Hundreds more people could be cured of epilepsy in the UK every year after scientists made a discovery about the causes of the condition.

They are also confident that their discovery paves the way for greater understanding and better treatment of a range of other brain conditions from Parkinson’s to severe depression in the longer term.

For the first time, researchers at Great Ormond Street Hospital have identified how differences in the way the brain is wired can make children more susceptible to seizures.

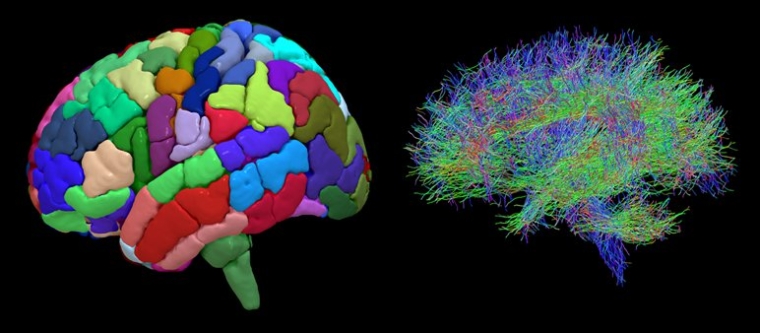

They have done this using a new imaging technique, known as diffusion MRI, to examine the brain areas removed during operations on 52 children with epilepsy.

This has enabled doctors to map the brains of people with epilepsy in unprecedented detail by focusing in on the neural connections that link, or wire together, more than 200 different parts of their brains.

This in turn has allowed them to identify unusual patterns of ‘wiring dynamics’ that can cause seizures in individual cases.

And more generally it has taught them that children with epilepsy have more connections between different areas of the brain – effectively binding them together more strongly – than those who don’t have the condition.

Furthermore, they have discovered that children whose seizures stemmed from multiple areas of the brain had greater differences in wiring than those with seizures stemming from only one area in the brain.

“This has the potential to reshape the way we think about epilepsy surgery. We hope that through this technology and analysis we can enable many more children with the condition to benefit from life-changing surgery and treatment,” said Aswin Chari, a surgeon scientist at the Great Ormond Street Hospital, who led the research.

“There are a whole load of children who have epilepsy and you scroll through an MRI scan and you clearly perceive that there are abnormalities on that scan.

“But there are also a whole load of patients with epilepsy for whom you can’t see these abnormalities. So we don’t know where the epilepsy is coming from. The big finding here is that even in visibly normal scans you can detect these wiring difference in children with epilepsy,” he said.

“So on an individual level, surgeons could in the future be better able to accurately identify which part of the brain to cut out based on that person’s wiring dynamics – combined with the greater understanding of epilepsy overall that these maps have brought,” Mr Chari said.

He says more research is needed before these kind of ‘wiring diagrams’ can be used to guide operations and cautions that this may throw up unforeseen problems.

However, he says “three to five years is a realistic timescale” for their use in the health service with the first clinical trials of the technology expected within three years.

About 600,000 people in the UK, close to one in 100, have epilepsy.

About three-quarters of them respond well to epilepsy treatment but about a quarter are resistant to drugs.

Of the remaining quarter about 10 to 20 per cent have an operation to remove parts of their brain.

Of those who don’t, this is usually because doctors think surgery wouldn’t help or may be too dangerous or because the patients don’t want it.

And of those who do have an operation, about 60 to 70 per cent are successful, meaning they are largely or completely cured of seizures.

Mr Chari hopes that the success rate will rise to “80 to 90 per cent” when the findings from his study are incorporated into surgery – although he points out it is too early to make a confident prediction and cautions that the change could be much smaller or even non-existent.

With about 400 to 500 operations on children a year in the UK – and three to four times that number for adults – this could mean hundreds more successful operations a year, Mr Chari says, since adults can also benefit from any changes in procedure.

And in some cases, the maps could even help rule out patients for surgery who may be unsuitable if, for example, the wiring abnormalities were widespread across the brain meaning an operation wouldn’t help.

Children just a few months old can have surgery if the epilepsy is bad enough, although this is rare he says – with three years and above much more common.

What other conditions could benefit from the breakthrough

In the longer term, Mr Chari hopes similar mapping techniques can be used to develop ‘wiring diagrams’ to improve understanding and treatment of a range of other neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s Disease, Obsessive Compulsive disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, severe depression and psychosis.

“The concept of viewing the brain as a network has been used in lots of neurological disorders, from things like movement disorders – so Parkinson’s Disease, which affects lots of older people – to neuropsychiatric problems, such as obsessive compulsive disorder.

“So there’s a growing group of brain-related disorders which other research is showing is also to do with the brain networks of the wiring diagram being abnormal in different ways,” Mr Chari says.

“And if we can harness a way to say ‘if this is how it goes from normal to abnormal’ we can then translate the abnormal back to normal again and therefore help with a whole host of brain-related conditions. Finding out more how they work which could potentially lead to better treatment and operations.

“And it’s not limited to operations. If we can find medications that target specific brain networks or that modify the network in certain ways there’s huge potential to even avoid surgery.

“Diffusion MRI allows us to split the brain into 200-plus different areas. It then allows us to see how abnormal the wiring is in these different areas. We can then decide, for example, that all areas above a certain threshold of abnormality should be resected [cut out] and therefore, it may alter the surgery plan [for epilepsy and potentially other disorders].”

Back to epilepsy, Mr Chari says the new technique may also be able to help doctors to use alternative new techniques to curb seizures that are still very rarely used and involve electrical stimulation of the affected parts of the brain by helping them to better target the pulses. These are less intrusive than the current method of cutting out brain.

What the experts are saying

Experts not involved in the study welcomed its findings.

“This has the potential to transform the lives of children with epilepsy and other brain conditions,” said Kiki Syrad, director of impact and clinical programmes at Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity.

Ley Sander, Medical Director at the Epilepsy Society and Professor of Neurology at UCL, said: “This important study suggests there may be underlying differences in the architecture of brain networks in children whose seizures do not respond to current medication, enabling the brain to transition more readily into a state of seizures.

“A network-based approach to exploring the physiological processes associated with epilepsy will hopefully lead to better treatment options in the future.”

Jay Shetty, consultant paediatric neurologist, NHS Lothian and an academic at Edinburgh University, said: “This will be a very good concept and has great potential although it needs further evaluation in different setting and population for this to use in healthcare settings in routine practice.

“This is an interesting and exciting area of work on network organisation of white matter microstructure. If these findings are reproducible in larger datasets, this can be an additional tool in precision planning and treatment of epilepsies and also neurorehabilitation.”

He said Mr Chari’s hope to push up the success rate of epilepsy operations to 80 to 90 per cent was a “bold claim” – adding “we need more robust data and validation in larger population to make such claims”.

Mr Chari agrees that more research is needed but remains hopeful he can hit that figure, saying: “This is why you ask independent people. It’s probably too early to say how much it could improve the success rate by, but we do believe that epilepsy is a ‘brain network’ disease and therefore, thinking about wiring diagrams will hopefully lead to an improvement. I agree that 80-90 per cent is a bold claim, but I’m not sure how to temper it.”

The research was published in the journal Communications Biology. It also involved King’s College London, the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, the University of Pennsylvania and Nemours Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida.

Case study: Millie Power

Millie is a nurse on Great Ormond Street Hospital’s Koala Ward and is responsible for looking after children with epilepsy.

She has her own experience of epilepsy having been diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis complex when she was a baby – a rare genetic condition that causes epileptic seizures. In 2020 when she was 26, she had surgery to remove part of her left temporal lobe and her hippocampus, the parts of the brain found to be causing her seizures.

Her operation was a success and Millie is now seizure free and enjoying the new freedom this brings.

“I was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis complex when I was a baby after having my first seizure,” she said. “Back then I was having tonic-clonic seizures. Medication stopped those seizures, but I then started having two to three focal seizures a week – these are a bit less angry.

“Epilepsy has always been a big part of my life. As well as having the condition myself, I work on Great Ormond Street Hospital’s Koala Ward, which is a neurosurgical ward, and I’ve always done charity work linked to epilepsy. I was probably very naïve as to how much epilepsy affected me.

“As a child no one ever gave my parents the option of surgery, but in adulthood, because of my job as a nurse and my interest in epilepsy, I found that I may be eligible for surgery. I eventually had the surgery in July 2020.

“When I stopped having seizures post-surgery, I felt like I’d lost a bit of my identity. I almost had to remind myself I still have the condition. It’s like someone who brushes their teeth twice a day being told they no longer need to brush their teeth. I remember saying to my husband, ‘What do normal people think about?'”

While life post-surgery has been a big adjustment for Millie, she reflects on the change she’s seen in her mental wellbeing.

“My mental wellbeing and energy levels have massively improved. I will now go for really long walks, sometimes for two or three hours,” she said.

“Two years ago I wouldn’t have even gone to a supermarket on my own when I was feeling unwell. There’s a lot more freedom to my life that I didn’t realise I was missing beforehand.

“It would be amazing if the new research conducted by Mr Chari and his team means more children are given the option to have the surgery when they’re younger. As children’s brains are still growing they can recover more quickly than an adult brain following treatment. I’ve been on antiepileptic drugs for so long, that I will never fully come off them. If surgery had been an option when I was younger, I could have stopped the medication and my brain would have grown to not need it.”