Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican Art Gallery, London, ★★★★★

“What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!”

Wise, knowledgeable, strong, fearless, good and just: the vision of masculinity inherited from European chivalry is so elevated that it floats forever out of reach. Yet that mythic ideal has endured, finding its 20th-century expression in the cowboy, the soldier and the sportsman.

The Barbican’s fascinating, shocking and seductive Masculinities: Liberation through Photography investigates what has happened to these received ideals of masculinity amid the social transformations of the last half-century. The civil rights movement, feminism, anti-authoritarian countercultures, the de-criminalisation of homosexuality: all have shaken (if not shifted) the dominance of a certain kind of male power.

Over the same period, affordable cameras and mass media have allowed alternative images and ideas of masculinity to circulate. Many of the artists in this show have turned to photography to portray phenomena not represented elsewhere: an affectionate, caring relationship between a son and ageing father; women performing masculinity; the quotidian domestic love of mixed race gay couples.

The exhibition is full of humour, love, and curiosity: rather than attacking ideals of masculinity, it complicates them. An opening section on combat includes Adi Nes’s staged portraits of young soldiers in moments of gentle camaraderie. Opposite are Thomas Dworzak’s found studio portraits of Taliban fighters posed hand in hand in heavy kohl makeup surrounded by artificial flowers.

Rineke Dijkstra’s remarkable portraits of young matadors fresh from the bullring show them blood-splattered and grey skinned, with gashes rent in their brocade jackets. They recall nothing so strongly as the same artist’s portraits of women after giving birth, equally shell-shocked, bloody and glassy pale.

In the midst of the soldiers, cowboys and bullfighters are two little films presenting loss of control. Knut Åsdam’s Untitled: Pissing (1995) shows a man’s trousered crotch as it floods from within. In Bas Jan Ader’s I’m Too Sad To Tell You (1971) the artist appears emotional and weeping in front of the camera. Boys don’t cry, and they are certainly not allowed to wet their pants: in performing these intimate, taboo actions for public consumption these men become a spectacle and invite our disapproval (Naughty Knut! Naughty Bas Jan!)

Where are the daddy figures to tell them off? Around the corner, Karen Knorr and Richard Avedon portray the establishment on either side of the Atlantic. Shot during the run up to the 1976 presidential election, Avedon’s portrait series The Family presents the nexus of power: Henry Kissinger, George H.W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, union leaders, military personnel and senior members of the legislature. They are, it perhaps goes without saying, mostly male, mostly white.

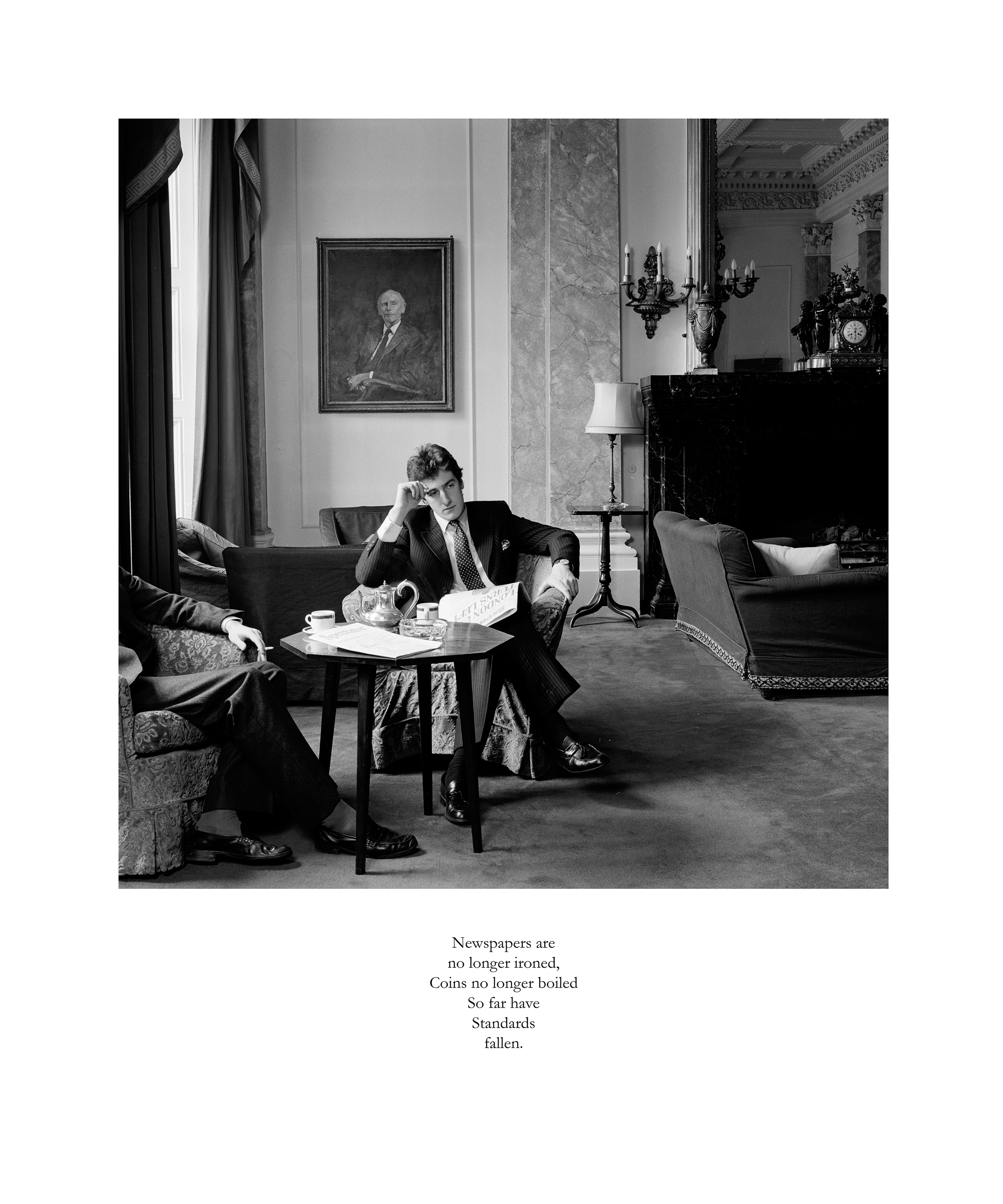

Knorr’s razor-sharp Gentlemen (1981-3) occupies the male universe of the private members clubs of St James’, London. Impeccably suited and regal in bearing, her gentlemen exude the entitlement of power inherited. Knorr places each portrait above a short quote on the English Gentleman and his refined milieu: one in which newspapers are ironed, coins boiled, and standards of dress and decorum maintained even in the most trying circumstances.

Plastered across the wall opposite, Piotr Uklański’s collection of film stars, from Marlon Brando to Rutger Hauer, costumed for an apparently never-ending supply of roles as Nazis suggest an ongoing fetish for handsome uniformed authority figures.

Fathers loom large. Wrestler Adrian Street credits his desire to spite his father with his drive to succeed. Jeremy Deller’s irresistible video portrait of Street, So Many Ways To Hurt You (2010), broadcasts before a psychedelic mural presenting his “exotic” transvestite stage persona against the distant view of a colliery. Deller tracked down Street after finding a photograph of him in full glam regalia, a champion’s belt around his waist, posed opposite his aghast miner father at the pit head.

Richard Billingham’s series documenting his parents Liz and Ray (published as Ray’s A Laugh in 1996) shows his alcoholic father woozy, crestfallen, weak, jubilant, chortling, drinking, embracing. Billingham casts a critical eye on his difficult, struggling parents, but the picture he offers of Ray – the antithesis, in many ways, of the noble masculine ideal – is also affectionate.

Topping the list of works you probably couldn’t make today is Hans Eijkelboom’s With My Family (1973.) The artist approached women at home with their kids during the day, and asked to pose with them for a family portrait. He appears on three sofas, posed plausibly and near-identically with three different more or less entertained or awkward children on his lap and three different women beside him. Thus, apparently, do we construct our interchangeable vision of the nuclear family.

Richard Mosse and Andrew Moisey explore the dark flipside of power and entitlement as manifested in US college fraternities: a system that rewards tribal behaviours, bullying, intoxication, and predatory sexuality. Watching Mosse’s Yale frat boys screaming themselves hoarse for his camera, it’s hard not to imagine these same young men a few years later, leading banks, corporations, and political parties, having absorbed the lesson that he who shouts loudest wins.

Queer masculinity is addressed in the most photographically lush section of the show: much unabashedly admiring. Peter Hujar and Sunil Gupta both capture the masculine beauty abounding on New York’s Christopher Street in the 1970s. Shot in the same era, George Dureau’s portraits of broad-shouldered, glossy-locked double amputee B.J. Robinson confront the question of who is and isn’t allowed to participate in the framework of desire. Isaac Julian’s celebrated film Looking for Langston (1989) is shown in full: a caressingly shot and intoxicating celebration of queer black love.

The reductive clichés imposed on black men are flagged up in Hank Willis Thomas’s Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008 – a collection of advertising images, text and branding removed, showing an endless repetition of archetypes, from clown to sportsman to gangster.

The show performs a neat flip at the end in a section exploring the female gaze: women turning their cameras on men. For some, there’s a sense of justice. Laurie Anderson’s Fully Automated Nikon (1973) uses the camera as retaliatory weapon, capturing a portrait every time the artist is catcalled on the street. In 1977 Marianne Wex examined the way men’s body language expressed a sense of ownership – both over the public space occupied by wide-spread knees and the women’s bodies they felt entitled to touch.

Other artists adopt covert strategies of fetishistic observation – Annette Messager photographs the crotches of men walking past; Tracey Moffatt films young surfers struggling to remove their wetsuits in a car park – they feel grossly intrusive, no less so for being shot by women. Both raise pointed questions about how habituated we are to women’s bodies constantly being submitted to a critical, sexualising gaze, and how often, too, they are portrayed reduced to a few erotic signifiers.

Alongside Dijkstra, Knorr, Hujar, Julien and Gupta are too many outstanding artists to list, including star turns by Catherine Opie, Rotimi Fani Kayode, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Mikhael Subotzky. The Barbican has had a winning streak in the last few years, with prescient themed exhibitions that lay the ground for complex, timely debate. Previous exhibitions felt overwhelmed by the weight of ideas: too much text, not enough art. Not so in Masculinities: this is likely to be one of the defining shows of the year.

‘Masculinities: Liberation through Photography’ is at Barbican Art Gallery, London, to 17 May