When Alois Kachere decided to order a Starlink kit after the company’s launch in Zimbabwe in September, he hoped to be the first person in his neighborhood to get the high-speed internet terminal.

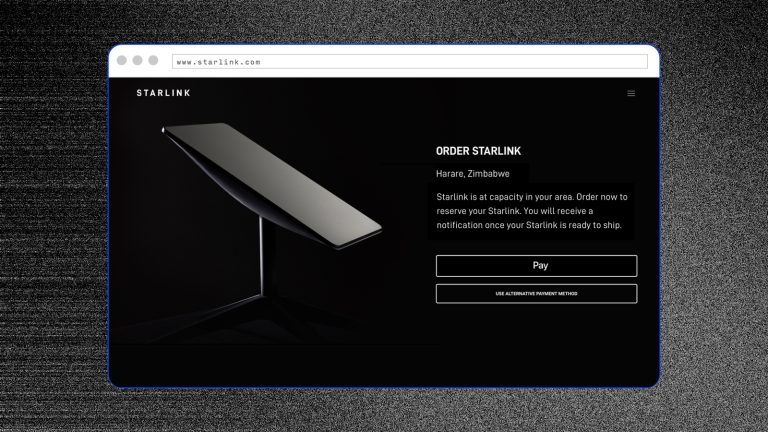

But others had beat him to it: “Starlink is at capacity in your area,” he read on the website. Starlink kits were sold out where Kachere lived in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital city. Overwhelmed by the demand, Starlink also sold out in other African countries, including major cities in Nigeria and some counties in Kenya.

“Even if it means I will wait until January, I don’t care.”

Kachere, a network engineer, doesn’t know how long he’ll have to wait to get his hands on a Starlink kit, but he’s resolved to do what it takes. He put down a deposit of $50 to claim a spot on Starlink’s waiting list. “Even if it means I will wait until January, I don’t care. As long as it’s not Econet, Telecel, and NetOne,” he told Rest of World.

Years of slow speeds, frequent outages, and exorbitant data costs are driving many Zimbabweans away from the country’s traditional internet service providers. Their dissatisfaction has prompted a rush for Starlink, and the service sold out within just four weeks of launch.

Starlink, a division of Elon Musk’s SpaceX, offers high-speed internet via low Earth orbit satellites, primarily targeting rural and remote areas where traditional internet infrastructure is lacking. By using satellites positioned close to Earth, Starlink delivers faster speeds and lower latency, making it ideal for underserved regions such as Africa and other developing countries.

Econet — the country’s largest mobile network operator, owned by billionaire Strive Masiyiwa — is “useless and yet very expensive,” according to Kachere. “They have taken us for a ride for a long time. Instead of lowering tariffs when we adopted U.S. dollars, they hiked fees,” he said, referring to 2009, when Zimbabwe adopted the U.S. dollar as its official currency and discontinued the hyperinflation-plagued Zimbabwean dollar.

Telecel, the smallest of the three mobile network operators operating in Zimbabwe, has for years experienced prolonged network outages that drive away customers.

Econet, Telecel, and NetOne did not respond to requests for comment.

Andrew Chitsa, a truck driver in Harare, also feels let down by the local internet service providers. He said that once Starlink is available, he will definitely order it.

“Data is very expensive in Zimbabwe when compared to other countries in the region,” Chitsa told Rest of World.

Before Starlink’s arrival, Zimbabweans endured exorbitant data costs, paying up to $20 for just 10GB of data per month. For the same fee, internet providers in neighboring South Africa provide unlimited data. Econet’s 30GB bundle costs $38, while NetOne charges $50 for 50GB.

In comparison, Starlink charges a one-time fee of $350 for the startup kit and an additional $50 per month for a standard package with unlimited data. Starlink Mini, a portable version of the standard kit, is just $30 per month for unlimited data.

“In the long run, it’s quite cheap for small businesses and residential customers that were subscribing to local network operators and ISPs,” Rashwhit Mukundu, Africa adviser at International Media Support, a press freedom organization, told Rest of World.

Starlink’s competitive rates have forced local providers to lower their prices. In June, Econet introduced high-speed broadband for $45 per month. Smaller ISPs like Powertel have also lowered their unlimited data prices to $30.

William Chui, a technician who assists locals with Starlink installations, told Rest of World he has installed about 300 kits across Harare’s affluent northern suburbs since the company’s launch. Demand continues to grow.

Chui said that wealthy Zimbabweans have been the earliest adopters. The high up-front cost of the Starlink kits makes them inaccessible to lower-income areas in Harare.

Jacob Mtisi, CEO of Hamsole, an information and communication technology company in Harare, predicted that local internet operators may retain urban customers due to their “robust infrastructure,” but that Starlink’s impact will be greater in rural and underserved regions.

Mtisi told Rest of World that local operators and ISPs need to adapt to the competitive landscape by improving their service quality, investing in infrastructure, and exploring partnerships with satellite providers. For example, Liquid Intelligent Technologies has already entered into a distribution partner agreement with Eutelsat Group, a satellite telecommunications operator, with the goal of offering low Earth orbit satellite services — the same technology that Starlink uses.

“The post-Starlink licensing period has been very good for business.”

In early November, Musk posted on X that Starlink’s management is “working to increase internet capacity in dense urban areas in Africa as fast as possible.”

On November 4, Harare and some surrounding areas were still “at capacity,” according to Starlink’s website. The business district in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second-largest city, had also hit its limit.

“Please note that there is still significant capacity outside of city centers,” Musk wrote on X.

Despite the bottlenecks, demand for Starlink in Zimbabwe remains high.

In a Facebook group devoted to Starlink, a user seeks a mini kit. Another looks for a roaming kit registered in Zimbabwe.

Black market dealers offer marked-up kits. In early November, the Zimbabwean police arrested five men for selling and distributing Starlink kits.

But technicians like Chui, who joined the bandwagon early by selling Starlink accessories like roof mounts and Ethernet adapters, have cashed in on the strong demand. Chui charges between $80 and $120 for his services.

“The post-Starlink licensing period has been very good for business,” he said.