Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

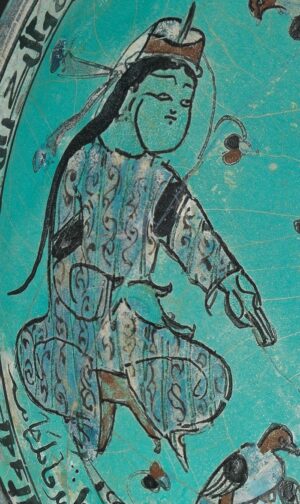

Figure reciting poetry (detail), Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the center of this 12th-century ceramic bowl we see two beautifully dressed figures sitting on a throne or takht. They are surrounded by four additional figures, one on either side, and two behind the throne. They tilt their heads, appearing to listen intently to the man sitting opposite them, who gestures forward as if in mid-speech. This figure is reciting poetry. They appear in a peaceful outdoor setting, where we see fish swimming in a pond and birds gathering at their feet and flying overhead.

Figures on the takht, Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

We are looking at a depiction of a majlis, a gathering of members of the royal court and intellectuals for the public recitation of poetry. The artist paid attention to small details to give life to the motif. The figure seated on the throne closest to us is distinguished from the rest by a distinctive headdress, perhaps a crown. He raises his hand as if responding to the skillful recitation performed by the figure opposite. The courtier to the left of the takht appears to rest his body on the throne, rapt by the poetic performance.

Poetry is central to this bowl—Persian and Arabic poems encircle the vessel on both its exterior and interior. Interestingly, at least one of the poems adorning its surface was composed by Abu Zayd who also made and decorated this bowl. Abu Zayd is regarded today as perhaps the most famous potter of medieval Iran. Signed and dated to 1186 C.E., this bowl is Abu Zayd’s earliest known work, and already represents his accomplishments in his craft.

Examples of minaʾi and lusterware, 12th–13th century. From left: Minaʾi bowl with enthroned ruler, 13th century, Kashan, Iran (Victoria & Albert Museum); Abu Zayd, Star tile with prince on horseback, 1211 C.E., fritware with luster decoration, 27.5 x 26.5 x 1.5 cm, Kashan, Iran (Museum of Fine Arts Boston); Abu Zayd, lusterware plate with mystical allegory of the quest for the Divine, 1210 C.E., stonepaste painted overglaze with luster, 35.2 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (National Museum of Asian Art); jar with hunters, 12th–13th century, stonepaste with minaʾi decoration, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

New ceramic technologies and experimenting with glazes: minaʾi and luster

Abu Zayd’s bowl is made with a new ceramic technology called stonepaste. The development of stonepaste in the tenth and early eleventh centuries shaped ceramic production across Egypt and Central Asia. Although it was neither expensive nor luxurious, the advantage of stonepaste was that it could be fashioned into thin walled ceramics, which evoked the highly valued porcelain vessels imported from China. This new medium triggered experimentation with inventive shapes, including functional vessels, tiles, and figural sculpture, as well as new decorative approaches. [1]

Abu Zayd’s stonepaste bowl has a turquoise underglaze and polychrome decoration in the minaʾi technique—one of the most up to date ceramic techniques of his time. Vessels produced with mina’i painting involved applying decoration—in this case color, and occasionally gilding—to an already finished (fired and glazed) product. Minaʾi wares were produced over a white or turquoise glazed base and fully decorated with detailed figural paintings of courtly life, including musicians, dancers, and hunting, as well as narrative scenes and astrological motifs. Minaʾi ware were widely sought after and eventually produced on an industrial scale for a range of patrons, from individuals purchasing in the open market to commissions produced for elite members of the ruler’s court. However, the production of mina’i ware was short lived, lasting only through the early thirteenth century, when they were eclipsed by lusterware, another popular ceramic form. Lusterware became one of the most prized ceramic types associated with the luxury arts, and were widely produced and traded across the Islamic world and later across western Europe. Abu Zayd contributed to the refinement of both of these techniques, producing some of the most complex examples of these glazes.

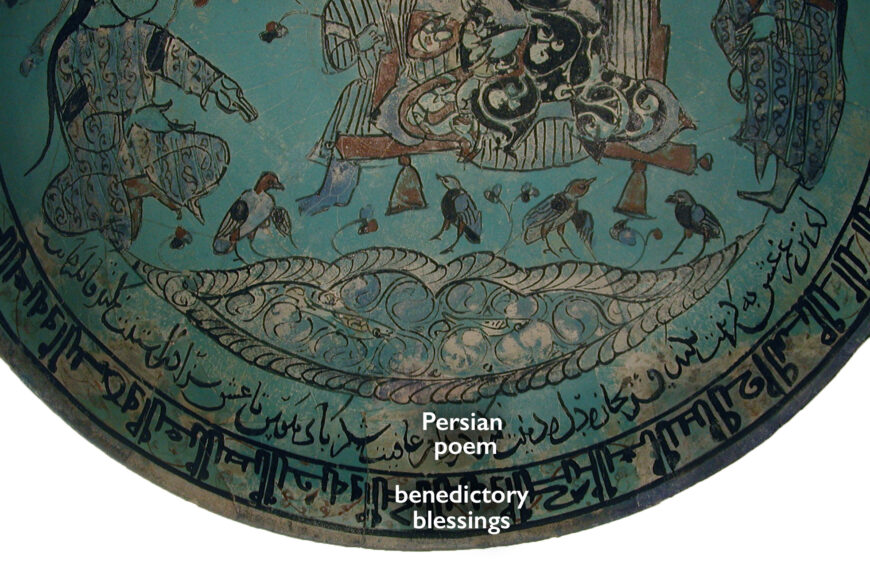

Interior inscriptions, Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Reciting at the majlis: Abu Zayd’s minaʾi bowl

As mentioned above, Abu Zayd’s bowl depicts a motif that was popular on Iranian ceramics—the majlis (pl. majalis). Courtiers and social and intellectual elites are known to have enjoyed such contests of poetic recitation, often accompanied by other forms of entertainment, including feasting and music.

Verses from poems in Persian or Arabic, benedictions for the owner of a vessel, and on occasion the signature and date of the artist, often adorned 12th-century Iranian minaʾi and lusterware vessels. However, they rarely explained the meaning of the depicted scene. This bowl includes two Persian poems written in naskh script on the interior and exterior, respectively, of the bowl:

Oh body, the sorrow of love will not make you any better (than this)

Will not (help)… your soul and faith

At the end, the sweetness of lust will entrap you

So that love will not make a fool of youOh beloved, did you see what the snow (white hair) did to me?

Oh snow (white hair), you told me, but tell my beloved

To the passion (fire) of lovers… and cold (?)

And you are still flirting with me! [2]

Neither of these two poems refer specifically to the events depicted in the bowl. However, in this case, they evoke the setting of the majlis, giving voice to the depicted orator as he recites love poetry. By extension, the owner of the bowl could participate in the majlis by reciting the verses aloud themselves. Perhaps these verses took part in a further intellectual game, where the individual reading the poems could display their intellectual prowess if they could correctly identify the author of the inscribed verses (most of whom were not mentioned by name).

Around the rim of the bowl is yet another inscription, benedictory blessings, or good wishes such as “eternal glory, happiness, victory, and grace,” written in kufic script. [3] Some benedictory inscriptions were addressed directly to the owner, further suggesting that these inscriptions (as well as the poetry) were meant to be read aloud by their owners. In this bowl, Abu Zayd concluded his signature on the exterior of the bowl, writing “long life to its owner and to its writer,” thus invoking the owner of the vessel. Text and image combine together to enliven the majlis scene and engage the viewer in recitation.

Persian poem followed by Abu Zayd’s signature, Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Its reciter and its writer is Abu Zayd”—Abu Zayd and authorship

On its interior and exterior, Abu Zayd prominently signed the bowl, indicating that he not only created the vessel itself, but also composed at least one of the bowl’s poems. While today we may separate the arts of poetry and ceramics, Abu Zayd’s signatures and his compositions speak to their interrelation in 12th-century Iran. On the interior of the vessel, following the Persian poem, he wrote in Arabic, “I recited it and I wrote it,” and on the exterior he wrote in Arabic:

Its reciter (qaʾil) and its writer (katib) is Abu Zayd after he made it.

[This] was written on Wednesday the fourth of Muharram of the year five hundred and eighty-two of the Arab Hijra [1186 C.E.]. Long life to its owner and to its writer.

In both, Abu Zayd emphasizes his authorship as going hand in hand with his skills in the ceramic industry. Not only does he claim the oral poem, by calling himself the reciter, but he also takes ownership of its written manifestation on the bowl by describing himself as the writer. In this case, these roles appear to take precedence over the ceramic craft, which is only referred to once. However, on other vessels, Abu Zayd specifies that he made and decorated the work, claiming artistic ownership as well as giving us insight into the division of labor in the ceramic industry. Abu Zayd’s ceramics reveal the distinctive combination of literary and visual worlds in 12th-century Iranian ceramics.

While not every ceramicist was a poet like Abu Zayd, it is possible that many ceramicists themselves engaged in the sophisticated literary culture of the time. With so many ceramic objects inscribed with poetic quatrains and other verses, it seems likely that the verses themselves were recited aloud in the ceramic workshop from an anthology by one ceramicist while another inscribed them on the vessels. [4]

Abu Zayd died some time after 1220, but his poetry continued to be invoked into the late 13th century. Like so many of the poems he inscribed on his own vessels, his poems eventually became divorced from his name, but were remembered orally and repeated without attribution on luster-painted bowls and tiles well into the late 13th century. [5] As an artist, scribe, and poet, Abu Zayd and his ceramics left an indelible impact on the literary and visual arts of Iran in the 12th century and beyond.