The European baroque is reinterpreted with Andean building technology in this mission church on the old Inka road.

The Church of San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, 1570–1606, stone, adobe, kur-kur, Andahuaylillas (Peru). Speakers: Norma Barbacci, World Monuments Fund, and Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] We’re in the Offices of the World Monuments Fund in New York City, in the Empire State building. We’re talking about a really important project that WMF oversaw in Peru that has to do with these extraordinary early Baroque churches.

[0:20] The geography of Peru is incredibly varied. There are stark deserts and jungles, but it also incorporates one of the highest mountain ranges on Earth, the Andes.

Norma Barbacci: [0:31] We’re going to be talking about the Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas, located in the Andes.

Dr. Zucker: [0:37] Before the Spanish arrived, this area had been controlled by the Inca Empire. This was an extremely sophisticated empire that had conquered a series of empires even before it.

[0:47] Primarily what the Spanish were interested in was increasing their wealth through the labor that could be gotten from the Indigenous populations, but also from raw materials that could be brought back to Spain, especially and most famously, gold.

[0:59] The Spanish would claim an enormous amount of land that stretches from what is now northern California all the way to the southern tip of South America.

Norma: [1:07] When the Spanish came, most of this region, especially in South America, was connected by a network of roads known as the Inca Road or the Qhapaq Ñan. These churches were built, stretching all the way from Cuzco to the jungle of Peru. They were known as missionary churches, designed to convert.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] There was a religious aspect to conversion, but there was also a political aspect, which is [that] you could, in that way, control the population.

Norma: [1:38] The Jesuits, in this particular case, were considered as the more educated of the religious orders.

Dr. Zucker: [1:43] It’s important also to think about the Jesuits as soldiers of the pope that were to go out into the world to combat heresy and to convert as many souls around the world as possible. When you go into the church of the Jesuits in Rome, you see very explicit references to going to the four great continents to bring those souls to the church.

Norma: [2:04] One of the most important products of this whole Counter-Reformation movement was the Baroque, but when it came to America, it became infused with some original techniques and aesthetic preferences. What we call the Andean Baroque became a new, independent style.

[2:16] As you can see, the facade has got Renaissance elements, but then once you go through the portal, it’s an explosion of Baroque.

Dr. Zucker: [2:28] When we look closely at the facade, we see this brilliantly-colored entrance, with a porch above that would have been used to preach from. Even from the outside, we can see this wonderfully complex mix of cultures that is informing the architecture.

[2:38] You had mentioned the classical. You can see that especially in the pediment. You can see that in the triumphal arch of the entranceway and, of course, the classicizing pilasters. All of this is coming from the Greco-Roman tradition.

Norma: [2:54] Then right above, you see an element that is what we would consider mudéjar architecture from Spain.

Dr. Zucker: [3:00] What we’re talking about is the architectural style that was developed by the Muslims when they occupied Spain. What happens is that the Spanish Christians will reconquer the Spanish peninsula. This is a visual vocabulary that refers to conquest, the conquest and the triumphalism of Christianity. Let’s go inside.

Norma: [3:20] Now, you see the stark contrast between the more classical facade into this explosion of Baroque, where every square inch of wall is covered with some kind of decoration.

Dr. Zucker: [3:25] It must have been so impressive when this was first painted. The ceiling is a kaleidoscope. We see this emphasis on pattern that really does remind me of the Islamic traditions. We see that especially in the very fine coffering.

Norma: [3:40] The local techniques of construction were used. For example, instead of wood, the artesonado ceiling was built of this technique called “kur-kur.” Kur-kur consists of a combination of cane and mud that was then shaped to look like wood and then painted over with decorative motifs.

Dr. Zucker: [4:03] This wonderful example of this local building technology, which actually goes back in Andean history for thousands of years, being incorporated into this modern Christian environment and made to look like the ceilings that we would expect to see in Europe.

[4:16] It’s important to remember that the artisans responsible for the building itself would have been local Indigenous peoples. The entire space feels so sculptural and so colorful.

Norma: [4:27] That’s probably the reason why this church has been known in Peru as the Sistine Chapel of the Americas.

Dr. Zucker: [4:28] There’s so much that we could look at. The altar is magnificent. But let’s look at one particular painting of the Last Judgment, because that subject became quite common at this moment in colonial South America, in colonial Peru.

[4:41] We’re looking at a mural — fresco — that is known as “secco fresco.” That is, it’s painting that’s been done directly on a dry wall.

Norma: [4:48] The purpose of all these paintings was propaganda. The people that lived here, they didn’t know how to read. This is how the indoctrination happened, through visual means. This painting by Luis de Riaño, done in the early 17th century, depicts how people that were good would go to heaven.

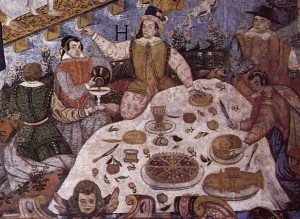

Dr. Zucker: [5:06] We have this fabulous feast laid out before us, but the soul that is especially good has ignored that bounty. It is willing to do the hard work of salvation. He walks along a path that is hard, that people fall off of, but his eyes are fixed on those that inhabit heaven. We see a representation of this city of the Heavenly Jerusalem just beyond.

Norma: [5:28] And then we could see the mural on the opposite side, then.

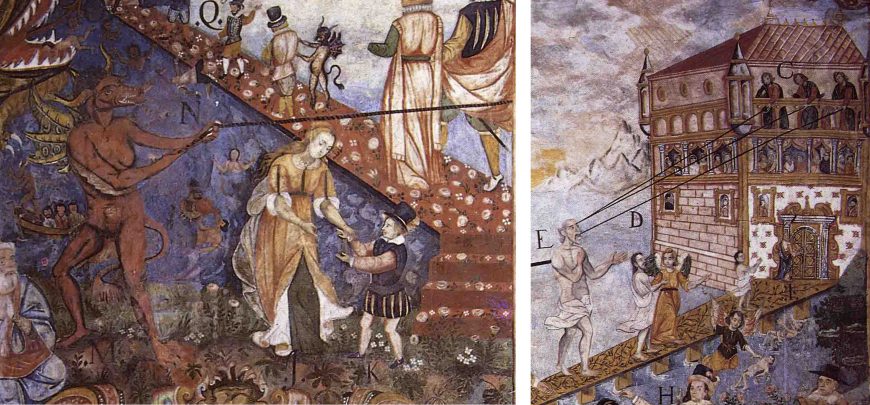

Dr. Zucker: [5:31] So here we have a pathway that looks easier, it’s strewn with flowers, but of course, it leads to doom, it leads to hell. We see the mouth of hell, we see the devil, who seems to be pulling at people even on the other side.

[5:44] What’s interesting is that this is a variant on a traditional Last Judgment scene, but there you generally see souls that are being awoken from the dead who have already made their choices, but here it’s much more immediate. It’s as if the Indigenous peoples who are being brought into this church are being faced with this immediate choice, “What path are you going to take?”

[6:10] This was especially important for the Jesuits, who were doing their best to stamp out what they saw as the idols of the Indigenous peoples.

[6:15] Even as these paintings were being made, there would still have been plenty of references not only to the religion of the Incas, but the religion of the cultures that had come before the Incas.

[6:24] In fact, the foundation is built of stone, including stone that’s been repurposed from older Inca structures, but above that, we actually have what is primarily an adobe building — mud mixed with some straw to help bind it.

Norma: [6:39] In the last four or five years, World Monuments Fund has been carrying a conservation campaign in the Church of Andahuaylillas. They started with the conservation of the artesonado ceiling, but then we realized that was not enough. We had to address the structure of the whole church and then we started thinking that if we protect the church, we have to also secure the whole town.

Dr. Zucker: [7:02] We generally think of the work of art in isolation, but your project exposes the way in which a painting is part of a building, and a building is part of a community.

Norma: [7:15] That’s why part of our conservation and restoration work included a training program for 15 young people, who were given the tools that they needed to actually become stewards of their own cultural heritage and their own patrimony.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] This is especially critical because development is forcing change on these communities.

Norma: [7:30] Even though Andahuaylillas is a relatively well-preserved town, you see these new constructions that they are built [with] concrete block and blue glass, and bathroom tile on the facade, and those are not part of the tradition and the aesthetic integrity of the town, but they’re also very bad environmentally.

[7:49] Adobe is a thermal material, it actually collects heat during the day and so the interiors are cool, and at night they release heat.

Dr. Zucker: [7:57] And if the local community is really a part of the conversation about maintaining its heritage, really thoughtful and considered decisions can be made about development going forward.

Norma: [8:06] So having a community that is on your side in terms of preservation is much better than just setting up laws and regulations. We’re not proposing to freeze this town. Obviously this town is going to develop and grow, but without losing the important aspects of what is part of their cultural heritage.

[music]

San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru, 16th century (photo: Bex Walton, CC BY 2.0)

The Sistine Chapel of the Americas

The Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas located outside of Cuzco contains an expressive decorative program that has earned it the title of the “Sistine Chapel of the Americas.” Filled with canvas paintings, statues, and an extensive mural program, the level of artistry and extravagance afforded to this church certainly rivals its counterparts in Renaissance Italy.

Nave looking toward the mural depicting The Paths to Heaven and Hell, San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru (photo: courtesy World Monuments Fund)

One of the church’s most well-known images is the mural painted on the interior entrance wall depicting an allegory of good and bad faith.

Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, c. 1626, San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru (photo: courtesy World Monuments Fund)

The subject matter

Painted by the criollo artist Luis de Riaño and Indigenous assistants, The Paths to Heaven and Hell transmits an important message to parishioners as they exit the church of the moral decisions they will confront on their spiritual journey. The two paths refer directly to a biblical passage which states,

Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it / But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.Matthew 7:13–14

Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell. RIght: detail of the Devil holding a rope, and an allegorical female figure guiding a young man; right: the soul on the righteous path to the heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

A nude figure wearing nothing but a white sheet around his waist walks cautiously down the narrow and thorny path to the Heavenly Jerusalem, with three lines emanating from his head that lead to a representation of the Holy Trinity as three identical male figures. A thick rope also connects his back to the composition on the left of the doorway, where the Devil attempts to pull him over to the left side.

Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the feast, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the Hell mouth, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

At the foreground of the scene is a banquet attended by four individuals feasting on wine, fish, bread, pie, and fruits. A mouth of Hell rears its head to the left of the path to Hell, its mouth agape with a naked sinner falling into his maw.

At the forefront of the scene is an allegorical female figure guiding a young man standing directly below the rope held by the devil. The path culminates at a castle engulfed in flames guarded by deer poised on the roof with bows and arrows.

The paths to Heaven and Hell were familiar tropes in medieval Christianity, with frequent representations in paintings, manuscript illuminations, and stage sets. Despite its decline in popularity in Europe by the Renaissance, this type of allegorical imagery carried great import in the colonial Andes.

The didactic iconography, painstakingly labeled with relevant biblical passages, was ideal for preaching Catholic doctrine to Andean parishioners. In fact, it is highly likely that Juan Pérez Bocanegra, the parish priest who commissioned the murals and accompanying decorative program, would have conducted his sermons using the murals as a focal point.

A New Jerusalem in the Andes

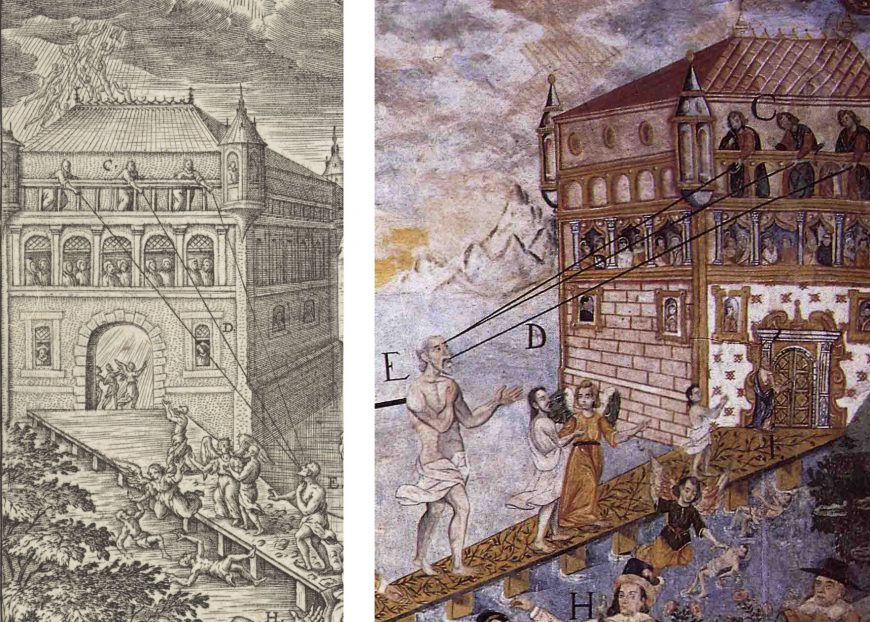

The mural is based on a print by Hieronymus Wierix entitled The Narrow and Wide Path, which Riaño copies relatively faithfully. One significant modification, however, can be found in the depiction of the path to Heaven. In the mural version, Riaño has added an additional figure at the doorway to the Heavenly Jerusalem holding a key. This individual likely represents Saint Peter the Apostle, the patron saint of Andahuaylillas. As the universal head of the church, Saint Peter held the keys to the kingdom of Heaven. Parishioners were thus given the implicit message that the church of their very community constituted a New Jerusalem on Andean soil. Indeed, the act of entering and exiting the church left congregations with a palpable reminder of the spiritual pilgrimage necessary for attaining salvation—and one that could be understood within the immediate parameters of their existence rather than as a place only to be visualized and imagined.

Left: Hieronymus Wierix, The Narrow and Wide Path, detail of the Heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1600; right: Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the Heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

The path to Hell also contains an intriguing detail that is only visible upon close inspection of the mural. Three barely visible figures are seated in a devil-driven canoe beneath the mouth of Hell. The central figure wears an Inka-style tunic with a checkerboard pattern around the collar. Such regalia would have been worn by curacas, or local Indigenous leaders. Another nearby Indigenous figure ingests liquid from an Inka-style aryballos vessel called an urpu, probably filled with chicha. The figures differ dramatically from the rest of the mural in both content and style. They are painted using rougher strokes, indicating the hand of an assistant to Riaño. Moreover, the cultural specificity of the figures, linking them directly to the Inka past through objects and regalia, suggest that the assistant was of Indigenous background.

Luis de Riaño and Indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of Indigenous figures behind the Devil, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

Despite the obvious visual conflation of Andean ritual practices in association with the Christian concept of Hell, these figures were granted visibility in a religious arena that sought to eradicate Andean ancestral cultures. The Paths to Heaven and Hell infuses Christian iconography with local referents to facilitate a more personalized and culturally meaningful point of access for the seventeenth-century parishioners of Andahuaylillas.