Pop the Champagne! Hang out the bunting! After a three-year closure and a £41.3m top-to-toe refurbishment, the National Portrait Gallery opens its doors again tomorrow. And what doors they are: Tracey Emin’s portraits of women, who could be you, me, Cleopatra, your mother, cover three sets of monumental bronze panels, setting the tone of the Gallery’s transformation from a dusty male mausoleum to a lively family album for the nation.

The gallery’s reorientation is not just conceptual: the main entrance has moved round the corner onto Ross Place, effecting a welcome upgrade of the West End’s biggest urinal into a pedestrian-friendly oasis of calm. Seating, trees, and a view of the previously rather anonymous statue of Victorian actor Sir Henry Irving makes this new north-facing piazza the more elegant little sister of Trafalgar Square.

Once inside, and past the inevitable huge shop and a welcoming committee of sculpted portrait busts, among them Nelson Mandela, Thomas J Price’s imaginary portrait of a young black woman, and Jacon Epstein’s self-portrait, visitors will only need a moment to get their bearings – the new ticket hall is the old one, turned the other way round.

Director Nicholas Cullinan said that the redevelopment, which was funded by private donations, and grants from the Blavatnik Family Foundation and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, “represents the most significant transformation in our history since our building opened in 1896.” A new accessible entrance, larger public spaces, increased wall space, and improved lifts fulfil what architect Jamie Fobert, who has previously worked on similar projects at Tate Modern and the V&A, described as the desire for the Gallery “to open up to the public in a way the original building did not”. But he also emphasised the involvement of heritage architects Purcell, who have been instrumental in retaining the historic character of the Victorian building, and revealing “the great historic building Londoners never knew they had”.

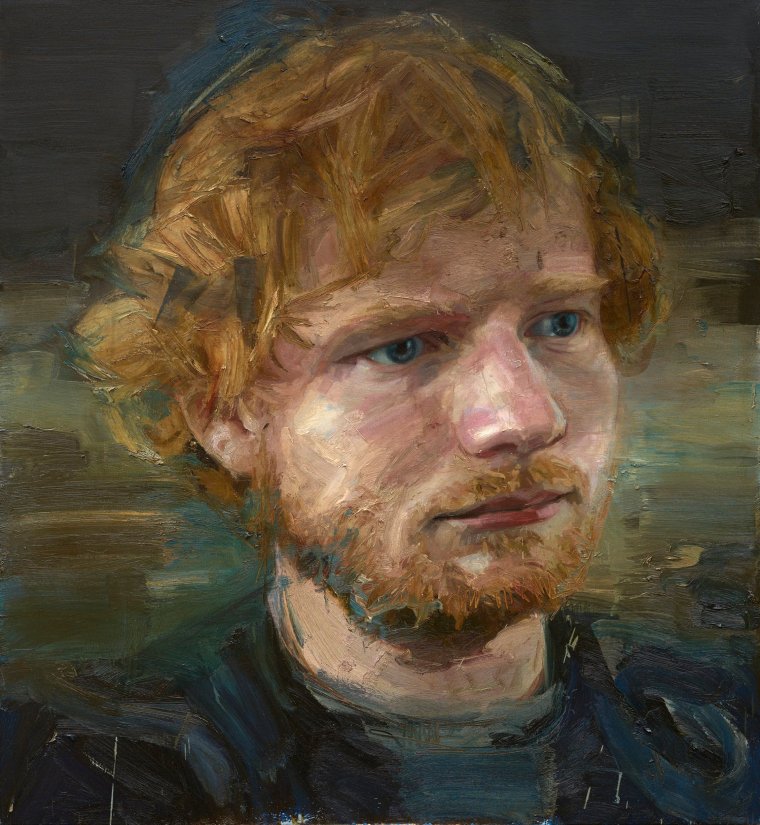

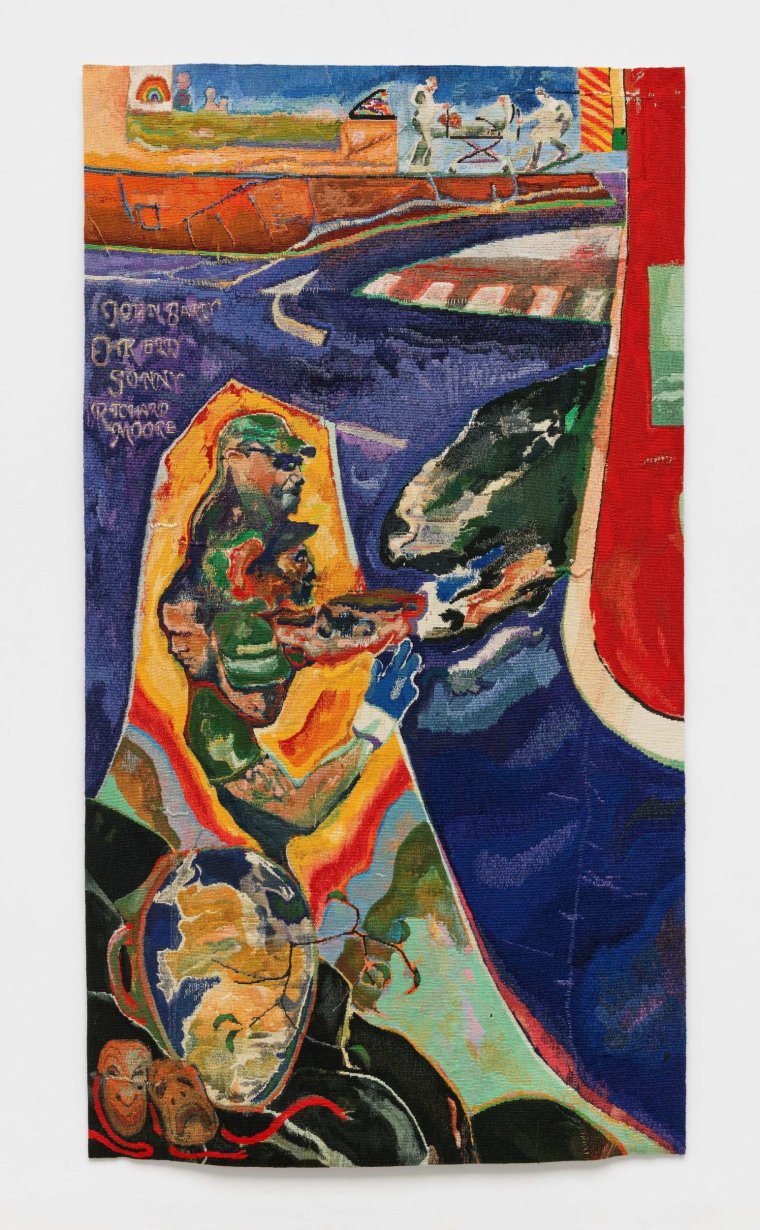

Now much smaller, but typifying the new focus on extending a welcome to all, the ground floor exhibition space will host a regularly changing display of contemporary figures and new acquisitions. For now, a tapestry by Kenyan-British artist Michael Armitage, of four refuse collectors during the lockdown, is joined by contemporary worthies including Ed Sheeran, Baroness Lawrence, and a rather lovely new painting of Jeanette Winterson in her vegetable garden.

As before, it’s up the escalator to the start of the permanent displays, where the Victorian bones of the building, with its parquet floors and wood panelling, are set off with adventurous new wall colours, inspired by nearby paintings. In the Tudor galleries, which mark the beginning of a walk through 500 years or so of British history, the deep blue background of Katherine Parr’s full-length portrait suggested the wall colour.

In a gallery dominated by the extraordinary number and variety of portraits of Elizabeth I, the reference to Katherine Parr feels like a forceful statement of intent, emphasising the new prominence of women across the entire rehang, which has increased in the 20th and 21st century galleries from 35 per cent to 48 per cent.

People from minority ethnic communities are also better represented than before, and feature in 11 per cent of works on display, against a previous figure of 3 per cent. Partly, this has been achieved by the freeing up of office space to create the Weston Wing, which has allowed the number of works on show to increase from 876 to more than 1,100. But centuries of prejudice are not easily overcome, and in order to present the untold stories of historically marginalised groups, the curators have had to look beyond the standard fare of large-scale oil paintings celebrating eminent white men.

Thousands will thank them for this: gone are the boring ranks of identikit men in black, replaced by a fascinating mixture of paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and photography, which not only give a sense of the vibrant and diverse people who have contributed to British history and culture, but simply makes a more visually exciting experience.

One of the most enjoyable new exhibits is a wonderful folding screen, made for Lord Byron by his fencing teacher Henry Angelo. Decorated with an array of printed images of boxers and actors, it’s a Who’s Who of the seedier side of London life around the turn of the 19th century, and a remarkable testimony to the popularity and availability of printed images at that time. The screen serves as the centrepiece for an informative, and not overly wordy thematic display on printmaking techniques, which leads into a section on slavery and the abolitionist movement.

Inevitably, there aren’t many portraits of black campaigners, and those that do exist are more likely to be lowly prints made for distribution in pamphlets than more prestigious paintings. Undeterred, the curators have chosen to counter the stiff portraits of white merchants and abolitionists, with the help of a small screen presentation, which brings together printed material from collections across the country to relate stories of experience and resistance to slavery and the campaign for abolition.

In fact, though usually modest in scale, there are more 18th and 19th century portraits of black people than might be imagined, and the most remarkable of them all is Sir Joshua Reynolds’s acclaimed masterpiece, the Portrait of Mai (Omai), c. 1776, which director Nicholas Cullinan called “by far the most significant acquisition the National Portrait Gallery has ever made”. Mai came to Britain from Polynesia with Captain James Cook, and remained in London between 1774 and 1776, where he became a celebrity, returning to the island of Raiatea in 1777. Reynolds’s painting was saved for the nation thanks to a historic joint fundraising campaign by the National Portrait Gallery and Getty, and will tour the UK and US following its initial appearance in London.

For now, it is the jewel in the most spectacular gallery in the building, which has been beautifully hung from floor to ceiling with paintings of actors, musicians, boxers and painters, emulating the Royal Academy exhibitions that, as Bridgerton fans will know, were a favourite society event from the mid-18th century.

Downstairs, the spaces are more intimate, and the thematic displays more extensive, and featuring a variety of material that makes each room a treasure house of stories, names and faces. There’s a space dedicated to the Lucian Freud Archive, a tribute to one of Britain’s greatest painters of portraits. And a room surveying 1914-1930 basks in the creative vibrancy of that era, the angular sculptures of the composer William Walton and writer Edith Sitwell contrasting with a soft, melancholy watercolour of the poet Charlotte Mew, and a similarly ethereal photograph of the avant-garde dancer Margaret Morris.

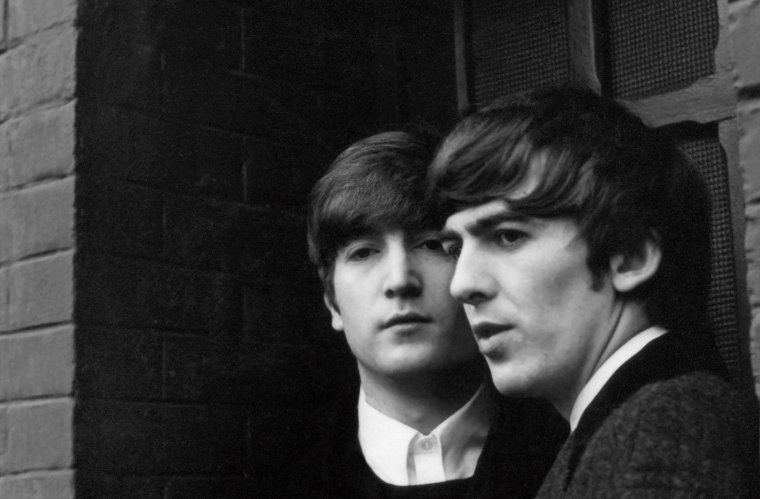

Photographs now make up 29 per cent of works on show, compared to just 4 per cent previously, and the NPG’s reputation for staging spectacular photography exhibitions is due to be carried forward in forthcoming shows on Paul McCartney, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron.

New research and discoveries are also a speciality that the NPG is rightly proud of, and the opening exhibition on a pioneer of colour photography, Yevonde, plays to all of these strengths, in the most festive way imaginable. Yevonde was a one-off, a brilliant maverick who set up her London studio just before the outbreak of World War One, and whose portraits and commercial work were staples of fashion and society magazines. More than 25 newly discovered photographs are included in this exhibition, which celebrates Yevonde as a pioneer of women’s liberation, for whom photography was a ticket to freedom.

For all that, perhaps the most welcome aspect of the show is that in the context of the NPG’s new, more egalitarian hang, Yevonde’s gender is the least remarkable thing about her. Instead she is one part of a richer, more detailed panorama of her time.