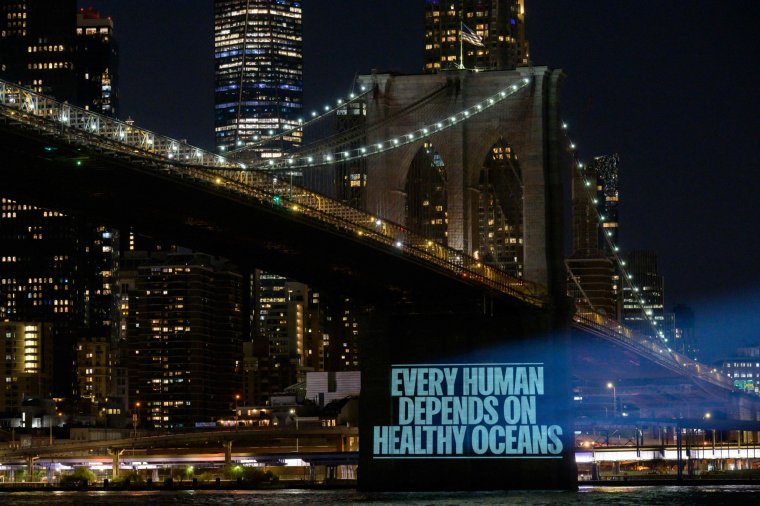

Late on Saturday night in New York, negotiators finally concluded the first major international treaty to protect the world’s oceans, after two decades of negotiations.

It came after a marathon overnight session that pushed the negotiations beyond the official deadline for a deal and was the third such attempt in under a year.

Coming on the back of so many other international environmental agreements, the treaty may seem unremarkable. It is, however, a landmark moment.

“The treaty is essential if we are to protect 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030,” Charles Clover, executive director of the Blue Marine Foundation, told i, referring to an agreement made at the Cop 15 biodiversity conference in Montreal last year.

Laura Meller, an oceans campaigner for Greenpeace Nordic, called it a “historic day for conservation and a sign that in a divided world, protecting nature and people can triumph over geopolitics”.

While environmentalism has been on a roll in recent years, the oceans remained a huge but neglected area.

“We only really have two major global commons – the atmosphere and the oceans,” said Rebecca Helm, a marine biologist at Georgetown University. The oceans may receive less attention, but they are “absolutely critical to the health of our planet”.

They are an enormous carbon sink, capturing around a quarter of all the carbon dioxide pumped into the atmosphere, while the oceans are also essential for regulating the global climate and produce around 15 per cent of the protein consumed by humans and create half the oxygen we breathe.

Until now, they have been regulated by an outdated patchwork of agreements that have left much of the open ocean at risk from overfishing, exploitation, pollution and climate change.

The 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea was the last major international treaty dealing with oceans and is the foundation for much modern maritime law, helping to clear up disputes over territorial waters.

It formalised the concept of the high seas, also known as international waters, in which all countries have the right to fish, perform research and sail vessels.

While important to global economies, these international waters rely on often poorly enforced and difficult-to-agree international laws to protect their natural environment.

Just 1.2 per cent of international waters are protected areas, despite representing 64 per cent of the world’s oceans.

This has led to examples like the Galapagos Islands, where a strict marine reserve has helped create an environmental haven within Ecuador’s territorial waters, but enormous fleets of Chinese deepwater fishing vessels are able to get as close to the edge of international waters as possible while hoovering up fish life.

“The treaty provides a framework for creating marine protected areas on the High Seas for the first time” Mr Clover explained to i.

Previously, any protection of high seas areas relied on regional bodies that failed to reach consensus. The new treaty knits together that patchwork of agreements and organisations into a unified system.

“There will of course be a delay while the requisite number of countries ratify the treaty but as the negotiators have given the task to existing UN institutions – such as regional fisheries management organisations – there really is no excuse for not starting immediately on site selection,” Mr Clover said.

“There are some very rich areas that need protecting, for instance, the Sargasso Sea, the Lost City and the Walvis Ridge in the Atlantic and the Thermal Dome in the eastern central Pacific. The last is a hotspot for sharks, turtles and all sorts of creatures so will be high on anyone’s list.”

The treaty will also require periodic, Cop-like meetings of the parties that will hold members to account.

Crucially, the treaty establishes ground rules for conducting environmental impact assessments for commercial activities in the oceans.

“It means all activities planned for the high seas need to be looked at, though not all will go through a full assessment,” said Jessica Battle, an oceans governance expert at the Worldwide Fund for Nature.

Among the many threats to our oceans, one that has been deeply troubling scientists and conservationists is the looming prospect of deep-sea mining.

The transition to renewables is driving a rise in mineral prices and many companies are already exploring the possibility of mining them from the ocean floor.

The Convention on the Law of the Seas established the International Seabed Authority, which for nearly three decades has been meant to be drawing up rules for deep-sea mining but has so far failed.

Until those laws are agreed mining is meant to be banned, but a loophole in the treaty means that any signatory could trigger a two-year countdown to mining being allowed.

Scientists have warned that the pollution and noise from such activities could cause irrevocable damage to marine life.

More from Environment

I'm an environmental expert - this is how Labour can fix the rivers crisis

Will water bill hikes actually be enough to tackle the sewage crisis?

A study published last month in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science found that the noise from mining could interfere with the communication of whales, dolphins and porpoises, impeding their ability to feed, navigate and stay close to their young.

The new treaty does not end that threat, said Ms Meller of Greenpeace, but it is a “starting point” for defending the oceans.

Helen Scales, a marine biologist and author of The Brilliant Abyss, told i: “If the industry is allowed to go ahead, the focus will be on the high seas and there are still no reassuring plans in place to safeguard the environment from the catastrophic damage mining could cause. This new treaty should make it easier to protect fragile species and habitats in the high seas from future mining plans. This is a crucial step in the right direction and now we need to act fast.”

The treaty will now need to be ratified, with each signatory country having to do so individually via its own domestic processes. The Convention on the Law of the Seas took 12 years to come into force, but campaigners are optimistic the new treaty will be implemented quickly.

A leading group of nations, including the US, UK, China and EU as well as many developing countries, known as the High Ambition Coalition, helped broker the final treaty and will now push for its swift ratification.

The EU has already pledged £35 million (€40 million) to facilitate its ratification and rapid implementation.

Dr Scales said this was a “hopeful moment” for the oceans. “I hope we’ll look back at this as the start of a new era when humanity prioritises the health of the ocean, and not just how it can be exploited.

“The high seas treaty shows that people are now looking out beyond the horizon and recognising that these remote, hidden swathes of ocean space are critical for the health of the entire planet. Most of us will never go there or see the high seas but they matter for everybody.”

Maurice Saatchi: I used to adore capitalism – then I had lunch with Margaret Thatcher