You could say that 2024 has been a perfect year for exhibitions. Certainly, it struck the right note between landmark celebrations, such as the National Gallery’s Van Gogh blockbuster, and new discoveries, such as Peggy Guggenheim’s little-known sojourn in the English countryside, or the work of pioneering photojournalist Bert Hardy at The Photographers’ Gallery.

There have been some duds too of course, and an outstandingly dire shortlist confirmed the Turner Prize’s unenviable reputation as a national joke. Here, as with Tate Britain’s new exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain, a sense of humour failure and an obsession with identity politics took its toll. But curators take note: issue-led exhibitions, and even a didactic element, can be fresh, revelatory and inspiring, as seen at Tate Modern’s Zanele Muholi survey, the National Gallery’s Hockney x Piero collab, and the Barbican’s look at modern India, all on this list. Brave is good, and this year’s best shows have all in some way broken the mould.

10. Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, Turner Contemporary, Margate

In the decades following the Second World War, the 50 or so women in this exhibition seized on abstraction as a fresh new visual language that, relatively untainted by gender and tradition, was still to be shaped and explored. Curated to reveal patterns of thinking, looking and making at a time of huge political and social change, the exhibition brought famous names like Barbara Hepworth and Elizabeth Frink together with less familiar figures from all over the world. For Slovakian sculptor Mária Bartuszová, the ambiguities of abstraction afforded her freedom of expression under totalitarian rule. Maria Merz’s Living Sculpture, made from strips of aluminium foil still spattered with cooking fat from her Turin kitchen, remains a bold and inspiring statement of freedom from deep in the trenches of domestic duty.

9. Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern

Cut short by Covid, Tate Modern’s career-spanning survey of the South African photographer and visual activist Zanele Muholi was so popular that it came back for a second outing, updated with new works, including sculptures. Ncinda (2023), a vast bronze representation of the clitoris, was memorable, ambitious but ultimately disappointing, though it took nothing away from the rest of the show, a tender, brutal rollercoaster ride through the peaks and troughs of humanity’s ugliest and most beautiful aspects. Switching easily between the lexicons of reportage, portraiture, the taxonomic projects of the colonial era and fashion photography, Muholi skewers and documents the experiences of queer Black South Africans with painful, tender clarity, and her magisterial, ongoing project Somnyama Ngonyama is already one of the great works of self-portraiture.

To 26 January 2025 (tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/zanele-muholi)

8. Peggy Guggenheim: Petersfield to Palazzo, Petersfield Museum and Art Gallery

In the five years before the outbreak of the Second World War, the American heiress known best for her Venetian palazzo, her prodigious appetite for men, and her pledge to buy “a painting a day” was living the quiet life just outside the market town of Petersfield on the West Sussex-Hampshire border. Deep in the English countryside she found solace from a series of personal crises, and set in motion the plans that would cement her reputation as one of the great collectors and patrons of the 20th century. Weaving local newspaper reports and archival research with loans from the Guggenheim Museum in Venice this was a feat of dogged, ambitious and imaginative research – neither Guggenheim nor Petersfield will look quite the same again.

7. Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look, National Gallery, London

The National Gallery’s bicentenary year was a chance to reflect on its role not just as a place for the public to enjoy the peerless national collection, but as an incomparable resource for artists. Who better to make the point than David Hockney, whose status as a national treasure is easily equal to that of the gallery itself. Comprising just three paintings, this exhibition was a passionate and elegantly argued case for looking at pictures carefully, in which Hockney’s personal, lifelong relationship with Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ revealed much about the special qualities of that painting and explored how pictures and the National Gallery can nurture a rich interior life.

6. The World of Tim Burton, The Design Museum, London

Without wanting to sound either ancient or technophobic, sometimes the simple act of putting pencil to paper can feel as laughably primitive as rubbing sticks together to make fire. This is especially so in the film world, which is never not pushing at the frontiers of technology, making the Design Museum’s retrospective on maverick auteur Tim Burton extra special. Though Burton has embraced technology, his love of stop-motion animation has persisted, and all of his ideas, from the monsters of his childhood imagination to Jack Skellington and Edward Scissorhands, began as drawings – and not always terribly good ones. With its comprehensive displays of designs, puppets, costumes and storyboards from Mars Attacks! to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, this is a cast-iron crowd pleaser.

To April 2025 (designmuseum.org/exhibitions/the-world-of-tim-burton)

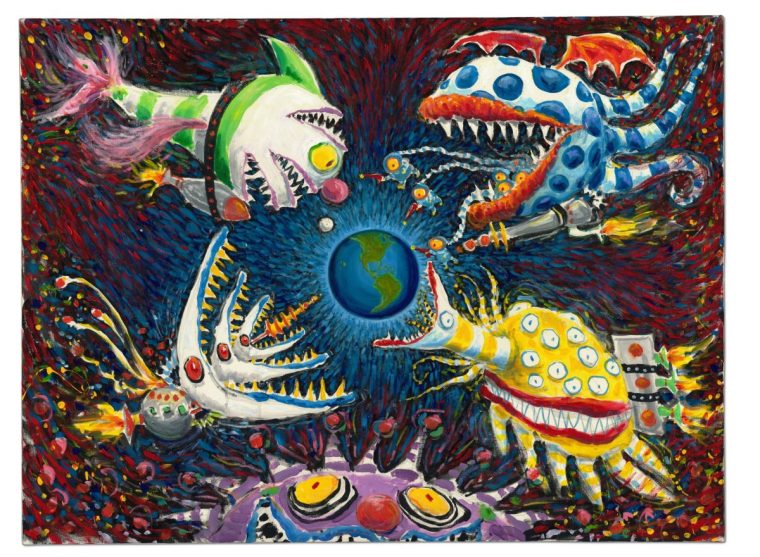

5. The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998, Barbican Art Gallery, London

Call me old-fashioned but it’s not often that an exhibition asks viewers to put real effort in: this one absolutely does, and in a good way. Free from labels and wall texts, around 150 paintings, sculptures, photographs, installations and films by 30 artists present a panoramic view of a country in uproar, transformed by rapid urbanisation, social change and economic instability. Framed by Indira Gandhi’s 1975 declaration of a state of emergency, and another calamitous assault on liberty and peace, the Pokhran Nuclear Tests in 1998, this is an exhilarating testament to art as a rallying call, a response to crisis, and a way of articulating a better future.

To 5 January 2025 barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2024/event/the-imaginary-institution-of-india-art-1975-1998)

4. SUNLIGHT: Roger Ackling, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery

You’ve probably never heard of Roger Ackling – few people have, but once you’ve seen this beautiful, lovingly curated show you’ll never forget him. A true British eccentric, Ackling’s studio was the beach at Weybourne in Norfolk, where he would sit for hours, scorching patterns into driftwood by directing sunlight through a magnifying glass, a productive day’s work registering on his body as peculiar patches of sunburn. Ackling went through life gently, working with found materials – driftwood, elastic bands, lolly sticks – to create haunting, otherworldly works of art. An exceptional teacher, he was recognised as a fellow traveller by Italy’s Arte Povera artists, his affinities with land artists like Hamish Fulton and Richard Long cemented in their collaborative works, and longstanding friendship.

Transferring to Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 4 April-22 June 2025 (henry-moore.org/whats-on/sunlight-roger-ackling)

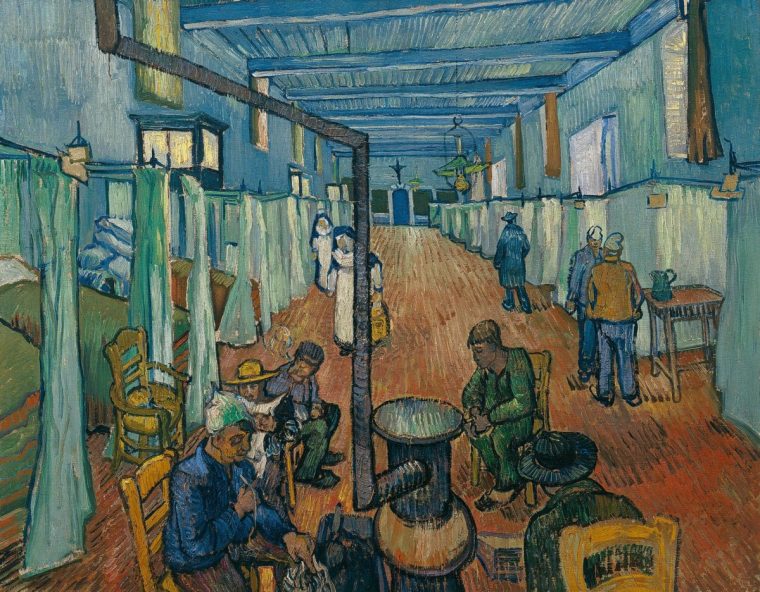

3. Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, 2025 National Gallery, London

Amazingly, this is the first time the National Gallery has dedicated an exhibition to Vincent Van Gogh, the beloved painter of some of its most famous pictures, including Sunflowers, and Van Gogh’s Chair, which the Gallery bought exactly 100 years ago. There could have been no more fitting choice to mark the climax of the Gallery’s bicentenary celebrations, and this selection of some of Van Gogh’s best loved pictures from around the world – The Yellow House (The Street), and La Berceuse among them – is a joyous reminder of his unique talent. It’s more than that though – focusing on the last two years of the artist’s life as a period of ambitious and optimistic creative flowering, rejecting the mawkish sense of foreboding that is habitually attached to these years.

To 19 January 2025 (nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/van-gogh-poets-and-lovers)

2. Bert Hardy: Photojournalism in War and Peace, The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Chances are you’ll know at least one of Bert Hardy’s photos, even if you didn’t know he took them. Those two cheeky boys from the Gorbals, perhaps? Or the girls on Blackpool promenade, skirts billowing? As the star lensman on Picture Post magazine, Hardy covered everything from the Blitz to the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, boxing matches to chatting fishwives in Hull, but he never achieved the fame of contemporaries like Bill Brandt, or the Magnum photographer Robert Capa. This was a much needed corrective, and a chance to see some of the defining photographs of the mid 20th century.

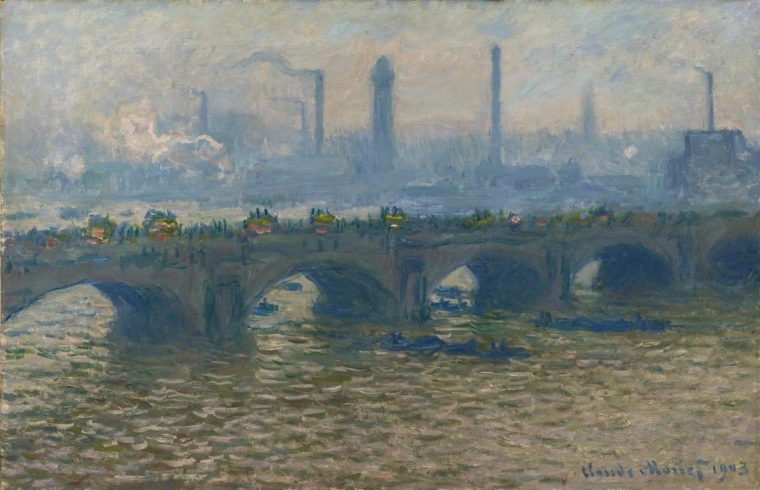

1. Monet and London. Views of the Thames, Courtauld Gallery, London

It’s not unreasonable to say this show is a one-off: after all, it’s taken 120 years to arrange what Monet himself could not: his paintings sold so well at his 1904 Paris exhibition that he was not able to assemble them for a London show. Recreating the sensational Paris exhibition, 21 paintings of the Thames have been reunited at the Courtauld Gallery, minutes away from the Savoy Hotel, where Monet stayed on three occasions between 1899 and 1901, and had a studio. They may feel familiar, but seeing them in person is a revelation – being surrounded by these paintings, in this intimate gallery, is a genuinely immersive experience, in which the shifts of colour and tone, the texture and pace of the brushwork, the fascination with smog, reveal something new about the ambition and tenacious spirit of this visionary artist.

To 19 January 2025 (courtauld.ac.uk/whats-on/exh-monet-and-london-views-of-the-thames)