Dog from Harappa, 2600–1900 B.C.E., terracotta, 1.9 x 5.3 x 3.3 cm (© Richard H. Meadow, Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan)

Vihara and stone bed (inset), Ajanta caves, 5th century, Aurangabad (photo: Arathi Menon, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Art is a wonderfully tangible pathway to past cultures. In the large collar of a tiny terracotta dog from Harappa, in present-day Pakistan, we learn about people and their dogs four thousand years ago. In beds made of stone inside rock-cut viharas (monastic houses) in the hillside of Ajanta, in India, we glimpse the lives of Buddhist monks in the first century B.C.E. And in pieces of furniture fashioned from ivory and bone found in Begram in Afghanistan, we get a taste of the luxury and artistic skill that people—much like you and I—cherished nearly two millennia ago.

A few considerations

South Asia (according to the modern designation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation), includes the following countries:

|

|

In this brief introduction to the art and cultures of South Asia from prehistory to c. 500 of the Common Era, we refer to these countries to aid in geographically orienting you to the material culture discussed. It is important to remember, however, that over the course of history, the sovereign nations of South Asia experienced both distinct and shared histories, and these often do not correspond to modern-day borders.

The artifacts, coins, and written records of empires and kingdoms that emerged and dissolved throughout history help us anchor the boundaries of people who shared a common lifestyle, language, and religion. In the study of prehistoric artifacts, other factors—such as shared technologies and ritual practices—help us recognize patterns of living that indicate geographically coherent cultures and societies.

Topography too (marked in yellow in the map above) influenced cultural and political histories. The Hindu Kush mountain range (in Afghanistan), the Himalayas (in Bhutan, Nepal, India, and Pakistan), the Thar desert (in northwestern India), the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, and the Lakshadweep Sea that surround the Indian peninsula, and the Palk Strait between India and the island nation of Sri Lanka, all played important roles in shaping the histories and the art histories of South Asia.

Prehistory

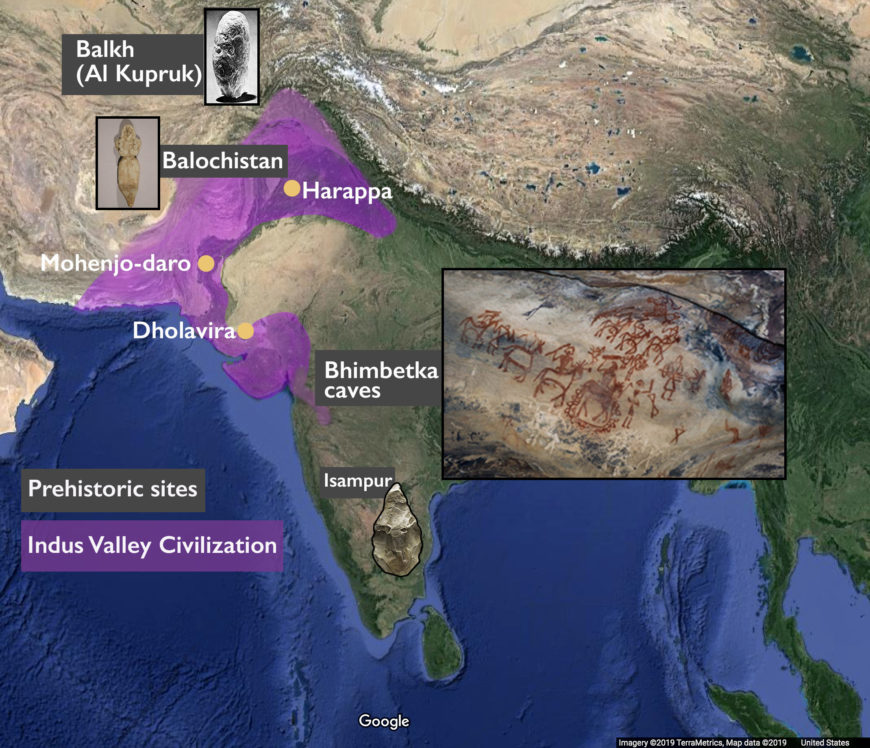

Archaeology can help us understand much about prehistoric civilizations. A stone tool, discovered in Isampur in India (see inset in the map below), for instance, confirms human settlement in the region as early as 1.1 million years ago.

Map 2: Prehistoric sites and the Indus Valley Civilization. Clockwise from left: Seated Mother Goddess, 3000–2500 B.C.E., Pakistan, Baluchistan (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); Sculpted face, c. 20,000 B.C.E., Aq Kupruk, Afghanistan (photo: CEMML, Colorado State University); Cave paintings, c. 9000 B.C.E., Bhimbetka, India (photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA-3.0); Handaxe, about 1.1 million years old, Isampur, India (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History).

Some of the earliest portrayals of ancient peoples in South Asia are found in the Bhimbetka caves, dated c. 9000 B.C.E., in central India. The paintings show figures dancing and humans hunting (see inset in the map above), as well as a person being hunted or attacked by an animal. Excavated tools, pottery, and figurines of animals and humans found in Balochistan, Pakistan, also tell us about the interests and activities of people from c. 7500–2500 B.C.E. In the inset in the map above is an artifact from Balochistan that is thought to represent a fertility or cult goddess. From a time more distant—c. 20,000 B.C.E.—is a limestone pebble with a face incised on it (inset in map above) from the archaeological site of Aq Kupruk II in the Balkh province of Afghanistan. The pebble poses interesting questions—who made it? And why?

The Indus Valley Civilization

Between 2600 and 1900 B.C.E., several settlements (see map 2 above) thrived around the river Indus which extends from the Tibetan plateau and flows into the Arabian Sea. These settlements—Indus cities have been excavated in Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan—are known collectively as the Indus Valley Civilization.

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro, with the Great Bath in the foreground and the granary mound in the background (photo: Saqib Qayyum, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Large sites such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in Pakistan have revealed highly efficient urban-planning, well-designed homes and neighborhoods laid out on a grid pattern, granaries, and public buildings all built with uniformly sized bricks. The Indus people were skilled in the management of natural resources; the site of Dholavira in Gujarat, India for instance, had a sophisticated system of water management. A complex writing system was also in use in this period, although sadly, the Indus script remains undeciphered.

Stamp seal and modern impression: unicorn and incense burner (?), c. 2600–1900 B.C.E., Indus (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Miniature terracotta figurines of a range of animals including the rhinoceros, birds, and dogs, and bullock drawn carts with drivers (see below) have been excavated from Indus sites. Whether they represent votive images or are simply children’s toys is as yet undecided. Board games, jewelry made of shells and beads, and stone and bronze figurines have also been discovered as have many steatite seals. These seals may have been used in trade and ritual and are distinguishable by their engravings of animals, humans, possibly divine beings, and, on occasion, unicorns!

Terracotta figures, c. 2500 B.C.E. Indus Valley Culture, Chanhu Daro, Pakistan (Brooklyn Museum)

The Vedic period

By c. 1300 B.C.E., speakers of Sanskrit (known as the Aryas) had settled in the northwest region of the Indian subcontinent. The Rigveda, the earliest of four Vedas (Sanskrit for “knowledge”)—a compendium of sacred scriptures on ritual, liturgy, and moral principles—is dated to this period. [1] The Vedas were a significant influence on the development of the Hindu religion. Like the material artifacts from the Indus Civilization above, the Vedas also carry glimpses of life in the Vedic period. We learn of the people who lived in the region prior to the arrival of the Aryas, as well as details on societal relationships, daily life, and the worship of gods and goddesses from Vedic hymns.

Scholars have been able to discern the eventual movement of people to the Gangetic plains of India (see map 5 below) from the three later Vedas—the Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. [2] Another important set of sacred texts, collectively known as the Upanishad, were composed sometime between the seventh and the fifth centuries B.C.E., and served as an elucidation of the Vedas. [3]

Buddhism

The Magadha region (roughly centered around Bihar and northeastern India, see map 5 below) would become a place of socio-religious debate and the birthplace of two major religions—Buddhism and Jainism—that were born in critical reaction to Vedic traditions. Some scholars have suggested that existing spiritual traditions in Magadha—the belief in rebirth and karma, for instance, was absorbed into Brahmanism (a precursor to Hinduism), Buddhism, and Jainism. [4]

Born Siddhartha Gautama in Lumbini, in present-day Nepal, the exact date of the Buddha’s birth is not known, but scholarly consensus dates his death around c. 400 B.C.E. [5] The Buddha’s teachings offered people a new path to salvation that was different from the ritual-based practices of the Vedic religion. You can read about Brahmanic Hinduism and Buddhism, including the life of the historic Buddha, jatakas, and the Buddha’s teachings here.

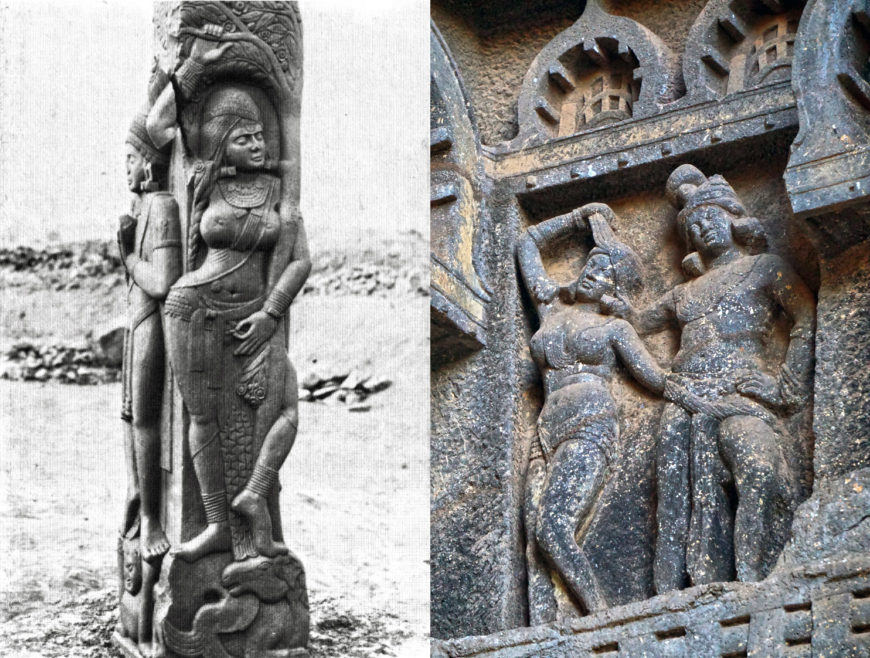

Buddhist monastic sites were adorned with narrative panels that celebrated the life of the Buddha—first in aniconic form and later in iconic form—as well as with a wealth of sculptural representations of men, women, animals, architecture, plants, and nature spirits, including yakshis (female goddesses), yakshas (male gods), and mithuna (couples) in a nod to pre-Buddhist traditions of reverence for fertility spirits.

Left: A yakshi and yaksha at Bharhut stupa, 1st century B.C.E., Madhya Pradesh (photo: public domain); Right: Mithuna, Karle Caves, Maharashtra, 2nd century (photo: Photo Dharma, CC BY-2.0).

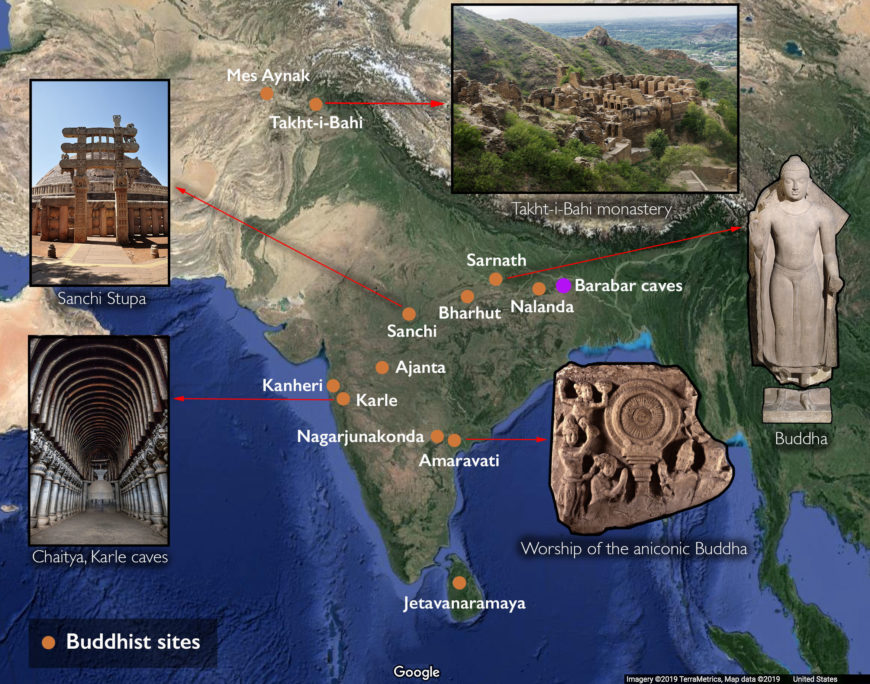

According to tradition, on his death, the Buddha’s cremated remains were distributed amongst nine clans. These relics came to be deposited in stupas (burial mounds) where they were then worshipped by the Buddha’s followers. By the early centuries of the Common Era, Buddhist sites were found throughout India, Afghanistan, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (see map 4).

Jainism

The founder of the Jain religion, Mahavira, is believed to be a contemporary of the Buddha. Like Buddhism, Jainism offered a path to salvation that was unencumbered by ritual. In Jain tradition, the twenty-four Jinas (Sanskrit for “victor”) who have overcome karma (the sum of a person’s actions) through a life of spirituality and goodness serve as role models for Jains and the path to salvation. Mahavira was the twenty-fourth and final Jina.

Left: Head of Jina, 2nd century, Kushan period, Mathura, red mottled sandstone, 8 1/2 x 7 3/16 inches (Cleveland Museum of Art); Right: Jain Svetambara Tirthankara in Meditation, 11th century, Solanki period, marble, 39 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Jinas are often shown in the meditative posture—either seated or standing—and emphasize austerity, immobility, and asceticism. Jain sacred imagery also involves images of nature deities as well as gods and goddesses such as Indra and Saraswati who are important deities in Hinduism. Images of the Jina may have the srivatsa (an ancient symbol) marked on their chest (see image on right, above), which distinguishes them from sometimes visually congruent images of the Buddha.

The Mauryas

In c. 326 B.C.E., Alexander of Macedonia invaded the Indian subcontinent. Alexander reached as far as the river Beas in present-day Punjab, India (see map 3) before he was forced to acquiesce the exhaustion of his army and their wish to return home. Alexander’s incursions had a lasting impact on South Asian history. One of his generals, Seleucus Nicator, would become the ruler of the Seleucid Empire which stretched from Anatolia to Afghanistan and Pakistan, including parts of the Indus Valley. Seleucus’s ambitions for more territory was curbed, however, by Chandragupta of the Maurya dynasty.

Pillar capital from Pataliputra, the capital of the Maurya dynasty in Bihar, c. 3rd century B.C.E., Patna Museum (photo: Nalanda001, CC BY-SA-4.0). Very little survives from the Mauryan period.

A treatise on war and diplomacy composed by the minister Kautilya in Chandragupta’s court offers a remarkable glimpse into the Mauryan kingdom and its policies. Along with rules for military regiments and economic strategy, this treatise, the Arthashastra, details policies on the exemption of taxes in times of disaster, guidelines for the use of state resources for the care of elephants and horses, and the protection of natural resources such as forests.

Much of Chandragupta’s life is misted by legend. What is certain is that he was a formidable ruler and warrior and that the Maurya kingdom under his rule was a prosperous one. Chandragupta’s son Bindusura maintained his father’s territorial gains, but his life too is poorly documented in contemporary accounts. According to tradition, Chandragupta converted to Jainism at the end of his life.

We have far more information about Chandragupta’s grandson, the emperor Ashoka. Ashoka too was a formidable ruler, but he vowed to rule, later in life, through non-violent means in adherence with the teachings of the Buddha. Ashoka helped spread Buddhism across the entire Indian subcontinent with the installation of pillars that proclaimed dhamma (Buddhist law). In addition to Buddhist philosophy, these edicts also detailed state provisions on social welfare for both people and animals.

Map 3: Distribution of Emperor Ashoka’s edicts, 3rd century B.C.E. Pillar inscription from Sarnath (public domain); Ashokan pillar at Vaishali, Bihar (photo: Bpilgrim, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Ashokan edicts have been found (see map 3) in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, and often in the language associated with the people who lived in those areas. Pillars were inscribed in Prakrit in the Kharoshthi and Brahmi scripts, Greek, and Aramaic, as well as in bilingual scripts. While we have not found Ashokan edicts in Sri Lanka, it is believed that Buddhism also spread to the island during Ashoka’s reign in the third century B.C.E. More edicts are likely to be discovered in the future; a team of archaeologists at UCLA is using geographic modeling to help accomplish just that.

Buddhist Monastic Sites

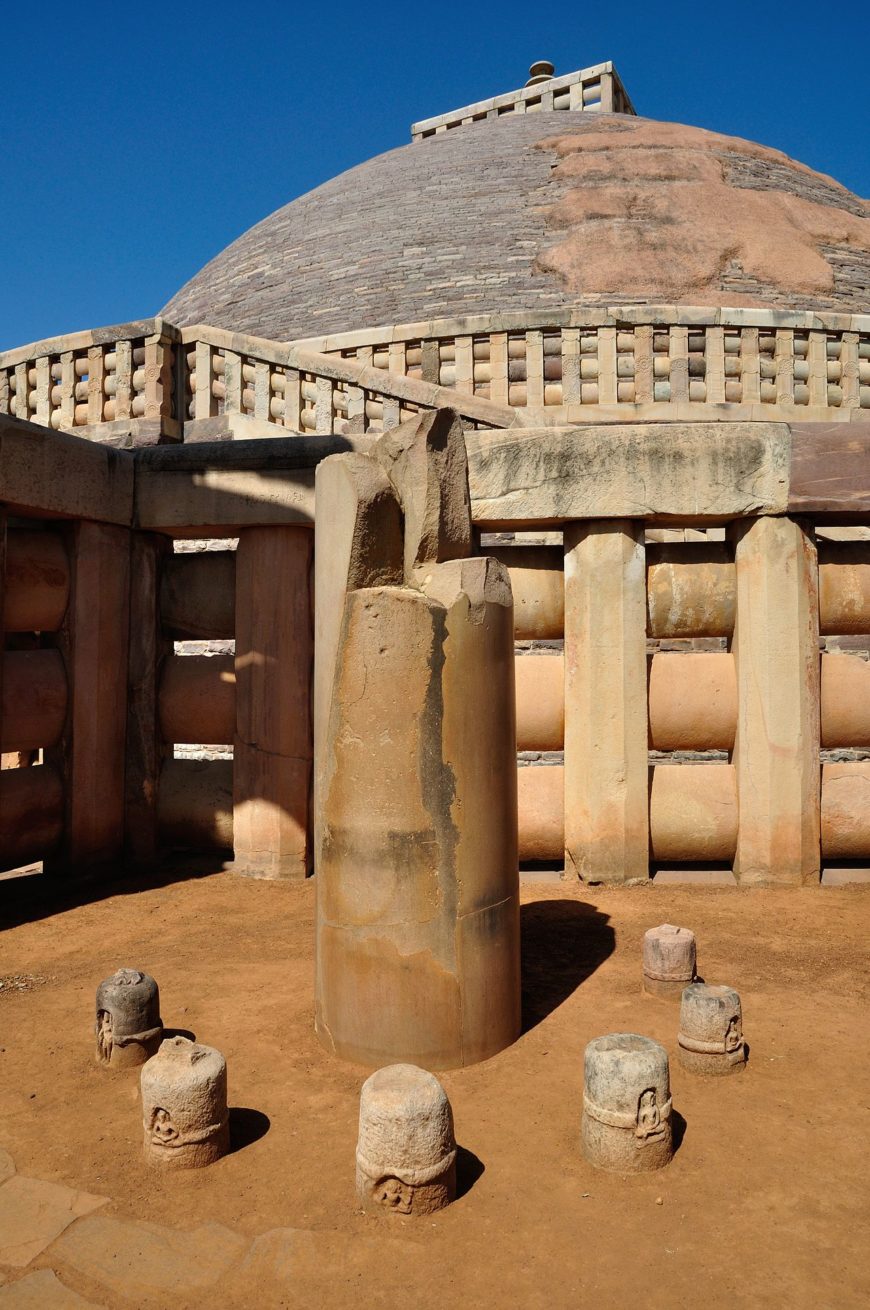

Ashokan pillar near Sanchi stupa, c. 3rd century B.C.E., Madhya Pradesh (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0)

A now broken Ashokan pillar at the great stupa at Sanchi, a Buddhist complex associated with the patronage of the emperor, was retained when the stupa was expanded to twice its size and faced with stone in the first century B.C.E. Stupas are quintessential monuments to the memory of the Buddha and are burial mounds for the relics of other important persons. Stupas were often built in the midst of large monastic settlements known as samgha(s).

As Buddhism spread, monastic complexes were established in sites in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nepal. The stupa of Jetavanaramaya is located in one of the oldest known samghas in Sri Lanka, and dates to the third century C.E. It is believed, however, that the oral Buddhist canon was written down during the reign of Sri Lankan king Vatthagamini (29–17 B.C.E.). [6] Other examples of well-known and early Buddhist sites include Amaravati, Bharhut, and Nagarjunakonda in India, Takht-i-bahi in Pakistan, and Mes Aynak in Afghanistan (see map 4).

Map 4: Select Buddhist rock-cut caves, stupas, and monasteries. Clockwise from left: Rock-cut chaitya, c. 120, Karle (photo: Kevin Standage, CC BY-SA-2.0); Sanchi stupa, c. 3rd century B.C.E., Madhya Pradesh (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0); Takht-i-Bahi Buddhist monastery, 2nd century (photo: Asif Nawaz, CC BY-SA-3.0); Buddha, 5th c, sandstone, Sarnath (The British Museum); Fragment of a dome slab showing the worship of the aniconic Buddha from Amaravati stupa, 2nd century, Andhra Pradesh (The British Museum).

Monastic sites often show multiple phases of construction spanning centuries, indicating the sustained patronage and popularity of Buddhism. Nagarjunakonda, in particular, also preserves a record of the expanding footprint of monastic complexes with its multiple stupas, prayer halls, temples, and housing accommodations.

Buddhist sites regularly received the patronage of both Buddhist and Hindu kings, as well as that of ordinary people, including Buddhist monks and nuns, merchants, and travelers. Sanchi is remarkable for the information it preserves on ordinary people. Inscribed on the great stupa are 631 donative inscriptions that tell us about the people—from merchants to monks to nuns—who contributed to the reconstruction and beautification of the stupa in the first century B.C.E. [7]

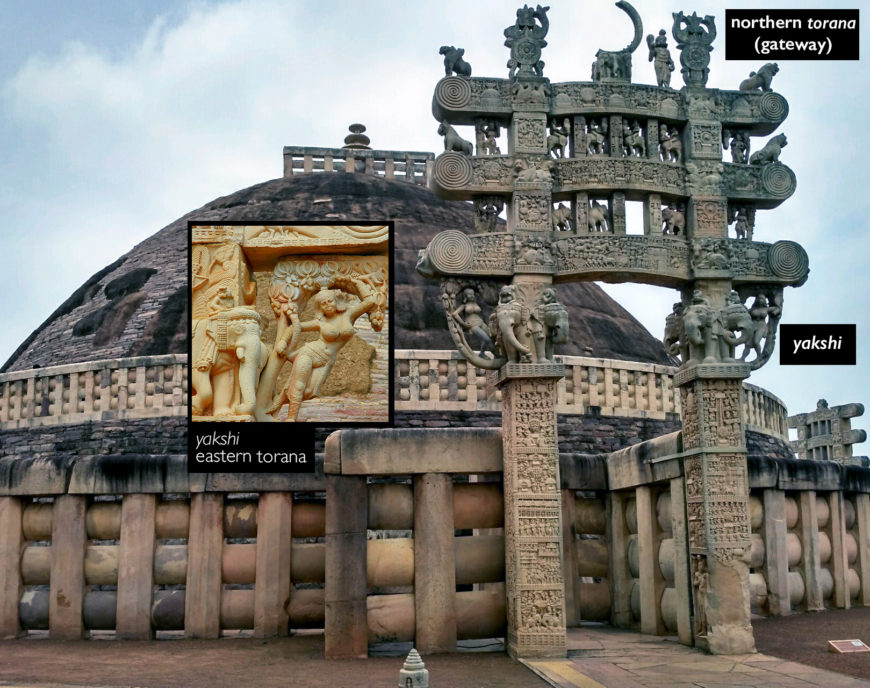

Great Stupa at Sanchi, 3rd century–1st century B.C.E., Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh (photo: AyushDwivedi1947, CC BY-SA 4.0; Tushar Pokle, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The stupa’s four extraordinary gateways (torana), once carried six images each of yakshis. These figures served as architectural brackets and as symbols of fertility—in obeisance to the auspicious quality associated with images of women on sacred structures. [8]

Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda, Sanchi, and countless other Buddhist monastic complexes were built at crossroads and close to trade-routes across the Indian subcontinent. This allowed monasteries to be of service to weary travelers and adhere to the Buddha’s instruction on the importance of sharing his teachings far and wide.

Buddhist samghas (monastic complexes) were also established in rock-cut caves. There are a large number of Buddhist rock-cut monastic caves in India—ranging from elaborately decorated to simply appointed. Caves hold a special significance in Buddhist tradition; according to Buddhist belief, when the Hindu god Indra went to visit the Buddha, he found him meditating in a cave.

Some of the most elaborate rock-cut caves are found at Ajanta and are dated to the fifth century of the Common Era, while a less embellished but no less stunning (rock-cutting is no easy task!) monastic complex can be found in the Barabar caves, dated to the third century B.C.E., in Bihar. The facade of the Lomas Rishi cave (image below) displays one of the earliest known representations of the “chaitya-arch”—an ornamented ogee shaped arch that replicated wooden construction in stone and became a commonly used feature in Buddhist rock-cut architecture in India. While the cave complex at Barabar belonged to an ascetic community known as the Ajivikas rather than the Buddhists, nearby inscriptions indicate that this community enjoyed the patronage of emperor Ashoka.

Entrance to the Lomas Rishi cave, Barabar, 3rd century B.C.E. (photo: Photo Dharma, CC BY-2.0)

On occasion, rock-cut caves and sculpture preserve glimpses of older architectural traditions. In the caves of Karle, Maharashtra, for instance, we find the original wooden beams from the first century B.C.E.; the use of wood (see inset in map 4, above) in the ceiling ribs was a purely decorative choice that imitated the style of wooden Buddhist chaityas (Buddhist chapels).

The adornment of rock-cut caves followed the same temporal progression of representing the Buddha—i.e., from aniconic (as emblems) to iconic (in human form). Whereas earlier Buddhist sites employed anionic symbols such as parasols, footprints, and even stupas to signify the presence of the Buddha, in time, representational imagery of the Buddha became the norm. The image below from Sanchi stupa shows an episode from the Buddha’s life known as the Great Departure. It represents the moment when the Buddha left his life in the palace for good.

The Great Departure, Sanchi stupa, eastern gateway, 1st century B.C.E. (photo: Anandajoti Bhikkhu, CC BY 2.0)

The parasols (shown in pink) indicate the Buddha’s movement from left to right. Once the Buddha disembarks at his destination and the horse returns to the palace, the Buddha’s absence on the horse is signaled by the absence of the parasol. The parasol remains with the Buddha who is now signified by a set of footprints. Also note how as the Buddha proceeded quietly into the night, the attendants helped carry the horse!

Rock-cut caves at Ajanta showing a solid stupa (left) and a stupa with the image of the Buddha (right), c. 2nd century B.C.E. to 5th century C.E., Aurangabad (photos: Arathi Menon, CC BY-SA-NC-4.0)

In general, in earlier rock-cut sites, we find stupas made of solid-rock serving as aniconic emblems of the Buddha and the focus of devotion. In later rock-cut chaityas, an image of the iconic Buddha was attached to the solid stupa (see image above), or the stupa was replaced altogether by the image of the Buddha. You can read about the complex ways in which the Buddha was portrayed in art here.

Despite the popularity of Buddhism in the centuries around the start of the Common Era, other religions continued to thrive. Two important Sanskrit Hindu epics—the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, for instance, are thought to have been composed in c. 300 B.C.E.–300 C.E. and 200 B.C.E.–200 C.E. respectively. [9]

The Kushans

Between the second century B.C.E. and the third century C.E., the Kushan empire became a dominant force in the northwestern part of the subcontinent. The Kushans were active in both sea and land trade and had capitals in Kapisa (near Kabul, Afghanistan), Peshawar, Pakistan and in Mathura, India. Kushan territory under the rule of the third emperor Kanishka (2nd century C.E.) also included, in addition to north India, what is today parts of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Two types of iconic Buddha images were produced during the Kushan period—the Gandharan and the Mathuran Buddhas—distinguishable by both style and medium. Just as Mathuran Buddhas followed the style of local sculptural traditions, in Gandhara, images of the Buddha followed a Greco-Roman aesthetic, thanks in part to the presence of plentiful Hellenistic imagery and Macedonian and Parthian influences in the region.

Left: Standing Buddha, c. 2nd–3rd century, Mathura style, Government Museum Mathura (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-3.0); Right: Buddha, possibly from Takht-i-bahi monastery, 3rd century, Gandhara style (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Coin of Kanishka, c. 130, ancient region of Gandhara, Pakistan (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Kushan emperor Kanishka is considered second only to Ashoka for his contribution to Buddhism. He is credited with the building of an enormous stupa (reportedly somewhere between 295 and 690 feet high) with multiple stories and thirteen copper umbrellas. Only the foundation of the building—itself 286 feet long—survives today in Shahji-ki-Dheri, outside Peshawar, Pakistan. [10] A gold coin has survived that was minted during Kanishka’s reign and likely shows that ruler.

Hundreds of ivory and bone furniture pieces, figurines, and a large number of practical and extravagant wares, produced in South Asia and as far away as China, Rome, and Roman-Egypt, dated to the Kushan period, have been discovered in Begram, Afghanistan. These objects tell us about the kinds of goods that travelled the Silk Road in the first and second centuries. By the second century, Buddhism had also travelled and spread farther east to Central Asia and China via these same routes. The earliest known translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese is dated to the second century C.E.

Ivory figurine, Begram, Afghanistan, 1st century (photo: JC Merriman, CC BY-2.0)

The golden age

By the early centuries of the first millennium, the Vedic religion had evolved into the Hindu religion. While a core tenet of Hinduism—the concept of the Brahman (omnipresent consciousness)—had already been formulated in the Upanishads, many of the gods and goddesses that we see in Hindu art are found in the Puranas (ancient stories) that were composed in this period.

Vishnu, 5th century, Gupta period, Mathura, red sandstone, 109 x 67 x 22 cm, National Museum, New Delhi (photo: Jen, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The rise of the Gupta dynasty (c. 320–647) marked an important time for art, architecture, and literature. It was also a period of strong global trade; scholars believe that the Gupta sculptural and temple-building style can be found in the early medieval remnants of Buddhist and Hindu art and architecture in Southeast Asia. A coin shows king Samudragupta, one of the Gupta dynasty’s most successful rulers and one who greatly expanded the dynasty’s power and territories. The inclusion of a goddess on the reverse side of the coin implies divine kingship in an effort to suggest that the king’s rule was mandated by the gods.

Coin showing the ruler Samudragupta (left) and a goddess (right), 330–376 C.E., gold (The British Museum)

Some of the most celebrated writers and composers of drama, poetry, and prose, lived in this period—Kālidāsa and Bānabhatta, among them. The number zero was invented as were Arabic numerals, which were referred to by Arabs as hindisat (“the Indian art”). This was also the era of great scientists; the astronomer Aryabhata in the sixth century calculated the solar year at 365.3586805 days and theorized that the earth rotated on its own axis. [11]

Standing Buddha, 5th century, Gupta period, Mathura, Mathura Museum (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY-2.0)

It was also during the Gupta period that a new type of Buddha image—the Gupta Buddha emerged. Buddha images in this period continued to be produced in Mathura, but also in Sarnath and in Nalanda (see map 4). Each area had access to quarries of a specific type of stone which have helped art historians determine where an image may have been produced.

Hindu art and architecture also flourished in the Gupta period. One of the most famous religious sites associated with the Guptas is the Udayagiri complex of rock-cut caves in Madhya Pradesh (see map 5). The Udayagiri Caves are made up of twenty caves, nineteen of which are dedicated to Hindu gods and date to the fourth and fifth centuries. There is also one Jain cave that is dated to the early fifth century.

Vishnu as the avatar Varaha rescuing Bhudevi, the goddess earth, Udayagiri cave no. 5, 5th century, Gupta period, Madhya Pradesh (photo: Asitjain, CC BY-SA-3.0)

Throughout the Gupta period, regional kingdoms led by independent rulers prospered. In most instances, there was also an easy relationship between the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain religions; as an example, the famous Buddhist rock-cut caves at Ajanta in Aurangabad enjoyed the patronage of the Hindu Vakataka dynasty.

In contemporaneous South India, the culturally cohesive region known as Tamilakam (see map 5) produced a valuable set of texts known as Sangam (old Tamil for “academy”) literature. These texts were composed in the old Tamil language and are rich in information on ancient South Indian kings, religious devotion, temple building, daily life, and even grammar.

Bhitargaon temple, 5th century, Gupta period, Uttar Pradesh (Ankitshilu, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Structural Hindu temples were also built in this period, although the choice of brick and other more perishable construction materials has meant that most have not survived. An exception is the brick temple at Bhitargaon in Uttar Pradesh (north India) which is dated to the mid-fifth century (see above). The style and the skill of the architects and builders of Bhitargaon, as well as of Deogarh—a sixth-century structural stone temple also in Uttar Pradesh—suggests that a highly developed tradition of temple building was present by this point in time.

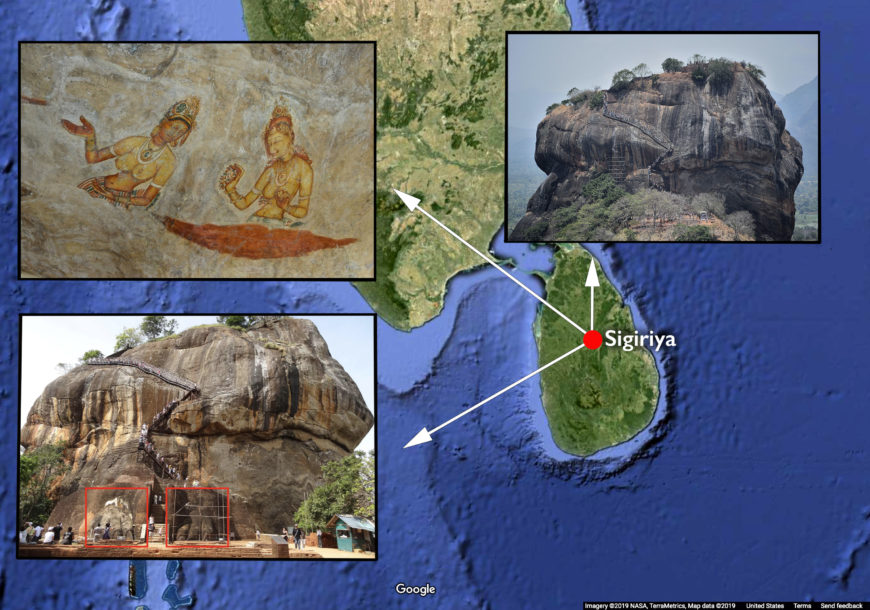

In fifth century Sri Lanka, a ruler named Kassapa built an extraordinary palace fortress atop a hill in his new capital. The site gets its name—Sigiriya—after “lion rock,” thanks to its enormous gateway in the form of a lion, of which only giant paws built from brick survive (see inset in map 6). Kassapa’s palace once included gardens and lakes and dozens, perhaps hundreds of mural figures of women that have been interpreted by scholars as either apsaras (heavenly beings) or ladies-in-waiting. Roughly 22 figures remain today.

Map 6: Sigiriya, Sri Lanka, 5th century C.E.; clockwise from left: Lion gateway (Cherubino, CC BY-SA 3.0), mural painting of female figures (Brian Ralphs, CC BY-2.0), and view of the Sigiriya fortress (Teseum, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Also at Sigiriya is a gallery known as the mirror wall (once a wall with polished plaster) as well as 685 instances of graffiti dating between the eighth and the tenth centuries. [12] Aside from its association with its patron king, Sigiriya is an important site in the history of Buddhism and is mentioned in the Sri Lankan Buddhist chronicle the Culavamsa.

Trade and exchange

Ivory statuette found in Pompeii, c. 1st century C.E. (Museo Archeologico Napoli)

Before we move on to the next section of this three-part introduction to South Asia, a word is necessary on the region’s long history of contact and exchange with other parts of the world. The Gupta period enjoyed trade with Southeast Asia and even older networks of trade existed along the Silk Road and in the Indian Ocean. Scholars have also suggested that trade brought beads and precious stones from the Indus Valley to Mesopotamia as early as the third millennium B.C.E.

In the first century of the Common Era, a Greek sailor wrote the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea—a text that provides remarkable details on thriving trade by sea and by land in the Indian Ocean. We learn of routes, the best times to travel, the monsoon winds and their impact on sea travel, the commodities that were traded, the money exchanged, and more.

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder similarly records valuable information in his Historia Naturalis from the year 77 C.E. He reported, for instance, on which pirate-filled ports to avoid in western India and wrote somewhat sardonically of his disdain for his fellow Romans’ obsession with pepper and luxury goods.

Buddhist sites also acknowledge the cosmopolitan milieu of ancient South Asia. At a rock-cut cave in Karle (see map 4), inscriptions dating to the early second century C.E. record gifts of stone pillars by yavanas (foreigners). Roman coins from the first and second centuries have also been found in Nagarjunakonda, as well as near the ancient port town of Muziris in Kerala. In addition, Roman amphorae have been found in the archaeological site of Arikamedu in Tamil Nadu (see map 5).

As Pliny tells us, much also travelled abroad. The most famous of all objects to travel to Rome was an ivory figurine of a woman. A little under ten inches tall, this astonishing figurine with hair and jewelry much like that of the women carved on the toranas at Sanchi somehow survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 C.E. and was discovered in the ashes of Pompeii.