Whatever else Liz Truss does after being applauded into No 10 as the UK’s new prime minister, she will have already broken one age-old convention. Her appointment in Balmoral on Tuesday rather than at Buckingham Palace, because of concerns about the Queen’s mobility, means her time in office will begin differently to every other leader since Herbert Asquith, who took the reins in 1908 at the French resort of Biarritz where King Edward VII was on holiday.

Apart from the unusual location and means of transport back to Downing Street, however, the rapid mechanisms of her assuming power and forming a government will follow the same intense and fascinating process as ever.

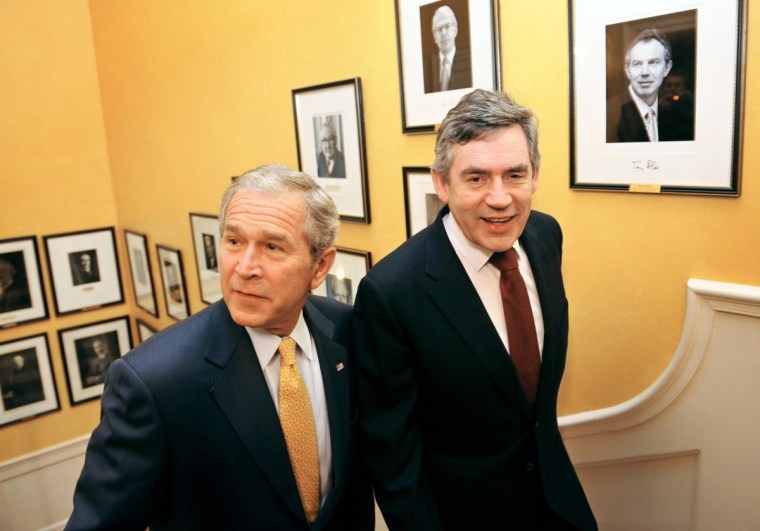

There are also lessons from her predecessors to heed or ignore, which Truss may want to brush up on after beating Rishi Sunak in the Conservative leadership contest on Monday by 81,326 party members’ votes to 60,399. Perhaps she will suddenly have to search for glue to seal her nuclear orders as David Cameron did, or sneakily appoint her Cabinet away from the cameras like Gordon Brown.

There are few people more qualified to guide us on what a prime minister faces in their first hours and days in the job than Dr Catherine Haddon. She has studied the UK’s transition of power for 14 years with the Institute for Government and has met prospective PMs in the past to brief them personally on what to expect, taking them through her in-depth guide.

New PMs do not get months to prepare a transition like US presidents, who are elected in November and take office in January. But “there will have been a lot of work behind the scenes” with Truss and Sunak ahead of the Tory leadership announcement, Haddon tells i. “The Cabinet Office will be talking them through this process and discussing their plans for government, the immediate things that they need the Civil Service to be ready for on day one.”

Meeting the Queen

Truss’s flight to Balmoral will be very different to Clement Attlee’s journey for his appointment in 1945. He was driven to Buckingham Palace to meet King George VI by his wife Violet in their family car, a Hillman Minx. Neither of these two shy men knew what to say to each other, but Attlee eventually broke the silence by uttering: “I won the election.” The King, who had accepted Winston Churchill’s resignation with sadness minutes earlier, replied simply: “I know, I heard it on the six o’clock news.”

In some ways, things will be easier this week than a changeover the morning after a General Election. Boris Johnson, his family and his team have known for weeks that they will need to move out and when this will be. It is expected that he will address the nation on Tuesday morning before flying to Scotland and submitting his resignation to the Queen. Truss will be ceremonially appointed minutes later.

“Contrary to myth, the Queen and her Prime Minister do not ‘kiss hands’: they shake hands,” Brown writes in his autobiography, My Life, Our Times. But Tony Blair recalls in his book A Journey being told by a palace official to “brush them [the Queen’s hands] gently with your lips”, which left him “disconcerted”. Going through a door to meet her just seconds later, a nervous Blair found himself “unfortunately tripping a little on a piece of carpet so that I practically fell upon the Queen’s hands, not so much brushing as enveloping them”.

Truss will begin work on her official flight back to London, ahead of a speech scheduled for 4pm. This gives the new leader’s team more time than usual to prepare for their boss stepping through the black front door, but “there will still be a rapid handover in Downing Street, whenever the magic moment happens”, says Haddon.

One might expect the common party of the outgoing and incoming leaders will help. But with the Theresa May to Boris Johnson changeover, following a particularly long and bitter tussle for power, “the special advisers serving the old administration were somewhat persona non grata with the new government”, says Haddon. “It was awkward trying to make sure that they didn’t encounter each other. I don’t think it worked entirely.”

The first speech

Truss will no doubt hope her debut address in the role outside No 10 eclipses the peculiarly animated “cheese speech” she gave to the Conservative party conference in 2014, which is so often used to deride her online.

Prime ministers are now granted more dignified moments for their first speeches at Downing Street than in Margaret Thatcher’s day. In 1979, she faced a gaggle of reporters who gathered by her car and had to be held back by police officers while she answered questions from the BBC. It was here that she quoted St Francis of Assisi: “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. Where there is despair, may we bring hope.” The booing in the background did not bode well.

Gordon Brown was also conscious of protesters. He was “determined to give my remarks without notes or a lectern”, he writes, but worried about fluffing his lines amid the noise of “helicopters above, waiting press and TV cameras, and an expected posse of anti-Iraq War demonstrators only yards away outside the gates at the end of the street”. To prepare for this, he rehearsed with the help of two close allies who “hurled abuse in my direction, trying to distract me and shout me down”.

Inside No 10

After the clapping has stopped inside No 10, a new PM is typically greeted by the Cabinet Secretary, a role held today by Simon Case, and taken into a civil service briefing covering everything from ministerial appointments to intelligence information – but also their choices of office space and living arrangements.

Truss has three options for where to work in Downing Street. “Margaret Thatcher had what was called her study on the first floor, by the stairs that led to her No 10 flat,” writes David Cameron in his memoir, For The Record. “Tony Blair had his ‘den’ at the bottom of the main staircase, whose yellow walls are tiled with pictures of his – our – predecessors. Brown opted for something different – something that resembled a trading floor or newsroom.” Cameron made the same choice as Blair.

The PM can also tailor the timings and structure of their work. Cameron started at 5.45am each day, spending two hours working through the papers his staff decided need his attention and had placed in his red box, and would meet twice daily with his Chancellor George Osborne at 8.30am and 4pm.

The new leader and her family have the choice of living in the smaller flat above No 10 itself or the bigger one above No 11 – though some have been tempted to not move in at all. Cameron’s wife Samanatha “wasn’t sold on the idea of moving into either the flat above No 10 or that in No 11,” he writes. “So that night, my first as PM, I went home to North Kensington.”

Cameron realised the next morning this meant being taken from his terraced house to his place of work in a motorcade every morning. “I felt like President Mugabe,” he writes. It wasn’t until the end of the first month that the couple decided to move to Downing Street and “brought across the entire contents of our home – bikes, beds, beanbags”.

Truss will need to consult her husband, accountant Hugh O’Leary, and their two daughters Liberty and Frances. They will have the option of a freshly decorated flat above No 11, following Johnson’s refurb by celebrity designer Lulu Lytle, which reportedly cost £140,000 and was initially funded by a Tory party donor in a controversial arrangement.

Immediate pressure

There is no time for celebration after a politician achieves a lifetime ambition and becomes PM. John Major writes in his 2010 autobiography that right after walking into No 10 with his wife Norma to applause from his new staff, his Principal Private Secretary “escorted me into the Cabinet room; Norma went upstairs to the flat. There were already decisions waiting which needed approval.”

This is likely to be true for Truss, especially given how Johnson is said to have mentally checked out of his job leading what appears to be a zombie government, having taken two holidays in three weeks over the summer. Growing anger about a perceived lack of government action to tackle the cost-of-living crisis means the new PM may enjoy no real honeymoon period, feeling the pressure from day one. The intense challenges ahead of her are mounting.

If the new PM wants advice about entering No 10 in troubling times such as today’s cost-of-living crisis and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Major is surely the best person she could speak to.

“My inheritance was unpromising,” Sir John writes in his autobiography. “We were on the eve of a war. The economic bubble of the 1980s was bursting. Inflation was approaching double figures. Interest rates were at 14 per cent. Unemployment had begun to rise by 50,000 a month. House prices were falling. The economy was in the first phase of acute recession. Ahead lay a collapse in growth, equity values, sales and confidence.”

Added to all that: “The poll tax was deeply unpopular and could not survive, although no alternative source of local taxation was in sight.”

Truss will have to begin preparing for her first Prime Minister’s Questions, scheduled for midday on Wednesday. The PM can change the timings, however – it used to be twice a week for 15 minutes until Blair replaced it with a single 30-minute session.

Nuclear war orders

The greatest responsibility for a new prime minister is surely the “letters of last resort” they must write to the commanders of the UK’s Trident-armed submarines. These instruct what the captains should do if a nuclear attack is launched on Britain and all communications are cut off.

David Cameron describes this experience in his autobiography. “A senior naval commander comes to your office to brief you on the options and the process,” he explains. “You’re then left alone with a series of alternative letters, and you decide which instructions to give. The others you shred in a giant, industrial-sized shredder which seems to appear in your office that morning.

“It is the moment when the full seriousness of your responsibilities as prime minister come home to you. I had spoken with John Major about the approach he had taken, and I had decided on what I believed to be the right course of action. But even so, I sat and stared at the cold words on the page, trying to imagine the scenario in which one of our submarine commanders had to open one of my letters.

“As I handed over the chosen letters to the officer – letters I prayed would never, ever, have to be opened – one of the envelope’s seals popped open. A call for Pritt Stick and Sellotape was rapidly answered. An absurd moment in such a solemn process.”

Calls with foreign leaders

The stream of phonecalls from international counterparts must seem endless for any PM in their first few days. Take Brown’s list. In a traditional symbol of the “Special Relationship”, his first phonecall was with the US President, then George W Bush. Then came the leaders of France, Germany, Ireland and Italy, followed by South Africa, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, China – and then came chiefs of the European Commission, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization.

On his first evening as PM, Cameron was called by Barack Obama who told him: “Enjoy every moment, because it’s all downhill from here.” While it’s hardly the joke of the century, this comment tickled Cameron, who admitted he “would use the same line when ringing other presidents and prime ministers after their election victories”.

Truss could be in for an awkward conversation with France’s current leader, Emmanuel Macron, after she said in a recent hustings that the “jury is out” on whether he is a “friend or foe” to the UK. Her combative approach to Brexit in Northern Ireland could also make things tense with Joe Biden, who wants to preserve the Good Friday peace agreement at all costs.

The first big international summit for the new PM will be the G20 in Indonesia in November, when Vladimir Putin is due to attend. Rishi Sunak had said he would boycott the meeting because of the Russian President’s invasion of Ukraine, but Truss says she will confront him. She could also be in for a difficult time with China’s President Xi Jinping, after reports suggested she could give his country the same status as Russia, labelling it an “acute threat”, which Beijing has called “irresponsible”.

Cabinet choices

A new prime minister will normally appoint up to six of their 23 Cabinet positions on their first day in office, says Haddon. The rest of the Cabinet tends to be revealed the next day, with dozens of other ministers announced a day or two later. But with the first meeting scheduled for Wednesday morning, Truss may try to hurry up her appointments.

This process might seem slow to TV viewers who are bored by day four of “breaking news” tickers about the new Minister for the Pacific (yes, that’s a real role) or the latest Lord in Waiting, but this is rapid compared to the process in other countries. Haddon advises that “a new prime minister should not rush this process”, as mistakes can quickly lead to failing policies and rebellious colleagues. All members need to be interviewed by officials to ensure they do not have any conflicts of interest.

The PM can also create or abolish government departments if they wish, like how Johnson merged the Department for International Development into the Foreign Office.

Truss is rumoured to be lining up Kwasi Kwarteng as her chancellor, Suella Braverman as home secretary and James Cleverley as foreign secretary. She is thought to be considering a return for former party leader Iain Duncan Smith, with her leadership rival Penny Mordaunt – who backed Truss over Sunak – as party chair. Several figures from the right of the party could join them, including Lord Frost as cabinet secretary.

Decisions like these could have ramifications for years to come. Just look at Theresa May’s appointment of Boris Johnson as foreign secretary in 2016, when he appeared to be entering the political wilderness after being stabbed in the back by Michael Gove and dropping out of the Tory party leadership contest. The position allowed him to regain influence before resigning and helping to bring May down. Would he have become PM without the boost she gave him?

It’s not just about who the new PM picks. It’s also about who they leave out. In a divided party which her colleagues say needs to be reunited, Truss could face internal opposition from an “awkward squad”, with Michael Gove and Dominic Raab among the current ministers expected to be left out. Sunak has been deeply critical of her tax plans; his allies say he’ll stay in Parliament – meaning another high-profile potential dissenter on the backbenchers – but others think he could walk away from politics.

Gordon Brown, who replaced almost half of Tony Blair’s final Cabinet, “did not want ministers who were resigning or being sacked to endure the glare of cameras as they walked along the street to and from No 10”, so he made his appointments at his office at the House of Commons, staying there until almost midnight on his first day in charge. This sounds like a useful tip for Truss.

Something else the new resident of No 10 will share with John Major is uncertainty about their angry predecessor. He writes of how Thatcher “felt dispossessed, cheated and betrayed” after being ousted by her Cabinet in 1990, much like how Boris Johnson is said to feel now.

Truss will have to be wary of those close to Johnson, who has urged his party to back its new leader but has not ruled out attempting to make a political comeback. Major saw how “lesser men than those who had once advised [Thatcher] now poured poison in her ear”, turning her against him.

No 10 staff

Besides the Cabinet, there are scores of political staff members to be appointed, working alongside permanent civil servants in running No 10. Truss will probably want a Chief of Staff and a Director of Communications, two roles introduced by Blair in 1997, as well as a Head of the Policy Unit and a Political Secretary. But leaders can change the structure and roles inside No 10 and the Cabinet Office. They may also choose to keep some of their predecessor’s staff to ensure some continuity; Cameron retained Brown’s Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell and No 10 Permanent Secretary Jeremy Heywood.

These appointments can become hugely controversial – just look at Dominic Cummings. His role as Chief Adviser to Johnson “certainly gave an impetus to that government, given where they were on Brexit and road to the December general election”, says Haddon. But his breaking of lockdown rules meant in the end he was hindering more than helping, and since his resignation he has become one of Johnson’s fiercest critics.

Cameron was also troubled by his choice of former News of the World editor Andy Coulson as his Director of Communications because of his part in the phone hacking scandal, which led him to quit in 2011.

“Part of the problem for new prime ministers who have already been in government is that they’ve built up a team of people who they feel responsible to and they’ve got to give them jobs,” says Haddon. “They’re often thinking about this loyal cast of characters rather than about what will make an effective centre for government.” She adds: “A key appointment is the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster – the enforcer role which Kit Malthouse has been doing recently and David Lidington did for Theresa May.”

It’s also up to the PM how they work with their team and what decisions they delegate. Haddon writes: “In the early May premiership, her chiefs of staff Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill would each go over all issues before it went to the prime minister. But May would herself then go through them again in detail. This caused bottlenecks that resulted in frustration elsewhere in government.”

Policy decisions and political gambles

New leadership teams like to announce a raft of ambitious policies soon after taking power. The Blair government gave independence to the Bank of England less than a week after winning the 1997 election, among many other bold moves.

“The disadvantage of a new government is lack of experience in governing,” Blair later wrote. “It is also the advantage. Its very innocence, its immaturity, the absence of the cynicism that comes from perpetual immersion in government’s plague-infested waters, gives it an extra ordinary sense of possibility… You can never quite recapture that amazing release of energy and boundless ‘derring-do’ that comes with the election of a fresh team.”

This energy is harder for a PM replacing a party colleague after they resign. Yet within three weeks of taking over from Blair in 2007, Brown proposed 23 new laws on subjects ranging from climate change to counter-terrorism – doing his best to look fresh after a decade in government as Chancellor.

After a general election, voters know most of what to expect from the winning party’s manifesto – and opposition leaders who win elections have usually spent years arguing what they would do. But when a new figurehead comes in midway through an election cycle, especially when they did not begin a leadership contest as the frontrunner, there is sometimes more mystery despite the many ideas they have floated to win support.

Truss will announce an emergency budget, in which she and her new chancellor will be under pressure to somehow simultaneously help families struggling with rapidly increasing bills, tackle inflation and reassure business. Truss’s priority is to cut taxes, despite worries about who this would benefit most and what it would cost – and the former Remainer might underline her Brexit credentials by triggering the controversial Article 16 in a legal battle with the EU over Northern Ireland’s border.

There are concerns that Truss has not been clear enough about her policies on the cost-of-living crisis. But her camp claims she has been delayed by a lack of information from the Treasury, which has held no meetings with her team.

The new PM will also face calls for an early general election, with 51 per cent of voters in favour of this and only 20 per cent against. It worked for Johnson in 2019, who called an election within months of entering No 10 and secured a big majority. But given the country’s economic problems, Truss will probably resist, thinking instead about the lesson of May. She looked bold in calling an election in 2017, less than a year into her premiership, but a poor campaign led to her losing the Tories their majority in Parliament. What the new leader really shouldn’t do is flirt with the idea of an early election but then back away, as Brown did in 2007, as this will lead to accusations of weakness.

Realising the true intensity of the job

Even experienced politicians sometimes fail to realise just how intimidating, demanding and unrelenting the job of leading the country really is until their first day, says Haddon. “Even when they’ve been a minister, there is a failure to appreciate just how all-encompassing the role of prime minister is.”

Blair recalled: “My predominant feeling was fear, and of a sort unlike anything I had felt before.”

Not everyone feels like this. When Winston Churchill recalled the end of his first working day as prime minister, he claimed to have felt a sense of belonging inside No 10, despite the worrying news of Nazi Germany invading Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg that same morning in 1940.

“As I went to bed about 3am, I was conscious of a profound sense of relief,” he wrote in his 1948 memoir The Gathering Storm. “At last I had the authority to give directions over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial… Although impatient for the morning, I slept soundly.”

Major sought to be as humble as possible, writing: “I did what I have always done with any new job. I played the promotion down as of little consequence, and got on with the job. I remember that in the week I became prime minister I arrived home for the weekend, and Elizabeth [his eldest child] teased, ‘Anything happen this week?’”

Cameron remembers he “felt exhausted, elated – but strangely at ease… because there is such a warmth from all the people in that building”, and thanks to the “familiarity” of a building where he worked in his twenties as a researcher and a special adviser. “As well as feeling daunted, honoured and excited by the prospect of being PM, I felt ready”.

But Haddon believes many fresh incumbents of the office risk feeling overwhelmed at the start. “You are responsible for every part of government. Everyone wants a piece of you, not just domestically but internationally as well. Foreign policy increasingly takes up a lot of your time,” she says.

Then there is the media scrutiny, which Truss has sought to avoid so far but will have to face up to with the countdown to the next general election already beginning.

“To say it’s a 24/7 job is not really doing it justice in terms of the huge pressure and workload,” says Haddon. “Anyone from the outside, even if they have had a lot of contact with No 10, always thinks: ‘I would do things differently’. It’s only when you’re inside that you realise just how massive a job it is.

“We put a lot of pressure on the individual in the UK, we don’t have anything like the size of support team you might get in the White House or other government administrations. Huge numbers of decisions come up to the prime minister and they can become a bottleneck if they can’t manage that workload and can’t make decisions.”

For the Record by David Cameron (HarperCollins), My Life, Our Times by Gordon Brown (Vintage), A Journey by Tony Blair (Cornerstone) and The Autobiography by John Major (HarperCollins) are all on sale now

Twitter: @robhastings

Maurice Saatchi: I used to adore capitalism – then I had lunch with Margaret Thatcher