Leonardo da Vinci famously said, “An artist’s studio should be a small space because small rooms discipline the mind and large ones distract it,” referring perhaps to a modest studiolo where one might work on preparatory drawings of Isabella d’Este or put the finishing touches on the Mona Lisa. On the other hand, working in a small space on a large work—let’s say The Annunciation—is potentially more distracting and highly unlikely to inspire discipline in any but the most receptive mind.

It’s an unfortunate reality for many artists—particularly in New York City—where square footage is at a premium and so many of those airy industrial lofts that once accommodated the quirks of the creative class have been converted into expansive, and expensive, luxury condos. Once-gritty Great Jones Street, where Basquiat painted in a building owned by Warhol, is now a genteel neighborhood of five-figure rents. Zero Bond is just around the corner, no doubt capitalizing to some extent on the cultural cachet of the area.

Artists do have the option of decamping for lower-cost-of-living locales, which ironically is how so many ended up in the Big Apple in the first place. The stereotypical high-ceilinged warehouse and factory lofts of SoHo that so many people associate with artists were such a draw specifically because they were, in the 1960s through the 1980s, so cheap, while the arts, thanks to organizations like the National Endowment of the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts, were funded so well. Fast forward several decades and, in Manhattan in particular, average rents, which weren’t cheap before, have risen 15 percent post-Covid, with Brooklyn and Queens not far behind, which means decamping for more affordable pastures requires going very far indeed.

That’s a problem for several reasons. Lower Manhattan may no longer be the nucleus of the cultural universe the way it was when Basquiat, Donald Judd, Nam June Paik, Chuck Close, Ray Parker, Eva Hesse and others were creating art there—and there’s no denying the internet has lessened the importance of geography in the visual arts to some degree—but if you want to be discovered, if you want to be seen and if you want to advance in your career in the art world, New York is still the place to be.

One solution that’s floated in discussions centered on urban artists across the nation is the construction of government-sponsored live/work spaces specifically for creatives. Former mayor Bill de Blasio’s contentious Housing New York plan included the construction of “1,500 units of live/work housing for the artists and musicians who make New York culture so vibrant.” That sounds like a lot until you consider that as pricey as the city is, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs estimates that more than 100,000 artists live/work here. Fifteen hundred units won’t do much to take the pressure off, and that’s assuming creatives want to work where they live. Gentrification, aka the SoHo Effect, can be a thorny issue, as are some of the rules surrounding zoning certification (notably around who qualifies as an artist), and many artists—particularly painters of mammoth canvases and sculptors and installation artists—need more square footage than affordable housing designated for artists can reasonably offer.

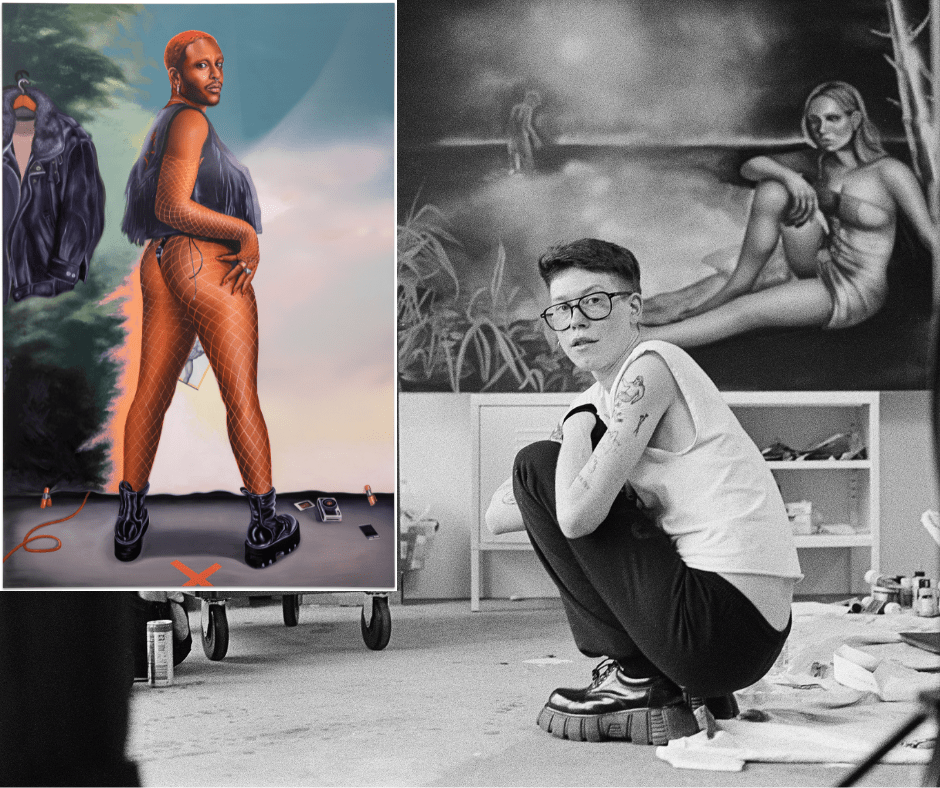

“I can paint anywhere on a small scale, but a lot of my paintings are larger and when I work with other people, I need space,” says New York painter Alannah Farrell, whose body of work includes both self-portraiture and thoughtfully rendered depictions of the people they’ve met through Queer New York City nightlife.

Making space for artists in Downtown Manhattan

In what feels like a nod to New York art history, commercial real estate, not residential real estate, may hold the key to keeping artists in the city—and in particular, Manhattan. Why? Because the median rent for a Manhattan apartment was more than $4,300 in January of 2024, more than twice the national average. Or because as much as we like to equate ‘artist’ with ‘painter,’ plenty of people in the creative classes are welding, carving wood, shaping polymers and otherwise working with or on stuff that’s not exactly residential real estate friendly. And finally, because as much as artists need somewhere to lay their heads at night, they also need workspaces that are centrally located and easily accessible to the people who can buy their work.

“If you have a studio somewhere outside of Manhattan, like in Bridgewood or deep in Bushwick or Queens or New Jersey, it’s harder to get collectors and gallerists and art dealers and museums to come see your work,” Gregory Alan Thornbury, executive director of Silver Art Projects, tells Observer. “If you want to be discovered, if you want to be seen, if you want to advance in your career in the art world, you have to be in New York.”

Silver Art Projects was founded in 2018 by Cory Silverstein, grandson of real estate entrepreneur and public art supporter Larry Silverstein, and Joshua Pulman to provide artists with critically needed New York City studio space. It takes up the entirety of the 28th floor of Four World Trade Center, the use of which was generously donated in perpetuity to the organization by Silverstein Properties.

Painter Yuri Yuan, whose work walks a fine line between representation and abstraction and is one of the resident artists currently working in that space, echoed Thornbury’s sentiment: “The art market is very slow right now, so it’s nice to have a free studio space. My last studio was in Jersey City, and I was feeling a little bit secluded out there. A lot of people don’t want to travel all that way for studio visits. It’s not that far from New York, but it’s definitely not as easy to get to as the World Trade Center.”

As to what working in the space is like, imagine 44,000 square feet of bright, open space lined all the way around with tall windows overlooking the busy streets of Lower Manhattan and the rivers beyond. Large dividers on wheels split the open floor into twenty-eight studios ranging in size from 500 square feet to 1,200 square feet along with a common area and administrative space, that accommodate an annual cohort of artists-in-residence that this year includes Farrell and Yuan, Anastasia Komar, Anastasiya Tarasenko, Azadeh Nia, Daniel Um, Diana Sinclair, Eli Hill, Gwen Hollingsworth, Haley Mellin, Jaymerson Payton, Jean-Pierre Villafañe, Kwesi O. Kwarteng, Kyung-Me, Lily Wong, Malaika Temba, Raul De Lara, Rowan Renee, Sherrill Roland, Will Maxen, Xi Li and Yuan Fang, plus returning fellows Helina Metaferia, Jared Owens, Russell Craig and Sagarika Sundaram.

How they, and the cohorts that preceded them—a group that includes artists like Tourmaline, who was included in this year’s Whitney Biennial—is a story spanning decades.

The artists in the WTC

The genesis of Silver Art Projects can be traced back to the 1980s when Larry Silverstein built the first 7 World Trade Center. According to the lore, as recounted by Silverstein Properties CMO Dara McQuillan, the senior Silverstein had around that time fallen in love with Carmen Red granite, and “it was on the outside and on the inside—he put it everywhere.” But on the day he opened the building, Silverstein walked into the three-story high lobby and thought it looked like nothing so much as a mausoleum. He called his wife, Klara Silverstein, to come down and tell him if he was crazy or not, and when she saw it, she said, ‘Yeah, that’s pretty much it.’ The couple would spend the next decade buying art that changed the look and feel of 7WTC for the better.

They started with these massive Frank Stella pieces,” McQuillan tells Observer. “They borrowed this Calder from the Port Authority and put it right in front of the building. Over the years, they breathed life into it with these very beautiful and very large pieces of art, really transforming it.”

All of it was lost in the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, part of the estimated $110 million of private and public art destroyed on that day that included works by Al Held (The Third Circle, 1986), Roy Lichtenstein (Entablature, 1975) and Frank Stella (Laestrygonia I and Telepilus Laestrygonia II). Larry Silverstein, despite facing a host of not insubstantial challenges, was committed to rebuilding and, according to McQuillan, wanted artists to be a part of the process from day one. Seven World Trade Center, the first building to be rebuilt, was designed by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, but Jenny Holzer collaborated on the design and created a large installation for the lobby: a 65-foot-wide, 14-foot-high scrolling selection of New York-focused prose and poetry that hides a fortified-glass security shield. Light artist James Carpenter designed the entire base of the building with Childs.

A currently unleased floor of 7WTC has facsimiles of some of the pieces that the Silversteins purchased or commissioned and then lost, along with an emotional timeline of the post-9/11 rebuilding process as told through the work of the Larry Silverstein artists invited in to document it. Among them is Jacqueline Gourevitch, a former resident artist in the original Twin Towers who specializes in painting the city from above.

“As we were rebuilding, we connected with Gourevitch and invited her to come and literally paint everything she saw out the window starting in 2008, and she’s still here, painting on the top floor of Three World Trade Center,” McQuillan says. “She has this incredible body of work that speaks to everything that we did to get this place built.

Todd Stone, another of the trade center’s long-time artists in residence, painted the site before, during and after the attacks, creating a “painted documentary” that’s like a beautiful time-lapse of the massive transformation of Ground Zero and was exhibited at the NYC Culture Club Gallery in the Oculus on the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. “At some point, he came to us and said, ‘Hey listen, I’ve had a lot of fun painting your building from the outside. Do you think I could come inside and check out the views?” McQuillan recalled. “We were like, are you kidding me, yes!”

More artists followed. Silverstein Properties didn’t have the marketing budget to pay for it, but it did have a lot of space to give and wasn’t asking artists for a stake in their work. “The deal was pretty simple. You come in whenever you want. You can use our space. You can paint whatever you want. Whatever you create is all yours. You can show it, sell it, create books out of it, whatever. What we got out of it was these different storytellers documenting our project in different ways.”

Viewed collectively, that work is a visual archive of how downtown Manhattan has been reshaped over the past two decades. It’s also a project without end. There are still resident artists working in Larry Silverstein’s properties, like abstract impressionist Kerry Irvine who also paints on the top floor of Three World Trade Center. Then there are the artists who work in the space temporarily and then move on, sometimes leaving their mark: Hugo Bastidas, Kamika Patton, Cristina Martinez and many others.

“What started with Larry and Klara learning about and appreciating the importance of public art evolved into the World Trade Center being a place where artists can find space, feel at home and be inspired,” McQuillan says. “But all of this over the years has been a little bit haphazard and a little random. Here, it unfolded organically and almost by accident. What Gregory has done with Cory and Joshua is formalize the whole thing, creating a structure around what we were doing, and it’s terrific.”

Artists need more than studios

What that structure looks like in practice has less to do with giving artists space to work than with rebuilding the connected ecosystem that allowed artists working downtown to influence the culture of New York City once upon a time. The way Thornbury tells it, Cory Silverstein (who was working in private equity in the real estate world but had studied art history at Columbia) initially approached his grandfather and said something to the effect of ‘Real estate developers have this reputation of developing amazing properties and neighborhoods and then pricing the artists out—what if we brought them back?’ But he, with Thornbury and program director Lilly Robicsek, ended up doing a lot more than that because the artists who set up shop on the 28th floor of Four World Trade Center each year do more than work.

They also meet top gallerists, collectors, museum leaders and artists who come to Silver Art to tour the studios and, depending on the visitor, to trend hunt or acquire art or mentor fellow creatives. Last year, MoMA director Glenn D. Lowry did a studio visit with every single one of the resident artists—a privilege relatively few artists will ever enjoy and one that was coordinated by Thornbury and his team. Russel Craig, a second-year Silver Art Projects senior fellow and co-founder of Right of Return USA which became the artist-led Center for Art & Advocacy, spoke of meeting collectors and celebrities: “You never know who’s going to be coming through—there are some heavy hitters.”

Robicsek speaks with great enthusiasm about what the artists in the program go on to achieve, which, if past cohorts are any indication, can include presenting in solo and group shows at galleries and museums, being chosen for prestigious awards and grants and attracting collector and museum attention. “Every single artist who has gone through this program has left with the wind at their back,” Thornbury says. “It’s an accelerator. I call it the Y Combinator of the arts because all of the artists, whether emerging or already somewhat established, go on to do incredible things.”

Making connections in the art world is all about planting seeds, according to Yuan. “You plant a seed and after a few years, that connection pays off. I have a show in New York next spring, and I’ll be able to reach out to all of these people who’ve been to my studio here and seen my work to invite them to that show.”

Another facet of Silver Art Projects’s mission is, according to the organization’s website, “changing the very nature of who has these opportunities and outcomes.” Given the enormous impact they hoped to have on artists’ careers, Silverstein and Pulman opted to reserve four spots in each cohort specifically for justice-impacted artists, of which Craig is one (his work was in “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration” at MoMA PS1), and to actively support artists from marginalized communities—“specifically artists in the LGBTQ, Black, Asian communities and artists with disabilities,” the duo wrote in a 2022 op-ed.

Part of that involves putting together diverse selection committees that ensure a diversity of artists are represented in each cohort. The most recent included artist Derek Fordjour, artist Marilyn Minter, Art Intelligence Global co-founder Yuki Terase, Kickstarter CEO Everette Taylor, former Whitney curator and chief artistic director of art nonprofit Horizon Christopher Y. Lew, Financial Times editor Enuma Okoro, Gagosian liaison and mega-collector Sophia Cohen, arts supporter and podcaster Phyllis Hollis and Venus Williams. Together, they built a cohort that by all accounts is not only talented and diverse but also just very cool to be around—the artists I talked to for this article spoke about getting feedback from fellow residents, bouncing ideas off each other and having stimulating conversations, with the caveat that everyone is respectful of the fact that they’re there to work.

In that regard, Farrell plans to do as much work as they can and have as many people come in to sit as time allows, but they’re not spending too much time thinking about what’s ahead. “I’m ambitious and career-focused, but I’m not necessarily a game plan person per se because I know life can throw whatever at you whenever,” they say. “It’s really just amazing to have this space and this light in Manhattan and to be able to walk here, and I’m not thinking about the end of the program—I just want to savor every moment.”

Cities need artists as much as artists need cities

The question, of course, is whether and how the Silver Art Projects model can be scaled. That could involve scaling up where partnerships and exposure are concerned, perhaps by bringing in more museum professionals, gallerists, collectors and art world insiders to interface with the resident artists or finding innovative ways to increase the reach of the organization’s impact by building relationships with allies equally committed to keeping artists in New York City. NYU’s Gallatin School, which bills itself as a ‘university without walls,’ might seem like an unlikely collaborator, but there’s already a Gallatin faculty member in residence at Silver Art—Ernest Bryant—who is both doing his own work there and teaching a course on literary and art criticism in the space.

“It’s about having proximity with working artists and being inspired by their work and seeing their work as not just as published in a textbook or hanging in a museum, but actually in process,” says Victoria Rosner, Dean of the Gallatin School. “Then they’re speaking to the artists and asking questions: Tell me about your practice. How did you choose these materials? How did you choose these themes? How did you choose these methods of execution?”

Rosner believes the potential for collaboration is limitless and sees collaborative events as being the next frontier in the evolving partnership that could involve not just students but also alumni and faculty. “It feels like such a space of possibility. As someone who grew up in New York and thinks of New York, including Manhattan, as a place for artists, it’s just wonderful to be in the presence of and a part of this burgeoning artistic community.”

Scalability here could also mean replicability. What the long-term outlook for traditional commercial real estate in a post-Covid, work-from-home-friendly world looks like is anyone’s guess but right now, millions of square feet of urban office spaces sit empty. Downtown Manhattan’s vacancy rate was closing in on 23 percent this past April, according to research by commercial real estate services and investment company CBRE, which means that technically, there’s plenty of space in New York City and in other major metro areas around the U.S. for artists. The biggest hurdle will be getting more real estate development, investment and management firms to embrace the Silverstein Properties/Silver Art Projects model of supporting the arts with space.

Those who balk at the idea of the lost revenue—which for a full floor of a New York City high-rise adds up to millions annually—might want to reconsider. Decades of studies show that empowering artists to stay local is good for cities. “Wherever they are, business and commerce follow,” says Thornbury. “They’re at the vanguard of making a place feel culturally relevant.”

Of course, whether artists stay in a city isn’t just about the availability of studio space. Affordability, accessibility, diversity, inequality and the social determinants of health can all impact the flow of artists into and out of urban areas. But creating spaces where artists can work—big, bright, welcoming, inspiring and collaborative spaces like those on the 28th floor of Four World Trade Center—is a good place to start.

“Sometimes when I’m stressed, I’ll just take a moment to look out the window,” muses Craig, who used to work in the Brooklyn Army Terminal. “I remember on September 11, I watched it happen on TV and it felt unreal, so it’s a crazy feeling to look out my studio window and see the memorial right outside. I never imagined that years later, I’d be in the World Trade Center working, so I try to be respectful of that and really take full advantage of the opportunity. The longer I’m here, the more I realize there is so much more to this.”