The Lindisfarne Gospels, left: Saint Matthew, portrait page (25v); right: Saint Matthew, cross-carpet page (26v), c. 700 (Northumbria), 340 x 250 mm (British Library, Cotton MS Nero D IV)

The dark ages?

So much of what the average person knows, or thinks they know, about the Middle Ages comes from film and tv. When I polled a group of well-educated friends on Facebook, they told me that the word “medieval” called to mind Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Blackadder, The Sword in the Stone, lusty wenches, feasting, courtly love, the plague, jousting and chain mail.

Perhaps someone who had seen (or better yet read) The Name of the Rose or Pillars of the Earth would add cathedrals, manuscripts, monasteries, feudalism, monks and friars.

Petrarch, an Italian poet and scholar of the fourteenth century, famously referred to the period of time between the fall of the Roman Empire (c. 476) and his own day (c. 1330s) as the Dark Ages. Petrarch believed that the Dark Ages was a period of intellectual darkness due to the loss of the classical learning, which he saw as light. Later historians picked up on this idea and ultimately the term Dark Ages was transformed into Middle Ages. Broadly speaking, the Middle Ages is the period of time in Europe between the end of antiquity in the fifth century and the Renaissance, or rebirth of classical learning, in the fifteenth century and sixteenth centuries.

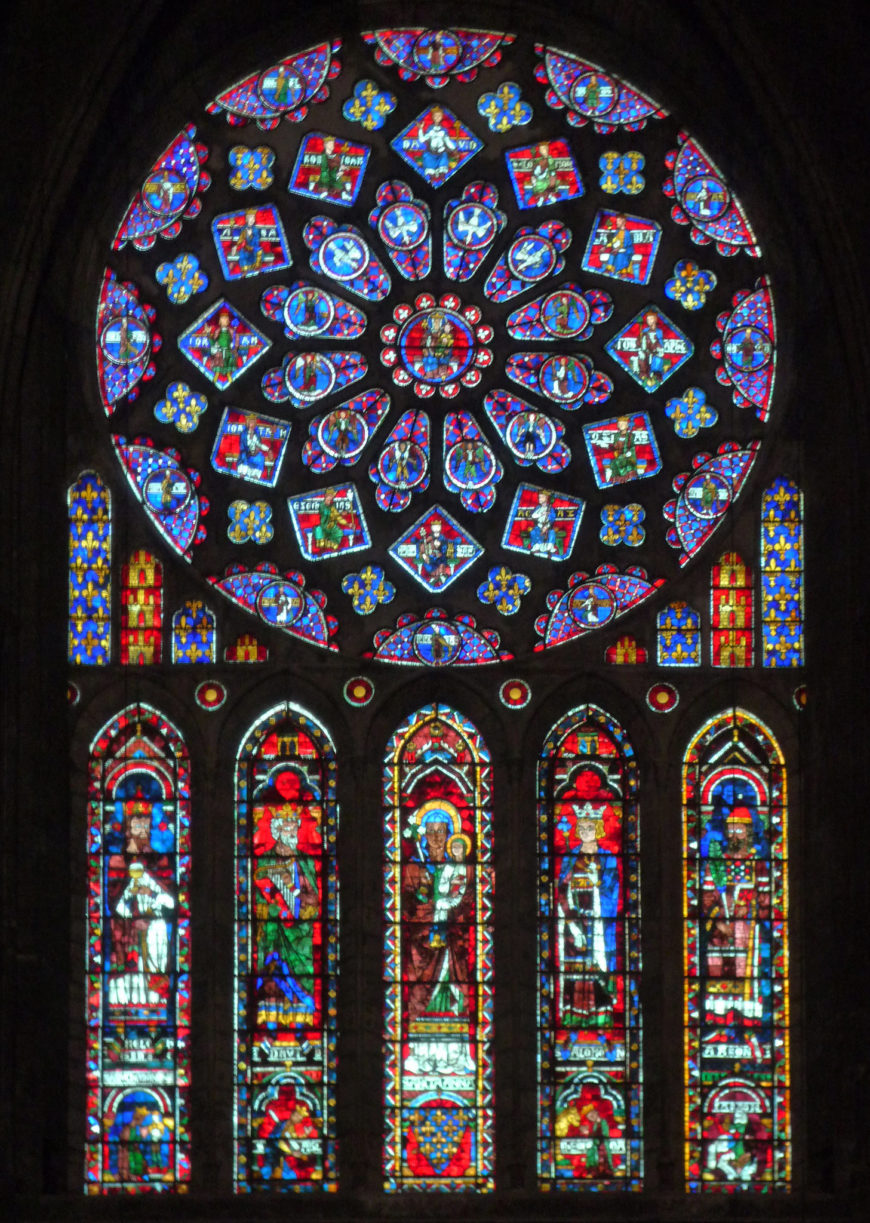

North Transept Rose Window, c. 1235, Chartres Cathedral, France (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Not so dark after all

Characterizing the Middle Ages as a period of darkness falling between two greater, more intellectually significant periods in history is misleading. The Middle Ages was not a time of ignorance and backwardness, but rather a period during which Christianity flourished in Europe. Christianity, and specifically Catholicism in the Latin West, brought with it new views of life and the world that rejected the traditions and learning of the ancient world.

During this time, the Roman Empire slowly fragmented into many smaller political entities. The geographical boundaries for European countries today were established during the Middle Ages. This was a period that heralded the formation and rise of universities, the establishment of the rule of law, numerous periods of ecclesiastical reform and the birth of the tourism industry. Many works of medieval literature, such as the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy, and The Song of Roland, are widely read and studied today.

The visual arts prospered during Middles Ages, which created its own aesthetic values. The wealthiest and most influential members of society commissioned cathedrals, churches, sculpture, painting, textiles, manuscripts, jewelry and ritual items from artists. Many of these commissions were religious in nature but medieval artists also produced secular art. Few names of artists survive and fewer documents record their business dealings, but they left behind an impressive legacy of art and culture.

Byzantium

When I polled the same group of friends about the word “Byzantine,” many struggled to come up with answers. Among the better ones were the song “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” sung by They Might Be Giants, crusades, things that are too complex (like the tax code or medical billing), Hagia Sophia, the poet Yeats, mosaics, monks, and icons. Unlike Western Europe in the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire is not romanticized in television and film.

In the medieval West, the Roman Empire fragmented, but in the Byzantine East, it remained a strong, centrally-focused political entity. Byzantine emperors ruled from Constantinople, which they thought of as the New Rome. Constantinople housed Hagia Sophia, one of the world’s largest churches, and was a major center of artistic production.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532–37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Byzantine Empire experienced two periods of Iconoclasm (720s–787 and 815–843), when images and image-making were problematic. Iconoclasm left a visible legacy on Byzantine art because it created limits on what artists could represent and how those subjects could be represented. Byzantine Art is broken into three periods. Early Byzantine or Early Christian art begins with the earliest extant Christian works of art c. 250 and ends with the end of Iconoclasm in 843. Middle Byzantine art picks up at the end of Iconoclasm and extends to the sack of Constantinople by Latin Crusaders in 1204. Late Byzantine art was made between the sack of Constantinople and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

In the European West, Medieval art is often broken into smaller periods. These date ranges vary by location.

| Early Medieval Art | c. 500–800 |

| Carolingian Art | c. 780–900 |

| Ottonian Art | c. 900–1000 |

| Romanesque Art | c. 1000–1200 |

| Gothic Art | c. 1200–1400 |