It started with a promise. David Cameron, newly elected, vowed in the 2010 coalition agreement to stop sending LGBT asylum seekers back to countries where they face “imprisonment, torture or execution”. He pledged to “use our relationships with other countries to push for unequivocal support for gay rights”. Then, in defiance of his party, bolstered by the Lib-Dems, and to the amazement of many LGBT activists, he introduced same-sex marriage. The Tories, it seemed, were a-changin’.

Fast-forward 14 years – four prime ministers later – and the skies have darkened, grey clouds obstructing the promised rainbow.

Rishi Sunak vows instead to ‘Stop the boats!’, to send asylum seekers to Rwanda, regardless of whether anyone on those boats has been tortured for being gay, in spite of Rwanda effectively criminalising transgender people, or its officials arbitrarily detaining and beating LGBT people (according to Human Rights Watch).

In the Commons, Sunak makes jokes at the expense of trans people, even when he’s been told the parents of a murdered trans teenager are present.

His former home secretary, Suella Braverman, claims that people pretend to be gay in order to claim asylum. His “minister for common sense” Esther McVey pledges – when millions are struggling to afford food, rent, and heating – to ban civil servants from wearing rainbow lanyards and vows “there will be no more contracts for external diversity”.

His Education Secretary Gillian Keegan announces that teachers will be prohibited from discussing gender identity which “should not be taught in schools at any age’’. And his equalities minister Kemi Badenoch vows to change the Equality Act to make it easier to bar transgender people from single-sex spaces.

So what are we to think now? How do we assess the Tories’ overall record on LGBT rights since 2010?

Equal marriage was a piece of halo legislation that shone far beyond the ceremonies and the legal protection denied to same-sex partners throughout history.

It supported gay couples raising children. It helped equalise pension rights. It subverted the stereotype of the “lonely, tragic homosexual” into state recognition of lifelong same-sex love.

It meant no longer being excluded from the security heterosexuals enjoyed – however heteronormative the institution might be – and helped many couples feel fully respected; that they finally belonged.

Grandparents sat in wedding ceremonies witnessing gay couples being celebrated rather than, in their day, incarcerated.

Above all, it delivered a message to every Briton: the love between two women or two men is equal to anyone else’s, and therefore so are the people within that marriage. It helped fully humanise the once utterly demonised. It is unquantifiable how much joy this law unleashed, nor how deep its cultural impact.

But this jars so profoundly with the Tory Government’s recent policy announcement – to ban even discussion of gender identity in schools – as to invite the question: what on earth has the Conservative Party become?

Or, more accurately, to what have they returned? Muzzling teachers mirrors Thatcher’s darkest anti-gay policy, Section 28, that outlawed the “promotion” (which really meant any mention at all) of homosexuality in schools.

That infamous law, repealed by Labour in 2003, is for many synonymous with 80s homophobia. It meant that my generation grew up in a blackout. This occurred as adult gay men were dying of Aids, just when young people needed help, to talk, to ask. The “nasty party” that Theresa May identified in 2002 appears to be back.

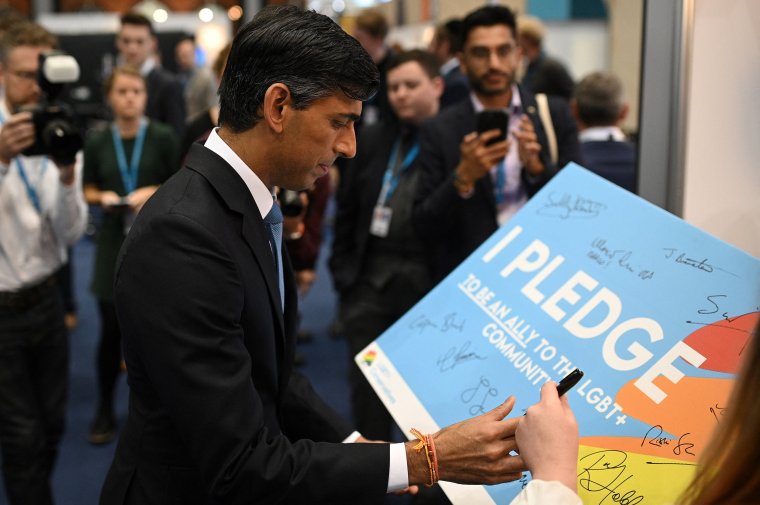

Sped up, then, the Tory record on LGBT rights over the past 14 years looks simple: they lit the torch of equality only to snuff it out. (Sunak, for instance, did not attend a Tory reception last summer to celebrate a decade since equal marriage passed into law, unlike Cameron. It’s hard to ignore the symbolism).

Slowed down and what’s noticeable is that nearly halfway through this period, Brexit – which emerged amid the rise of Trump, populism, and the resurgence of the right – marked the beginning of the party’s changing approach to queer and trans people.

Cameron quit, the “One Nation” liberal Tories became sidelined, and Brexiteers on the right of the party seized the reins just as storms of online hatred, bots, and disinformation began to rage, targeting sexual/gender minorities.

Eight years on from the Brexit referendum, the only thing being lit now by the Tory front bench is a culture war. Even the equalities minister Mike Freer MP quit in 2022 accusing his own government of “creating an atmosphere of hostility for LGBT+ people”.

But is it really this simple a story, from Technicolor to monochrome, rainbow flags to culture wars? After all, the majority of Tory MPs voted against same-sex marriage. And Cameron is now back as Foreign Secretary, happily working for Sunak. What, then, has gripped beneath the surface of the Conservative Party?

Two great forces emerge when you examine Tory policy and rhetoric on LGBT rights since they took office: money and power.

Let us begin with money. Austerity dominated the Cameron years (and most of the May ones), informing policies on LGBT issues more than anyone has admitted. Same-sex marriage might have been transformative but when the bill was passed, it had cost comparatively little. George Osborne as chancellor didn’t have to dig deep into his Timothy Everest suit pockets for that one. Instead, millions would be added to the economy by couples paying for their weddings.

But below the confetti lay a reality largely unnoticed, but which I reported at the time. Austerity disproportionately affected LGBT people.

According to a major study by London Metropolitan University, cuts from central and local government to charities and voluntary sector organisations caring for the most vulnerable within this community were “particularly pronounced”, the report said.

As the TV cameras were trained on wedding receptions, homeless, migrant, impoverished, physically and mentally ill queer people suffered, often invisibly.

Certain elements of progressive legislation and help for specific groups of LGBT people continued, however, from Cameron right through to 2023. The introduction in 2017 of “Turing’s Law” (an amendment to the Policing and Crime Act), which pardoned those convicted of homosexuality before decriminalisation? Important and long overdue.

The huge LGBT survey published by the government in 2018? An invaluable resource that could be used to inform policy (if the political will is there). Partially lifting the ban on gay men donating blood in 2020? A good step forward.

But to trace the progress made on LGBT issues over the past 14 years is to uncover a striking pattern. Each time the government inched forward it cost next to nothing. None of the above bothered the coffers much. When the ruling party stalled on further help or protection for this minority, money was often at play.

This pattern becomes even clearer when certain issues present solutions both cheap and costly. The 2023 apology given to veterans fired from the armed services for being lesbian or gay? Free. The compensation scheme to repay these victims for their loss of income, loss of mental health, and loss of pensions? Absent. Poor, elderly, even dying servicemen and women, hounded, humiliated, and sacked due to state bigotry, are still waiting.

It is predictable, therefore, that still we have no movement on the “gay tax” on IVF which leaves same-sex couples having to fork out multiple rounds of private treatment before the NHS will fund the three rounds that heterosexual couples already enjoy. For equality to extend everywhere means coughing up.

But it is when money meets power that these patterns are best illuminated, particularly regarding transgender people.

From 2016 onwards, a backlash against trans rights exploded internationally, online, on the streets, and in parliament. Among Tories, it became an intra-party war, the missiles from which are still landing on the general public.

But the story begins in January 2016, months before the Brexit referendum. The Women and Equalities Select Committee, chaired by Tory MP Maria Miller, published a radical, progressive report that made 35 recommendations to improve the lives of trans people.

These comprised a slew of legal changes, policy updates, and crucially, more support from the NHS for the healthcare of trans people (the numbers of referrals had already shot up by then):

“The evidence is overwhelming that there are serious deficiencies in the quality and capacity of NHS Gender Identity Services. In particular, the waiting times,” the report said.

Six months later, the government responded. While many of the legal and policy areas were considered with plans to address, monitor, or review them, healthcare concerns were treated differently.

Rather than vowing to heavily boost funding to cut the waiting times, the government argued that NHS England had already increased spending and that this alone wouldn’t fix the problem, which in fact was mostly caused by a lack of specialist personnel, it said, on which NHS England had already held a symposium.

In other words, the government appeared unmoved by the issues that would have cost the most – healthcare – but more responsive to cheaper, legal concerns. Enter Stonewall.

Spying an opportunity to grasp what progress might be winnable, Britain’s largest LGBT rights organisation focused more of its lobbying on legal changes, including easing the legal gender recognition process into a form of self-identification.

As the government considered its next move, some commentators, certain feminists and particular women’s groups raised fears about what easing the legal recognition process could mean – that men might exploit it to gain access to women’s spaces. The temperature of discussions raised exponentially.

Trans-inclusive feminists, including leading academics, disagreed, calling this a moral panic, but a wave of protest from social media to newspapers, from the streets to cabinet, took hold amid a rising international movement opposing trans rights, swelling from Trump’s America to Putin’s Russia to Bolsonaro’s Brazil. By now, the Brexiters, more natural allies of Trump and social conservatism, had more influence in cabinet. The dial was moving.

Imagine, though, if the government had prioritised healthcare as more pressing, despite the costs, delaying the legal issues. This would not have sparked such a storm of protest. It could even have encouraged an empathetic conversation about the suffering experienced by people with gender dysphoria.

But by this point, May was having to appease the right of her party just to remain in power. She continued trying to make progress with the LGBT survey and the LGBT Action Plan and in July 2018 her now infamous promise to ban conversion therapy.

But ultimately power became more instrumental to policy than money. In her last year in office, May, already weakened by the calamitous 2017 election, clung on ever more shakily. The anti-trans factions in her party were more heavily concentrated in the Brexit wing, so any boldness was replaced with pragmatism. She couldn’t defy her party like Cameron did. And by July 2019 she was out.

Boris Johnson, whose kingmakers were also the Brexiters, then flip-flopped on the conversion therapy ban as criticism grew louder on his own benches, claiming it could criminalise parents or clinicians trying to explore other options, particularly with children who have gender dysphoria.

First, he cancelled the policy, then following an uproar, re-introduced it, only to exclude trans people. In response, three of the government’s LGBT advisers quit in 2022, the entire LGBT advisory panel was then disbanded, and when 100 LGBT organisations threatened to boycott the government’s first, much-feted, global LGBT conference (dubbed “Safe to be Me”), the government was forced to cancel it.

As the government’s popularity began to sink that year after the catastrophic Truss premiership, fear within the party gripped. Who to blame? Various public institutions appeared at odds with the Conservatives on social issues. Universities, the civil service, the NHS, even the police seemed to many Tories to be beholden to “woke” issues, by promoting progressive agendas, flying rainbow flags, and spending money on diversity initiatives. The Conservatives’ “war on woke” began.

Two years on, as members of Sunak’s cabinet became ever more critical of trans rights, the conversion therapy ban has been shelved. It would have cost nothing, but power now lies with the right of the party. Kemi Badenoch, tipped as the next leader, is its most prominent “gender critical” figure.

The announcement about the Equality Act, made by Sunak and promoted by Badenoch, was a promise to rewrite this law, so that protections on the basis of sex only apply to biological sex. It would mean trans people could be kept out of single-sex prisons, bathrooms, hospital wards, and sporting events.

The act currently provides protection from discrimination on the grounds of gender reassignment and already allows for certain exemptions if proportionate and for “legitimate aims”. But Badenoch deems this insufficient, claiming that “public authorities and regulatory bodies are confused about what the law says on sex and gender”.

Perhaps she would rather trans people did not go to the toilet, or did not require operations for cancer, or did not play sports. To her, and this government, trans people are not valued, included, or respected, but deemed a problem, a scapegoat, a worthy butt of jokes.

Meanwhile, those waiting times for trans healthcare? They’re now even longer than in 2016.

Instead of tackling this, Sunak’s party has issued guidance to schools telling teachers that “parents should not be excluded from decisions taken by a school or college relating to requests for a child to ‘socially transition’”. In other words, the government is encouraging teachers to out kids to their parents. And last month, Gillian Keegan banned private, licensed clinics from prescribing puberty blockers to under-18s.

With Sunak’s power crumbling, he has leaned into the culture wars, but what does this term really mean? It’s a euphemism. It means, in his case, the politics of prejudice. It means dog-whistling, it means justifying and enflaming fear about marginalised groups.

Which brings us right back to his stance on immigration. How to judge the Tory record on LGBT rights? By 2022, when the Prime Minister took office, 12 years after Cameron’s promise, asylum seekers were still more likely to have their claim refused if they sought refuge on the grounds of sexual orientation than for other reasons. And that was after we had witnessed the grim spectacle of Afghanistan.

When Kabul fell in August 2021, only a few dozen LGBT people, fleeing for their lives from almost certain murder by the Taliban, were airlifted out. By contrast, Johnson personally intervened to get pets out.

There was so much else that was never tackled. The rising rates of hate crimes, particularly for trans people. The collapse of the gay scene – a lifeline for millions – with huge numbers of LGBT venues closing amid rising rents and the cost-of-living crisis. And an overall feeling that Britain isn’t at the forefront of LGBT rights any more. Pride has turned to shame.

It’s more than a feeling. ILGA-Europe, the international LGBTQ rights organisation, each year ranks European countries in order of their laws and policies on LGBT rights. A decade ago, Britain was number one. Now it is 16th, behind Greece, Spain, and Belgium. From leaders to losers. Progressive laws to culture wars. Same-sex marriage to a new Section 28.

LGBT people, however, will always be here, regardless of the Conservative party’s changing whims. We survived the prison cell, we survived the street beatings, the political scapegoating, the religious “cures”, the endless hateful laws and lies, even the Aids crisis. We are no longer on the margins but within every family, every institution, every community – openly. Voters can see what the last 14 years have done to us. The darkened skies await a new dawn.

Grindr must act but there are darker reasons why children are on the dating app