The morning ahead of my visit to the David Hockney show at the National Portrait Gallery, I was preparing questions for a talk with a young painter. Hockney references washed over the younger painter’s work. In particular the curving patterns with which Hockney described the surface of sparkling water in his Californian swimming pool paintings of the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

There is no question that Hockney is still relevant, that he is a point of reference for younger generations. I grew up seeing his illustrations and his paintings widely reproduced. He has had a formative impact. So why was I filled with lowering dread?

David Hockney: Drawing from Life is a retrospective focusing on the artist’s portraiture, and his drawing practice in particular. The heart of the show is lovely, structured around four important relationships – with his mother Laura Hockney, the designer Celia Birtwell, his lover (later friend) Gregory Evans, and the printmaker Maurice Payne.

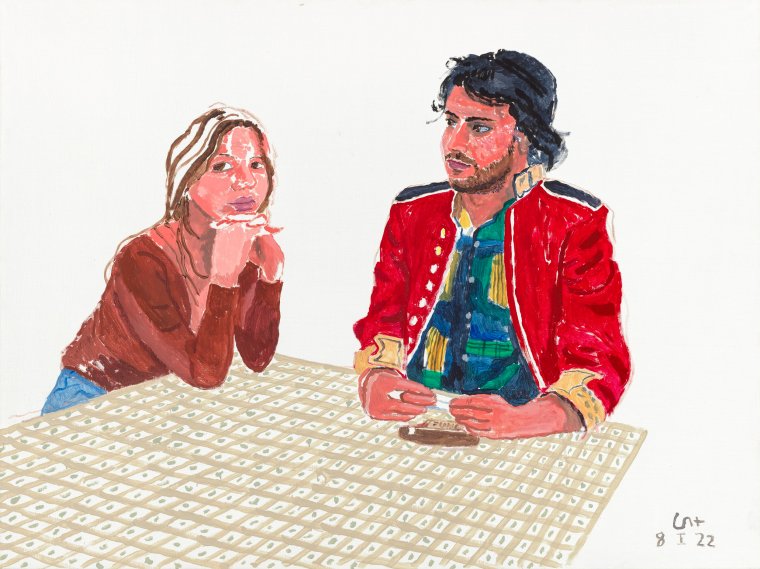

It was what came after this that worried me – a series of painted portraits made in the artist’s Normandy studio in 2021-22. I really did not enjoy Hockney’s iPad paintings made in the same period, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 2021 as The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020. In that instance I could at least admire his career-long commitment to experimenting with new (and old) technologies, from Polaroids to the camera lucida.

This show was to be a return to painting, though, and from the advance images circulated by the gallery, it didn’t look glorious.

Back in August, the National Portrait Gallery teased a Hockney portrait of musician/universal lust object Harry Styles – presumably hoping it would attract a young audience to the exhibition. On screen, at least, it recalled the wilfully naive paintings made by comedian Joe Lycett. So much so that Lycett affectionately lampooned the work, releasing his own “portrait” of Styles on Instagram, together with a suitably ludicrous backstory. (Styles subsequently offered to purchase Lycett’s portrait for £6.)

Hockney is now 86 and not in fantastic health. He still apprehends the world through drawing, almost compulsively. A short film at the start of the exhibition shows him leafing through what look like custom sketchbooks showing meals and streetscapes and town squares and ashtrays. The new portrait paintings are positioned as the exhibition finale. He looks like he’s having a lot of fun with them, portraying himself, brush in hand, all smiles, like a jolly uncle.

He surrounds himself with a broad and evidently fond circle of friends and visitors. Is this his best work? No. While the bodies are often rendered with confident fluency, he seems to become tentative when he reaches the face, as though second guessing himself. There is something hesitant about the actual portraits that stops them hanging together.

Mercifully, the portrait of Harry Styles is very much not the highlight of this exhibition. Indeed, the final chamber of recent paintings feels like a peculiar addendum to what is otherwise a show of thoughtful delicacy, exploring shifts and developments in Hockney’s style through his portraits of those closest to him.

The Celia Birtwell room opens with a sparing ink drawing from the late 1960s in which her face is framed by curls and her eyes by heavy rims of kohl. Hockney is fascinated by the shifting subtleties of her face, apparently seeing her afresh at each sitting. Her extravagant costumes invite colour, and the artist turns to crayons to capture the full glory of her romantic ensembles in Celia Wearing Checked Sleeves (1973) and Celia in a Negligee. Paris Nov 1973.

Within the intimacy of these works is also acknowledgement of Birtwell as a sensuous being. Hockney draws her asleep, or reclining on a bed in a black lace slip. Her sexuality becomes an evident and mysterious source of fascination. One of the central “arguments” of this show is that Hockney sees more in faces he knows well – those he has studied over time always yield new material, while new faces tend to produce less interesting work. Revisiting Birtwell over the decades, Hockney has also experimented with bold, large-format printmaking, bringing her into view with a great variety of different marks and materials.

In one of two photo-collages in the show, we find Birtwell with her two sons and two cats (one the famous Percy, immortalised in Hockney’s beloved double portrait Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy.) The composite photographic image suggests a rush of movement, and time passing – in striking contrast to Hockney’s drawings, which are muffled in stillness, all time arrested.

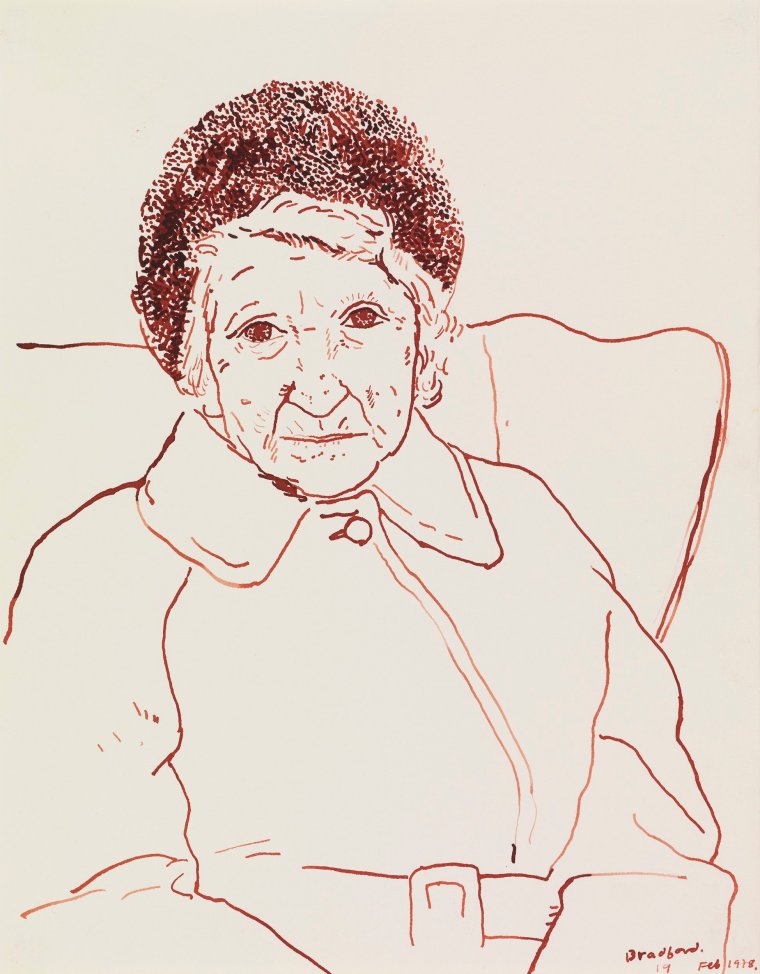

The other photo collage, in an adjacent gallery, is a wonderful portrait of Hockney’s mother Laura, engulfed in a green raincoat, sitting in the funereal ruins of Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire in 1982.

Hockney’s brogues are just visible in the foreground – behold a widowed mother and adult son on a damp day out, surrounded by the architecture of death and commemoration. Beside it is a little ink drawing from three years earlier, of Laura Hockney on the day of her husband’s funeral. Made in sepia ink, a favoured medium of Hockney’s great hero Rembrandt, the gentle portrait again makes a case for the intimacy of drawing in relation to photography. There is no apparatus shoved between the artist and his mother – he is, as he would say, “eyeballing” her.

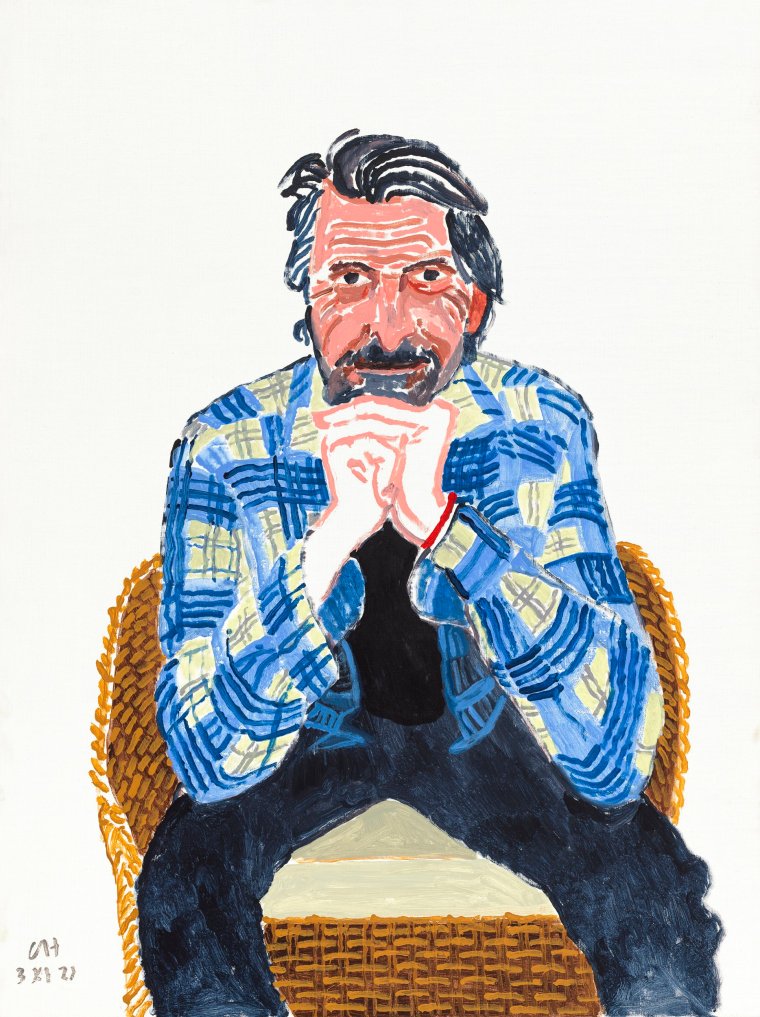

Not that Hockney has a great aversion to technical apparatus. In the late 1990s he made a series of portrait drawings using a camera lucida – a mounted prism that cast a small likeness of the sitter on the artist’s page. Hockney was interested in technologies that may have been used by earlier artists (in this case, the 19th-century French painter Ingres). Rather than tracing a full portrait, the camera lucida allowed him to mark out the position of facial features. He made a number of such drawings of Gregory Evans, which are certainly lively and even a little uncanny, but also far less tender and bewitching than his earlier unmediated drawings.

As Hockney’s lover, Evans’ arrival on the page is intoxicating. Hockney draws him with a fine ink line looking moody and romantic in a trench coat among Roman ruins. In a lithograph of 1976, he is naked but for his gym socks – his calves monumental in the foreground. (Socks are suggestive. Patrick Procktor drew Joe Orton reclining nude but for his socks in 1967.)

Again demonstrating Hockney’s ability to constantly see the same sitter in fresh ways, a standing nude of Evans from 1976 shows him boyish and almost androgynous. A more formal seated portrait finds him camp and dandyish is a giant floppy bow, high-waisted flares and high-heeled boots. Forget Harry Styles – Evans is this show’s grand object of desire.

The Evans gallery shows the greatest swoops of change, in both Hockney’s style and in the relationship between the two sitters over five decades. It is magnificent – a tribute to human changeability, its complex variation posing a ripe antidote to the idea that a human might possess a lone, iconic kind of likeness. We are a thing in motion, in constant change.

The next day, in my talk with the young painter, I asked what he thought I should write about Hockney. He shrugged. “That’s easy – he’s a genius, isn’t he?” Well, quite.

Maurice Saatchi: I used to adore capitalism – then I had lunch with Margaret Thatcher