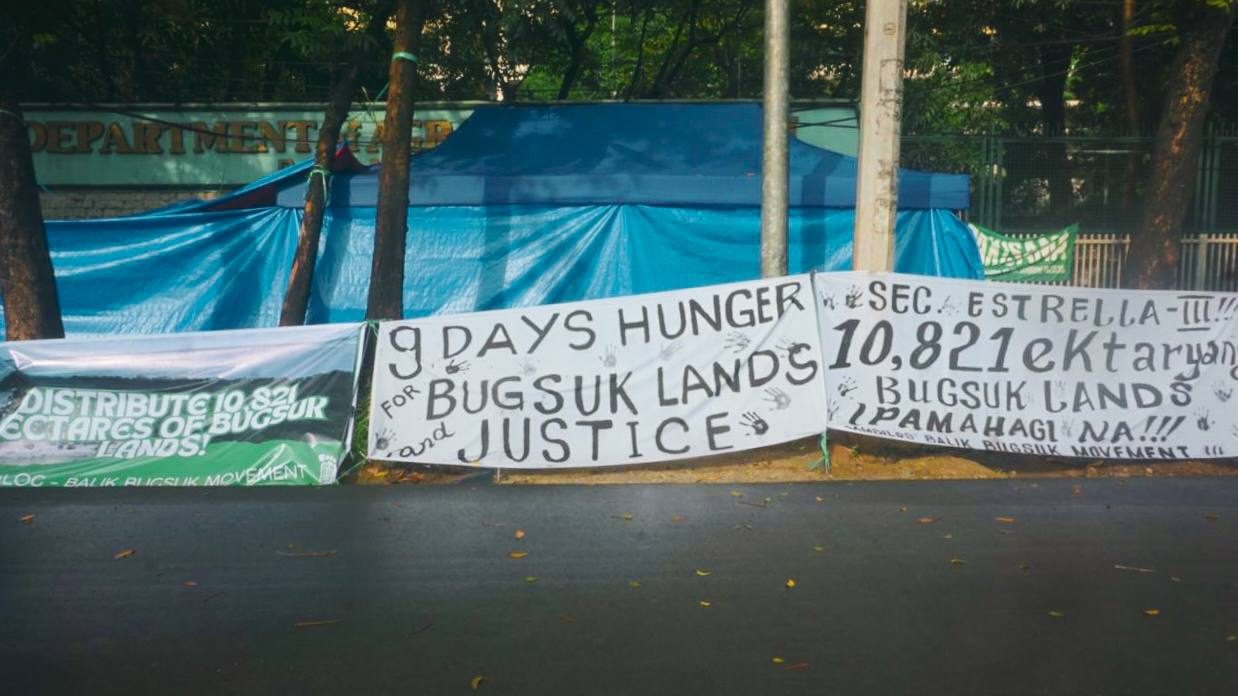

Rustene Leoncio, a member of the Molbog indigenous people from Southern Palawan, is on a hunger strike outside the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) in Quezon City.

It was the third day of the strike and his stomach has not yet adjusted to the lack of food. With certainty, he said things would get better in the coming days.

“Titiisin lang po basta mapansin ni Estrella,” Leoncio, 18, told Rappler in an interview on Wednesday, December 4. (We’ll endure it until Estrella notices us.)

Leoncio and the other Molbog and Palaw’an people arrived in Manila last September 13, in the hopes of raising awareness about the 50-year land struggle in Balabac, Palawan. They came from Mariahangin in Bugsuk Island, Balabac.

Their call is simple: that the government return to them the 10,821-hectare ancestral land that former dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos awarded to Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco Jr. in 1974.

The late Marcos gave this land in southern Palawan in exchange for 1,000 hectares of Cojuangco’s agricultural lands. Land swap was part of the government’s agrarian reform policy at that time.

In 2023, DAR Secretary Conrado Estrella issued an order exempting parcels of land in Bugsuk — included in the previous land exchange between the elder Marcos and Cojuangco — from the coverage of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program. This reverses the notice of coverage that DAR issued back in 2014.

The reasons cited for non-inclusion in agrarian reform were the properties not being suitable for agricultural production and the DAR having no power to overturn or reverse a contract that a president executed.

Now some Bugsuk residents part of the Sambilog-Bugsuk Movement that Leoncio and the others on hunger strike are a part of, want the whole 10,821-hectare land for distribution under agrarian reform.

Rappler asked Estrella for comment but has yet to receive a response. We will update this story once we get a reply.

An island resort in Bugsuk

A huge part of Bugsuk is now the subject of San Miguel Corporation’s (SMC) eco-tourism development.

In a statement published in full by some news sites on Monday, December 3, San Miguel Corporation (SMC) clarified their legal ownership of 7,000 hectares of titled properties in Bugsuk.

Documents related to the island resort of SMC subsidiary Bricktree Properties Incorporated said that the project area covers 5,567.54 hectares in total.

The company said the property was “acquired through the purchase of companies that have held the titles since their original issuance in 1974 as part of a government program involving the redistribution of agricultural lands to farmers under the Land Reform Program.”

SMC also said that they don’t own any property and is not involved in any projects in Mariahangin, where Leoncio and the other protesters came from.

Violent encounters in Mariahangin

Camping on the edge the Quezon City Circle, those on hunger strike endure the suffocating humidity from intermittent rain and the heat.

Before the strike outside DAR’s office, the group had been staying on Jesuit campus grounds for the past months. They miss home. But they don’t want to go back empty-handed.

“Paskong-pasko nandito. Gusto na namin umuwi sa mga pamilya namin,” Leoncio said. (It’s Christmas season already and we’re still here. We want to go back to our families.)

But home holds memories of violence for Leoncio. Last June, armed men entered Mariahangin in Bugsuk.

It was a day of festivities, Leoncio recalled, and they were at the basketball court holding a palaro (games). Then there were shouts. Armed men from San Miguel had come, Leoncio and the others heard.

He went in the direction of the commotion. Someone fired a warning shot. A man wearing a black bonnet and a black mask pointed a gun at Leoncio. The 18-year-old said he had to back out before the man decided to pull the trigger.

“Para akong nawala sa sarili,” he recalled. (I felt like I lost my mind.)

That was not the first time an armed group entered their island. Despite what residents said, SMC has denied being behind the armed men.

There was a recent encounter with armed men in November, caught on video by one resident. The tension did not tip over into a full-scale assault.

“Pulis kami rito,” a man in fatigues caught on the live feed was heard saying. “May karapatan kami rito, may karapatan kaming pumasok dito.” (We’re the police. We have the right here, we have the right to enter here.)

These episodes mark the long-running land conflict of Bugsuk people with private interests. Residents have long been wary of military activity.

The locals who were displaced when Cojuangco acquired properties in Bugsuk and Pandanan were “voluntarily relocated to other islands by the military,” wrote anthropologist Noah Theriault in 2014.

Theriault visited Bugsuk in 2007 and 2011, interviewing locals and studying the dynamics of the Sambilog movement and their resistance to Jewelmer Corporation’s pearl farm — owned by Danding’s brother, Manuel Cojuangco.

In a recent interview with Rappler, Theriault said he felt a “climate of intimidation” during his stay in the island, hearing sounds at nighttime that were uncannily similar to automatic gunfire.

“There was just a lot of tension and a feeling of surveillance,” Theriault said.

“You know, this idea if you went across the fence that you could get shot or if your boat went into the pearl farms’ area, you could get apprehended or worse.”

Homeland and identity

Despite a history of violence, the Southern Palawan indigenous people long for home.

Tarhata Pelayo, a Molbog elderly who is also fasting alongside the others, said she wanted to go back but they’ve yet to accomplish what they came to Manila for.

“Mas magandang umuwi nang nakangiti ka (It’s better to go home with a smile on your face),” said Pelayo. She traveled to Manila with her husband Eusebio Pelayo.

Aside from the reinstatement of agrarian reform coverage, their group wants the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples to process their application for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title.

SMC had said in its statement that they recognize the “importance of respecting the rights of legitimate indigenous communities” — language that may suggest an otherwise illegitimate indigenous community.

To this, Tarhata only said: “Patunayan ko sa kanila sinong magaling magsalita ng Molbog.” (I’ll prove to them who speak Molbog fluently.)

The issue of identity is not new. This was what Theriault wrote about after he stayed with the indigenous people of southern Palawan before.

“If they don’t represent themselves as pure indigenous people, particularly as vulnerable and needy, then they’re seen as having been corrupted somehow or having lost their authenticity,” he said.

Even advocates who want to support the cause were wary of this “loss of authenticity,” according to Theriault, because of the mix of migrant settlers and indigenous people.

“But I think what brought the people together in Sambilog was this shared experience of displacement, dispossession, political repression, intimidation,” he said.

The Molbog and Palaw’an people will end their hunger strike on December 10.

On December 13, they plan to go back to Palawan after three months away from home. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.