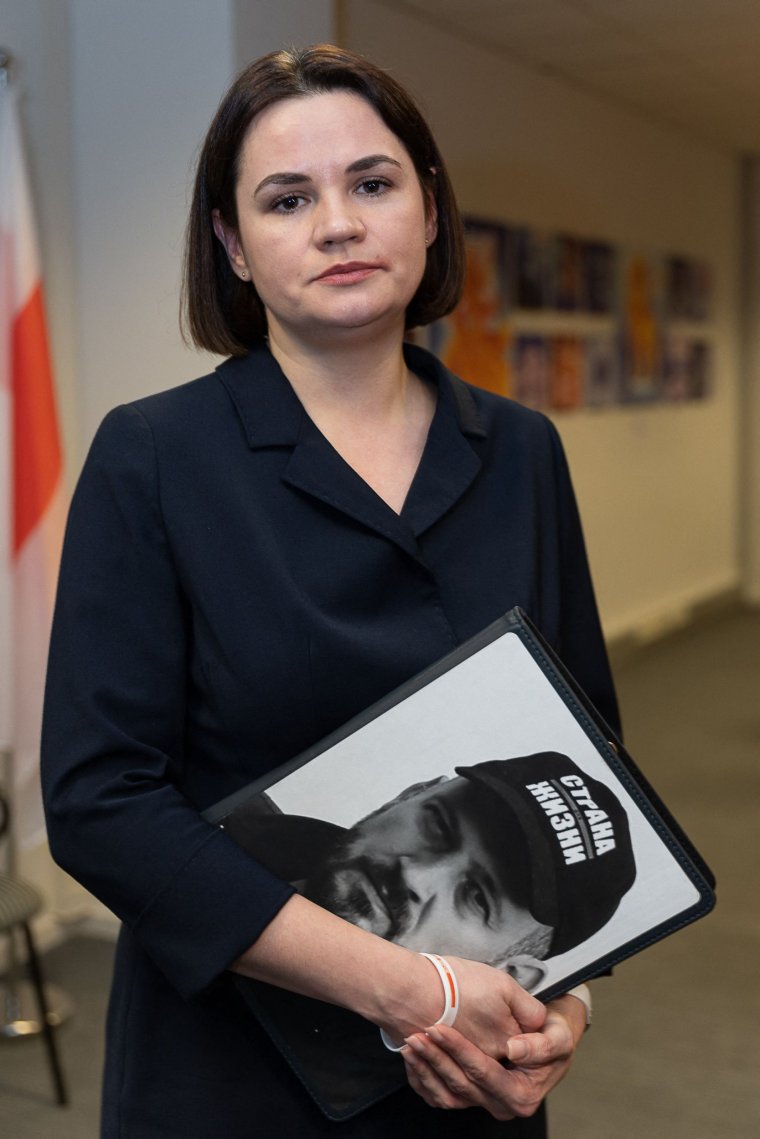

Belarus’s exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya winces when she’s lionised as a Joan of Arc figure standing up for the oppressed masses. She certainly never sought praise for her courageous resistance to the dictatorship in her home country.

“It’s like a weight on your shoulders,” she says mournfully. “It might seem extraordinary to some. It might seem exciting. But when you feel the pain of people in prison, or of people who are scared, then you can’t enjoy what you have at all.”

Ms Tsikhanouskaya is in Brussels, a regular stopping point as she continues to rally the European Union to sanction and isolate Alexander Lukashenko, Belarus’s authoritarian president. Speaking to i in the newly opened Democratic Mission of Belarus, she has just met key figures in the European Commission and the European Parliament, urging them not to forget Belarus’s noxious role in the war in Ukraine. For her, Mr Lukashenko, a dictator who has ruled Belarus since 1994, is merely a minion of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin.

“For many years, Lukashenka could say, ‘At least we are not at war,'” she says. “But now he’s a participant, an accomplice. He has played this last card and he is seen as a puppet of Putin.”

Ms Tsikhanouskaya, 40, has been a beacon of freedom and democracy for almost three years, after standing in the Belarus presidential elections in the summer of 2020. She only ran after her husband, Sergei Tikhanovsky, an activist and YouTuber who planned to run for president himself, was arrested.

The official election results gave Mr Lukashenko a victory of 80 percent, but unofficial tallies made her the clear winner. In any case, he ordered police to crack down hard on protesters. Ms Tsikhanouskaya fled into exile in Lithuania with her two children. But Mr Lukashenko’s strongman stance is wearing thin, she says.

“He can’t control the situation in Belarus anymore,” she says. “The regime is very fragile at the moment. There is this expression that a regime seems invincible 15 minutes before it collapses. It might seem monolithic, but it is not. I don’t know when, but Belarus will be free one day.”

Mr Lukashenko is Mr Putin’s staunchest ally, and he let pass Russian troops through his country last year so they could attack Ukraine from the north. He has not committed soldiers of his own to the war, and for good reason, Ms Tsikhanouskaya says.

“The only reason he is not doing it is because he fears the people,” she says. “The regime knows and Putin knows that our regular army doesn’t want to be involved in this. And even if an order for mobilisation is given, Lukashenko knows that people will not fight, that our soldiers will defect or hide or change sides.”

But she is disturbed by Mr Lukashenko’s eagerness to submit to Mr Putin. “We see this creeping occupation of Russia not only in the military sphere but also in cultural in media, in economic and political spheres,” she says.

Her message in Brussels is simple: with the future of Europe being decided on the battlefields of Ukraine and in the Belarusian underground resistance, how far will the EU go to defend its values? She has pushed for more support for exiled opposition, for campaigns to counter the regime’s propaganda, and for tighter sanctions to prevent Belarus from sneaking its potash into the EU.

She does not see herself competing for attention with Ukraine. “Yes, the world is focused on Ukraine, but we fully support this. Ukraine is fighting for what we in Belarus are fighting for too,” she says. “I don’t feel that Belarus is being abandoned or forgotten.”

More on Belarus

Outside Belarus, Ms Tsikhanouskaya is feted for her heroic defiance. Last year, she won the Charlemagne Prize, awarded for work done in the service of European unification. At the end of 2020, she was awarded the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

But last month, in her home country, was put on trial in absentia for treason. She shrugs at the threat, seeing it as just the latest crackdown during the decades-long dictatorship.

“I don’t have emotions about this. I see the stupidity of the situation. Of course, the regime wants to harm me emotionally and to put obstacles into my life,” she says.

“So they want to break my husband, they want to break me they want to break all the people who are fighting. But it doesn’t change anything for people, who just see the ugliness of the regime.”

Ms Tsikhanouskaya can only communicate with her husband through her lawyer, and in May it will be three years since she and her children have seen him. They receive his letters but can’t reply.

“My children get letters from him. My daughter can read his postcards, and she’s crying. It’s so painful to see,” she says

Ms Tsikhanouskaya was a rare Belarusian to have experienced life in the West during the Cold War: as a ‘Chernobyl child’, she was considered a health risk and was brought to Ireland in the wake of the 1986 nuclear disaster in neighbouring Ukraine. She stayed in Roscrea in Tipperary and was given medical attention, but also enjoyed life beyond the Iron Curtain.

What does she recall from her time there? “Smiling people,” she says. “It was such a contrast with Belarus because those were dark times. We did not have food or clothes, and everything was so grey around us. But I came to Ireland, and people were smiling, they were so polite. Life was blossoming, the shops were full of food, and there was a variety of clothes. And fantastic smells.”

And with that memory, she allows herself a little smile too.