ChatGPT impressed millions of internet users when it was first launched in December 2022. To Filipino Elmer Peramo, though, it felt familiar. After typing in some prompts and seeing the artificial intelligence chatbot’s responses, he noticed the technology was similar to a project he’d been working on with his team at the Advanced Science and Technology Institute, a government agency.

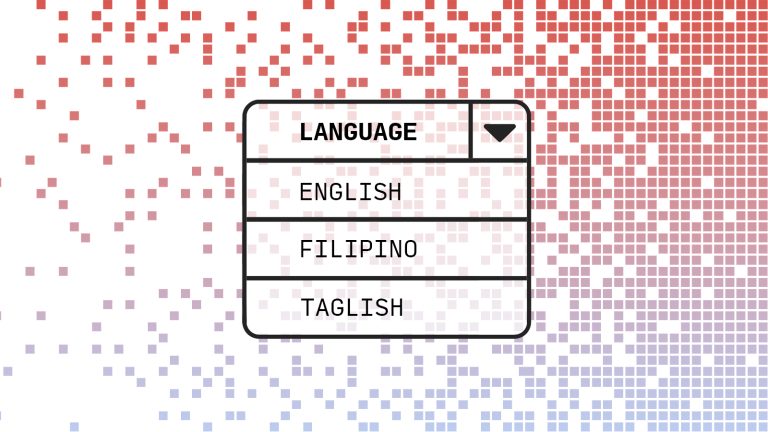

The project, iTanong, is like a local version of ChatGPT, Peramo told Rest of World. Through a web page, users can ask questions in English or Filipino, and receive AI-generated responses. It was conceived in 2017 — but at the time, Peramo and his 12-person team lacked the infrastructure and resources to build it. They plan to launch it next year.

Unlike search engines or chatbots, iTanong draws from both publicly available information and government databases holding private information. On top of doing everything a Google search or ChatGPT prompt can, Filipinos can use the program to apply to welfare programs, track benefit payments, or locate evacuation sites during a natural disaster, said Peramo.

“Through iTanong, we aim to level the playing field and democratize access to information,” he said.

Before being released to the public, iTanong will be deployed in government agencies, where it will serve as a replacement for the Citizen’s Charter, a document in the lobby of every government office in the Philippines that details the office’s policies. While the Citizen’s Charter is only updated once a year, iTanong can be updated as needed, Peramo said.

That would be handy for Bianca Aguilar, a product designer who’s looking for a new job. ITanong would be a “godsend” in helping with the laborious and often complicated pre-employment requirements like applying for a tax identification number, a health insurance ID, and police clearance, she told Rest of World.

“Navigating admin stuff like government services is still very confusing, so that’s one way I can see iTanong being helpful,” she said. It also helps that she can ask questions and receive information in Filipino, she added.

Only 55% of Filipinos say they can speak English fluently. ChatGPT is able to make grammatically correct sentences in the language, but its responses are not always conversational or natural enough for a Filipino speaker to understand easily.

“It still struggles with correct pronunciation and I’m not sure it works well with our language,” Aguilar said.

Popular large language models, such as OpenAI’s GPT, Google’s Gemini, and Meta’s Llama, are largely trained in English, excluding billions of people who speak languages that are not commonly found online.

“Minority languages and dialects, particularly those with smaller speaker populations, are often left out,” Nuurrianti Jalli, an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University’s media school, told Rest of World. “This exclusion stems from the lack of digital representation and resources dedicated to these languages.”

Filipino is considered a low-resource language in the world of natural language processing, meaning there is only a small amount of Filipino data available to train AI systems. To train iTanong, Peramo’s team draws from open-source data sets from the Common Crawl and Project Gutenberg. This material isn’t enough, though, so they are also manually training the model.

“We’ve resorted to using synthetically generated data, meaning we think of the common questions that the user would ask the system,” Peramo said.

“Through iTanong, we aim to level the playing field and democratize access to information.”

The Philippines ranks first globally in terms of AI interest, measured by monthly search volumes per 100,000 people. But implementation is uneven due to a glaring lack in infrastructure like data centers, high-speed internet connectivity, and cybersecurity measures. Only 22% of organizations in the country consider themselves fully prepared to use the emerging technology.

This is on top of the 20 million Filipinos who remain internet-poor: “Those in rural areas face barriers such as limited internet connectivity, lack of access to education, and even lower awareness of AI benefits,” Dominic Ligot, a data analyst and AI researcher, told Rest of World. “This will make it difficult for them to engage with AI technologies compared to urban centers like Metro Manila.”

Elsewhere in the region, AI is being more rapidly deployed. Singapore ranks third in the world — behind only the U.S. and China — in terms of AI investment, innovation, and implementation. Several firms in Indonesia are working on LLMs to preserve their local languages, while in Malaysia, the government is backing a new LLM in Bahasa Malaysia.

ITanong’s team is working alongside other research and development institutes within the Department of Science and Technology to advance the country’s AI implementation. For instance, Project Reiinn hopes to provide local internet connectivity and tablets to underresourced and underserved areas. Another project will deploy regional “virtual hubs,” or help centers for people with little AI knowledge.

ITanong is known primarily within academic and research circles. To achieve widespread adoption, collaboration between the government, industry, and educational institutions is needed, Ligot said.

“There must be a focus on enhancing digital literacy programs, improving internet access nationwide, and also ensuring ethical standards are upheld,” he said. Users also have a responsibility to “deepen their understanding and literacy of what AI is and what it can do for them.”

On iTanong, the plan is to add other local languages like Cebuano, Ilocano, and Hiligaynon by 2026, Peramo said. The platform will be available on mobile phones, and users will also be able record themselves asking questions rather than typing them out. But progress is slower than they hoped for, he said.

Government bureaucracy is an issue. Some local agencies don’t maintain databases, while others make use of unstructured formats. Funding is often delayed, Peramo said. “Sometimes, we present proposals during a certain time. By the time new funds roll in, the technology [we want to implement] is already passe,” he said.

With the iTanong project, the aim is to also build a culture of innovation in the Philippines, despite the challenges, Peramo said.

“Most of us are just working with what’s available to us,” he said. “But if we had a lot of researchers who are more forward-looking, and if we had policies on hand that favored progressive thinking, then I would say we would be further ahead than where we are right now.”