by Su Xinqi

Three decades after he landed on Hong Kong shores as a child refugee, Vo Van Hung is fighting efforts to deport him to Vietnam now that he has finished a lengthy jail sentence — for murder.

Vietnam’s “boat people” exodus subsided years ago. But Vo, 41, is one of just a handful of remaining refugees whose fate remains undecided.

And his battle against deportation dredges up memoirs of a grim chapter in Hong Kong’s recent history.

Since arriving in Hong Kong as a 12-year-old unaccompanied refugee in 1991, Vo has spent his life behind barbed wire and then bars.

He was first housed in a notoriously violent refugee camp where tens of thousands of Vietnamese were placed, often for years, until their cases were decided — most with eventual asylum in other countries.

But Vo soon ended up in prison — for 22 years — after he was convicted as a teenager of murdering a fellow camp inmate during an argument.

Since completing his jail term four years ago he has been held at an immigration centre pending deportation, a move he is fighting in the courts.

“If they send me back to Vietnam I would rather be locked up here for the rest of my life,” he told AFP behind a plexiglass barrier separating inmates and visitors.

“I have no family and friends in Vietnam.”

Dangerous sea voyages

In the years after the Vietnam War ended some 200,000 Vietnamese arrived in Hong Kong fleeing poverty and persecution by the victorious communists.

Most made desperately dangerous voyages across the South China Sea on crammed and rickety boats — a method that earned the demographic their moniker.

By the time the last refugee camps were closed in 2000 some 144,000 Vietnamese were resettled in third countries, 58,000 were repatriated and just 1,400 were allowed to integrate locally.

Prisoners remained something of a grey area.

In 2003, city authorities said 15 Vietnamese inmates were eligible to stay in Hong Kong on completion of their sentence, while 18 others would be deported.

Vo, who now speaks Cantonese better than Vietnamese, was never told what his status was.

So when he walked out of prison in 2016, he expected to be a free man.

He got as far as the prison gate.

“A number of immigration officers waiting there handcuffed me and told me I would be taken to the detention centre,” he recalled.

Two years ago he won a judicial review against the immigration department’s initial decision to deport him.

A second immigration hearing is imminent but has been delayed by court closures during the coronavirus outbreak.

Hong Kong’s government declined to comment on Vo’s case.

The Security Bureau said there are currently 18 Vietnamese nationals who have been deemed ineligible for local resettlement for various reasons including imprisonment.

Vo argues he might be subject to political persecution if he was repatriated because his biological father was a South Vietnamese soldier who fled overseas and left him in the care of the adoptive parents who then sent him alone to Hong Kong.

He also fears being prosecuted a second time for the murder in the refugee camp.

Asked about that killing he replied: “I certainly regret it. I did not know how to behave properly. [Violence was] my only way to protect myself and others.”

Riots and rape

The camp — on a remote cape called “Whitehead” — was a rough place, with violence and rape commonplace.

“People were fighting for everything all the time,” he recalled.

Hunger strikes and riots that broke out in 1994 and 1996 were only ended when Hong Kong — then ruled by Britain — sent in tear gas wielding police via helicopters and armoured trucks.

Supporters of Vo say he reformed within prison, learning skills like book-keeping, hair-styling and sewing.

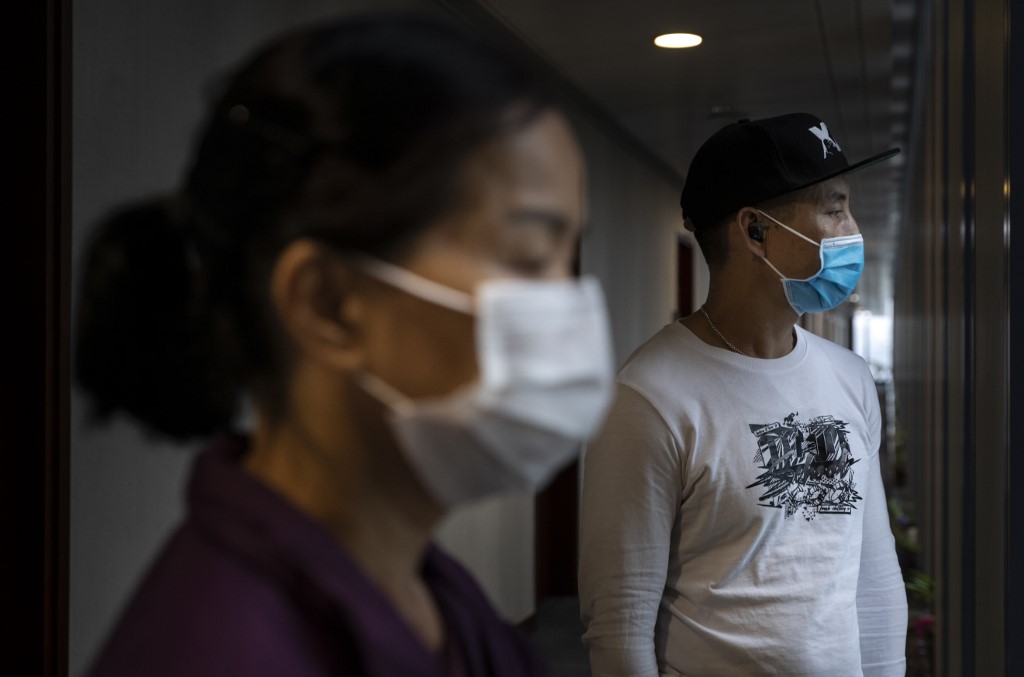

In the immigration detention centre Vo says he spends his time using his Cantonese to help fellow refugees fill out paperwork.

Vu Van Lao, an ex-convict and former Vietnamese refugee, has been a friend of Vo for nearly two decades since they met in prison.

“Vo has learned to behave after he grew up and studied in prison. Why can’t he be given a chance?” Vu told AFP.

Vu was given the chance to settle in Hong Kong after his sentence and became a construction worker.

Asked what deportation would mean for Vo, Vu replied: “It would be another sentence of life imprisonment.”