The headlines highlight the accepted conventional wisdom. “The Race to Regulate Artificial Intelligence: Why Europe Has an Edge Over America and China.” “Europe is Leading the Race to Regulate AI.” “The EU is leading the charge on AI regulation.”

Though the European Union is moving fast to pass its ambitious AI Act, the United States has also been advancing its own AI-related laws and broad governance efforts – in many ways at a much quicker pace than the EU. It’s critical to underscore this point for three main reasons.

- First, the US government’s AI legislative and regulatory efforts enhance its power to comment, critique, and push back on potentially counterproductive provisions in the AI Act and other artificial intelligence-related laws outside the US. A perception that the US government has done little undermines its authority — moral, technical, and otherwise — to opine effectively on other countries’ AI laws and lead in multilateral efforts such as the G7 Hiroshima Process.

- Second, the US approach, once clearly articulated, can be a model for countries to consider as an alternative or a complement to the EU’s AI Act. The AI Act – still in negotiation – has many virtues, but fundamentally, it is focused first on rules and second on how those rules will be defined, implemented, enforced, and evolved. By contrast, the US has emphasized building a regulatory infrastructure before moving to comprehensive regulation of AI products. Both models should be on the table.

- Third, the US government’s approach demonstrates a long-term and serious commitment to AI governance. Despite the challenging political environment in the US in recent years, both Democratic and Republican administrations and Democratic and Republican-led Congresses have championed AI governance efforts. The US government’s sustained focus on artificial intelligence shows allies and adversaries alike a clear commitment to act in the national interest.

The US was early to address the new technology. Its AI process started roughly 15 months before the European Commission convened its inaugural artificial intelligence expert group. In February 2016, the Obama administration released a report on artificial intelligence introducing the principle – later embraced by the EU’s AI Act – that the government should regulate based on risk assessments. The administration also published the first of three national artificial intelligence R&D strategic plans.

Two years later, the US was the first to legislate in the wake of China’s 2017 plan for world leadership in artificial intelligence. In 2018, the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (2019 NDAA) directed the US Department of Defense to coordinate the transition of AI into operational use, subject to appropriate ethical policies. The NDAA established the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI) to make artificial intelligence recommendations to the executive branch and Congress. The NSCAI’s final report provided a strong foundation for new US artificial intelligence laws that, among other goals, aimed to protect fundamental rights in government-deployed artificial intelligence.

Since then, the US government’s approach to AI legislation has continued to be wide and deep. In every fiscal year since 2019, the US has enacted at least one major piece of legislation on artificial intelligence. A review of 11 of these artificial intelligence laws reveals a strategy focused on national and economic security and built on five pillars:

- Build AI Governance Capacity by recruiting and training government personnel to support the development, acquisition, management, and regulation of AI and creating government organizations to coordinate across the federal government.

- Enhance Government Use of AI to, among other goals, improve financial and personnel management, expand the use of AI for climate science at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and ensure that AI acquired by the federal government protects fundamental rights.

- Provide AI Education by funding and supporting K-12 and postsecondary AI education and generating information, analysis, and research about AI in areas ranging from deepfakes to the impact of AI in the workforce.

- Fund AI Innovation by creating organizations such as the National AI Research Institutes and providing resources for artificial intelligence research ranging from AI and cybersecurity to ethical AI development.

- Influence the Private Sector to move toward safe, secure, and trustworthy artificial intelligence by, among other actions, leveraging the US government’s procurement power, developing standards and best practices, and providing operational guidance such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework.

The expertise developed from these legislative efforts led to the Biden Administration’s recently announced voluntary AI commitments. It helps guide the enforcement of existing federal laws in the artificial intelligence context and will form the foundation for President Biden’s expected executive order on artificial intelligence — itself the fourth artificial intelligence-related presidential executive order. Ultimately, the US approach serves as a solid foundation for enacting future legislation focused on the private sector AI actors as is currently being discussed in Congress.

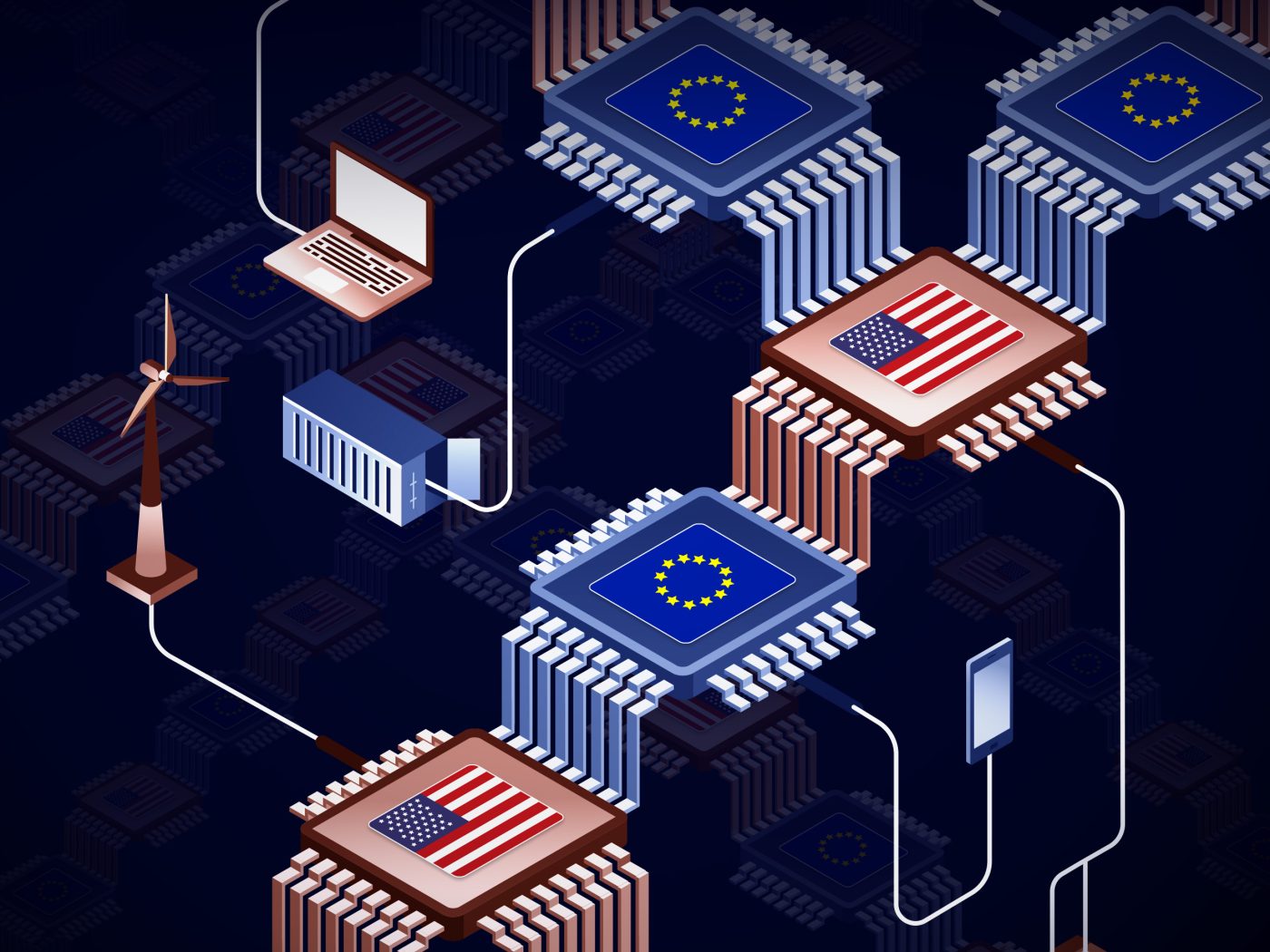

Although the US and the EU begin from different starting points and specific approaches to government regulation of artificial intelligence, both aim to ensure safe, secure, and trustworthy artificial intelligence bound to and driven by democratic principles. Both appear to agree on the need to align transatlantic artificial intelligence regulatory approaches – and both have done significant legwork to be ready for that challenge.

The so-called race between the US and the EU to regulate artificial intelligence can – and should – be less of a competition and more of a move toward a common goal informed by different approaches to meeting the same challenge.

Pablo Chavez is an Adjunct Senior Fellow with the Center for a New American Security’s Technology and National Security Program and a technology policy expert. He has held public policy leadership positions at Google, LinkedIn, and Microsoft and has served as a senior staffer in the US Senate.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.

CEPA Forum 2024 Tech Conference

Technology is defining the future of geopolitics.