Mandy Pan thought she couldn’t go wrong with her first major purchase out of university: a silver plug-in hybrid from China’s leading electric vehicle maker, BYDBYDBYD Auto is a Chinese carmaker that became the world’s leading EV manufacturer in 2023, competing with Tesla for market share and global attention.READ MORE. The compact sedan, called Qin Plus, was a popular choice for its affordability and low energy consumption. Pan, a 22-year-old from China’s eastern province of Zhejiang, asked her father for a down payment on a five-year loan to pay for the 94,800-yuan ($13,168) car.

But less than four months later, as Chinese EV makers fight a fierce price war, the cost of BYD’s Qin Plus model has dropped by 15,000 yuan ($2,084) — more than what Pan makes in three months at her entry-level job. She was also shocked by the high insurance premiums for plug-in hybrids, and the long charging times.

“I feel like I was scammed out of 15,000 yuan,” Pan told Rest of World, adding that she didn’t expect such a drastic price drop. “They should at least give us some compensation. I really regret getting this car.”

“I feel like I was scammed out of 15,000 yuan; they should at least give us some compensation.”

After years of rapid growth spurred by government support, the world’s biggest EV market is facing a slowdown as consumers cut spending in an uncertain post-pandemic economy. As carmakers slash prices further to sustain their sales, some car owners are seeing the value of their vehicles plummet months or even weeks after their purchases. Several EV companies are also in financial crises, leaving thousands of buyers unable to access after-sales and software maintenance services.

EV startups HiPhi, the Baidu-backed WM Motor, and the Tencent-backed Aiways have run out of funds to sustain their operations. Other brands including Levdeo and Singulato Motors have entered bankruptcy proceedings.

China’s EV industry is transitioning from a period of unbridled growth to consolidation, analysts told Rest of World. The annual sales of China’s new-energy cars, which include EVs and plug-in hybrids, are projected to grow 22% in 2024 to reach 11 million vehicles. That is slower than previous years: EV sales grew by 36% in 2023, when 7.7 million units were sold, and by 90% in 2022, with 5.7 million units sold. The government stopped offering purchase subsidies at the end of 2022, while some other EV support measures, such as tax incentives and favorable licensing plate policies, remain in place.

Carmakers are now aggressively cutting prices to fight for limited growth space. Since February, BYD — China’s top-selling brand that sold some 2.4 million cars in 2023 — has slashed the prices of almost all of its models. In February, it introduced a 79,800-yuan ($11,112) hybrid plug-in under the slogan, “Batteries are cheaper than engines.” More than 10 other EV brands fought back by lowering their own prices. Tesla also introduced fresh discounts and subsidies.

“The overlying sentiment of the Chinese economy is not good,” Tu Le, founder of Sino Auto Insights consultancy, told Rest of World. “There are still too many brands and still too many products.”

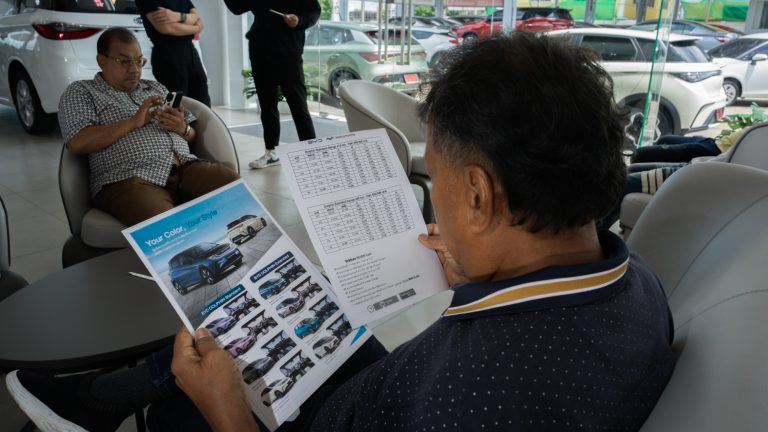

The frequent price cuts have frustrated EV owners, especially those who purchased cars recently. In February, car quality monitoring platform 12365auto.com said it received 6,884 complaints over price changes, mostly targeting domestic EV brands — accounting for 45% of all auto-related complaints. On social media site Xiaohongshu, BYD owners have formed groups to discuss ways of demanding compensation, such as calling up sales representatives or contacting consumer rights agencies. The car owners joked that they had been “stabbed in the back” by the EV companies. Past price changes have even led to small-scale demonstrations, which are rare in China. In early 2023, Tesla buyers gathered at its stores to protest against sudden price cuts.

Ming Yang, a car owner in the eastern province of Anhui, told Rest of World she bought a BYD Seal sedan in late 2022 for 240,000 yuan ($33,337) to take advantage of government subsidies. To her surprise, BYD kept lowering its prices for the Seal model, while adding attractive new features over the next few months. By February, the sedan — now with leather seats and child safety locks — was priced at about 40,000 yuan ($5,556) less. The price cut also made the model much cheaper in the secondhand market. “Ordinary people like me worked hard for months to earn this money,” Yang wrote on her Xiaohongshu page. BYD did not respond to a request for comment from Rest of World.

To prop up the EV industry, the Chinese government has over the past decade offered generous subsidies, tax incentives, and favorable license-plate policies for buyers. With several lucrative private sectors under government crackdown, EV startups became a safe bet for internet giants, smartphone makers, and even property developers who launched their own car businesses. In 2019, the number of registered EV makers reached 486, and dropped to about 100 in 2023.

The price war has helped China’s overcrowded EV industry eliminate small players and consolidate resources, Zhang Xiang, a visiting professor in the engineering department of Huanghe Science and Technology University, told Rest of World. According to consulting firm AlixPartners, only 25 to 30 of more than 160 Chinese electric car brands are likely to remain financially viable by 2030.

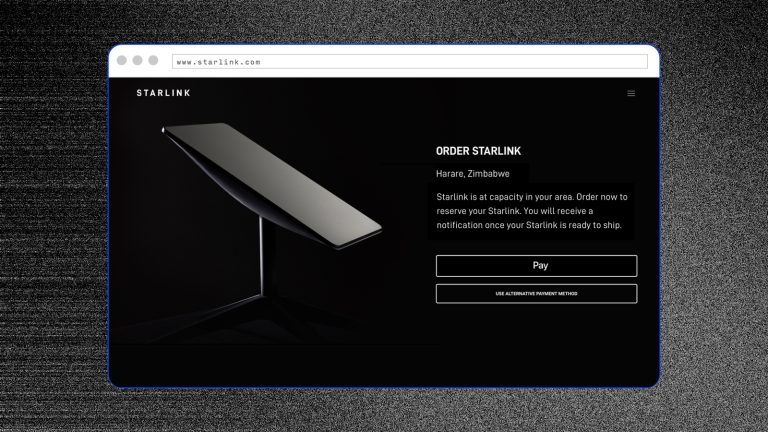

Compared to traditional gas-powered cars, EVs depend heavily on software to run their charging and driving systems as well as in-car entertainment and navigation. EV makers are able to keep fixing bugs and upgrading their services through over-the-air technology. When companies go bust, however, it’s often unclear who takes care of the software. The owners of WM Motor — which had sold nearly 100,000 vehicles but begun running out of funding since 2023 — have complained of system glitches, according to Chinese media reports. “All this is very new to the entire world,” Le said. “If a bug is serious enough and isn’t patched quickly, it could lead to more problems, even turning the car into a brick.”

HiPhi, a luxury brand that makes EVs equipped with refrigerators and champagne holders, is the latest company to run into trouble. Since launching its first model in 2020, HiPhi has failed to raise sales beyond a few thousand a year. In February, its parent company, Human Horizons, suspended operations. Founder Ding Lei told staff that he planned to spend the next three months exploring new investments and takeover options.

Meow Li, who bought a HiPhi Y for 369,000 yuan ($51,263) in 2023, told Rest of World she is now extra careful while driving — she’s worried she won’t be able to get the car fixed in case of an accident. Wang, a HiPhi X owner who only gave his family name for privacy reasons, said he would likely need to buy spare parts online for his 570,000-yuan ($97,174) car. HiPhi did not respond to a request for comment.

China’s car sales regulation requires suppliers to ensure parts will be available for at least 10 years if they stop producing a certain model, but enforcement has sometimes been difficult. “Buying from EV startups is like making a risky investment,” Sun Fangyuan, an auto industry adviser and influencer, told Rest of World. “If you bet on the bad ones, you will suffer from losses.” After witnessing the collapse of HiPhi and WM Motor, Sun said, consumers would more likely stick with the most established brands.

HiPhi has been so cash-strapped that employees seem to be peddling frozen food products on livestreams to earn extra cash. During a recent livestream on TikTok’s sister app, Douyin, HiPhi’s project director, Yang Yueqing, cooked a steak on an electric stove powered by a HiPhi Y SUV. Yang also showcased frozen shrimp cakes, taken out of HiPhi’s in-car refrigerator. “Shrimp is healthier than other meat,” he told the audience, while sitting in the car. All proceeds from the food sales will be used to support HiPhi’s after-sales services, Yang said.