When Shakil Khatri first heard about Amazon Karigar in 2018, he thought it might be what he had been looking for. Khatri, a sixth-generation artisan, is one of the few remaining batik craftspeople in western India’s handicraft-rich Kutch district. In recent years, fewer people have visited his workshop to buy his hand-dyed sarees and dupattas, prompting him to expand the business to e-commerce sites like Itokri and GoCoop. Amazon Karigar, he thought, could help him reach a larger base of new, non-local customers.

The program solicited Indian artisans to sell their wares through Amazon’s e-commerce platform by offering nine weeks of training, professional product photos, and marketing. It had launched a year earlier with 55,000 products on the site, including hand-loomed sarees, blue pottery from Jaipur, and other “Made in India” handicrafts.

Khatri registered for the program and gave samples of his products to an Amazon representative, who had them photographed and listed on the platform. Two months later, not a single item had sold. Khatri decided to pull his products off the site.

Amazon promotes its Karigar program with a biannual special sale event and partnerships with crafts cooperatives and nonprofits from several Indian states. “These efforts not only help artisans grow their businesses but also engage them in the digital economy, preserving India’s rich cultural heritage,” an Amazon India spokesperson told Rest of World.

Khatri said that Amazon failed to understand how to represent and promote his work. Several other artisans and organizations in Kutch who worked with Amazon told Rest of World that the program did not help them find any customers.

Harsh Dave, co-founder of Kutch Ji Chapp, a handicrafts manufacturer in Kutch, said Amazon got in touch with him in 2020. He spent a lot of time preparing his products for the platform, but did not sell any.

“They asked for photos — four different angles — and we sent them a lot of photos,” he said. “We sent sarees, fabrics, and dupattas. Around 40 to 50 products in total … We had 50 meters of each design, but we didn’t sell even one meter.”

Rest of World found only about a dozen artisans in Kutch who actively sell on Amazon Karigar, out of an estimated 6,000 from the region. Amazon did not provide the number of artisans in Kutch selling on its platform.

“The biggest flaw in the e-commerce marketplace model for handicrafts is that it treats these unique, often culturally significant items like any other mass-produced product,” Satish Reddy, a crafts mentor who works with artisans in Kutch, told Rest of World.

“We had 50 meters of each design, but we didn’t sell even one meter.”

“Artisans can’t sustain this model long-term. They need platforms that understand the intricacies of their work and offer real support in selling, rather than just listing their products,” he said.

Laila Tyabji, a social worker and the founder of Dastkar, an NGO that works with Indian craftspeople, told Rest of World that the “emphasis on identical products means that the rejection rate and returns is also huge. Nor is there a comprehension that a handcrafted product needs specialized, careful packaging, which craftspeople do not always have the facilities for, and which further eats into their profit margins.”

Khatri pointed to his experience with the India-based e-commerce platform Itokri. The company had given him the freedom to make textiles in any color or style, he told Rest of World, and they bought his products upfront. Amazon Karigar, on the other hand, merely listed his items, leaving him waiting for sales.

India’s handicraft industry is one of the biggest in the world. There are 200 million artisans in the country, estimates Ashoke Chatterjee, honorary president of the Crafts Council of India. Last year, the country’s handicraft exports amounted to $3.6 billion, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation, a trust established by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

For e-commerce sites, India’s artisans represent a massive opportunity. Both Amazon and the Walmart-owned Flipkart are racing to get local crafts vendors onto their platforms. Amazon Karigar now has 1.6 million vendors, the Amazon India spokesperson told Rest of World. Flipkart’s Samarth program had drawn 1.5 million vendors in 2023.

Paresh Mangalia, deputy director at Khamir, a nonprofit that works with Kutchi artisans, remembers when several artisans joined Amazon Karigar after its launch in 2017. The start was promising, but problems arose quickly, he told Rest of World.

One significant issue was stock management. Artisans in Kutch traditionally work on a made-to-order basis, crafting each piece one at a time. Most do not have the capacity to keep large inventories.

“They were used to a system where they would show their product to someone, take an order, and then make the item,” Mangalia said. “Many artisans didn’t have enough products to stock and sell immediately. So when orders came in, and they didn’t have the product on hand, it caused delays.”

Mangalia said that when artisans received walk-in customers, not enough stock would be left to fulfill Amazon’s orders. Sometimes there were delays with payment, fueling mistrust among the vendors.

Artisans didn’t like Amazon’s warehousing system, either. The company charged rent for storage space, and when a product was sold, Amazon deducted a warehousing fee from the sale. Few vendors opted to use the service.

“Through the Karigar program, Amazon has established clear payment processes that are prioritized timely, giving artisans assurance in their financial transactions,” the Amazon India spokesperson told Rest of World.

“Amazon made me their poster boy.”

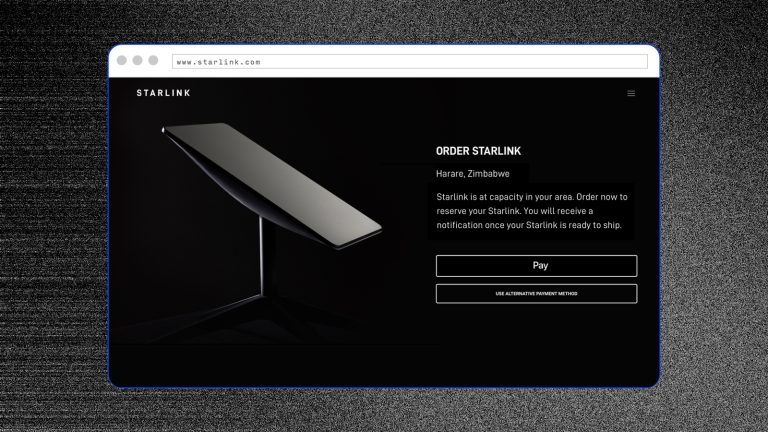

Photography, a critical part of selling products online, is another source of frustration for artisans.

Khatri told Rest of World he was not happy with the way his products were photographed because some details were left out and the photos did not accurately show the products’ size.

“The proportion of a dupatta in the photo of a model wearing it looks much bigger than it actually is,” Khatri said. “It’s a stole, just 20 inches. Now if a customer looks at this and buys the product, they will say you’ve only sent half of the product.”

He also said that Amazon customers who expect cheap prices don’t appreciate the quality of his products. While industrially produced batik is available at low prices, Khatri uses natural dyes and intricate traditional techniques.

“The public that buys cheap will not like costly handmade products like ours,” he said.

“Amazon was inherently geared towards industrial production; they weren’t looking at something curated,” said Reddy. The marketplace model doesn’t suit small-scale artisans who live hand-to-mouth, he said. Many of the artisans in Kutch can’t afford to produce large stocks of products, and then wait six months or more to make a sale.

Maji Khan Mutwa, an artisan from the village of Siniyado in Kutch, is one of the few craftspersons who have found success with Amazon Karigar. Though Amazon had initially hesitated to bring him on board due to the fragility of his mud murals, Mutwa joined the program in 2017. For the first six months, he didn’t receive any orders.

After he brought up the issue at an Amazon training seminar he attended, representatives from the company decided to feature his work in national marketing campaigns.

“Amazon made me their poster boy,” Mutwa told Rest of World.

He took advantage of the visibility, creating accounts on YouTube and Instagram. He posts videos of himself making mud murals, promotes his projects in different cities, and advertises upcoming projects. Some of his Instagram reels have 2 million views.

Despite his success, Mutwa said he does not want to depend on Amazon Karigar. He plans to create his own e-commerce platform to support fellow artisans.

“If I rely solely on Amazon, that’s not possible,” he said. “Maybe I’ll get good sales. But I can’t add anything personal.”