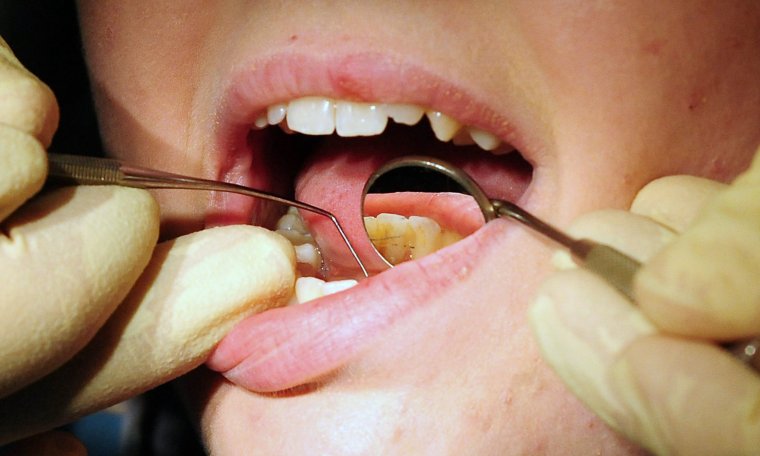

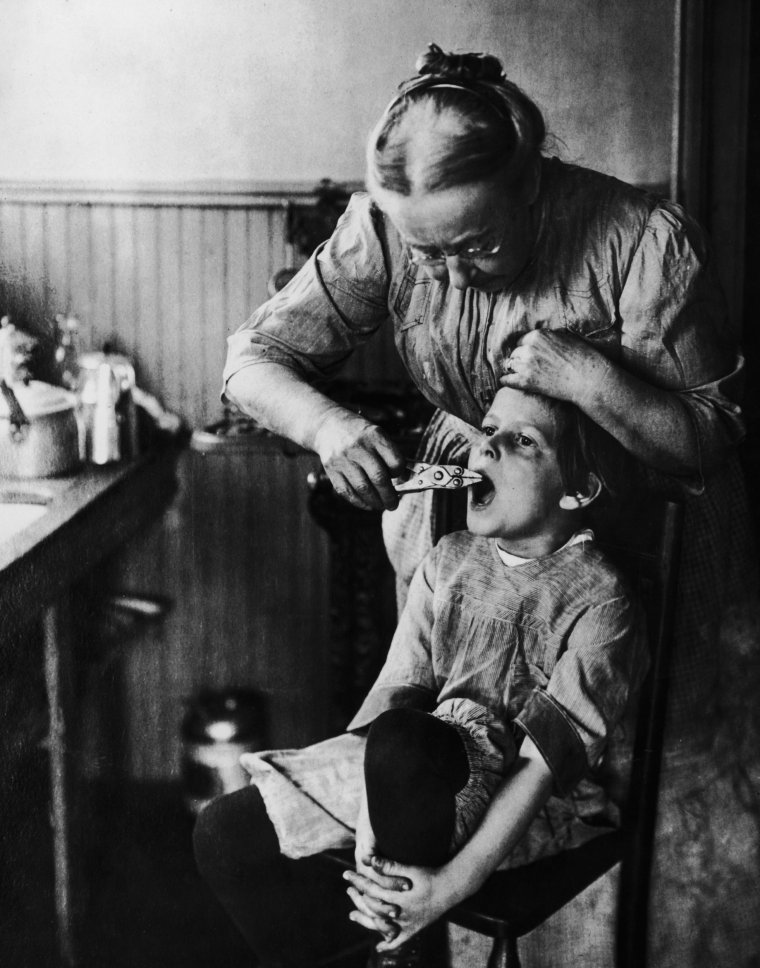

When yet another person walks into Beth’s NHS urgent dental service after trying to remove their own teeth with pliers, she despairs. Not at the patients and what they’ve done to themselves, but at their agony caused by the shortage of NHS dentists.

“That shouldn’t be happening; it’s awful,” says Beth, who has dealt with multiple “DIY” cases. “I can’t imagine how desperate people must be to do that, without anesthetic, when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“During the pandemic, we saw the disasters that happen when people try DIY haircuts, but doing it with medical procedures is absolutely wild. In what other area of healthcare would people feel they have to attempt their own treatments? The situation is unacceptable.”

Beth, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, works in NHS urgent care three days a week and at a private practice on the other two. Many of her shifts are spent performing emergency care to patients in evening clinics or at weekends.

She often treats people – including children – who have barely any teeth left or need multiple extractions after being unable to see a general dentist. Based in the south-west of England, her area is a “dental desert”, where people can wait for years to enrol with an NHS practitioner.

Nearly six million fewer courses of NHS dental treatment were provided in England in 2022/23, compared to the 38 million in the year before the pandemic. Scotland also has a problem, with people said to be travelling to Turkey and even as far as India for treatment.

Across the UK, 22 per cent of people are not registered with a dentist, according to a YouGov poll last year. The health and social care select committee says this is “totally unacceptable”, but the problem is even worse in Beth’s county. “More than half the population are unregistered here,” she says.

For some people, the results aren’t just painful, they’re fatal. The British Dental Association (BDA) fears that a decline in the availability of NHS dental services will “cost lives” to mouth cancer.

The number of people who died from the disease in the UK in 2021 was up by 46 per cent from a decade earlier, according to figures obtained by the Oral Health Foundation.

Around nine out of 10 sufferers survive at least five years when the disease is diagnosed early, but that typically requires regular dental check-ups. When it is spotted later, that survival rate drops to 50:50.

“When I was in dental school,” says Beth, “I got the impression that I might see a couple of cases of oral cancer in my whole career. I’ve only been qualified for a few years, but already I’ve made six referrals that have resulted in cancer diagnoses.”

She feels it is her duty to speak out about how so many unregistered patients in the UK are suffering and why she believes there is little sign of things improving, despite Government pledges.

“What’s happening is shocking,” she says. “It’s awful and people need to know.”

Over the course of three days at work, she spoke to i about the appalling cases she encountered in her shifts, being careful to anonymise all her patients.

*****

Three days of pain

Saturday: Children with ruined mouths

Today I was working in urgent out-of-hours care. Seeing emergency patients who don’t have a dentist gives me an insight into how the system is failing.

These services are purely for people with severe problems that need immediate attention; things such as traumatic injuries, facial swellings or complications after surgery. We’re often double booked and have to stay late.

The phones opened at 8.30am and our appointments were full within an hour. If more people call in, we sometimes send them to A&E.

I saw about 20 patients during the day. Two of them were children with severe facial swellings. One little boy was six years old and it was his first time seeing a dentist. He needed a tooth taken out. It’s hard enough for any child to be cooperative enough for us to do this, but it’s especially difficult when they’re so worried and unwell.

We gave him an urgent referral to paediatrics at a community service, for the tooth to come out under general anaesthetic. But the waiting list is ridiculous. There are so many children on it, so before then we might see him as an emergency case again. And he might have other problems in the meantime – he had decay in almost every tooth.

A few weekends ago, I saw a child who had just turned three. He had a case of “bottle caries”, where they’d been sleeping with a bottle in their mouth. This bathes teeth in milk and they can rot very quickly. This boy needed almost all of his teeth taking out under general anesthetic, leaving maybe four behind. His adult teeth won’t start to come through until he’s about seven, so he’ll start school with barely any teeth. That could affect his speech, his friendships – it’s a big deal. It sounds shocking, but you’d be surprised just how common it is.

This is why we recommend a dental check-up for children before the age of one. Labour has suggested introducing supervised toothbrushing in schools if it wins the general election. I’d support anything that encourages children to brush their teeth more, because unfortunately there are neglectful parents out there – but often it’s too late by the time they’re in school. So would this have the desired effect? Probably not. And is it really the responsibility of teachers?

The NHS dental crisis

- NHS-funded dental services in England are in “widespread crisis” and “near-terminal decline”, according to the Nuffield Trust healthcare think-tank.

- In 2022, nine in every 10 NHS dental practices across the UK were not accepting new adult patients, a BBC investigation found.

- Even when NHS treatment is accessible, 61 per cent of people still find the treatments expensive, discouraging many from going to check-ups, according to one survey by Healthwatch.

With facial swellings, often there’s an infection and an abscess around the tooth. Sometimes the swelling is so severe the patient can barely open their mouth more than a finger’s width. That stops us getting to the problem. It’s a medical emergency too, because they can’t eat and could choke if they vomit.

I had a patient in his 30s with this problem. He had already received two different antibiotics and his mouth opening hadn’t improved. We’re supposed to avoid using antibiotics too much because of the increase in resistance, but if everyone had access to NHS dentists and abscesses were being prevented through check-ups, we wouldn’t need to prescribe them so often.

This guy was unregistered and hadn’t seen a dentist in about a decade. He needs a full clearance – all his teeth being removed and a denture being fitted to replace them. We can refer him to a community service for the extractions, but getting a denture will be difficult.

Right now, however, he needed to have his jaw prised open and the infected tooth taken out. We couldn’t find anyone to see him, so we sent him to A&E. I called the hospital to let them know he was coming, but he still had to wait because they were so busy. His frustrations boiled over and he abused some of the staff, so they refused to treat him. All I could do was prescribe more antibiotics and some very strong pain relief and he’ll have to wait until the consultant is willing to see him again.

Monday: Letting down the most vulnerable

Today I saw another 20 unregistered patients. One of them came into our emergency dental centre two years ago with severe toothache. He needed root canal treatment back then to save one of his teeth, but we could only do the first stage. He needed a general dentist to complete the job.

For that, of course, people need to find a dentist they can register with. Good luck.

Quite often people come back to us having been unable to find anyone on the NHS, by which time their tooth has worsened and needs to come out. That’s what had happened with this man. He’s in a good job and understands oral hygiene, he isn’t vulnerable and hasn’t done anything wrong, but now he has an abscess. He was saying: ‘I’ll get it done privately,’ but he’ll need to find the money.

Later, I saw an elderly gentleman for another extraction. We see him in emergency care every couple of years; he’ll have a tooth out and go off again. He’s down to only a few teeth now, but we have no provision to give him dentures. That massively impacts his life, including his nutrition. We’ve relieved his pain for now, but his underlying problems aren’t being resolved.

The other day in the emergency clinic, I took out 18 teeth. That’s pretty standard. In the past couple of years, I must have done thousands of extractions. It’s sad because almost every one is preventable.

I also saw a homeless man in his 30s. Every one of his teeth has rotted right down to the stump, so he’s living in constant pain. It’s from a history of drug abuse and being put onto methadone, which is terrible for teeth. He’s been suffering for years, unable to eat normal meals. Today he had eight extractions and it was the next stage of making his denture.

A ‘special-care patient’ was brought in by his parents. We have to make referrals for people with severe physical or cognitive disabilities, who might be non-verbal and live in supported accommodation. He can’t tell anyone if he’s in pain, but his parents noticed the signs. He needs a general anesthetic, but the waiting lists are so atrocious. It’s our most vulnerable people in society who suffer.

The queue that said it all

- The NHS dental crisis shot into the national consciousness again last month when hundreds of people began queuing down a street in Bristol in the hope of registering with a newly-opened practice.

- Police had to manage the line, which reportedly included a disabled cancer sufferer, who could barely stand.

- Their wait continued the following day, apparently leading to a fight over someone jumping the queue, and even lasted into a third day before all places at St Pauls Dental Practice were filled.

- Among those in the queue was 66-year-old teacher Norman Stephenson, who revealed he had tried using superglue to repair his dentures.

Tuesday: Cancer concerns

A patient who hasn’t had a dentist for about a decade came in for an emergency appointment recently. She had some loose teeth, and when I lifted up her lip, she also had a suspicious lesion that I worried could be more serious. I asked her: ‘Have you not noticed the huge ulcer?’ She had no idea it was there. We made an urgent referral for her to be tested by a specialist within two weeks, and now her results have come back.

I was right: it’s oral cancer.

It was really sad hearing that news.

It’s one of the least treatable cancers unless it’s caught really early. But it’s also asymptomatic until it reaches a bad level – so unless you’re lucky, you need to be seeing a dentist regularly for it to be spotted in time. This is totally overlooked by politicians.

Most people don’t often look at the back of their throats, underneath their tongue, right up under their lips. We encourage the public to do this, in the same way that they’re meant to check their breasts or testicles, but our mouths can look quite odd to people who aren’t experts.

This woman was diagnosed at a late stage, so she’s definitely in danger. She’s in her 60s, but it can affect people of any age. She had been on the NHS waiting list for years and only had about six teeth remaining, with no dentures to replace the missing ones, so she was already struggling with nutrition.

Seeing a dentist is not just about improving our health, it’s potentially life-saving. I know of one person who was diagnosed with a form of mouth cancer after it was picked up early during a routine appointment. They had an operation and they survived.

They could afford to be seen regularly as a private patient. Imagine if they weren’t so fortunate and couldn’t get an NHS appointment: they could be dead.

It was quite a difficult day all round. Another patient I saw was a man in his 20s with severe toothache, who had rung for an ambulance the day before, only to be turned away from A&E because they won’t deal with toothache. But he was crying when he came in – he said he’d even thought about suicide because of the sheer pain. Toothache can be one of the worst things we experience. We did an emergency extraction, but he still went away with other problems that ought to be treated.

*****

DIY dentistry

- A poll of 500 dentists last month found that 82 per cent had seen patients who have “taken matters into their own hands since lockdown”, according to the BDA.

- The TV presenter Paddy McGuinness told Question Time last month that his father “took his own teeth out because he couldn’t get a dentist appointment”.

- The 87-year-old mother of Labour MP Grahame Morris tried her luck with pliers. “My mother is 87 and very frail,” he told Parliament in January. “She did this out of desperation. It is appalling.”

- Caroline Pursey, 63, from Lincolnshire, told i last month that she pulled out four of her teeth after her NHS dentist went private. Her nearest alternative was 50 miles away with a three-year waiting list. “It was painful and they were growing on each other, so I couldn’t eat at all,” she explained.

- Chris Langston, 50, from Shropshire, pulled out a tooth because having it done privately would cost £90 and involve a 60-mile round trip. “I wouldn’t recommend it. Not to anyone. It was horrible,” he said.

Grave doubts over the ‘dental recovery plan’

Given that many of the problems Beth sees are down to people being unable to access dental services, she says: “I would love to work in NHS general practice full-time.” But financially this “wouldn’t be viable”, she laments.

Working in urgent care three days a week, Beth is in a salaried role – receiving around £35,000 a year from the NHS, which she is happy with. But most general practice dentists offering pre-booked appointments to NHS patients in England are self-employed, working under a contract that many feel is neither fair nor financially sustainable. This, they claim, is the main reason for worsening availability.

The contract, introduced in 2006, means they are paid per completed course of treatment. This is banded but makes little allowance for how many procedures a treatment involves, nor how complex or time-consuming they are.

When dentists see neglected mouths needing lots of attention – which is often the case with newly-registered patients – this can leave them out of pocket, says Beth. She has worked under the contract in the past, but would not do so again without radical change.

“The Government has been driving a narrative to make ‘greedy dentists’ look like the villains, saying we’re abandoning the NHS to earn more money,” she argues.

“It’s scary to think this, but you could do a whole day’s work and receive less than the minimum wage, because of the level of need in my county and how the NHS contract works. The system makes it impossible to do that and be able to live comfortably.

“If they need one extraction and a denture, or if they need four root canals, six extractions and dentures, you’re paid the same – and then you have lab fees to pay,” she explains. “You can end up making a loss on some patients.” If all of the patients had severe needs, she would be in trouble.

“I could work five days a week privately – there’s more than enough demand,” she adds. “Or I could work less and spend more time with my family. But I’ve seen how much people really need help. I don’t want to abandon patients with nowhere else to go. I can also see why people move away from the NHS.”

“You could do a whole day’s work and receive less than the minimum wage”

‘Beth’

The prime minister admitted last month that it was “too difficult” to access an NHS dentist. Rishi Sunak recognised that it had been a particular “challenge” in Beth’s region, the south-west of England, but he said he hoped the Government’s £200m dental recovery plan would “fix” the problem.

Up to 240 dentists will be given a £20,000 bonus if they open services in areas with poor NHS availability, and those taking on new patients will receive higher payments. Mobile dental vans will also be introduced for isolated and under-served communities. The Government hopes this “hugely ambitious and far-reaching plan” will lead to 1.5 million more treatments over the next year.

But the BDA says the programme “won’t halt the exodus from the workforce” and fails to offer “real change”. Beth agrees.

“It’s like putting a plaster on a bullet wound,” she says. “The little things they’re bringing in are not going to change the availability of services. They make small tweaks.”

Labour has promised to provide an extra 700,000 urgent dental appointments and reform the NHS dental contract, together with other measures, if it wins the next election. The Nuffield Trust says the proposals “make good sense” but are “unlikely to stem the decline”.

Beth is also angered by the clawback system, with dentists being penalised if they fail to meet strict targets on how many treatments they deliver. “Doctors would never have to pay money back to the NHS for not seeing a certain number of patients – such as when a surgeon sees one patient in a day, but it was a long operation.”

Clawback can also result in “well over 10 per cent of dentistry’s £3bn budget” being lost to other areas of the NHS, according to the BDA. More broadly, the union warns of a “postcode lottery”, with nearly a third of local dental budgets going unspent in some areas of England because struggling practices miss targets.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson told i: “The Government already invests more than £3bn each year to support NHS dentistry and we are starting to see progress. Last year, 1.7 million more adults and around 800,000 more children saw an NHS dentist compared to the previous year.

“Our new dental recovery plan, backed by £200m, will create an additional 2.5 million appointments over the next 12 months, including by offering cash incentives to practices to take on new NHS patients.

“We are also strengthening the workforce through the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, which will expand dental undergraduate training places by 40 per cent per year by 2031 to 2032, with an initial 24 per cent increase by 2028 to 2029.”

However, Beth maintains that “propaganda” about the recovery plan is “misleading” for those who have read the news and excitedly ask her if they will soon be able to register with a dentist.

“It must be terrifying to live in a dental desert, like in my county,” she says. “There are literally no NHS practices here taking on new patients. When some children are born, their parents are told they’re going on a 10-year waiting list. In that time, they could have problems that affect their whole lives.

“The system is spectacularly failing a lot of people.”

Maurice Saatchi: I used to adore capitalism – then I had lunch with Margaret Thatcher