Horrifically, the Hammond Circus Train Wreck, which killed eighty-six people, most of them performers, on June 22, 1918, was not the worst train disaster that year. It would be slightly surpassed in July by the Great Train Wreck of 1918 and in November by the Malbone Street Wreck, respectively the worst and second worst train disasters in United States history. Yet it was the circus train wreck which most direfully impacted the people of Cincinnati, Ohio.

When death came so dreadfully to the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus in 1918 the concern was the nation’s third largest circus company and the most important one in the Midwest. It employed some four hundred performers and roustabouts, whom it carried from city to city, along with scores of performing animals, in two separate trains of twenty-eight cars apiece. Without the advent of the marvelous mechanized horse, circuses could not have become the big businesses that they were in the second decade of the twentieth century. Five decades after the 1918 train disaster, torch singer Peggy Lee, in the second verse of her famous grammy award winning 1969 hit song, famously asked of a childhood visit to the circus, “Is That All There Is?” Yet typically for children and adults alike the circus coming to town marked a memorable and joyful occasion. In the early morning hours of June 22, however, it was not joy but terror which the Hagenbeck-Wallace circus performers experienced.

Having completed two shows in Michigan City, Indiana, the two circus trains were traveling overnight to the nearby city of Hammond, located between Gary and Chicago. The first train, which carried circus animals and workmen, made its way toward its destination entirely without untoward incident; but the second, on which rode the performers, was compelled to halt on account of an overheated hotbox. Around four in the morning it pulled off onto a side track, leaving five cars, including four sleeper cars made of wood, remaining on the main line.

As exhausted performers slumbered and repairs were made to the hotbox, a Michigan Central troop transport train composed of steel-frame Pullman cars recently emptied of soldiers enroute to deployment in Europe’s Great War suddenly cannoned into the prone circus cars, splintering their wooden frames like toothpicks and setting them aflame as kerosene oil spilled from the smashed glass lamps which had lighted the dark corridors. The Michigan Central engineer had missed all of the posted signals and warnings, having fallen asleep at the controls.

Many of the train’s passengers were thrown from their cars and survived, but others were trapped in the wreckage and incinerated. Among the dead were strongmen Arthur Dierckx and Max Nietzborn, their fabled strength fatally unavailing in this calamity, and aerialist Jennie Ward Todd of the famed Flying Wards, then pregnant with her partner-husband’s child, their first and their last. There were Cincinnatians in the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, largely roustabouts who had traveled on the fortunate first train. However, the sheer pathos of circus clown Joe Coyle, a native and winter resident of Cincinnati who lost his equestrian wife Estelle and their two young sons in the tragedy, received much sympathetic attention locally. Joe was thrown clear of the train but ran back to the car in an attempt to rescue his family. He heard his elder son Howard in the inferno, screaming “Daddy, Daddy, get me out, I’m burning!”—only to see flames engulf the boy. Afterward the clown tearfully told bystanders that he wished he had died with his family.

Among the victims were the all-too-often derided “sideshow freaks” who always rode the second train. “You hear a lot about freaks,” one circus person indignantly told the papers. “But let me tell you that in time of trouble the tattooed man or the fat lady or the snake charmer are more than likely to dig down for the cash to help out the unfortunate.” Meanwhile, freakish rumors ran rife among the frightened families of local farmers that lions and tigers had escaped from the burning train and were hungrily prowling the countryside in search of human prey. Fancifully it was even said that a noble troop of elephants had sacrificed itself to put out the great conflagration, dousing the flames with water they sprayed from their great hose-like trunks.

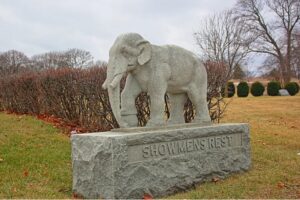

This guff about the animals was crackers, of course. What was true was that many of the disaster’s victims, their remains unidentifiable, became the inaugural dead interred at Showman’s Rest Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. There they were laid to rest in a mass grave of fifty-five caskets overlooked by five granite elephants, their inanimate trunks all down, as if in mourning.

*******

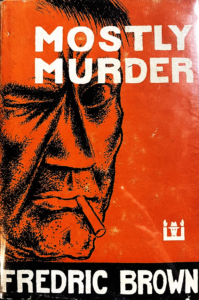

When the Hammond Circus Train Wreck took place, future crime and science fiction author Fredric Brown—one of the most imaginative writers ever to put fingers to typewriter keys, the creator of such classic crime novels as The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947), The Screaming Mimi (1949), Here Comes a Candle (1950), Night of the Jabberwock (1950), The Far Cry (1951), Madball (1953), His Name Was Death (1954), The Lenient Beast (1956) and Knock Three-One-Two (1959)—was a boy of eleven years, just two years older than Joe Coyle’s son Howard. The unnatural disaster at Hammond made the front page of the Sunday morning edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer on July 23, receiving placement above the war news and spilling over to take up all the space, aside from that which was devoted to all-important business advertisements, on the succeeding two pages. Two days later, the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus performed in Beloit, Wisconsin, the gaps in its decimated ranks generously filled by performers from rival circuses. The show must go on.

When the Hammond Circus Train Wreck took place, future crime and science fiction author Fredric Brown—one of the most imaginative writers ever to put fingers to typewriter keys, the creator of such classic crime novels as The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947), The Screaming Mimi (1949), Here Comes a Candle (1950), Night of the Jabberwock (1950), The Far Cry (1951), Madball (1953), His Name Was Death (1954), The Lenient Beast (1956) and Knock Three-One-Two (1959)—was a boy of eleven years, just two years older than Joe Coyle’s son Howard. The unnatural disaster at Hammond made the front page of the Sunday morning edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer on July 23, receiving placement above the war news and spilling over to take up all the space, aside from that which was devoted to all-important business advertisements, on the succeeding two pages. Two days later, the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus performed in Beloit, Wisconsin, the gaps in its decimated ranks generously filled by performers from rival circuses. The show must go on.

Before enrolling in school in Cincinnati, Howard Coyle, whom Joe had gifted with a clown suit when he turned four, had hit the circuit with his father, making a great impression as “the youngest clown in the circus business.” One imagines Fred Brown was one of the delighted spectators who had seen the Coyles perform their comic antics, then read in the newspaper about the shocking calamity which had befallen them, a tragedy which could not be casually laughed off even by the blithest perusers of the latest headlines. The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus was one of the troupes that made annual visits to Cincinnati, commencing their parade from the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton Railroad depot in Northside, the neighborhood where Fred Brown lived with his parents and maternal grandmother. Cincinnati was a circus clamoring city.

From his crime fiction, in which circus and carnival settings are abundant (see the novels The Dead Ringer and Madball, for example), it is clear that Fredric Brown had an intimate fan’s knowledge of the greatest shows on earth. One also finds in his work a powerful sense of the absurdly capricious cruelty of life: One day clowns may cavort under life’s big top, as it were, while on the very next they may perish in death’s deadly danse macabre. Clowns laugh, to be sure, but it is only to keep from crying. The show must go on.

Clown Joe Coyle

Clown Joe Coyle

Fred’s knowledge of this showbiz credo was not merely vicarious. His father on more than one occasion found himself dragged into court as a party to business fraud, and before Fred was even twenty years old, he had become an orphan. The rest of his life was a parade of wild and wooly and sometimes decidedly unwonderful happenings, and he died a lingering, painful death from emphysema at the age of sixty-five. “The joke is on us,” crime writer Bill Pronzini has written of Fredric Brown’s bemused and frequently mordant view of the world and its weird people, “and it is a joke that all too frequently turns nasty.” There is laughter, but it is “laughter with plenty of teeth in it, and with tragedy lurking darkly at its perimeters.”

*****

The only child of Karl Lewis and Emma Amelia Brown (nee Graham), Fredric William Brown was born in Cincinnati, Ohio two days before Halloween in 1906, the year in America of the San Francisco earthquake and the Atlanta race riot, two outstanding testaments to the malevolence both of nature and of nature’s petty human playthings. Karl Brown was born in 1871 in the small town of Oxford, Ohio, located about forty miles northwest of Cincinnati, which over the half century that extended from the 1870s, when Karl grew up there, to the 1920s, when Fred as a teenager and young man came up from Cincinnati to visit his uncle Linn Brown, barely increased in size, maintaining a population of around 2000 people. A pastoral college town, it was home to the bowered academic groves of Miami University and Oxford Female Institute.

Karl’s father was Waldo Franklin Brown, a nationally prominent progressive agriculturist who from his rural fastness in Oxford edited the farm pages of the Cincinnati Enquirer and published articles and pamphlets under the name “Johnny Plowboy.” Born in 1832, around the time, as legend would have it, that the “Rail-Splitter” Abraham Lincoln was romancing winsome Ann Rutledge in little New Salem, Illinois, Waldo Brown married twice, in 1859 and 1871, and sired six children, a quartet of daughters and a pair of sons, between 1861 and 1874. Waldo passed away at the age of seventy-four in 1907, eight months after his grandson Fredric’s birth. His second wife, Laura Alma Cross, by whom he had his two sons, Karl Lewis and Linn Waldo, was a schoolteacher who graduated from Oxford Female Institute, a Presbyterian women’s college whose first president, John Witherspoon Scott, was the father-in-law of post-Civil War American president Benjamin Harrison, another native Ohioan. His daughter, First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison, was the Institute’s most famous graduate. Laura Brown died at the home of her second son Linn in Oxford in 1929 at the age of eighty-eight.

In the early 1890s Karl Brown forsook the Edenic little world of Oxford and moved to hustling and bustling Cincinnati, then a burgeoning metropolis of some 300,000 people (about the same size as it is today). There in 1894 he married Emma Graham, daughter of a railroad mail clerk, when he was twenty-two and she was twenty. After a dozen years of marriage—quite a long delay—Emma bore the couple’s only child, whom they named “Fredric” without the second “e” and the “k,” like actor Fredric March.

Karl Brown was descended from New England Presbyterian stock going back to Massachusetts and Vermont, while Emma hailed from a Scots-Irish Presbyterian line which went back to Pennsylvania. Emma’s grandfather Reverend Jacob Graham had administered the gospel at Graham’s Chapel in Lodi, a tiny habitation in rural Ohio. As far as I know, these Grahams had no relation to the renowned late evangelical revivalist minister Billy Graham of North Carolina, who likewise was raised a Presbyterian, although the two Graham lines doubtlessly intersect somewhere in Scotland if one goes back far enough.

Fred Brown later claimed that his father was an ardent atheist, as he himself was, and that his mother was an agnostic. Neither their Graham nor Brown ancestors would have been pleased to broadcast Fred’s unheavenly revelation about his parents. Aside from Jacob Graham, Waldo Brown had a brother who was a Presbyterian minister and himself was a presbyterian church elder and Sunday-school superintendent. As “Johnny Plowboy” he supported abstention from liquor in no uncertain terms, writing in one of his columns in 1905:

Johnny would, if it is proper, like to give you a brief history of the men he has known in his town who have wrecked fortune, health and everything worth living in the indulgence of [drink]. One drowned himself in his own cistern; another was murdered in a saloon; several died of delirium tremens; one of a “whiskey liver.” Many have…brought their families to penury. Will it pay for the temporary gratification of a depraved appetite to run all these risks?

Whatever the true answer to Waldo’s surely rhetorically-meant question, his progeny Karl and Fred proved to be risk runners.

*******

No “simple, honest farmer” like Johnny Plowboy, Waldo Brown’s materialistic son Karl evinced far greater interest in collecting the top dollar in the here-and-now than in clambering to glory over mythical pearly gates. In Cincinnati Karl became a myrmidon—salesman, corresponding secretary, accountant—in the shady business enterprises of a substitute father figure, William P. Harrison, a pioneering if not overly scrupulous entrepreneur of direct mail marketing. Beginning around 1890 Harrison—a son of an Ohio farmer and possible distant relation of native Ohio American presidents William Henry Harrison and Benjamin Harrison—created a highly successful conglomeration of mail-order companies headquartered in Columbus and later, after Columbus had gotten too hot for him, Cincinnati. By 1910, Harrison stood at the pinnacle of his success, a millionaire residing at a mansion in the stately Cincy neighborhood of Rose Hill.

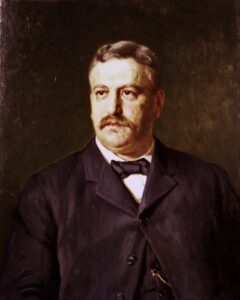

Gilded Age Cincinnati proved a fertile breeding ground for men with the ability and cynical willingness to manipulate circumstances to their own personal advantage. Between the late 1880s, when Karl Brown was about to arrive, into the 1910s, when his son Fred was a little boy, the Queen City was ruled by a king, or rather a political boss: George B. Cox, a native Englishman who had risen from humble circumstances to reign as the Ohio River burg’s greatest string puller. From his base at the notorious saloon nicknamed “Dead Man’s Corner,” where he also ran a lucrative bookmaking operation, Cox took over the local Republican party and created his own mighty machine, acquiring dozens of bars and burlesque theaters and becoming the most powerful man in the city, a cigar-smoking puppet master manipulating pliable pols and judges.

By the first decade of the new century Cox had become one of the most notorious bosses in the country. The muckraking Everybody’s Magazine denounced Cincinnati as “the worst boss-ridden city in the United States.” Finally in 1908 reformist forces, who depicted machine Republicans as corrupt promoters of gambling and prostitution, managed to elect and reelect an anti-corruption county prosecutor, Henry Thomas Hunt. When he ran for mayor of Cincinnati in 1911, Hunt was supported by none other than American president William Howard Taft, another native Ohio Republican whose own brother Charles Phelps Taft, editor of the Cincinnati Times-Star, was one of Boss Cox’s most prominent puffers. Hunt defeated the Cox-backed incumbent, finally humbling the Boss of Cincinnati, who thereupon announced his retirement from politics. The ex-boss died five years later at the age of sixty-two after a suffering a debilitating stroke.

In Fred Brown’s parable-like vignette “Town Wanted” (1940, later reprinted in Ellery Queen’s anthology Rogue’s Gallery) the narrator Jimmy, an on-the-make hood with ambitious plans for himself, might well be a Cagneyesque, Depression Era version of George B. Cox. Brimming with confidence in society’s corruptibility, Jimmy cockily explains to the reader: “I know how I’ll start, when I’ve picked my town. I’ll take a tavern for a front. Then I’ll find which politicians are on the auction block. I’ll see that the others go out. Money can swing that. Then I bring in torpedoes and start to work…. [I’ll form] protective societies—where the merchants pay you to let them alone. That’s the big dough racket, if you’re not squeamish.” Fred could be describing the career of George B. Cox, (the B stood for Barnsdale), among any number of other American Gilded Age city bosses.

In this fetid environment direct mail tycoon William P. Harrison thrived like a foul-smelling orchid luring flies for pollination.In this fetid environment direct mail tycoon William P. Harrison thrived like a foul-smelling orchid luring flies for pollination. Like Gaul, the Harrison commercial empire was divided into three parts: World Manufacturing Company, makers of bath cabinets; Gray & Company, an electroplating works; and R. Armstrong Manufacturing Company, purveyors of vacuum cleaners. From a six-story building on Elm Street, the millionaire commanded his commercial army of 120 men and a score of lady stenographers. The glass-fronted door bore the names of his companies. At his desk, modestly marked off from the main office by wire mesh, the mail-order mastermind sat like a spider in an intricate web—or the villain in an Edgar Wallace thriller— wearing sinister smoked glasses and dictating letters into a phonograph in a whispery voice.

The latest concern in William P. Harrison’s business triumvirate, the R. Armstrong Manufacturing Co., was named after the Great Man’s so-called “confidential secretary,” English native Rose Armstrong. Although Harrison was a married man, the husband of the former Emma Shrontz, one suspects that his relationship with his delicate, pale English Rose, a “mere wisp of a girl” as the Cincinnati Post described her, may have been of rather a more intimate nature than simply taking dictation from the boss. Rose, who had been employed by Harrison since the turn-of-the-century when she nineteen, may well have been one of that breed of business secretaries, as a newspaperman character cynically observes in Fredric Brown’s crime novel The Screaming Mimi (1949), who had to take good care to watch her periods as well as her commas. At her untimely death in 1912, Rose, then thirty-one, loyally left all of her money, stocks and bonds to her sixty-three-year-old former boss, whom she also had made executor of her estate.

Back in the Naughty Nineties, William P. Harrison, taking advantage of the splendid commercial possibilities offered by the blessed advent of the two-cent postage stamp, mailed letters, circulars and catalogues all over the unsuspecting country, heralding the many miraculous benefits of his reasonably priced emporium of consumer wonders. His bathroom cabinetry promised regular folk “all the delights of a Turkish bath at home,” while his electroplating apparatus enabled purchasers, like medieval alchemists, to turn their tarnished metalware “shiny as silver.” Best of all were the legendary Armstrong vacuum cleaners, which belying their fearsomely cumbrous appearance, even a child or “weakly woman” could operate easily, producing delightfully dustless, healthy homes.

Back in the Naughty Nineties, William P. Harrison, taking advantage of the splendid commercial possibilities offered by the blessed advent of the two-cent postage stamp, mailed letters, circulars and catalogues all over the unsuspecting country, heralding the many miraculous benefits of his reasonably priced emporium of consumer wonders. His bathroom cabinetry promised regular folk “all the delights of a Turkish bath at home,” while his electroplating apparatus enabled purchasers, like medieval alchemists, to turn their tarnished metalware “shiny as silver.” Best of all were the legendary Armstrong vacuum cleaners, which belying their fearsomely cumbrous appearance, even a child or “weakly woman” could operate easily, producing delightfully dustless, healthy homes.

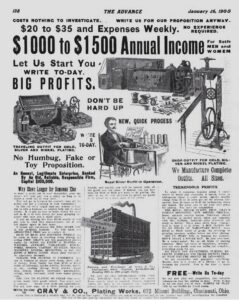

“Think of it!” exhorted an Armstrong vacuum cleaner newspaper ad which appeared in 1911. “This great blessing, heretofore only possible for the rich, now within the reach of all—rich or poor—village, city or country.” All for only $8.50 (about $280 today). And it worked just every bit as well as, if not better than, vastly more expensive models! Similarly, a 1906 magazine ad from Gray & Co assured readers that they could make ample livelihoods from electroplating, once they had purchased all of the equipment. “Why Slave Longer for Someone Else,” exhorted the advertisement in large bold font. “$1000 to $1500 Annual Income for Both Men and Women. Let Us Start You. Write To-Day. Big Profits. DON’T BE HARD UP.”

William P. Harrison advertised nationally in newspapers for sales agents as well, making extravagant promises of the riches which were sure to fall down like electroplated raindrops upon lucky takers of this fantastic chance:

FOLLOW THE DOLLAR. $50 to $250 per week; money’s yours; dazzling money-making proposition; entirely new; not worn out; field untouched; money pours in; women weep for joy; free samples to agents; fascinating reports…. John Logan gave up $12 job driving teams; now makes $50 weekly; agent’s profit 100%; risk a penny to bring a flood of success; send postal for agency.

Alas, all was not what it seemed to seem in this promised commercial paradise. The day after New Year’s in 1908, Karl Brown, then a salesman for Gray & Co., was arrested by two Cincinnati policemen on a warrant sworn out by Benjamin Arboleda, a Mexican national and buyer for several Latin American business firms who claimed that Brown had obtained a draft from him for $419.75 ($14,000 today) under false pretenses. According to Arboleda, he had called upon the offices of Gray & Co. after seeing one of their advertisements, in order—no fool he—personally to witness a demonstration of their vaunted electroplating apparatus. He was given the runaround for several days and never did get to see said apparatus in operation, yet he was cajoled into signing a paper which, Brown told him, was a visitor’s register. Displeasing word came later to Arboleda that five cases of machinery from Gray & Co. had arrived at the port of Mobile, Alabama, for shipment to Latin America. Karl Brown insisted that the Mexican knew what he had signed and was just trying to weasel out of their contract. William P. Harrison paid Karl’s bail, liberating his salesman from prison, and presumably the case was settled.

****

The Arboleda Affair was not Karl Brown’s last adventure in court. The medicinal whiff of hygienic reform had begun to pervade the miasmic fug that once had covered Cincinnati. Nearly three years later in December 1910, while county attorney Henry Thomas Hunt pursued a perjury case in state court against Boss Cox himself, federal marshals arrested Karl’s own boss on charges of mail fraud. Now William P. Harrison’s bookkeeper, Karl was compelled to testify in the case, which drew national attention. The United States Post Office, the Enquirer reported, fruitlessly had “been endeavoring to keep Harrison to the straight and narrow path of honest business methods for 15 years past.” All over America customers inundated post offices with letters lamenting that Harrison’s companies had bamboozled them into throwing away their hard-earned cash on utter junk. With the ascension to power of President William Howard Taft and his zealously antifraud Postmaster General Frank Harris Hitchcock (another native Ohioan), Harrison had been given one “last chance to do business within legitimate limits.” Only briefly did he straighten his path before letting it run crooked once again.

During 1910 alone, R. Armstrong Manufacturing Co. through the mails had sold over 37,000 vacuum cleaners—a gross of more than ten million in modern dollars—but staggeringly received in return ten letters of complaint for every commendation. “The cleaner consists merely of a pair of bellows which have to be operated by hand,” reported the Enquirer, adding that “it takes a strong person to try to clean even one room.” Agents as well as customers complained of having been callously deceived by the designing mastermind of the company. It seemed that William P. Harrison’s ruling business motto might well have been those words attributed, however inaccurately, to circus showman P. T. Barnum: There’s a fool born every minute.

In 1911 newspapers revealed that Michael P. Harrison’s confidential secretary Rose Armstrong was actually nothing less than the Vice President and Secretary of the R. Armstrong Manufacturing Co. This allowed the Post to inject a bit of sex appeal into the case, running a large photograph of the soberly dressed lady executive, who looked more like a nervous schoolgirl, under the incredulous caption, “Girl ‘Head of Firm’ to Testify in Harrison Trial.” Rose “was very close to Harrison,” as the Enquirer suggestively put it, and she appeared “to know regarding his affairs much more than she was willing to admit.” The pack of eager Cincy news hounds also divulged that back in 1895 Harrison had been prosecuted, along with his then-partner, on charges of mail fraud in Columbus, Ohio. The wily businessman had avoided a prison term by promptly turning state’s evidence against his elder, erstwhile partner in white-collar crime. What else is a man to do? The show must go on.

When faced with federal prosecution in 1910, Harrison, like comedian Martin Short’s gaslighting attorney Nathan Thurm in an Eighties SNL sketch, was defiant, telling the press: “I’m not worried…. there’s nothing to worry about. It’s strange…that the government permitted me to do business for so long without interfering with me, if I ever did anything wrong.” After the Cincinnati case went to trial in February, however, a veritable battery of outraged customers testified that Armstrong’s 100% money-back guarantee was a palpable fiction, the company having frequently attempted falsely to claim that it had never received returned cleaners.

The most memorable testimony came from John B. Gunn, a fifty-five-year-old man who lived with his fifty-two-year-old wife in the town of Collierville, Tennessee, not far from Memphis, and owned a farm in Mississippi. In the packed Cincinnati courtroom, which Gunn had determinedly travelled five hundred miles from Collierville to reach, the farmer told how he had tried the Armstrong machine himself when his wife complained of the extreme exhaustion she had suffered after having futilely attempted to use it. Explaining that he was a hard-working man who baled cotton in a mechanical gin and put hands to a heavy horse plow, Farmer Gunn, no “weakly woman” he, avowed that if ever given a choice between furrowing a field or cleaning a room in his house with an Armstrong vacuum cleaner, “I would rather handle a plow.”

An embarrassment for the defense occurred when the District Attorney asked Karl Brown whether he had an Armstrong vacuum at his home in Conway, Kentucky, across the Ohio river from Cincinnati, then, upon learning that Karl did, elicited from him the fact that his wife had never used it. Karl redeemed himself during a demonstration in which “sand was rubbed into a long strip of carpet placed on the courtroom floor” and “forced through to the carpet paper underneath.” Manning an Armstrong machine “to prove that the cleaner would take dirt from under the carpet, as claimed in advertisements,” Karl seemed successfully to suck up sand.

Karl was again put on the spot, however, when during his testimony he contended that the reason R. Armstrong & Co. had not promptly refunded dissatisfied customers the previous year was that “business was bad and money was not available.” This gave the DA the opportunity to demand to know whether Brown was aware that in Texas Harrison owned an immense tract of land and controlling stock in a telephone company. Karl claimed that this was news to him.

When the testimony concluded in March, the jury after six hours of deliberation found Harrison guilty on all seven counts of mail fraud with which he had been charged. According to the Post, the jurors took time themselves to run Harrison’s vacuum cleaner through a “thorough test” by applying the machine to the carpet in their own deliberation room. Sadly for Harrison, it did not, in their estimation, get the carpet clean. The convicted millionaire faced a faced a fine of up to $7000 and a term of up to thirty-five years in jail, but the judge sentenced him to a relatively lenient thousand dollar fine and a three-year term of incarceration at the federal prison at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

On “hearing” the verdict—Harrison was said actually to have had to lip read it because in the last few months he had become almost deaf—the defendant at first smiled over the $1000 fine but then at the prison sentence “shook like a leaf” and sank back, utterly defeated, into his chair. His ever-faithful confidential secretary Rose burst audibly into bitter tears. (Mrs. Harrison seems not to have been present in the courtroom.) The Post complained that in its blind zeal to prosecute the direct mail tycoon, the government would cost Cincinnati $10,000 dollars in annual stamp sales (about a third of a million dollars today), not to mention deny newspapers and magazines $100,000 ($3.3 million today) in annual advertising revenue. This contention notwithstanding, the federal district attorney pugnaciously vowed to pursue a “national crusade” against mail order houses using “glowing literature” to exaggerate “the quality of their wares.” “Those firms will have to stop misleading the public,” the D. A. avowed.

“VACCUUM CLEANER MAN IS CONVICTED IN FEDERAL COURT,” read the headlines. A heartbroken Rose Armstrong died from the rapid onset of Bright’s Disease in July 1912. In December, however, the laissez faire U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Harrison’s sentence, opining that the “not uncommon exaggeration” of the prisoner’s business advertising did not constitute fraud, the federal statute not having been meant, in the court’s estimation, to cover “such puffing of goods as is found in the vacuum cleaner circulars.” Caveat emptor! The show must go on.

Unfortunately for the disgraced ex-millionaire, this surprise reprieve came too late in the day. Worn out with it all—Rose’s death, his imprisonment, his failing investments, the disastrous negative publicity about his mendacious “puffing”—Harrison passed away age sixty-five in May 1913, less than six months after his release from prison, at Laurents Point, Vermilion Parish, Louisiana, where he had gone in an attempt to recover his failing health. Both his daughter and his son, a clerk in one of his father’s companies, had predeceased him, leaving his widow to die alone in 1940 at her small apartment on Erie Avenue, the glories of her husband’s bath cabinetry, electroplating machines and vacuum cleaners long since having rusted and come to dust.

There was another human casualty in the Harrison matter: Rose’s close friend May Severson, a schoolteacher who had resided with Rose at a cozy bow-windowed apartment on Court Street. Whatever had been the exact nature of Rose’s relationship with her boss, May Severson had obviously become very attached indeed to her friend. Gather ye rosebuds, May.

On the first-year anniversary of Rose’s death, a couple of months after Harrison’s demise, May, whom Rose had left her all of her “clothing, jewelry, household goods and other personal effects,” placed this moving notice in the Enquirer:

In Loving Memory

of my dear friend, Rose Armstrong, who passed into life eternal July 23, 1912.

May light perpetual shine upon her.

From Her Devoted Friend, May Severson.

May Severson, loyalist of spectators of Rose Armstrong’s rich pageant of life, died single six years later at age forty-seven during the great flu pandemic. She had taught diligently for a quarter of a century at the Rothenberg School in Cincinnati. Her fourth-grade pupils attended her funeral at Christ Church Chapel, the school having been closed for the day in her honor.

Boss Cox

Boss Cox

*******

While William P. Harrison’s companies may have may have crumbled in the aftershocks of his conviction, taking some human casualties with them, crafty Karl Brown like a nimble cat landed safely amidst the wreckage on all fours. Employed in 1920 as the manager of a Cincinnati machine tool company, he had moved back to the Queen City from his abode across the river in Conway, Kentucky (where many of Cincy’s vice merchants went after the reformists came to power) to an attractive 2300 square foot Italianate brick house at 1530 Chase Street in Northside, where he resided with wife Emma, son Fred and mother-in-law Sara Graham. Within six years, however, all of the members of the Brown household aside from Fred would lie moldering in their graves, leaving Fred alone. Like the Hammond Circus Train Wreck, it was a cruelly rapid succession of deaths such as might sour anyone on the callous way of the world, which kills us seemingly for sport.

In 1965, when Fredric Brown was nearly sixty years old and slowly dying from the emphysema that would finally make an end of him at the age of sixty-five in 1972, the author published an embellished recollection of an episode from his life entitled “It’s Only Everything.” Inspired by a recent visit from a zealous and “quite handsome and very young” male Jehovah’s Witness missionary, Fred Brown pensively wrote about how he came decisively to cast out religion from his own life for good. The earnest missionary lad “kept on talking and I, hung over and in my pajamas, kept on listening,” he remembered, “because in seeing him I saw myself, in a way in which I could have gone, if there were a God and if upon a certain occasion, he had deigned to alter a minuscule part of the cosmos and perform a miracle for me.”

Fred Brown seems to have written very little about his past, but he does discuss a bitter episode from it in “It’s Only Everything”—though what he chooses to discuss there is not always accurate and has misled people who have previously written about his life. Fred claims that although his father was an “admitted atheist” and his mother a “mild agnostic,” they decided, presumably sometime in 1915 when Fred was “eight or nine years old,” to expose their son to religion, so that he could make his own judgment about its truth or falsity. They all joined a church, as Fred tells it, “Presbyterian as it happened, probably because it was the nearest one,” and Fred was enrolled in Sunday school. “A few years later he “became an actual member of the church.” This holy house was North Presbyterian Church, an impressive brick Victorian Gothic structure originally constructed in 1855. It was only a four minutes’ walk from the Browns.

It seems improbable in the extreme that Fred would not have realized that, his parents both having come from prominent, devoutly Presbyterian families, they naturally sent him to a church of that faith, but this is the lesser oddity in the account. Fred writes that he attended the local Presbyterian Church between the ages of nine and fourteen, from 1915 to 1920, which was “the most mixed-up period of my life” on account of all the glories of religion, yet another con game in the author’s view, being heaped into his head. In the latter year he learned that his mother was terminally ill with cancer, and that her death was imminent. Upon being told this horrible news he “ran out of the house crying,” praying fervently to God “that if he would cure my mother, would pass the miracle of making her well again, I would devote the rest of my life to him, would become a missionary to Darkest Africa or wherever he might send me.” Despite his desperate pleading his mother soon expired from the dreadful wasting disease, leading him to realize “that Christianity except for a part of its code of ethics was a mess of crap.”

“It was such a relief to be able to become, or to admit that I was and really had been all along, an atheist,” reflects Fred. “To know that henceforth I could be governed by my mind unwarped.” Those days came insistently back to his mind, he says, forty years later, while he was listening to that earnest, handsome young Jehovah’s Witness drone on about the bountiful goodness of God. Yet Brown’s essay was published in April 1965. Unless it was actually written five years earlier in 1960, the dates are off: His mother could not have died in 1920.

It in fact was not Emma Brown who died in 1920 but rather her mother, Fred’s grandmother Sarah Graham. Emma actually lived on for another three years, passing away at the age of fifty on December 2, 1923. Fred’s formal loss of faith likewise would have taken place, then, in 1923, when Fred was seventeen and a junior in high school, not a fourteen-year-old in his freshman year. If we adhere to the adult Fred’s recollected five-year framework, he actually would have begun attending church in 1918, the year of the Hammond Circus Train Wreck, when he was eleven or twelve. Why did Fred change the year of his mother’s death? Was it to make the story more poignant by reducing his age? Was Fred embarrassed to admit to crying over his mother at the age of seventeen? Did he deliberately misremember his adolescent past?

*******

We know what Fred looked like at this time, due to the availability of his 1925 senior class photo, taken at Hughes High School when he was eighteen, a little over a year after news of his mother’s imminent death had sent him into the Cincy streets unconsolably weeping. Blonde and delicately featured and smiling a Mona Lisa smile, young Fred—who at the time was nicknamed, perhaps inevitably, “Brownie”—appears a veritable angel of a choir boy, something which he may well have been at church. At Hughes he was a member of the Annual Staff, the Commercial Club, the Salesmanship Club and the Sages; and he was commended as a “musician of note” (he played the flute) and one of the high school’s littérateurs, having already published stories and poems in the school magazine. His motto was “a poet is a musician of words.”

The annual added of “Brownie”: “It seems that his ability is inversely proportional to his size, for he is one of the smallest members of our class.” Fifteen years later his 1940 draft card listed his height as only five foot five and a half and his weight as but 120 pounds. From his annual photograph, young Fred looks like the most innocent and vulnerable high school male senior imaginable, utterly in contrast with the drab, wizened forty-year-old man, bespectacled and balding, who looks out dourly at the camera in the photograph on the back of the jacket of his first novel, The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947). Fred suffered from asthma and allergies and a predilection toward bottle-tipping, all of which gradually worsened over the course of his life and prematurely aged him. One would not have known the man from the boy.

Sex and seediness, blood and booze-soaked bums are such recurring features of Fred’s adult fiction that his innocent, boyish appearance in 1925 (he would marry only four years later) comes as a surprise. It is something like seeing a then-and-now comparison of Truman Capote, circa 1980, from fey, youthful elf to woozy, drug-addicted troll. Yet Fred may have had more knowledge of sex than his high school photo suggests.

Although Brown authorities have neglected to mention this detail, the author in “It’s Only Everything” divulges, in connection with his having spent the night with his church minister as his dying mother neared her earthly end, that the man was a repressed homosexual with an intense attraction to pretty male youths like Fred in his flock. “He loved to have boys sleep with him; he made no passes but found every excuse for physical contact and chaste caresses,” Fred recalled. “What a poor, tortured guy he must have been. And what a good man.”

This “poor, tortured guy” would have been Reverend William Arthur Motter, a short, stocky, single man of thirty-eight, the son of a Swiss-descended shoemaker from Iowa and a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1920, when he was an assistant minister, Motter had lodged at the local YMCA chapter, but by 1923 he resided at a large two-story brick Victorian home just a five minutes’ stroll up Langland Street from the Browns’ place, or an even shorter run when one is, say, distraught and crying over the impending demise of one’s mother. Five years later Motter left North Church to become minister at the presbyterian church at the town of Kenmore, New York, in which capacity he served for twenty-four years. He never married, but was said in his obituary in 1967 to have “traveled extensively” and been “active in youth work”—words which carry a more ominous ring after reading Fred’s revelations.

Earlier in 1923 there had been a stir at North Church when three members of the resurgent Ku Klux Klan, which had begun organizing in Cincinnati three years earlier and now claimed nearly twenty thousand adherents in the metropolitan area, entered the Presbyterian house of worship while Reverend Motter was conducting services. Motter carried on as usual and the Klansmen made no disruption, quietly departing after leaving money in the collection plate. Recently Klan members had been invited to attend Cincinnati’s primitivist Richmond Street Christian Church, where its youthful, blond, blue-eyed, twenty-nine-year-old minister, Orval William Baylor, had openly and enthusiastically embraced the Klan (he was a member himself), proclaiming it not “anti” anything but simply “pro-American.” Emboldened Ku Kluxers now desired to establish other sanctified beachheads within the city. At North Church they had received no encouragement. Reverend Motter, remember, in Fred’s estimation was a “good man,” in spite of his regrettable predilection.

Fred’s prevailing tone toward Reverend Motter is not one of hostility, condemnatory of a wicked groomer of children; rather, it is sympathetic, sadly understanding of human foibles, the concluding words And what a good man seemingly sincere, not sarcastic. The nearly sixty-year-old version of Fred had wearied, worldly wisdom, but what knowledge had the sensitive and vulnerable eighteen-year-old boy possessed? Were his teenage years the most “mixed-up period” of his life partly because his parents had him attend a church where his own minister was smitten with the attractive blond boy in his congregation? Were these years of anxiety and confusion for Fred, as the birds pecked and the bees stung like the denizens of famed beekeeper L. L. Langsroth’s hives (see below), rendering the lad painfully uncertain of his own sexual identity?

In his 1956 crime novel The Lenient Beast, Tucson cop Frank Ramos—apropos of nothing, really, but surely recalling the author’s own recollected youthful experience—observes of hotel clerk Paul Geissler: “He was a good-looking young man with blonde, wavy hair, the kind you’d trust with your sister but not with your kid brother.” Three years earlier Brown published Madball, a paperback original crime novel, wherein he takes the reader on a deep dive into the sordid world of traveling carnivals. One of the major characters in the novel is Sammy (we never learn his last name, which he doesn’t know): a “simpleminded,” homeless young man, perhaps barely out of his teens, with a “nice smile” whom Jesse Rau, operator of the milk bottle game, has taken in to perform odd jobs for him and not incidentally gratify his sexual lust. His first night at the carnival, where “he’d walked the midway dazzled by the bright colors and the happy music and tortured by the smell of frying hamburgers…. Jesse had yelled ‘Hey, kid!’ at him and from that moment everything had been all right. Jesse had asked him if he wanted to set up milk bottles and earn a little money…. And then after a while Jesse had…bought him a meal…and…a second meal….” There was just one catch, but even that was bearable if it meant having a home and food to eat: “That night Jesse had taken him to the little green tent that he’d learned was a sleeping top and had said they’d sleep together, and something had happened that night that had hurt him, hurt him bad, but Jesse had fed him and so anything Jesse wanted to do to him was all right, anything.”

Later Sammy himself starts finally to have stirrings about sex, “wondering why women were different from men.” He asks Jesse why “men pay money to see women pose that way [nearly naked], to which Jesse indifferently replies: “Damn if I know either, kid.” Carnival mentalist Doc Magus, who refers to Sammy as “that halfwit kid…Jesse’s punk,” wonders to Wiggins, the carnival owner, whether Sammy is “going to start giving Jesse trouble now.” (Presumably he means the younger man might forcibly object to being anally penetrated by the elder one.) Wiggins chidingly comments: “I hope he does. None of my business, but that’s something I don’t like. Why doesn’t Rau get himself a broad?” To which Magus nonchalantly replies: “Some guys are that way, that’s all. In Sammy’s case I’d say it’s a break for him Jesse’s like that; who’d watch out for him if Jesse didn’t take care of him? He’d have to go to a nuthouse or starve to death.”

Do we feel certain that nothing ever might happened between young Fred and the consolatory, caressing, kindly Reverend Motter?

*******

The same year in which he published The Lenient Beast, Fred announced, perhaps facetiously, to the Tucson Press Club that “I’ve never written a true word in my life.” Certainly factual error crept into Jack Seabrook’s Fred-reliant 1993 critical biography of the author, Martians and Misplaced Clues: The Life and Work of Fredric Brown, which is far more focused on the author’s work than his life. Drawing mostly on Fred’s own accounts, Seabrook misdates Emma Brown’s death to the spring of 1920, then compounds the error by asserting that Karl Brown died the next year, leaving Fred an orphan at age fourteen; and that Fred “lived with the family of a friend in Cincinnati until he completed high school in June 1922.” According to Seabrook, Fred survived on proceeds from his father’s life insurance policy, which were “doled out” by an apparent uncle in Oxford, Ohio. This of course would be Karl’s brother Linn, who had faithfully remained at home while Karl made for the big time in Cincinnati.

Seabrook then asserts that after graduation, Fred worked for a couple of years as a clerk in a “machine tool jobbing firm.” While the next three years are blank, Seabrook tells us that in 1927 Fred spent a semester at Hanover College, a private Presbyterian school eighty miles away in Hanover, Indiana, followed in the fall with a semester at the University of Cincinnati, after which “money ran out and he had no inclination to continue” life as a college boy. Meanwhile at some point he had begun, lonelyhearts like, romantically corresponding with Helen Ruth Brown, “a woman who may have been a distant cousin.” Supposedly Brown had only ever seen a snapshot of Helen when he proposed marriage to her by mail. The pair finally laid eyes upon each other for the first time when they wed in 1929.

Unfortunately, this is a vague and often implausible and factually inaccurate chronology. As already explained, Emma Brown died in 1923, not 1920. Karl Brown’s admittedly premature death took place not in 1921, but rather on October 17, 1926, almost three years after Emma’s passing and just twelve days before Karl’s twentieth birthday. Fred, then, was not a fourteen-year-old boy commencing high school, but a nineteen-year-old young man, nearly twenty, who had already been out of high school for a year. He graduated from high school not in 1922 at the age of fifteen, but rather in 1925 at the age of eighteen.

Since we know that Karl managed a machine tool company (and was not, as Seabrook stated, a newspaperman), does it not seem likely the “machine tool jobbing firm” which Seabrook says Fred worked for between 1922 and 1924 was actually his father’s firm? And that he actually worked there in 1925 and 1926, between his high school graduation and his father’s death? And that he started college in 1927, after his father died and he had left the employ of the machine tool company and his Uncle Linn was doling out to him insurance money?

A big part of the confusion here stems from a literal reading of Fred’s 1958 mainstream novel The Office, which like Cornell Woolrich’s mainstream novel Hotel Room, coincidentally published the same year, draws on biographical elements from the author’s own life, though these elements frequently are deliberately distorted. Fred set the events of The Office at the premises of a Cincinnati machine tool jobbing company, generally basing it, one assumes, on the company which his father served as office manager. He somewhat awkwardly introduces himself as a character in the novel by name, Fred Brown, just graduated from high school, yet for some reason he backdates his college graduation from 1925 to 1922 and has Fred Brown of the novel declare that his father died in 1921 and his mother five years earlier in 1916. He also vaguely references an uncle in Oxford who doled out money from his father’s insurance policy so he could finish high school while boarding with the family of a friend in Northside. Out of this hodgepodge of half-fact and half-fancy Seabrook got the notion that Fred graduated from high school in 1922 and that his father died in 1921, while he erroneously relies on the essay “It’s Only Everything” to conclude that Fred’s mother died in 1920. Obviously, this was far from everything: what was needed were facts, not just Fred’s recorded and distorted recollections.

In The Office Book-Fred explains that he completed “a commercial course in high school”—“bookkeeping, typing, salesmanship, stuff like that”—and that his grade point average after four years was ninety-one. He hopes “to get a little actual office experience and then…start looking for a job as a bookkeeper or clerk, or at least a typist.” This sounds on point with the real Fred’s life, though the chronology of course is off by a few years. As already stated, Fred likely originally was hired as an office boy by his father after he graduated from Hughes High School. Book-Fred mentions having worked summers for Wurlitzer and Potter’s Shoes, both of which were actual Cincinnati companies with whom he might well really have been employed. Book-Fred, an eager devourer of fiction by H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, Sax Rohmer and Edgar Rice Burroughs and E. W. Hornung, admits that what he really wants to be in life is a writer, which certainly rings true. “I would read like an alcoholic drinks,” Book-Fred recalls of his office boy days. Sadly, the older Fred—the real one—would also drink like a bibliophile reads.

There is another character in the novel, Marty Raines, who is worth noting, for he bears resemblance to the real-life Fred as well. A twenty-one-year-old bookkeeper, Marty is, like Fred then was, short and slight (five foot seven and 130 pounds) and wavily blond. In another detail that rings true to Fred’s life, we are told that Marty “stopped growing at seventeen; he knew that for certain, as he had badly wanted another inch or two of height and had kept careful measure of himself between the ages of seventeen and twenty, when…he had given up.” Poor Marty is rather repressed and neurotic about sex, having been raised by his pious mother “not only to believe strongly in God, in Whom many believe without harm, but to believe even more strongly in the Sacredness of Womanhood.” Fred claimed his mother was mildly agnostic, even though she came from a devoutly religious background, but, in any event, this aspect of Marty’s personality possibly reflects Fred’s own youthful tussles with his unruly moral conscience.

In The Office Fred does not seem to draw much, if at all, on Karl Brown’s role in William P. Harrison’s fantastical mail order kingdom. Fred, after all, was just a very young boy when his father worked for Harrison, who died when Fred was six years old. Had Karl ever told Fred anything about his past with his controversial employer, however? Quite possibly so. This sardonic passage, which concerns the machine tool company for which Book-Fred works as an office boy, certainly seems suggestive of Harrison’s triad of flapdoodle direct mail businesses:

Conger & Way…had several names besides their own. In the special language of business, especially in the early part of the century, they operated under the styles of the Screw Machine Products Co., the Midwest Lathe Supply Co., and the Perfection Abrasives Co. In black-outlined gilt lettering—worn but legible—these names appeared on the outer door of the office under the that of Conger & Way…. the Perfection Abrasives Co. owned or contained no abrasives unless one counted as such the nail file in the top drawer of Mary Horton’s desk. The Midwest Lathe Supply Co. owned only the three-quarter-inch No. 2 center with Morse taper shank that served as a paperweight for Mr. Conger; and the nearest thing to a screw machine possessed by the Screw Machine Products Co. was a pencil sharpener, and it produced no products except sawdust and powdered graphite, both in quantities too small to have commercial value.

Conger & Co. owner Edward B. Conger (the B stands for Benjamin) is fifty-nine, around the age of William P. Harrison at the time of his downfall in 1910-13. He is married to a wife for whom he has no passion, but his sex drive in general is exhausted. In the original draft of the novel, which was deemed too scabrous to print by Fred’s publisher, Conger unambiguously is, like Reverend Motter, an unwitting homosexual whom Book-Fred denigrates as “an ill and aging fairy who had never known that he was one and never would know.” It is not his wife nor his son and daughter but rather his late male partner, Harry Way, whom Conger ardently loves.

Certainly around the time of his real-life troubles William P. Harrison was himself, like the fictional Edward B. Conger, ill and aging. Yet one imagines that Harrison was possessed of ardor neither for his longtime wife nor the former partner he had betrayed, it apparently being his confidential secretary Rose Armstrong who lit his love candle. However, in the novel Conger poignantly goes to his death while “in the middle of a dream in which he and Harry Way were young again and both unmarried, starting out their business in an office—an office at the top of a flight of golden stairs. They were climbing those stairs, Harry—handsome, beloved Harry—in the lead and young Eddie Conger following a few steps behind.” Jack Seabrook deems this passage a dream of “success and youth rather than homosexual longing.” Personally, I would firmly pencil in the circle beside “all of the above” and trust the scanner to grade it.

Appropriately the office clock which Book-Fred tells us was “the most important thing in [the office]” is named Hammond. This name was lettered on the clock “almost as large as the numerals.” When Fred named the godlike device which “regulated our lives” in the office could he conceivably have had in mind the Hammond Circus Train Wreck, which had halted the show for good for so many people back in 1918? Mere coincidence, you say? Perhaps so, but the Hammond Clock Company of Chicago was not founded until 1928, four years after Fred’s fictional office was closed. A Hammond clock could not have been there when Fred was.

*******

Fredric Brown must have maintained closer connections with his father’s family than has been appreciated. Almost all of his paternal relations—his father’s mother Laura Brown, widow of Waldo, three of his father’s four half-sisters and, most important, his father’s brother Linn—resided in Oxford in the Twenties, where they were honored as one of the town’s “oldest pioneer families.” Jack Seabrook did not know the name of Fred’s mysterious Oxford benefactor uncle, but the fact that his name was Linn is hugely suggestive, given that Fred named his second son, who was born in 1932, Linn. The younger Linn must have been named in honor of Fred’s uncle. Significantly, neither of his sons was named after his father Karl. The elder boy, born in 1930, was named James Ross Brown, with the middle name derived from his wife’s father, Thane Ross Brown. Did Fred harbor conflicted feelings about Karl? Fred explores conflicted father-son relationships in some of his novels, like The Fabulous Clipjoint and Here Comes a Candle.

It was Linn—not Karl, as has been claimed—who was a newspaperman, albeit in a modest fashion. For most of his adult life Linn was an Oxford grocer, residing on Church Street about a half-mile from downtown at a modest two-story frame house with his wife, Bessie, and his unmarried schoolteacher daughter, Dorothy, who was Fred’s single cousin on his father’s side of the family. (There were three on his mother’s side living in Indianapolis whom Fred may never have met.) However, in the 1920s Linn retired from the grocery business and became Oxford correspondent for the Journal-News in Hamilton, Ohio, a city of over forty thousand people located fifteen miles northwest of Oxford, as well as the Times-Star and Daily News of the larger burgs of, respectively, Dayon and Cincinnati. Linn also served as Oxford’s public health officer. When in 1937 he died from a sudden heart attack at age 62, leaving behind his wife and daughter, Linn received a two-column obituary in the Hamilton Journal-News, which declared that “his accomplishments will be long cherished.” Linn was buried, along with his father and mother, half-sisters and the prodigal Karl (though not Emma) in the old family plot at Oxford.

When one comprehends Fred’s connection to Oxford and his Uncle Linn, it is certainly suggestive that his series detectives Ed and Am Hunter, who appear in seven of Fred’s twenty-two crime novels, are an uncle and nephew team. Moreover, in all likelihood Oxford provided the background for one of the author’s most highly regarded crime novels, Night of the Jabberwock, and Uncle Linn much of the inspiration for the novel’s protagonist.

Set in the fictional small town of Carmel City, Jabberwock concerns one wild night in the life of Doc Stoeger, editor for twenty-three years of the town paper, the Clarion. The novel opens on a Thursday night with Doc and his linotypist, Pete, putting the weekly edition to bed for Pete to run off on Friday morning. There are significant distractions for Doc along the way.

Set in the fictional small town of Carmel City, Jabberwock concerns one wild night in the life of Doc Stoeger, editor for twenty-three years of the town paper, the Clarion. The novel opens on a Thursday night with Doc and his linotypist, Pete, putting the weekly edition to bed for Pete to run off on Friday morning. There are significant distractions for Doc along the way.

A somewhat melancholy figure who like the author himself loves the nonsense writing of mathematician Lewis Carroll and dreams of someday reporting a big scoop in his newspaper (after twenty-three years seemingly an extremely unlikely event), Doc in the opening pages of the novel reflects: “For once, for one Thursday, the Carmel City Clarion was ready for the press early. Of course there wasn’t any real news in it, but then there never was.” He tells Pete: “if only something would happen just once on a Thursday evening, I’d love it. Just once in my long career, I’d like to have one hot story to break to a panting public.” To which Peter prosaically replies, “Hell, Doc, nobody looks for hot news in a country weekly” and Doc responds wistfully: “That’s why I’d like to fool them just once.” Surely Fred is describing a life much like that of his Uncle Linn, correspondent for a pacific little college town which back in 1930 had a population that numbered all of 2588 souls. This number actually represented a population “explosion” of twenty-one percent during the Twenties, being an increase from 2146 in 1920.

As Oxford’s health officer Uncle Linn himself may well have been dubbed “Doc” locally, like Doc Stoeger in Jabberwock–though one hopes that Uncle Linn was not an oblivious alcoholic like the protagonist of the novel, who over the course of the evening and early morning hours detailed in the novel by my count downs more than thirty drinks of hard liquor (more inferentially). As Bill Pronzini has observed of Doc Stoeger: “Doc consumes enough liquor…to land the average person in the hospital with alcohol poisoning.” One suspects that the author may have derived that particular quality more from himself.

*****

Karl and Linn Brown had four older half-sisters: Alice, Winona, Florence and Berta. One assumes that Fred would have known all of his Brown aunts, who passed away between 1929 and 1944. Alice Brown, who never married, taught at Holbrook College, a teacher’s school located thirty miles east of Oxford at the town of Lebanon, and she took over the family farm after Waldo’s death. Alice also served on the editorial staff of the Rural New Yorker, an important rural farm paper which reached thousands of subscribers throughout the northeastern United States. The second sister, Winona Brown, was a physician who moved to New England and married a farmer there. The couple had no children.

Fred’s Aunt Florence Brown—who, like Alice, never married and died in 1929, like Fred at the age of sixty-five–was a stenographer who later served as custodian of Langstroth Cottage at Western College for Women in Oxford, a national historical landmark where the so-called “father of American beekeeping,” L. L. Langstroth, a friend of Waldo Brown, had lived for three decades during the last third of the nineteenth century. Florence’s lifeless body was discovered one day bolt upright in a chair in her bedroom at the cottage. There is a good macabre story here for the Fredric Brown reader, though presumably Florence Brown had not been stung to death by bees or affrighted by ghastly supernatural manifestations.

Another strange tale concerns the last of Fred’s paternal aunts, Berta Brown, who married Alvin Gaston, an Oxford farmer and antique dealer. Berta made news back in 1922 for being among the first women in the county to serve on a jury. She was joined by no fewer than eight other ladies (along with three men), which struck the local press of the day as a decidedly amusing novelty; but presumably the nine ladies good and true managed to pay attention to the legal details and not lapse into womanly chatter about the latest labor-saving home appliances–vacuum cleaners say–and tasty recipes for potato salad.

In 1935, six months after Berta died in 1934 at the age of sixty-eight, her husband Alvin, said to be deeply despondent over his loss, committed suicide by slashing his wrists and throat. Or so the county coroner concluded. (You do not read mysteries without becoming suspicious of such a succession of deaths.) This really is something out of a ghoulish Fredric Brown novel, with some notable parallels to The Screaming Mimi, such as, obviously, the razor murders in the novel as well as the gift shop which pivotally sells a customer the “screaming Mimi” statuette.

Alvin Gaston was said to have owned “one of the largest and finest collections of antiques in the state,” much of which was auctioned at his death, the Gastons having had no children. Alvin’s hoard of more than a thousand Native American relics, including arrowheads and axes (see Fredric Brown’s Here Comes a Candle for more on the subject of axes), went to his nephew Victor James Smith, an archaeologist at Sul Ross Normal College at Alpine, Texas.

Did Fred ever see his uncle-in-law’s remarkable antiquarian collection? A Brown story which Professor Smith conceivably might have helped inspire is one of Fred’s finest, “The Spherical Ghoul,” which Bill Pronzini praised for having “one of the cleverest (if outrageous) central gimmicks you’re likely to come across anywhere.”

Rather reminiscent of Alvin Gaston himself is the character of John Glosterman, the murder victim in Fred’s 1944 puzzler “The Djinn Murder,” the first of the nine stories which he placed in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Glosterman collects “objects connected with primitive superstitions: old idols, spirit gongs, juju masks, voodoo drums—all that sort of thing.” Certainly the strange deaths of Fred’s Aunt Berta and Uncle Alvin might have helped inspire the author’s mordantly macabre frame of mind. In life one never knows when or in just what bizarre guise death might come deviously to call.

*******

In short, Fredric Brown on his father’s side had a fascinating, if rather nonprocreative, family with whom the orphaned young man likely spent considerable time in the 1920s. Yet up until now nothing, to my knowledge, ever has been written about this. It appears even Fred’s own sons knew little about it. They did not even know much about their own parents’ marriage.

Fred and his first wife, Helen Ruth Brown, wed in Cincinnati on April 13th, 1929. The couple tied a youthful knot like Fred’s parents had. Fred was twenty-two and working as a stenographer and Helen twenty-one and staying transiently at Cincinnati’s Gibson House Hotel. While Helen, like Fred, had completed a year of college, it seems doubtful she ever held salaried employment. In his introduction to Nightmare in Darkness, a volume of Fredric Brown short fiction published in 1987, the author’s son Linn Brown writes of this union, stating: “[Fred] married her, Helen, hardly knowing her. The courtship was conducted totally by mail. When he wrote her suggesting marriage, he’d seen only a snapshot. I wish I knew more about that.”

As do I. For it seems inconceivable to me that this very brief account, upon which Jack Seabrook relied, can possibly be accurate. Helen and Fred were not what I would call distantly related, as Seabrook allows that they might have been. Rather they were, Poeish-like, second cousins. Helen’s father, Thane Ross Brown of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was Fred’s father Karl’s rather more prestigiously employed first cousin. On their marriage license the couple attested that they had never been previously married and that they were no nearer kin than second cousins, which just barely fit the bill. The state of Ohio prohibited first cousin marriages.

Would second cousins Fred Brown of Cincinnati and Helen Brown of Milwaukee really have been near strangers to each other before they wed? And would they have met each other through a correspondence service, just happening coincidentally to discover that they were second cousins? That truly would have been a coincidence out of a book, perhaps one by Cornell Woolrich or Fred himself, say Waltz into Darkness or The Far Cry.

After they married, the young couple moved to Milwaukee to live with Helen’s family and Fred’s kin at their large, attractive gabled and shingled Queen Anne-Dutch Colonial-Craftsman home. The widowed Thane Ross Brown, Fred’s first cousin once removed, was a civil engineer, as was his son, Thane Edwin Brown, who worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression. A middle-aged, maiden cousin lived with the two Thanes, serving as their housekeeper. Fred was still employed as a stenographer, now with a detective agency—good background for a future crime writer. The diminutive young man may not have measured up to being an op like gangling hard-boiled crime writer Dashiell Hammett (however much Hammett exaggerated his own detective work), but he would have typed reports the ops made.

After Helen became pregnant with the couple’s first son, James Ross, who was born in 1930, they moved into their own home: an 1100-foot, white picket fenced, dormered cottage at 1534 N. 54th Street, about three miles west of downtown Milwaukee, with two bedrooms and one bathroom. Two years later, their second son, Linn Lewis, was born. The house on 54th Street survives today and appears as an attractive, albeit tiny, abode, painted cream and green and fronted by a white picket fence; though Linn has memories of the four of them living together in a horrid place that “was almost a tenement flat.” This likely was the house at which the family was living in 1940, located at 3437 N. 11th Street, some three miles north of downtown Milwaukee. The lot is now vacant.

In 1932 Fred still had an office job, now as an agent for the New York Life Insurance Company. However, during the Thirties he began working as a proofreader for the Milwaukee Journal and various pulp and trade magazines, for the latter of whom he also wrote articles. Finding that “the stuff he had to read gave him professional nausea,” he pungently recalled to a newspaper in 1956, he concluded that he could write better stuff than the work he was proofing; and he successfully published a half-dozen crime stories between 1937 and 1939. The years of World War Two, in which as a married father in his thirties with bad eyesight and poor all-round health he did not serve, saw an explosion of writing productivity on his part. Between 1940 and 1945 he published over 120 pulp sort stories, mostly crime fiction. He then began writing his first full-fledged crime novel, The Fabulous Clipjoint, in which Ed and Am Hunter made their debuts. The book won an Edgar Award as the best first mystery novel of 1947, encouraging its author finally to quit his editing work and shift fulltime to writing, which was what he had always wanted to do anyway. Twenty-one additional crime novels, five science fiction novels and a single mainstream novel would follow between 1948 and 1963. Additionally, between 1946 and 1965 Fred published more than 140 additional short pieces of fiction, both crime and sci-fi. Now into his middle age, Fred had finally arrived. The show most definitely was on.

*****

Fred and Helen were irretrievably estranged by the Forties and by the time of their divorce in 1947 apparently had not been sexually intimate for years. On his 1940 draft card Fred listed not Helen but her brother Thane, then doing CCC work in the distant town of Tomahawk in northern Wisconsin, as “a person who will know his address.” Fred’s home address is listed as the 11th Street one, but this is crossed over with a red line. Probably by this time Fred had moved out on his family completely, although he continued to support them.

Once he had shut for a final time the familial door, Fred transferred to a room at the Hotel Antlers, located downtown at 616 N. Second Street. This was a men-only establishment, described by author Michail Takach as a “gentlemen’s paradise offering not only 450 fireproof rooms under $2 per day, but also 16 bowling lanes, a 20-table pool hall, golf course, boxing arena, coffee shop, barbershop, cigar lounge and table tennis courts.” Outside there even gleamed a White Tower hamburger restaurant (a rival of White Castle). Takach adds that the Antlers was “[f]illed with 11 floors of single men, usually sailors” and quickly became a place for gay cruising.” The upper floors particularly were known as trysting stations. Whether Fred ever partook of such activities is not known. In any event, the hotel environment at the least would have provided the observant author with plenty of copy for his books.

Parenting and domestic life had never engaged Fred. His son Linn, who held his father in awe, frankly admitted that “Fred Brown wasn’t lovable.” Linn called his father “Fred” because “Fred had instructed me to: ‘Dad’ or ‘Pop’ would have been revolting to him.” When it really came to it, Linn wrote: “Fred didn’t particularly like kids. He couldn’t talk to them…. he told me ‘I never really respected you until you were old enough to stand up at a bar and buy a drink’” and “talk intelligently.”

When still living with his family Fred left Helen to deal with their two boys while he locked himself in a back room and typed or, his son Linn recalled, played “the flute or chess, or more often read.” He loved music and once horrified his wife by bringing home and brandishing an expensive, new Philco radio-phonograph. In one of his 1942 short stories, “Suite for Flute and Tommy-gun,” a character removes himself to “the one room he held sacred” in his house, shutting out his spouse while he plays a flute and piano suite with a friend. “Another man might have set up a blonde,” reflects the narrator. But this man “sought release in pounding ivory.”

Once he had successfully established himself as a crime novelist with the publication of The Fabulous Clipjoint, which netted him not only an Edgar statuette but an eight-book contract with American publisher Dutton, Fred and Helen divorced in 1947. Linn wrote that finally his father could afford the divorce he had desired. Helen moved with their now teenaged sons back to the nicer house on North 54th Street, while Fred provided them with alimony and child support. He also helped pay the boys’ college tuition in the late Forties and early Fifties.

The next year at the age of forty-one Fred married Elizabeth Mary Agnes Charlier, an adventurous divorced stenographer and kindred spirit whom Fred is said to have met at a party. This was no mere dalliance with a sexy younger woman: to the contrary, Beth was forty-six at the time of the marriage, nearly five years older than Fred. She had definitely been around the block a few times, living a life more in accord with the people in Fred’s novels than the rather sheltered, middle-class and to Fred deadly dull and conventional Helen had. One suspects that the new couple’s relationship predated Fred’s divorce and probably helped precipitate it. It is not something that he and Beth would have discussed with the boys.

From the tiny village of Pound in far northeastern Wisconsin, where she was the daughter of a modest farmer of Belgian, presumably Catholic, descent, Beth in the 1920s had moved first to Milwaukee and then to Chicago, an important setting for some of Fred’s crime fiction, such as The Fabulous Clipjoint and The Screaming Mimi. She married her first husband, Norman Herman Schlee, a handsome actor prosaically turned candy store manager, in Chicago in 1932 when she was twenty-eight years old. Blond, blue-eyed, five foot ten and 165 pounds, Schlee was the son of a Milwaukee bartender of German descent. He and Beth in fact had been living together at the Stonehenge Apartment Hotel in Chicago as man and wife for at least a couple of years before they actually got hitched.

The character of Stella Klosterman, the fetching file clerk in The Office, clearly reflects Beth. Brought up by devout Catholic parents on an Athens, Ohio farm, she “seriously considered taking the veil” after graduation from high school, but her life path drastically changed:

Something, she hadn’t known what, had stopped her. Instead she had taken a shorthand typing course in Athens at a commercial school that had just opened there…. She’d decided, without being quite sure why, that she wanted to go to a big city; she’d told her parents it was because opportunities as a stenographer would be better there…. She persuaded her parents to let her go with their blessing. She’d have gone just the same, for she had a will of her own, but she’d managed their acquiescence by a reasonable compromise—Cincinnati. Cincinnati, after all, was still in Ohio, not too far away. New York had been her original idea.

It does not take too keen of a perception to see that Stella’s Athens/Cincinnati/New York stands in for Beth’s Pound/Milwaukee/Chicago. Going one better, in the novel Stella’s first boyfriend, with whom she “satisfied her curiosity” about “actual sex,” is one Herman Reuter—a name which suggests that free-spirited Beth unashamedly told Fred all about her first husband. Having experienced an unsuccessful, if presumably sexually satisfying, relationship with Norman Herman Schlee, Beth seems happily to have settled into something different with diminutive but brilliant Fred Brown. She resembles Nina in Fred’s crime novel The Deep End (1952), a social services worker who had a fling with a studly, blond, football-star high school senior, but has taken up in a serious way with less prepossessing newspaperman Sam Evans.

After Beth and Fred tied the knot, the middle-aged couple lived briefly in New York, where amid much laudation he received his Edgar Award, before moving to artsy Taos, New Mexico in 1949, where they resided for the next three years. The pair then spent a couple of years in California, finally ending up in Tucson, Arizona, where the dry, hot climate was better for Fred’s asthma and allergies. In Tucson in 1956 Fred, who had just published The Lenient Beast, gave some rare publicity, speaking to the Tucson Press Club. In his spectacles resembling a dignified, mid-century college professor, Fred was described in the Tucson Citizen as a “diminutive, sandy-haired author” with a “cookie-duster moustache.” He and Beth lived with their hound dog Duchess at a modest stucco home on South Plumer Avenue,” where Fred spent six months of the year working a few hours a day on a novel, his output having slowed since 1954 to a single crime novel a year. Meanwhile Beth was writing her own book about being married to Fred. (This book, entitled Oh, for the Life of an Author’s Wife, finally saw publication over sixty years later in 2017.) In his spare time there was reading, listening to classical records and playing chess or some hands of poker and bridge.

Except for a couple of years spent in the Los Angeles during the early 1960s, Fred and Beth lived in Tucson until Fred’s death in 1972. In the Fifties Fred’s work—like that of Cornell Woolrich, whom Fred rather resembled in some ways—began to be adapted for television anthology series, including five episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. There was also a 1957 big screen adaption, though sadly a rather poor one, of his novel The Screaming Mimi. A far superior version of the novel (though regrettably uncredited) is the Italian film L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, aka The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, which appeared in 1970, a couple of years before Fred’s death—did he ever come to see or hear of it? More recently a trio of admirable short films has been made from three of Fred’s most wickedly ironic vignettes: Voodoo (2010), The Hobbyist (2016) and The Knock (2018).