The complex Greek religion that was familiar to the ancient world did not begin with the illustrious Olympian Gods, the group made up of famous deities such as Zeus, Poseidon, Apollo, Aphrodite, Apollo, etc. Indeed, before these gods, named for their home on Mount Olympus ruled, came the Greek Titans, of which there were also twelve.

The transition from the Titans to the Olympians did not, however, happen quietly. Instead, an epic power struggle known as the Titanomachy led to the overthrow of the Titans and reduced them to less significant roles or worse…binding them in the primordial abyss known as Tartarus.

Once great, noble gods were instead diminished to shells of themselves, wallowing in the darkest corners of Tartarus.

However, the tale of the Titans did not end completely with the Titanomachy. In fact, many of the Titans lived on, existing on in Greek mythology vicariously through their kids and through other Olympian gods claiming to be their ancestors.

Table of Contents

Who Were the Greek Titans?

Before we delve into who the Titans were as individuals, we should certainly address who they were as a group. In Hesiod’s Theogony, the original twelve Titans are recorded and known to be twelve children of the primordial deities, Gaia (the Earth) and Uranus (the Sky).

These children were conveniently separated into six male Titans and six female Titans (also referred to as Titanesses, or as Titanides). In the Homeric Hymns, the Titanides are often referred to as the “chiefest of the goddesses.”

In all, the name “Titans” relates back to the superior power, capability, and overwhelming size of these Greek gods. A similar idea is echoed in the naming of the planet Saturn’s largest moon, which is also called Titan for its imposing mass. Their incredible size and strength are unsurprising, considering they were born directly from the union of the huge Earth and the all-encompassing, stretching Sky.

READ MORE: The Greek God Family Tree: A Complete Family Tree of All Greek Deities

Furthermore, they were the siblings of a ton of notable figures in Greek mythology. After all, their mother was the mother goddess in ancient Greece. In that sense, everyone can claim descendence from Gaia. The most significant of these siblings include the Hecatoncheires, the Cyclopes, their father Uranus, and their uncle, Pontus. Meanwhile, their half-siblings included a number of water gods born between Gaia and Pontus.

Siblings aplenty aside, the twelve Greek Titans went on to overthrow their lusty sire to better their own lot in life and ease the sorrow of their mother. Except, that isn’t entirely how things played out.

Cronus – having been the one to physically depose Uranus – seized control of the cosmos. He promptly fell into a paranoid state that left him fearful of being overthrown by his own children. When those Greek gods escaped, rallied by Zeus, the god of thunder, a handful of the Titans fought them in an event known as the Titan War, or the Titanomachy.

The Earth-shaking Titan War led to the rise of the Olympian gods, and the rest is history.

The Greek Titans’ Family Tree

To be completely honest, there is no easy way to say this: the family tree of the twelve Titans is just as convoluted as the entire Greek gods family tree, which is dominated by the Olympians.

Depending on the source, a god could have a completely different set of parents, or an extra sibling or two. On top of that, many relationships within both family trees are incestuous.

Some siblings are married.

Some uncles and aunts are having flings with their nieces and nephews.

Some parents are just casually dating their own kids.

It is just the norm of the Greek pantheon, as it was with a handful of other Indo-European pantheons littered throughout the ancient world.

However, the ancient Greeks didn’t strive to live as the gods did in this aspect of their being. Although incest was explored in Greco-Roman poetry, as in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and in art, the act was still very much seen as a social taboo.

That being said, a majority of the original twelve Titans are married to each other, with Iapetus, Crius, Themis, and Mnemosyne being the meager exceptions. These entanglements made family reunions and the personal lives of the next generation of Greek gods very complicated to follow, especially when Zeus starts to have a say in things.

The 12 Greek Titans

While they are gods themselves, the Greek Titans are distinct from the newer Greek gods (aka the Olympians) that we are more familiar with because they represent the former order. They are the old and archaic; after their collapse from power, new gods took on their roles, and the names of the Greek Titans were all but lost in the pages of history.

However, leave it to Orphism to revive the names of a number of Greek Titans. The term “Orphic” refers to the emulation of the legendary poet and musician, Orpheus, who had dared to defy Hades, the Greek god of death and the underworld, in the myth concerning his wife, Eurydice. The mythical minstrel had descended into the gloom of the Underworld and lived to tell the tale.

On the other side of things, “Orphic” could pertain to the Greek religious movement known as Orphism that emerged during the 7th century BCE. Practitioners of Orphism honored other deities who had gone to the Underworld and returned, such as Dionysus and the goddess of Spring, Persephone.

READ MORE: Dionysus Family Tree: The Lineage of the Greek God of Wine

In an ironic turn of events, the Titans were believed to be the cause of the death of Dionysus, but we’ll get to that later on. (In case you were wondering, Hera might have something to do with this).

Note that a portion of the elder Titans, as the tragedian Aeschylus describes in the masterwork Prometheus Bound, are trapped in Tartarus: “The cavernous gloom of Tartarus now hides ancient Cronus and his allies within it.”

This means that there are very few myths involving the Greek Titans that scholars are aware of post-Titanomachy. Many of the Titans only appear when lineage is drawn to them from existing gods or other entities (like nymphs and monstrosities).

Below you can find all that is known about the original twelve Titans within Greek mythology, whose power challenged that of the Olympians and who, for a time, ruled the cosmos.

Oceanus: God of the Great River

Leading in with the eldest child, let us present Oceanus. This Titan god of the great river – also named Oceanus – was married to his younger sister, the sea goddess Tethys. Together they shared the Potamoi and the Oceanids.

In Greek mythology, Oceanus was believed to be a massive river that encircled the Earth. All fresh and saltwater came from this single source, which is reflected in his children, the 3,000 river gods collectively called the Potamoi. Once the idea for Elysium was conceived – an afterlife where the righteous went – it was established to be on the banks of Oceanus at the ends of the Earth. On the flip side of things, Oceanus also had influence over regulating heavenly bodies that would set and rise from his waters.

During the Earth-shaking Titanomachy, Hesiod claimed that Oceanus sent his daughter, Styx, and her offspring to fight Zeus. On another hand, the Iliad details that Oceanus and Tethys stayed out of the Titanomachy and harbored Hera during the 10-year war. As stand-in parents, the pair did their best to teach Hera how to hold her temper and act rationally.

We can see how well that went.

Many surviving mosaics depict Oceanus as a bearded man with long, occasionally curly, salt-pepper hair. The Titan has a set of crab pincers erupting from his hairline and a stoic look in his eye. (Oh, and in case the crab claws didn’t scream “water god,” then his fish-like lower body certainly will). His authority is represented by the trident he wields, which provokes the imagery of both the ancient sea god Pontus and Poseidon, whose influence came with the power of the new gods.

READ MORE: Oceanus: The Titan God of the River Oceanus

Coeus: God of Intelligence and Inquiry

Known as the Titan god of intelligence and inquiry, Coeus married his sister, Phoebe, and together the pair had two daughters: the Titanesses Asteria and Leto. Furthermore, Coeus is identified with the Northern Pillar of the Heavens in Greek mythology. He is one of four brothers that held down their father when Cronus castrated Uranus, solidifying their loyalty to their youngest brother and future king.

The Pillars of the Heavens in Greek cosmology are the northern, southern, western, and eastern corners of the Earth. They keep the sky aloft and in place. It was up to the Titan brothers – Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, and Iapetus – to support the Heavens during Cronus’ reign until Atlas was sentenced to bear the weight of it on his own following the Titanomachy.

In fact, Coeus was one of the many Titans that sided with Cronus during the Titanomachy, and he subsequently got banished to Tartarus with the others who stayed loyal to the old power. Due to his unfavorable loyalty and eternal imprisonment, there are no known effigies of Coeus that exist. However, he does have an equal in the Roman pantheon named Polus, who is the embodiment of the axis that heavenly constellations revolve around.

As an aside, both of his daughters are listed to be Titans in their own rights – an identity that carries on largely with other offspring of the primary twelve children of Gaia and Uranus. Despite their father’s troublesome allegiance throughout Greek mythology, both daughters were romantically pursued by Zeus after the fall of the Titans.

READ MORE: Zeus Family Tree: The Family Tree of the King of the Gods

Crius: God of Heavenly Constellations

Crius is the Titan god of heavenly constellations. He was married to his half-sister, Eurybia, and was the father of the Titans Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.

Much like his brother Coeus, Crius was charged with supporting a corner of the Heavens, representing the Southern Pillar until the Titanomachy. He fought against the rebelling Olympians with his Titan brothers and was also subsequently imprisoned in Tartarus when all was said and done.

Unlike many other gods within the pantheon, Crius is not a part of any redeeming myth. His mark on the Greek world lies with his three sons and prestigious grandchildren.

Beginning with the oldest son, Astraeus was the god of dusk and wind, and the father of the Anemoi, Astrea, and the Astra Planeta by his wife, the Titan goddess of dawn, Eos. The Anemoi were a set of four wind deities that included Boreas (the north wind), Notus (the south wind), Eurus (the east wind), and Zephyrus (the west wind), whereas the Astra Planeta were literal planets. Astrea, their uniquely individualistic daughter, was the goddess of innocence.

Next, the brothers Pallas and Perses were marked by their brute strength and affinity for violence. Specifically, Pallas was the Titan god of war and warcraft and was the husband of his cousin, Styx. The pair had a number of children, ranging from the personified Nike (victory), Kratos (strength), Bia (violent anger), and Zelus (zeal), to the more malicious monstrosity, the serpentine Scylla. Also, since Styx was a river that flowed through the Underworld, the couple also had a number of Fontes (fountains) and Lacus (lakes) as children.

Lastly, the youngest brother Perses was the god of destruction. He married their other cousin, Asteria, who gave birth to Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft and crossroads.

Hyperion: God of Heavenly Light

Next up on our titanic list is the god of sunlight himself, Hyperion.

Husband to his sister Thea and father to the sun god, Helios, the moon goddess Selene, and the goddess of dawn Eos, Hyperion is interestingly enough unmentioned in the accounts of the Titanomachy. Whether or not he participated on either side or remained neutral is unknown.

Perhaps Hyperion, being the god of light, had to stay out of imprisonment from an ancient Greek religious standpoint. In the end, how would you explain the sun still shining outside if the god of light was trapped in no-man’s-land beneath the Earth? That’s right, you wouldn’t (unless Apollo comes into the picture).

That being said, he was another one of the Pillars of the Heavens and although it is not clearly stated as to which he has domain over, many scholars speculate that he had control over the East: a belief largely influenced by his daughter being the dawn sky. His support of a Pillar is enough evidence to theorize that Hyperion followed the trend of the others siding with Cronus during the Titanomachy. This hypothetical imprisonment would be the reason why the younger Apollo took the helm of being the god of sunlight.

READ MORE: Hyperion: Titan God of Heavenly Light

Iapetus: God of the Moral Life-cycle

Iapetus is the Titan god of the mortal life cycle and, possibly, craftsmanship. Supporting the Western Heavens, Iapetus was the husband of the Oceanid Clymene and the father of Titans Atlas, Prometheus, Epimetheus, Menoetius, and Anchiale.

The influence Iapetus held over mortality and craft is reflected in the faults of his children, who themselves – at least Prometheus and Epimetheus – were thought to have had a hand in creating mankind. Both Titans are craftsmen themselves, and although they are full of affection, each is entirely too cunning or entirely too foolish for their own good.

For example, Prometheus, in all his guile, gave mankind sacred fire, and Epimetheus willingly married Pandora known for Pandora’s box after being specifically warned not to.

Furthermore, much like Coeus and Crius – possibly Hyperion as well – Iapetus was believed to be fiercely loyal to Cronus’ rule. This fanaticism rubbed off on his sons Atlas and Menoetius, who fervently fought and fell during the Titanomachy. While Atlas was forced to suspend the Heavens on his shoulders, Zeus struck down Menoetius with one of his thunderbolts and trapped him in Tartarus.

As far as looks go, there are some statues that are believed to be done in Iapetus’ likeness – most showing a bearded man cradling a spear – although none are confirmed. What often happens is that most of those Titans who were trapped in the murky gloom of Tartarus are not popularly followed, therefore they are likely not immortalized as is seen with Oceanus.

READ MORE: Iapetus: Greek Titan God of Mortality

Cronus: God of Destructive Time

Finally presenting Cronus: the baby brother of the Titan brood and, arguably, the most infamous. Of the original twelve Greek Titans, this Titan god certainly has the worst reputation in Greek mythology.

Cronus is the god of destructive time and was married to his sister, the Titaness Rhea. He fathered Hestia, Hades, Demeter, Poseidon, Hera, and Zeus by Rhea. These new gods will eventually be his undoing and take the cosmic throne for themselves.

Meanwhile, he had another son with the Oceanid Philyra: the wise centaur Chiron. One of the few centaurs to be acknowledged as civilized, Chiron was celebrated for his medicinal knowledge and wisdom. He would train a number of heroes and act as counsel for numerous Greek gods. Also, as the son of a Titan, Chiron was effectively immortal.

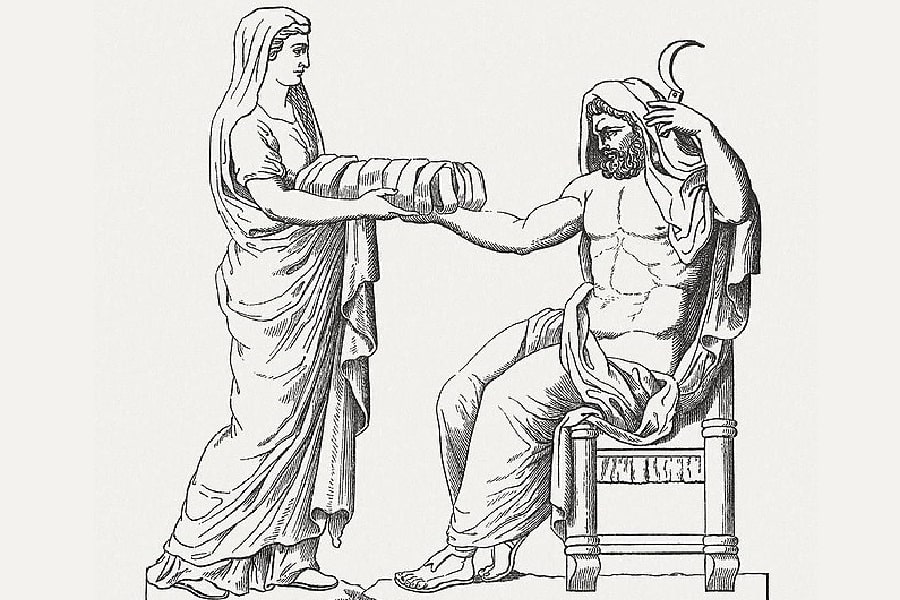

In his most famous myths, Cronus is known as the son that castrated and deposed his old man, Uranus, after Gaia gave Cronus the adamantine sickle. In the time thereafter, Cronus ruled the cosmos during the Golden Age. This period of prosperity was recorded to be the golden age of mankind, since they knew no suffering, harbored no curiosity, and obediently worshipped the gods; it predated the far more lack-luster ages when man became familiar with strife and distanced themselves from the gods.

On the other side of things, Cronus is also known as the father that ate his infant children – except the infant Zeus, of course, who escaped when his father instead swallowed a rock. The compulsion began when he realized that he, too, could be usurped by his children.

Since his youngest son escaped ingestion, Zeus freed his siblings after poisoning Cronus and triggered the start of the Titanomachy. He similarly freed his uncles, the Cyclopes – giant one-eyed beings – and the Hecatonchires – giant beings with fifty heads and a hundred arms – to help change the tides of the war in his favor.

In spite of the superior strength of the Titan god and his scattered allies, the Greek gods prevailed. The transfer of power wasn’t entirely a clean one, with Zeus chopping up Cronus and throwing him, along with four of the original twelve Titans, into Tartarus for their participation in the war. From that point on, it was officially the Olympian gods who ruled the cosmos.

In the end, it was Cronus’ own obsession with power that led to the fall of the Titans. After the Titanomachy, little is recorded of Cronus, although some later variations of mythology cite him as being forgiven by Zeus and permitted rule over Elysium.

READ MORE: Cronus: The Titan King

Thea: Goddess of Sight and the Shining Atmosphere

Thea is the Titan goddess of sight and of the shining atmosphere. She was the wife of her brother, Hyperion, and as such is the mother of the shining Helios, Selene, and Eos.

What’s more is that Thea is frequently associated with the primordial deity, Aether, frequently being identified as a feminine aspect of him. Aether, as one could probably guess, was the bright upper atmosphere in the sky.

On that note, Thea is also identified with another name, Euryphaessa, which means “wide-shining” and likely denotes her position as the feminine translation of primordial Aether.

As the eldest of the Titanides, Thea was well-respected and revered, referenced admirably in the Homeric hymn for her son as “mild-eyed Euryphaessa.” Her consistently gentle temper is a trait that is notably valued in ancient Greece and, honestly, who doesn’t love a bright, clear sky?

Saying that Thea did not only light up the sky. It was believed that she granted precious gems and metals their luster, much like she granted her celestial children theirs.

Unfortunately, no complete images of Thea survive, however, she is believed to be depicted in the Pergamon Alter’s frieze of the Gigantomachy, fighting beside her son, Helios.

As with many other Titanades, Thea had the gift of prophecy inherited from her mother, Gaia. The goddess held influence amongst oracles in ancient Thessaly, with a shrine dedicated to her at Phiotis.

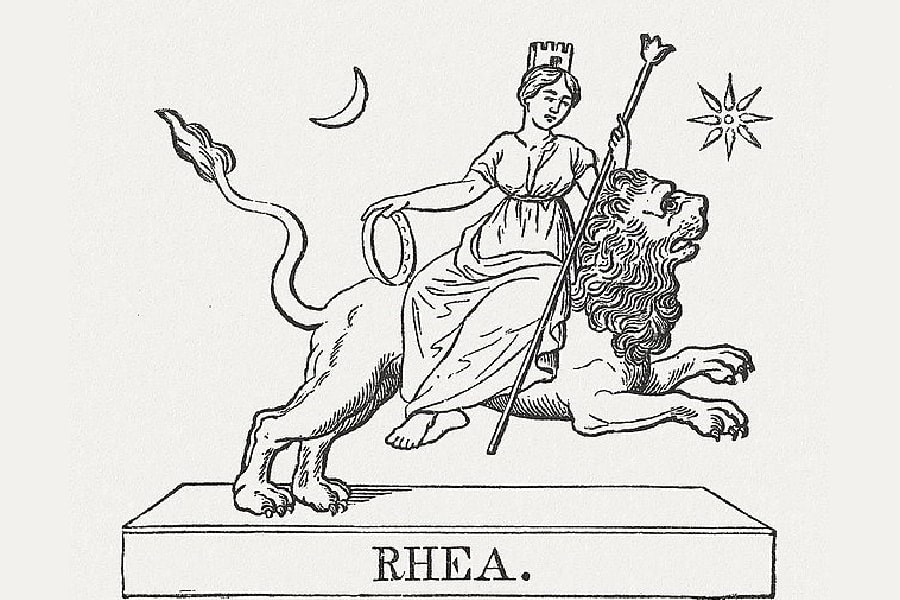

Rhea: Goddess of Healing and Childbirth

In Greek mythology, Rhea is the wife of Cronus and the mother of the six younger gods that eventually overthrew the Titans. She is the Titan goddess of healing and childbirth, having been known to ease labor pains and a multitude of other illnesses.

Despite her many accomplishments as a goddess, Rhea is best known in mythology for deceiving her husband, Cronus. Unlike the usual kind of scandal associated with the Greek gods, this deception was far tamer in comparison. (After all, how could we possibly forget Aphrodite and Ares getting caught in a net by Hephaestus)?

As the story goes, Cronus started swallowing his children after some prophecy granted by Gaia, which drove him to an unshakable state of paranoia. So, sick of having her children routinely taken and eaten, Rhea gave Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes to swallow instead of her sixth and final son, Zeus. This rock is known as the omphalos stone – translated as the “navel” stone – and depending on you ask, it could be as big as a mountain or as big as a standard hefty rock found in Delphi.

Furthermore, for Rhea to save her son, she had him harbored in a cave in Crete, the land once ruled by King Minos, until young adulthood. Once he was able to, Zeus infiltrated Cronus’ inner circle, freed his siblings, and started a great war that lasted 10 years to determine once and for all who truly ruled the cosmos. Since she stayed out of the Titanomachy, Rhea survived the war and, as a free woman, resided in a palace in Phrygia. Her residency is largely connected to the Phrygian mother goddess, Cybele, with whom she was routinely associated with.

In separate tales involving Rhea, after his second birth, an infant Dionysus was given to the great goddess by Zeus for her to raise. More or less, the King of the Gods was anticipating his jealous wife, Hera, tormenting the illegitimate child.

Which, props can be given to Zeus for thinking ahead, but alas, Hera has her ways. When grown, Dionysus was afflicted with madness by the goddess of marriage. He wandered the land for several years until his adoptive mother, Rhea, cured his affliction.

Contrarily, it is also said that Hera had thrown Dionysus to the Titans after his first birth, which led to them tearing apart Dionysus. Rhea had been the one to pick up fragments of the young god to allow him to be reborn.

READ MORE: Rhea: The Mother Goddess of Greek Mythology

Themis: Goddess of Justice and Counsel

Themis, also fondly known as Lady Justice nowadays, is a Titan goddess of justice and counsel. She interpreted the will of the gods; as such, her word and wisdom went unquestioned. According to Hesiod in his work, Theogony, Themis is the second wife of Zeus after he ate his first wife, the Oceanid Metis.

Now, while Themis may be represented by a blindfolded woman holding scales today, it is a little extreme to think something as insane as her love-interest nephew eating his wife – also her niece – went unnoticed. Wasn’t that the reason they overthrew Cronus? Because he started eating others in the name of maintaining a long-lasting reign?

Ahem.

Anyways, after Themis married Zeus, she gave birth to the three Horae (the Seasons) and, occasionally, the three Moirai (the Fates).

As with many of her sisters, she was a prophetess with a once-mass following at Delphi. Her Orphic hymn denotes her as the “beauteous-eyed virgin; first, from thee alone, prophetic oracles to men were known, given from the deep recesses of the fane in sacred Pytho, where renowned you reign.”

Pytho, an archaic name for Delphi, was the seat of the Pythian priestesses. In spite of the fact that Apollo is more commonly associated with the location, Greek mythology lists Themis as having organized the construction of the religious center, with her mother, Gaia, serving as the first prophetic god to relay messages to the oracle.

READ MORE: Themis: Titan Goddess of Divine Law and Order

Mnemosyne: Goddess of Memory

The Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne is best known to be the mother of the nine Muses by her nephew, Zeus. It is well known that the mind is a powerful thing and that memories themselves hold immense power. More than that, it is a memory that permits the development of creativity and imagination.

In her own Orphic hymn, Mnemosyne is described as the “source of the holy, sweet-speaking Nine,” and further as “all-powerful, pleasant, vigilant, and strong.” The Muses themselves are famed for their influence on the innumerable creatives in ancient Greece, as an individual’s font of inspiration inevitably relied on the kindness imposed by the Muses.

For example, have you ever found yourself suddenly struck by inspiration, but then when you go to write down whatever grand idea you had, you forget just what it was? Yeah, we can thank Mnemosyne and the Muses for that. So, although her daughters can be the source of a great idea or two, Mnemosyne can just as easily torment the poor souls of the very artists that revere them.

Yet, tormenting artists isn’t all Mnemosyne was known for. In the dark gloom of the Underworld, she oversaw a pool that bore her name near the river Lethe.

For some background, the dead would drink from Lethe to forget their past lives when reincarnated. It was a crucial step in the transmigration process.

Beyond this, those that practiced Orphism were encouraged that, when faced with a decision, they should instead drink from Mnemosyne’s pool to stop the reincarnation process. Since the souls remember their previous lives, they would not successfully be reincarnated, thus defying the natural order of things. The Orphics desired to break from the cycle of reincarnation and to live eternally as souls in the veil between the world as we know it and the Underworld.

In this sense, drinking from Mnemosyne’s pool was the most important step to take after death for an Orphic.

READ MORE: Mnemosyne: Goddess of Memory, and Mother of The Muses

Phoebe: Goddess of Shining Intellect

Phoebe was the Titan goddess of shining intellect and held close associations with the moon thanks to her granddaughter, Artemis, of whom oftentimes took the identity of her much-beloved grandmother. The practice was also adopted by Apollo, who was called by the masculine variation, Phoebus, on a number of occasions.

READ MORE: Apollo Family Tree: The Lineage of the Greek God of Light

Phoebe is the wife of Coeus and the devoted mother of Asteria and Leto. She stayed out of the conflict of the Titan War, thus being spared punishment in Tartarus, unlike her husband.

To reiterate, many female Titans were endowed with the gift of prophecy. Phoebe was no exception: two out of three of her grandchildren, Hecate and Apollo, procured some degree of inherent prophetic ability as well.

At some point, Phoebe even held court at the Oracle of Delphi: a role granted to her by her sister, Themis. After she gifted the Oracle of Delphi to Apollo, the acclaimed “Center of the World” remained an oracular hotspot.

In later Roman mythology, Phoebe is closely associated with Diana, as the lines became blurred on who was constituted as a lunar goddess. Similar confusion occurs when distinguishing Selene from Phoebe; from Artemis (who, conveniently, is also called Phoebe); from Luna, and from Diana in other general Greco-Roman practices.

Tethys: Mother of the River Gods

Tethys is the wife of Oceanus and the mother of a number of powerful deities, including the plentiful Potamoi and the opulent Oceanids. As the mother of river gods, sea nymphs, and cloud nymphs (a portion of Oceanids known as the Nephelai), her physical influence was felt across the Greek world.

By virtue of Hellenistic Greek poetry, she is most frequently granted attributes of a sea goddess, even if much of her realm of influence is restricted to underground wells, springs, and freshwater fountains.

READ MORE: Who Invented Water? History of the Water Molecule

Again, the general consensus is that Tethys and her husband, Oceanus, stayed out of the Titanomachy. The limited sources that do cite the couple as getting involved relate them to adopting the Olympian plight, therefore placing themselves in direct opposition to their otherwise domineering siblings.

There are a number of mosaics of Tethys that have survived, depicting the Titaness as being a beautiful woman with dark flowing hair and a set of wings at her temple. She is seen with gold earrings and with a serpent coiled around her neck. Usually, her visage would decorate the walls of public baths and pools. At the Zeugma Mosaic Museum in Gaziantep, Turkey, 2,200-year-old mosaics of Tethys and Oceanus have been unearthed alongside the mosaics of their nieces, the nine Muses.

READ MORE: Tethys: Grandmother Goddess of the Waters

Other Titans in Greek Mythology

Despite the above twelve Titans being the most well-recorded, there were in fact other Titans known around the Greek world. They were varied in the role, and many are of little renown outside of being a parent of a larger player in mythology. These younger Titans, as they are frequently called, are the second generation of older gods that remains ever-still distinct from the new Olympian gods.

Granted that many of the younger Titans are touched on in the above sections, here we will review those progeny that were not mentioned.

Dione: The Divine Queen

Recorded occasionally as the thirteenth Titan, Dione is frequently depicted as an Oceanid and an Oracle at Dodona. She was worshipped alongside Zeus and oftentimes interpreted to be a feminine aspect of the supreme deity (her name translates roughly to “divine queen”).

In many myths that she is included in, she is recorded to be the mother of the goddess Aphrodite, born from an affair with Zeus. This is primarily mentioned in the Iliad by Homer, while Theogony notes her to be merely an Oceanid. Contrarily, some sources have Dione listed as the mother of the god Dionysus.

READ MORE: Aphrodite Family Tree: A Family of the Greek Goddess of Love

Eurybia: Goddess of the Billowing Winds

Eurybia is mentioned as the half-sister wife of Crius, though she is additionally classified as a Titan in mythology. As a minor Titan goddess, she is the daughter of Gaia and the sea deity Pontus, who granted her mastery of the seas.

More specifically, Eurybia’s heavenly powers allowed her to influence the billowing winds and shining constellations. Ancient sailors surely would have done their best to appease her, although she is scarcely referenced outside of her maternal relation to the Titans Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.

Eurynome

Originally an Oceanid, Eurynome was the mother of the Charities (the Graces) by her cousin, the supreme god Zeus. In mythology, Eurynome is sometimes noted as Zeus’ third bride.

The Charities were a set of three deities that were members of the entourage of Aphrodite, with their names and roles changing throughout Greek history.

Lelantus

Lesser known and strongly debated, Lelantus was the speculated son of the Greek Titans Coeus and Phoebe. He was the god of the air and of unseen forces.

It is unlikely that Lelantus participated in the Titanomachy. Not much is known of this deity, outside of him having a better-known daughter, the huntress Aura, Titan goddess of the morning breeze, who had garnered the ire of Artemis after making a remark about her body.

Following the story, Aura was exceedingly proud of her virginity and claimed that Artemis appeared “too womanly” to truly be a virginal goddess. As Artemis immediately reacted out of wrath, she reached out to the goddess, Nemesis, for retribution.

As a result, Aura was assaulted by Dionysus, tormented, and driven mad. At some point, Aura gave birth to twins from the earlier assault by Dionysus and after she ate one, the second was rescued by none other than Artemis.

The child was named Iacchus, and became a loyal attendant to the harvest goddess, Demeter; he reportedly played a vital role in commencing the Eleusinian Mysteries, when sacred rites in honor of Demeter were annually performed on Eleusis.

Who Were Ophion and Eurynome?

Ophion and Eurynome were, following a cosmogony penned by Greek thinker Pherecydes of Syros sometime in 540 BCE, Greek Titans that ruled the Earth prior to the ascension of Cronus and Rhea.

In this variation of Greek mythology, Ophion and Eurynome were presumed to be the eldest children of Gaia and Uranus, though their true origin is not explicitly stated. This would make them an additional two to the original twelve Titans.

Additionally, the pair did reside on Mount Olympus, much like the familiar Olympian gods. As Pherecydes recalls, Ophion and Eurynome were cast into Tartarus – or into Oceanus – by Cronus and Rhea who, according to the Greek poet Lycophron, was excellent at wrestling.

Outside of the largely missing accounts from Pherecydes, Ophion, and Eurynome are not generally mentioned in the rest of Greek mythology. Nonnus of Panopolis, a Greek epic poet during Rome’s imperial era, does refer to the couple through Hera in his 5th century AD epic poem, Dionysiaca, having the goddess imply that both Ophion and Eurynome resided in the depths of the ocean.