In the years leading up to the birth of Ms., women had trouble getting a credit card without a man’s signature, had few legal rights when it came to divorce or reproduction, and were expected to aspire solely to marriage and motherhood. Job listings were segregated (“Help wanted, male”). There was no Title IX (banning sex discrimination in federally funded athletic programs); no battered-women’s shelters, rape-crisis centers, and no terms such as sexual harassment and domestic violence.

Few women ran magazines, even when the readership was entirely female, and they weren’t permitted to write the stories they felt were important; the focus had to be on fashion, recipes, cosmetics, or how to lure a man and keep him interested. “When I suggested political stories to The New York Times Sunday Magazine, my editor just said something like, ‘I don’t think of you that way,’ ” recalls Gloria Steinem. “It was all pale male faces in, on, and running media,” says Robin Morgan, who was Ms.’s editor in the late eighties and early nineties.

But in the mid-sixties, feminist organizations such as New York Radical Women,Redstockings, and NOW began to emerge. On March 18, 1970, about a hundred women stormed into the male editor’s office of Ladies’ Home Journal and staged a sit-in for eleven hours, demanding that the magazine hire a female editor-in-chief. Says feminist activist-writer Vivian Gornick, “It was a watershed moment. It showed us, the activists in the women’s movement, that we did, indeed, have a movement.”

By age 29, Gloria Steinem had forged a reputation as a smart, pithy writer with her 1963 exposé in Show magazine about going undercover as a Playboy Bunny. She was a staff writer at New York Magazine when it debuted in 1968, along with Jimmy Breslin and Tom Wolfe. Radicalized by an abortion speak-out, which she covered for New York in 1969, Steinem started spending more time thinking, writing, and giving talks about feminism. She testified in the Senate in 1970 on behalf of the Equal Rights Amendment, and co-founded the Women’s Action Alliance and the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971. That same year, she helped launchMs. magazine,which became the first periodical ever to be created, owned, and operated entirely by women. A forty-page excerpt of its preview issue was published in the December 20, 1971, issue of this magazine. Here are the stories of the women who were there.

Gloria’s Living Room

In early 1971, Gloria Steinem and attorney/activist Brenda Feigen hosted a crowd of female journalists at two meetings in their respective apartments—Steinem’s in the East Seventies, Feigen’s in Tudor City—to brainstorm ideas for a possible publication for women.

Brenda Feigen (co-founder, with Steinem, of the Women’s Action Alliance, 1971): It was amazing: jammed with well-known women writers, journalists, and activists. All of them said, “We can’t get real stories about women published.”

Jane O’Reilly (contributor, 1971–90s): People were sitting on the floor, on chairs, hanging from rafters. When it came to all the topics proposed, it struck me as being like your first trip to Europe: You think you have to go to every single country because you might never get to go back.

Article Ideas From a Confidential Memo

Some Notes on a New Magazine (4/71):

*THE POLITICS OF SEX

*DON’T BELIEVE HIM WHEN HE SAYS POLITICS BEGIN IN WASHINGTON. POLITICS BEGIN AT HOME.

*HOW NOT TO GO THROUGH MENOPAUSE

*A SECRETARY IS AN OFFICE WIFE

*SOMEONE SHOULD HAVE LIBERATED PAT NIXON

*“OF COURSE, I’M ALL FOR EQUAL PAY, BUT … ”

*HOW MARRIAGE KILLS LOVE

Susan Braudy (co-editor/writer, 1973–78): After one meeting, Gloria said, “I’ve been thinking about a newsletter.”

Letty Cottin Pogrebin (co–founding editor, 1971–89) [Editor’s note: Letty is the mother of Abigail Pogrebin, the author of this oral history.]: There were lots of newsletters and radical broadsheets—things mimeographed on newsprint or paper towels—that never built an audience.

Feigen: I said, “What do you mean newsletter? You’re famous. We should do a slick magazine.” Gloria said, “I don’t know if there’s a demand for it.” I said, “Of course there is.”

Pogrebin: I think that being slick and being sold on newsstands was a stealth strategy to “normalize” or “mainstream” our message. Some feminists would have preferred the women’s movement to continue speaking to the converted.

Vivian Gornick (feminist and writer): For radical feminists like me, Ellen Willis, and Jill Johnston, we had a different kind of magazine in mind. We came out against marriage and motherhood. Gloria was uptown; we were downtown. She hung out with Establishment figures; we had only ourselves. It very quickly became obvious at that first meeting that they wanted a glossy that would appeal to the women who read the Ladies’ Home Journal. We didn’t want that, so they walked away with it.

In August 1971, New York Magazine editor Clay Felker offered Steinem, one of his early protégés, the opportunity of launching a new magazine in New York’s pages as an insert in its year-end issue.

Gloria Steinem (co-founding editor, 1971–present): We’d been crawling around on our knees trying to raise money, which was arduous. Clay said, “If you give me your first issue to choose the 40 or so pages I want from it, then I’ll subsidize the printing of the other 90 or 100 pages and we’ll put it out as a sample.” And that’s what we did.

Clay Felker, in an editor’s letter, 1971

“We at New York owe Gloria a great deal. She helped enormously in getting our magazine started … therefore we must … do what we can to help Gloria and her writing sisters get started.”

Steinem: It wouldn’t have happened without Clay.

Pogrebin: In those days, nothing happened without men. You needed one man to be nice to you and then maybe you could run with it.

Steinem: Clay gave me my first serious assignment when he was an editor at Esquire: a piece on the contraceptive pill.

Felker in the Washington Post, December 12, 1971: “She doesn’t like this story but I saw her standing outside my office one day and I thought she had great legs. I gave her her first bylined assignment and it was excellent.”

Nancy Newhouse (co–founding editor, preview issue): Clay wasn’t a feminist in the classic sense.

Pogrebin: He may well have had a crush on Gloria. Everybody did.

Patricia Carbine (publisher, 1972–87): What Clay and Gloria imagined was that New York would take on this idea of a feminist magazine as a one-shot. Gloria’s colleagues would produce the content; New York would pitch in with the designers.

Pogrebin: We called it the “Preview Issue” because it was a test to see if it would actually sell.

Milton Glaser (New York design director, 1968–77): We worked right out of the office and started simultaneously doing our weekly magazine. We really felt, all of us, that we were on the brink of a moment in time.

Newhouse: The art director, Rochelle Udell, and I were the two donkeys closing the magazine. Gloria gave each of us a silver ring afterward—which was the feminist symbol. I kept it for years. She’d come in the office, and we’d still be there at ten o’clock at night.

Joanne Edgar (co-founding editor, 1971–89): We had decided to charge $6 for an annual subscription because we wanted the magazine to be affordable. One of the financial advisers said, “You can’t charge $6—it’s a monthly, and you won’t be able to put out a magazine for that little money!” We didn’t have time to change the type—this was way before computers—so we just cut out the 6 and repasted it upside down to make it 9 dollars a year.

Newhouse: Clay and Gloria had knockdown arguments about the first cover. Clay wanted a photograph of a man and woman, back-to-back, tied to a big pole. The idea was that they’re tied together, struggling.

Steinem: His cover was negative … limited. It was focused on marriage, not on all women.

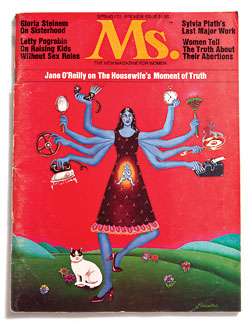

Pogrebin: Gloria preferred a drawing of a female figure with many hands, juggling the tasks of a woman’s life.

Steinem: It had a universality because it’s harking back to a mythic image—the many-armed Indian God image. And it solved our problem of being racially “multibiguous” because she’s blue: not any one race.

Glaser: I remember [the fight over the cover] as important because Clay was always yelling.

Proposed Titles for Ms. Magazine

Everywoman / Sisters / Lilith

Sojourner / Female / A Woman’s Place

The First Sex / The Majority

Steinem: “Bimbo.” I think we tried “Bimbo.” On the same principle as “Bitch” or whatever. We did try “Sisters” out on people, and they thought it was about nuns.

Pogrebin: We chose Ms. because it could be explained and justified—since “Mister” or “Mr.” doesn’t communicate a man’s marital status, why should women carry “Miss” or “Mrs.,” as if to advertise their availability as mates?

Rochelle Udell (art director, preview issue): It was an announcement. Using Ms. said, “I’m a feminist.”

Mary Peacock (co-founding editor, 1971–77): When Ms. started, you couldn’t pick up the phone and say, “Ms. Magazine,” because what people heard was “Mmzzz” and they’d ask, “What are you saying?” This would happen 25 times a day. So when we picked up the phone, we said each letter separately: “M-S magazine.” But gradually something changed—I could shoot myself that I can’t remember when it changed, because it was a huge watershed: Suddenly you could say “Ms.,” and everybody knew what you were talking about.

Feature: “The Housewife’s Moment of Truth,”

By Jane O’Reilly

“On Fire Island my weekend hostess and I had just finished cooking breakfast, lunch, and washing dishes for both. A male guest came wandering into the kitchen just as the last dish was being put away and said, ‘How about something to eat?’ He sat down, expectantly, and started to read the paper. Click! … In the end, we are all housewives, the natural people to turn to when there is something unpleasant, inconvenient or inconclusive to be done.”

Peacock: Jane O’Reilly’s piece struck a chord.

Suzanne Levine (managing editor, 1972–88): Every woman got it.

Steinem: Jane described a moment when a woman who’s been piling up things on the stairs to take to the second floor watches her husband walk around them as he climbs the stairs, and she thinks, He has two hands! It was a prototypal “click” of realizing unfairness.

O’Reilly: The “click” idea just came to me. I didn’t know it would be the best idea I’d ever had.

Feature: “We Have Had Abortions”

A statement signed by 53 women, including singer Judy Collins; tennis champion Billie Jean King; and writers Susan Sontag, Grace Paley, Anaïs Nin, Patricia Bosworth, Barbara W. Tuchman, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, and Gloria Steinem. The article included a card that invited women to fill in their own names and send it in to the magazine.

Levine: I am not sure I had told anybody that I had … It really was a big secret in my life. Within a minute, I knew I had to sign that coupon and send it in.

Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel (editor of the abortion petition): I like to think that that was a precursor to the many acts that led to the Roe v. Wade decision a year later.

Edgar: I went to Barbaralee’s apartment because we had to verify all of those names; that was not something you took lightly.

Pogrebin: I thought it was especially important because as a wife and mother of three, I could not easily be accused of being a “baby killer.” Almost all my friends had had abortions. I wanted everyone to admit it.

Diamonstein-Spielvogel: The person who created the greatest stir and the most international phone calls was Billie Jean King.

Pogrebin: She was assumed to be gay, so how could she possibly have gotten pregnant? People forgot that she was married for several years. Also many people stupidly assume that lesbians don’t care about any issues other than their own rights.

Nora Ephron (signed the “We Have Had Abortions” statement): I remember that Gloria called me and said they were doing a statement that was inspired by what the Danes had supposedly done during World War II, wearing Jewish stars, daring the Nazis to arrest them all. Seemed like a great idea. Over the years, the occasional journalist has asked about it and assumed it was to be taken literally and that I had had an abortion. Which I hadn’t. They didn’t really understand the spirit of the statement at all.

Feature: “Down With Sexist Upbringing!,”

By Letty Cottin Pogrebin

“Our twin daughters aren’t into Women’s Liberation … But living with Abigail and Robin, age six, is an ongoing consciousness-raising session for my husband and me … They are constant reminders that lifestyles and sex roles are passed from parents to children as inexorably as blue eyes and small feet.”

Karin Lippert (promotion director, 1972–81): Letty brought the voice of a mother into the mix. She figured out what was wrong with how the culture was treating kids. It sounds like such an easy leap now, but it was a new concept in those days.

Pogrebin: Anti-feminists tried to label movement women as man-haters, anti-family, anti-marriage. There were always plenty of married women within feminist communities, but they didn’t always have as much time as single women to devote to activism, so they weren’t as visible.

Feature: “Can Women Love Women?,”

Anonymous interview conducted by Anne Koedt

“I was flooded with a tremendous attraction for her. And I wanted to tell her I wanted to sleep with her. I wanted to let her know what I was feeling.”

Steinem: Clay and many magazine people told me not to include a lesbian article in the first issue—and so, of course, we did.

Feature: “Heaven Won’t Protect the Working Girl,”

By Louise Bernikow

“A female college graduate earns a few dollars more a year than a man with an eighth-grade education.”

Louise Bernikow (contributor, 1970s): The story was my politics-is-personal moment. I grew up knowing “girls couldn’t,” and when it came to being writers, I knew that I couldn’t be a reporter for the New York Times or Newsday; I could only be a researcher. But I had never put it together in terms of the pyramid that the story reveals.

“The median annual income for white females is just over $5,000 and for non-white women, $4,000 … There is no job safe from the perils and humiliations of sex discrimination.”

Bernikow: What the magazine did was give a whole bunch of writers a gig. You could build a career on having appeared in Ms.; it was huge in my life. I’ve even got tears in my eyes saying this.

Impact of First Issue

Though the editors had expected it to sit on newsstands for months after its January publication date (they labeled it “Spring,” so it wouldn’t start to look stale if it lingered), the preview issue sold out its 300,000 copies in eight days.

Steinem: I was definitely afraid of failure. I had been so worried that somehow it would do poorly and it would really damage the movement because it was so public.

Edgar: I do palpably remember the huge relief I felt when thousands upon thousands of subscriber cards came in after the preview issue.

Steinem: We had no money to advertise the preview issue, so we all went out on the hustings to talk about the magazine to the media. Jane O’Reilly will tell you the story: She’d never spoken in public, and I made her.

O’Reilly: I was so frightened. I remember the importance of losing seven pounds so I could fit into this pretty dress.

Steinem: I went to L.A., and I was on a radio call-in show when the caller said she couldn’t find the issue on newsstands. Afterward, I called Clay in a panic and said, “The magazine never got here! It never got here!” And he told me it had sold out.

Edgar: We were absolutely invigorated. These enormous mailbags would arrive every day.

Letter, January 1, 1972

Dear Gloria,

I’m twenty-three years old, I have two daughters and a perplexed husband. Perplexed because he can’t figure out what it is about woman’s position in this world that makes me so very angry …

Karen Mattox

Port Clinton, Ohio

Letter, January 28, 1972

Dear Gloria:

About Ms.—it’s fantastic! We haunted the newsdealer’s till it arrived.

Newsdealer (patronizingly): “Is this the magazine you girls have been waiting for?”

Us (proudly): “No. It’s the magazine we women have been waiting for.”

Gena Corea

Holyoke, Mass.

The Raleigh Times, January 1972

“Ms. Is Magazine for a Whole Woman,”

By Lineta Pritchard

“For the first time you can read a publication that expresses total female sentiment, not sentiment based on some male publisher’s assumption that all women like to read about recipes, beauty tricks, wardrobe wizardry and entertaining.”

Letter, February 9, 1972

I’m encouraging every young woman I know to subscribe—those who can leave their macramé long enough to use their minds.

Marjorie Bruce

Hollywood, Calif.

Pogrebin: Of course, there were going to be detractors, too. They were poised to strike.

Syndicated Columnist James Kilpatrick, December 1971: “[Ms. is a] C-sharp on an un-tuned piano,” a note “of petulance, of bitchiness, or nervous fingernails screeching across a blackboard.”

Harry Reasoner on ABC’s Nightly News, 1972: “I’ll give it six months before they run out of things to say.”

President Nixon to Henry Kissinger on White House Audiotapes, 1972

Nixon: [Dan Rather] asked a silly goddamn question about Ms.—you know what I mean?

Kissinger: Yeah.

Nixon: For shit’s sake, how many people really have read Gloria Steinem and give one shit about that?

New York Times Headline, March 22, 1972:

“In Small Town U.S.A., Women’s Liberation Is Either a Joke or a Bore.”

Syndicated Gossip Columnist Earl Wilson on the Ms. Launch Party at the New York Public Library, June 30, 1972

“Speaking of libraries, some Women’s Libbers were well stacked and some ain’t never been stacked and never will be.”

Carbine: We learned that Ms. was being removed from public libraries as unsuitable reading material.

Steinem: Abe Rosenthal at the New York Times told me that no one would ever hire me again as a journalist; I’d thrown away my career.

Carbine: After the preview issue, the essence of what Clay said was, “Okay, now that you’ve done the one-shot, what else is there to say?” Even he was skeptical.

Assembling a Staff

The original Ms. staff was composed of writers and editors who had been at the early meetings or who were later invited to contribute. In some cases, there were people who simply knocked on the door. Elizabeth “Betty” Harris volunteered to help Steinem raise money for Ms., became the magazine’s first publisher, and lasted less than a year. (Harris died in 1999.)

Pogrebin: Betty represented herself as the person who was going to bring in the money.

Edgar: She didn’t bring in any money.

Steinem: I realized how dumb I was when Clay did a credit check on Betty and discovered she was wanted by the sheriff in California for nonpayment of bills and she’d been fired from a previous job.

Edgar: She was not very easy to get along with. She didn’t like anyone who disagreed with her or anyone she perceived to be standing in her way.

Steinem: So Betty and I started going around, looking for [potential funders], and after a few weeks, I realized that everybody we were seeing were people I knew. She wasn’t bringing any names to the table.

Carbine: The prevailing thinking is there is no way this can go forward if Betty is part of it. So we said to Betty, “Given the positive results of the preview issue, there is clearly a magazine to be done. If you think you can do it, it’s yours.” We meant it. I think she spent a busy weekend with some of her friends mulling it over. She didn’t take the magazine.

Feigen: It was extremely important to Gloria and Pat that they resolve that internal dispute and not take the whole magazine down with it.

Carbine: We gave her all the income earned from that first issue [$36,000]: all the advertising and newsstand sales. It was a way to let her know that feminists don’t try to destroy each other.

Steinem: Pat did it to be generous. I did it out of fear. What Betty maintained then and later to others was that she had somehow invented the magazine and Pat and I—and sometimes also Clay—had stolen it. Her mantra to me was “I can destroy you.” If she didn’t get enough credit or media attention, she would yell and throw things; I’d never experienced anyone like that before, and I kept trying to appease her. After we gave her all the money, she still sued us for fraud. [In 1975, Betty Harris sued Steinem and Carbine for $1.7 million, but the case was dismissed.]

Peacock: By the second issue, we had a stylish art director who’d come over from Harper’s Bazaar [Bea Feitler], and writers were dying to write for Ms. It was whizzing from then on.

Cathie Black (advertising director, 1972–77): I remember having lunch with Clay and saying, “I’m going to go to Ms.” He said, “I think this is going to be a big professional mistake.” And I told him, “I think it will be the best move I ever made.” I thought, I want to get on this boat. I don’t want to be left behind.

Edgar: A lot of people got hired just because they walked in the door.

Mary Thom (co-editor, 1972–91): It was like a political camp. It really was. People wandered in and took jobs.

Levine: I came in, and Gloria gave me the only chair, and she sat on the floor and offered to get me a cup of coffee. She didn’t know what to ask me because she didn’t know how to run a magazine.

Harriet Lyons (co-editor, 1972–80): I walked into Ms. early in March of ’72. The only phone that worked was adjacent to where the editorial meeting was taking place, so I was able to eavesdrop.

Levine: Somebody answering phones could come into the editorial meeting and say, “Wait a second, that’s not the way it is!”

Lyons: I recall hearing that the cover was set for the first issue after the preview: “Wonder Woman for President.” They were looking for a well-known woman with a feminist component [for the cover of the subsequent issue]. I just peeked out of my corner and spontaneously said, “The tenth anniversary of Monroe’s death is coming up.” And it seemed to strike a chord. That was my very first day. After the meeting was over, Gloria approached me and said, “What are you doing with the rest of your life?” And I joked, “Make me an offer.”

Getting Ads

(or not getting ads)

Steinem (in her 1983 book Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions): “Trying to start a magazine controlled editorially and financially by its female staff in a world accustomed to the authority of men and investors should be the subject of a musical comedy.”

Peacock: Gloria and Pat would go out and do the dog-and-pony show to get ads to support us.

Steinem: That was the worst. We were met with pure, unadulterated hostility.

Black: We were dropped off the high dive into the pool.

Peacock: Gloria, Pat, and their team would go to Detroit, and the car companies would say, “Oh, now, women don’t buy cars,” and the Ms. team would pull out their research and say, “Yes, actually they do,” but the car executives would still dodge and weave and ultimately turn them down.

Black: I had an ad-agency guy grab our research report out of my hands, throw it on the floor, and make a gesture as though he were going to spit on it.

Carbine: I think people accepted meetings with us because, if all else failed, it would be nice to meet Gloria Steinem.

Steinem: They were just curious about me—you know, “It walks! It talks!” The good news was that we became the only ad-presentation meeting at agencies that the secretaries came to.

Carbine: They often were a big help in getting us the appointment in the first place.

Steinem: Advertisers like Whirlpool sent us issues of Ms. with every sexual word underlined in a yellow marker, to show why they wouldn’t advertise.

Carbine: When Ms. published our groundbreaking article on female-genital mutilation, the ad director of Working Woman magazine sent a directive to her advertising staff telling them to use it against us.

Steinem: They sold against us by saying we were the magazine of hairy arm-pitted, black, lesbian farmworkers.

Stan Pottinger (Steinem’s then-boyfriend, former assistant attorney general for presidents Nixon and Ford): Gloria and I were both in Los Angeles, and Gloria asked me to drop by a restaurant to join her and Pat while they pitched someone from the California Avocado Growers’ Association. Gloria gave me a tip before I showed up, saying that the avocado association was a tough sell because they thought Ms. was “lesbian” and sexually explicit. Gloria thought that if her real-life boyfriend showed up, it might take the edge off the homophobia thing.

The conversation got ugly pretty fast. The more Mr. Avocado drank, the more out of control he got. “Why the hell would I want to put an ad in a magazine for lesbians?” he said. “This magazine is garbage. You’re going to tell men to put avocados on their penises.” No kidding. I’ve been in some pretty bad meetings, but this one was about as bad as it gets. It was impressive that Gloria stayed in the ring for as long as she did. I don’t know many people who would have. But a few months later she said, “Guess what? The California avocado association bought an ad.”

Black: Oh my God, we would celebrate the breakthroughs. Volkswagen came in. Oldsmobile. But most of the time, people were pretty discouraged. It was hard to get up and pound the pavement every day.

Steinem: You know, I have made lots of mistakes all on my own, and I have done all kinds of things that I would like to change, but most of all, I would like to take back all the time I spent trying to sell advertising.

Packaging Versus Politics:

The Debate Over Ms. Covers

Peacock: Those of us who wanted better cover images and better cover lines got resistance from people for whom ideology ruled everything. They didn’t seem to understand what the medium was. The idea was to entice people to read the magazine.

Carbine: If we had not made the magazine appealing to a wide-enough audience, it would have been, as Gloria always said, “like preparing for an absolutely great party and not sending out any invitations.”

Lyons: We called it “sugarcoating the pill.”

Pogrebin: When we put a woman on the cover—a real person—she had to be a worthy real person, not a Hollywood beauty. We had Helen Gahagan Douglas [congresswoman, 1945–51], Shirley Chisholm [first black woman in Congress], Bella Abzug [congresswoman, 1971–77]. These were our cover girls.

Robin Morgan (editor/contributor, 1977–present): We had a debate over the sexual-harassment cover [November 1977], where we didn’t want to actually show it happening in a photograph.

Edgar: We used dolls, showing a man putting his hand down a woman’s shirt at work. I also remember the battered-women cover [August 1976], when we showed a woman with a bruised face, and the sex issue [November 76], when we ended up, after much discussion, with a text cover: “How’s Your Sex Life?” And three boxes: “Better, Worse, I Forget.”

Lyons: The most agonizing cover debate [April 1975] was over Warhol superstar Viva (we had a story about her still breast-feeding her 5-year-old daughter) versus the suspicious death of Karen Silkwood [union activist at a chemical plant]. We had an exclusive with Silkwood’s family. But it came down to the art: a crumpled car versus gorgeous Viva with hair flowing to the heavens. Viva won. Of course, we all regretted it.

Morgan: The ad department always wanted Gloria on the cover, and poor Gloria always fought that … But those covers sold well, so sometimes she lost.

Lyons: When you look at the best-selling issues, the men’s issue [October 1975] stands out; it flew off the newsstands because we had Robert Redford’s back with a copy of Ms. magazine in his jeans pocket with his perfect butt.

Braudy: I was always a little bit of the outsider—not part of this tight “in” group of Gloria, Letty, Mary Thom, and Robin Morgan. I wanted to put Robert Redford on the cover of the men’s issue, and Gloria said, “No, we can’t do that.” So she takes a vote, and the staff voted to put just his back on the cover. Such a stupid idea.

New York Magazine, September 22, 1975

“Guess Whose Back”

“Who’s that beefy hunk of fascinating manhood on Ms. Magazine’s October cover?”

Lippert: We leaked to Liz Smith for her column that it was actually Redford’s butt. The issue got attention.

Braudy: This is one of my quarrels with the Ms. people: They never told me that it was one of the highest-selling issues in the magazine’s history. They never told me it was a success.

Lyons: Susan Braudy also argued that Warren Beatty should be the cover subject for our issue on the Equal Rights Amendment because he was pro-ERA. But at the time, he was the ultimate womanizer, and she was booed off the stage.

Braudy: Gloria hated it. She said she’d had dinner with Beatty in London, and he got down on all fours and looked under the tablecloth to see her legs. She was wearing a high miniskirt, and you know, she had these perfect legs. She said to me, “Okay, look, let’s just see if Warren Beatty will do it first.”

Steinem: I don’t remember it—either Beatty being on the cover or under a tablecloth. I would have been grateful for Beatty’s support for the ERA.

Braudy: I had the task of calling Warren Beatty and asking him for a time to talk, and he proposed lunch at the Palm Restaurant. It’s a very old-school, male place. I ordered a Caesar salad, and he ordered a huge steak and said to me, “Have a piece of steak.” I said, “No, thank you,” and he pushed the plate at me hard. We pushed it back and forth about fifteen times until we laughed and then I stopped being afraid of him. Anyway, he agreed and said he would do the cover. I said to Gloria, “This will be great.” But she finally said no, and I was left holding the bag.

Intra-Feminist Discord

Ellen Willis’s Resignation Letter, 1975 (contributor, 1973–75; co-founder of the Redstockings, a radical feminist group; died in 2006.)

“No attempt has ever been made to recruit and hire experienced feminist writers, theorists, organizers … Ms.’s politics [include] a mushy, sentimental idea of sisterhood designed to obscure political conflicts between women … I hope that this explanation will be received as the honest feminist criticism it is meant to be.”

Carbine: Compared to every other magazine being published primarily for women, Ms. was—and was thought to be—wildly radical. But that didn’t help us with our downtown friends.

Gornick: People in Redstockings started calling Gloria and Ms. enemies of the movement because the “message,” from the radicals’ point of view (and here I include myself), was too watered down. But I hated the Steinem-bashing. I wrote a piece to say, “If you don’t like Ms., start a magazine of your own.”

Morgan: Some of the carping from self-described radicals was plain crankiness at not running things, or resentment at feeling not included (despite repeated invitations), or jealousy when Ms. succeeded beyond expectations.

In 1975, the reconstituted Redstockings accused Steinem and Ms. of being part of a CIA plot to collect information on the women’s movement. Steinem refused at first to dignify the charges with a response, and Betty Friedan, feminist pioneer and author of The Feminine Mystique, seized on her silence.

The New York Times, August 29, 1975

“Dissension Among Feminists: The Rift Widens,”

By Betty Friedan

“By dismissing the Redstockings’ charges as ‘McCarthyism,’ I don’t think she shows respect for the women’s movement.”

Braudy: Betty Friedan was jealous of Gloria and claimed (with some justification) that because Gloria was younger and beautiful, the media anointed her spokesperson. That said, when I was trailing after Betty for a piece for Playboy, I was appalled by her loud vocal disdain for some women. For example, she cruelly berated an older woman selling train tickets at Philly’s Penn Station for being too slow. In a hundred years, Gloria would never do such a thing.

Ephron in Crazy Salad, 1975

“It is probably too easy to go on about the two of them this way: Betty as the Wicked Witch of the West, Gloria as Ozma, Glinda, Dorothy—take your pick … Betty Friedan, in her thoroughly irrational hatred of Steinem, has ceased caring whether or not the effects of that hatred are good or bad for the women’s movement.”

Steinem: I couldn’t look into Betty Friedan’s head and heart, but she was hostile not just to me but to Bella [Abzug] and pretty much anyone who challenged her ownership of the women’s movement.

Thom: I think we at Ms. found it hard to be critical of the women’s movement. The first time we decided to treat controversy as controversy was when we did the piece that explored how one woman’s pornography is another woman’s eroticism [April 1985].

Levine: That debate was intense. And some people never got over it.

Mary Kay Blakely (contributor, 1982–2002): Even debates among editors who were close friends became defensive, judgmental, and hostile. You were either a vanilla-sex feminist or a bad-ass feminist.

Pogrebin: I threatened to leave over a manuscript by a woman who was a former editor of ours who was writing about why she was a masochist and trying to make it an okay choice. I would rather leave than work for a magazine that published that. And we didn’t publish it.

Ruth Sullivan (co-editor, 1972–85): Alice Walker was very much for publishing it. I remember she quoted Tennessee Williams in her editorial comment on the story: “Nothing human disgusts me.”

Alice Walker (contributor, 1974–86): I don’t recall this at all! Me, quoting Tennessee Williams?

Braudy: I argued for a brilliant short story by Harold Brodkey to be included in the men’s issue. It was partly about this Harvard student performing oral sex on his true love, this Radcliffe beauty … I said, “I want to put this in as an example of this emotional and intelligent rumination of a man.”

Levine: I thought it was a horrible piece.

Sullivan: At one editorial meeting, Pat Carbine announced that Ms. was going to be recorded for the blind. I said I felt sorry for the poor reader who had to read the Brodkey story. Can you imagine the long pauses and the “oooooohhhs” and “ah, ah, aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhs”?

Lyons: There were staff, readers, and critics who would complain that Ms.’s coverage of lesbian issues was lacking.

Lindsy Van Gelder (contributor, 1977–92): Anything that equated feminism with lesbianism lost Ms. potential advertisers, and the first article in which I came out [February, 1984] was radical even by the lesbian standards of the day. It was called “Marriage As a Restricted Club,” and it was about my decision not to attend weddings of straight friends and family members. It was also a plea for straight feminists to understand that they had rights I didn’t.

Steinem: It was always clear to me that feminists were going to be called lesbians … so the only answer was to make clear that being a lesbian was as honorable as any other way of living. When people on the road asked in a hostile way if I was a lesbian, I always said, “Not yet.”

Lyons: Ms. was perceived as middle class and elitist. Perhaps an editorial staff comprised of mainly white, Ivy League–sister-school alumna can’t overcome that perception. But the content speaks for itself.

Edgar: Some women said they did not see themselves enough in Ms.

Alice Walker’s Resignation Letter, 1986

“I am writing to let you know of the swift alienation from the magazine my daughter and I feel each time it arrives with its determinedly (and to us grim) white cover … It was nice to be a Ms. cover myself once. But a people of color cover once or twice a year is not enough. In real life, people of color occur with much more frequency. I do not feel welcome in the world you are projecting.”

Walker: The proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back was a Ms. cover showing two pregnant women, both white. This would have been such an easy cover on which to show a bit of diversity.

Marcia Ann Gillespie (editor/contributor, 1981—2001): After Alice resigned, I asked myself if I wanted to be associated with the magazine. I decided to move forward with Ms. because I felt there was a need to keep pressing from within.

Sullivan: I think Alice felt the burden of being, as she described it, the token black woman at Ms. Even though this was literally not the case. But when she worked in the office, it fell on her to generate the articles dealing with women of color.

Van Gelder: I was present at at least one editorial meeting where the editors openly talked about their belief that putting black people on the cover would depress newsstand sales.

Carbine: When we wanted our piece on Alice Walker to have the importance of a cover story, we knew we were endangering our newsstand distribution in the South. Sure enough, Ms. distribution was curtailed, and our distribution company was very unhappy with me.

The Legacy

In the late eighties and throughout the nineties, Ms.’s popularity waned as women’s legal and professional statuses improved and a crop of new magazines were launched, often co-opting Ms.’s message and readership. In a 1990 Mother Jones cover story, Ms. Fights for Its Life,” Peggy Orenstein wrote, “Magazines such as Working Woman, Savvy, New York Woman, and Mirabella may have poached some of the Ms. terrain, but they’ve manipulated the message, reflecting change but not inciting it.” And for many women, the word feminist became freighted with anti-male or militant-lesbian associations. “Those from journalistic backgrounds felt Ms. was getting defensive in the eighties because the movement was under attack and had become too ideological, and there was some leave-taking,” says Lyons. As a result, the ads that were always hard-won for Ms. became even harder to get, circulation fluctuated, and the magazine switched owners six times in fourteen years. Today, Ms. is published by the Feminist Majority Foundation, headed by Eleanor Smeal, which bought the magazine in 2001 and puts out four issues a year. While the magazine has developed a strong presence on the web and its archives are used widely in college curricula, Ms. never reclaimed the full cultural influence of those early years.

Gillespie: The magazine, despite its flaws, provided so many words that had been missing. So many silences finally broken. Ms. changed lives, changed attitudes, helped to create and change laws, policies, practices.

Bernikow: The power of Ms. was its ability to provide a language for people outside New York City or California, who never would have otherwise penetrated the right-wing wall that said feminism was nuts, man-eating.

Morgan: Family secrets spilled out, abusive homes and relationships were exposed, “It’s always been that way” customs and prejudices were shown up.

Black: Those of us who were there were on a mission.

Rita Waterman (production, 1972–79): For me, the burden of Ms. was that I had to get it right. Failure or letting people down was personally and professionally unacceptable.

Edgar: If I had known how big it was, I would have taken more notes and kept a diary.

Morgan: It couldn’t have been done without Gloria. It was her baby. Her own writing career has suffered, her books have suffered. It completely took her over.

Steinem: I confess that there were moments when I realized that I was fantasizing that the magazine would burn down. And I thought, “Why am I dreaming of this over and over?” And then I realized that if it burned down, I would be free, and no one would be mad at me because it wasn’t my fault. There were those times.

Edgar: She was always reluctant to take what she called an “office job,” and this was her first.

Steinem: I just remember saying to Clay, “I’m only doing this for two years.”

Carbine: I knew that I was electing the road that would, I hope, be a small contribution to helping make this change happen for women and therefore for men. I wanted the world to be different. I knew what my trade-offs were when I committed my life to Ms., that I became even less marriageable and would grow old as a single woman.

Morgan: Men are better at celebrating successes. They have parades and trophies. But there was a transformation in those early Ms. years—in terms of family structures, the workplace, and our language. It would still be decades before the New York Times would come onboard to use the term “Ms.” [It was in 1986.]

Bernikow: I still meet women who say they had to hide their Ms. magazines from their husbands. It woke women up and spurred them to go out and do something.

Levine: I can’t understand where we got the chutzpah to turn people’s lives upside down.

Susan Brownmiller (author of Against Our Will): I’ll say that for me, Ms. never had anything that was a revelation. We radical feminists, we were raising new issues first, and then they would get to Ms.—eventually, but not initially.

Gornick: I don’t think it did a damn thing forfeminism.

Steinem: I can understand if longtime feminists wanted more. But there needed to be articles that were for readers picking up a feminist magazine for the first or fifth or the tenth time.

Pogrebin: We consciously tried to recognize and publish for the entire spectrum.

Steinem: If you’d asked me in the beginning how long it would last, out of both pessimism and optimism, I would have probably said, “Three or four years, tops.”

Braudy: The lessons that were imprinted on me are like religious beliefs.

Brownmiller: Women of course don’t know the history and tend to think of feminists as funny old people.

Blakely: It’s hard for my journalism students today to even imagine what the culture was like before Ms. raised public consciousness.

Steinem: I’m not at all sure that I understood it at the time because I was so conscious of what there was to do and what we had to leave out. But today I reread the first issue and said, “This was really good.”

See Also:

• Read the Preview Issue of Ms.

• Emily Nussbaum on the Rise of the Feminist Blogosphere