Welcome to The Riddler. Every week, I offer up problems related to the things we hold dear around here: math, logic and probability. There are two types: Riddler Express for those of you who want something bite-sized and Riddler Classic for those of you in the slow-puzzle movement. Submit a correct answer for either,1 and you may get a shoutout in next week’s column. If you need a hint, or if you have a favorite puzzle collecting dust in your attic, find me on Twitter.

Riddler Express

From Chris Thornett, a special game of hot potato:

A class of 30 children is playing a game where they all stand in a circle along with their teacher. The teacher is holding two things: a coin and a potato. The game progresses like this: The teacher tosses the coin. Whoever holds the potato passes it to the left if the coin comes up heads and to the right if the coin comes up tails. The game ends when every child except one has held the potato, and the one who hasn’t is declared the winner.

How do a child’s chances of winning change depending on where they are in the circle? In other words, what is each child’s win probability?

Riddler Classic

From Dave Moran, a puzzle perfect for your next work break:

There is a bathroom in your office building that has only one toilet. There is a small sign stuck to the outside of the door that you can slide from “Vacant” to “Occupied” so that no one else will try the door handle (theoretically) when you are inside. Unfortunately, people often forget to slide the sign to “Occupied” when entering, and they often forget to slide it to “Vacant” when exiting.

Assume that 1/3 of bathroom users don’t notice the sign upon entering or exiting. Therefore, whatever the sign reads before their visit, it still reads the same thing during and after their visit. Another 1/3 of the users notice the sign upon entering and make sure that it says “Occupied” as they enter. However, they forget to slide it to “Vacant” when they exit. The remaining 1/3 of the users are very conscientious: They make sure the sign reads “Occupied” when they enter, and then they slide it to “Vacant” when they exit. Finally, assume that the bathroom is occupied exactly half of the time, all day, every day.

Two questions about this workplace situation:

- If you go to the bathroom and see that the sign on the door reads “Occupied,” what is the probability that the bathroom is actually occupied?

- If the sign reads “Vacant,” what is the probability that the bathroom actually is vacant?

Extra credit: What happens as the percentage of conscientious bathroom users changes?

Solution to last week’s Riddler Express

Congratulations to ÑÑÐ⦠Mitchell Breitbart ÑÑÐ⦠of Cambridge, Massachusetts, winner of last week’s Express puzzle and the inaugural inductee into the Ordinal Order of Riddler Nation!

Last week, you were asked to submit a positive integer. The person who submitted the lowest unique number among all submissions won.

The winning number was 85. Mitchell explained his choice thus: The number was high enough that it wouldn’t be too popular, and the fact that it ended in a “5” makes it a round number in a certain way, which other submitters might think to avoid. The logic worked.

Here’s how the nearly 4,000 submissions broke down (zooming in a bit to see just those less than 300):

As arbiter of Riddler Nation, in this induction process I excluded a small set of spammers, including “Arthur from Louisville,” who submitted every single number up to 218 before, apparently, getting bored.

Solution to last week’s Riddler Classic

Congratulations to ÑÑâÐ James Medhurst ÑÑâÐ of Birmingham, England, winner of last week’s Classic puzzle!

You start with the integers from one to 100, inclusive, and you want to organize them into a chain. The only rules for building this chain are that you can only use each number once and that each number must be adjacent in the chain to one of its factors or multiples. For example, you might build the chain 4, 12, 24, 6, 60, 30, 10, 100, 25, 5, 1, 97. You have no numbers left to place after 97, leaving you with a finished chain of length 12. What is the longest chain you can build?

It seems to be 77 numbers long.

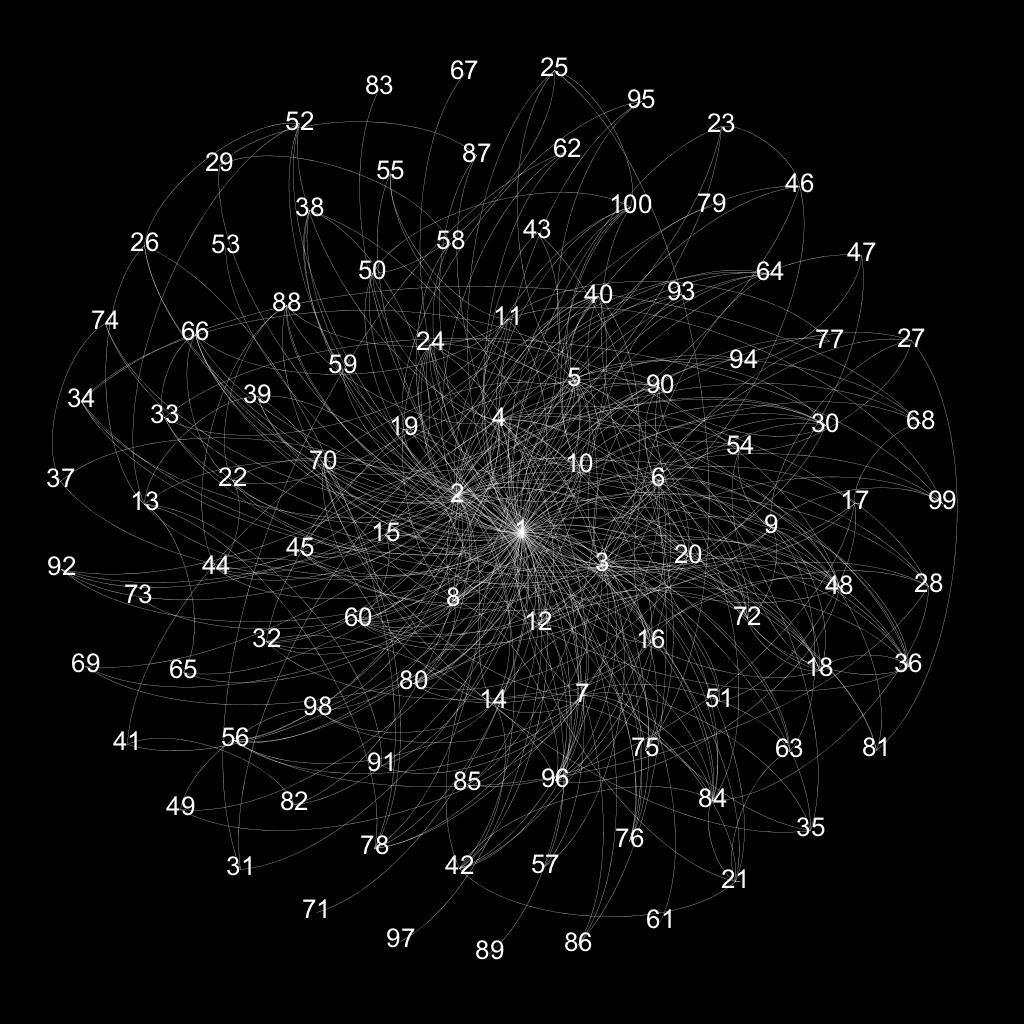

This was a tough one. It’s essentially a “longest path” problem, where the path you’re trying to find is from one number to another to another, with no repeat numbers, and where two numbers are only connected if they are each other’s factor or multiple. Isar Bhattacharjee sent along this illustration:

Problems like this, in general, are called NP-hard — this means there aren’t any known algorithms that can solve it quickly or easily. One solver ran 30 million trials and topped out at a chain of length 55. There does not appear to be a clever pen-and-paper approach, either, beyond taking educated guesses at what might turn into long chains.

But others found computational methods that took them farther down the path. Here’s our winner James’s 77-number-long chain, for example:

93, 31, 62, 1, 87, 29, 58, 2, 92, 46, 23, 69, 3, 57, 19, 38, 76, 4, 68, 34, 17, 85, 5, 35, 70, 10, 100, 50, 25, 75, 15, 45, 90, 30, 60, 20, 40, 80, 16, 64, 32, 96, 48, 24, 12, 6, 78, 26, 52, 13, 91, 7, 49, 98, 14, 56, 28, 84, 42, 21, 63, 9, 81, 27, 54, 18, 36, 72, 8, 88, 44, 22, 66, 33, 99, 11, 55

And here’s solver Anders Kaseorg’s:

62, 31, 93, 3, 69, 23, 46, 92, 4, 76, 38, 19, 95, 5, 65, 13, 52, 26, 78, 6, 48, 96, 32, 64, 16, 80, 10, 70, 35, 7, 49, 98, 14, 56, 28, 84, 42, 21, 63, 9, 81, 27, 54, 18, 36, 72, 24, 12, 60, 30, 90, 45, 15, 75, 25, 50, 100, 20, 40, 8, 88, 44, 22, 66, 33, 99, 11, 55, 1, 87, 29, 58, 2, 68, 34, 17, 85

Other submitters offered arguments that longer chains existed, but none of these arguments were mathematically convincing, and no examples longer than 77 were submitted. Anders found his chain using a small program written in clingo, a language created to solve combinatorial problems, and claimed the program found it to be optimal. Others found their 77s using SageMath or MATLAB.

For extra credit, I called for chains built from the numbers 1 through 1,000. Anders found a specific chain 418 numbers long, although cautioned that that may not be the biggest there can be.

If you alight on any further mathematical insight into this tricky Riddler, let me know!

Want to submit a riddle?

Email me at oliver.roeder@fivethirtyeight.com.