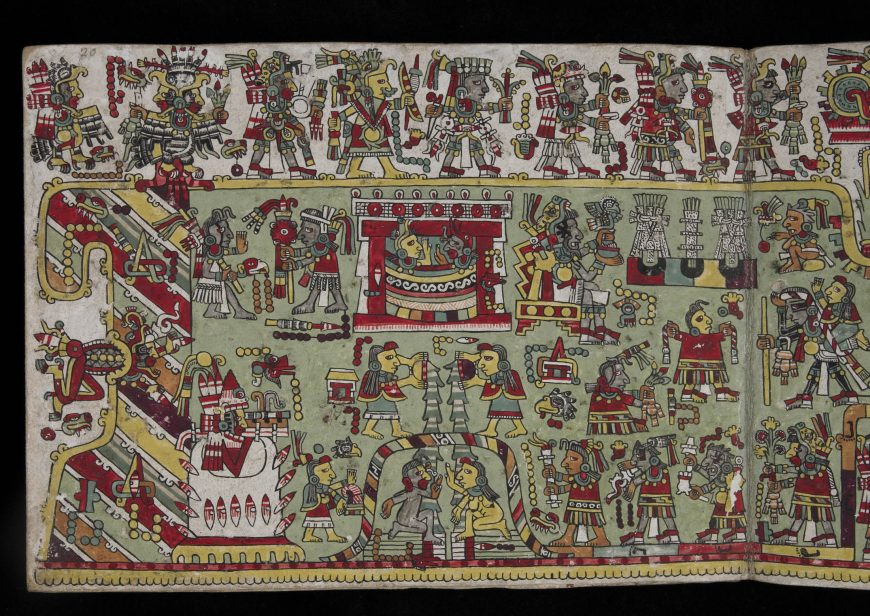

Page from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 1200–1521 C.E., Mixtec, painted deer skin, 19 x 23.5 cm (photo: The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The power of red

Once there was a color so valuable that emperors and conquistadors coveted it, and so did kings and cardinals. Artists went wild over it. Pirates ransacked ships for it. Poets from Donne to Dickinson sang its praises. Scientists vied with each other to probe its mysteries. Desperate men even risked their lives to obtain it. This highly prized commodity was the secret to the color of desire—a tiny dried insect that produced the perfect red.

How could a color be so valuable? In culture after culture, red commands the eye. We are drawn to its power, and to its passion, its sacrifice, its rage, its vitality. It’s not an accident that this coveted color is red: It turns out that we humans are unusually susceptible to scarlet hues. Studies show that the color quickens our pulse and breath, perhaps because we link it with birth, blood, fire, sex, and death.

The quest for a color

But for much of human existence, broad mastery of the color crimson was elusive. Only a few natural substances produce red dye. Henna, madder roots, brazilwood, archil lichens, and fermented stews of rancid olive oil, cow dung, and blood numbered among the sources over the centuries, but most of them fell short—faltering as dyes for textiles and setting into corals, russets, and persimmons instead of true scarlets. The worst of them faded fast into dull pinkish browns. True reds proved rare, and the evocative pigment became even more prized.

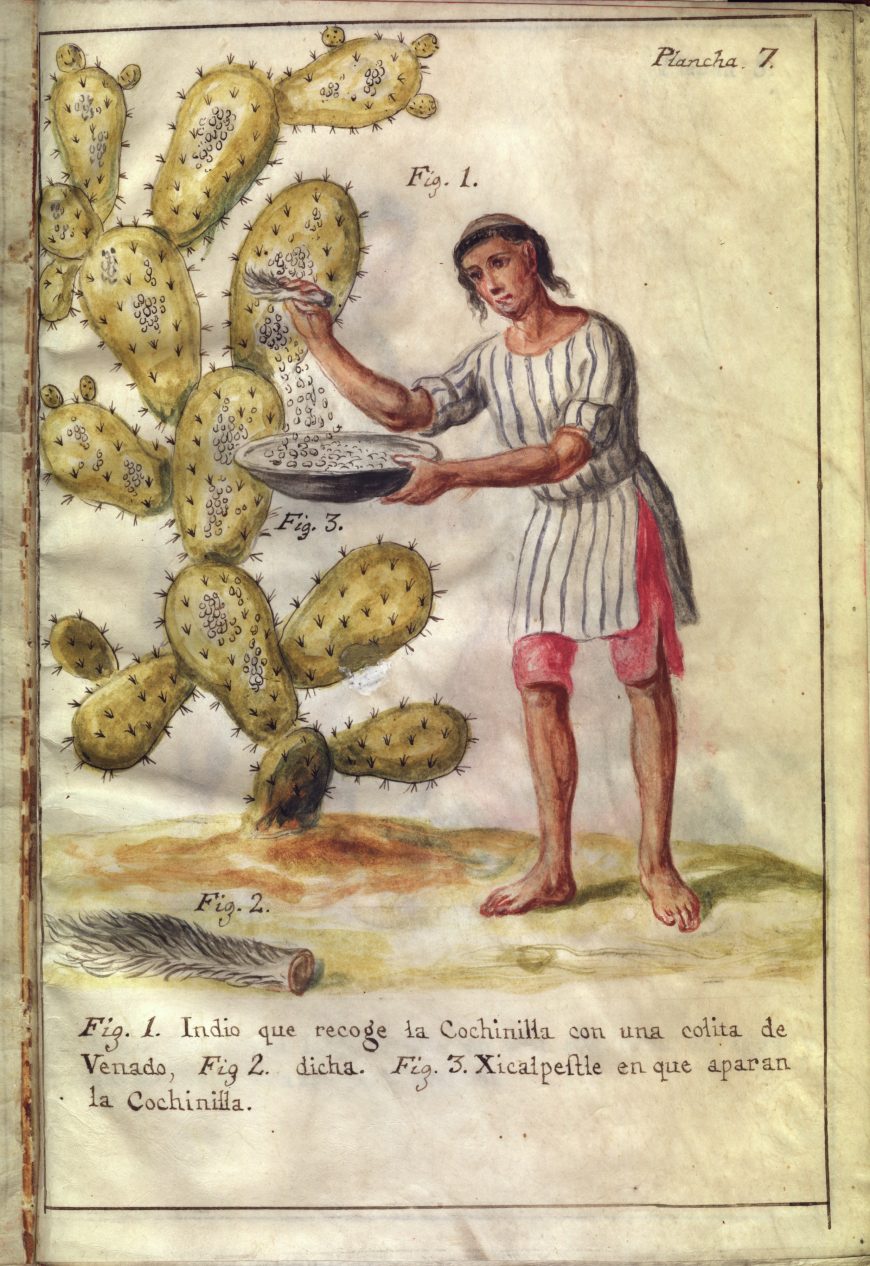

Thousands of years ago, however, Mesoamericans discovered that pinching an insect found on prickly pear cacti yielded a blood-red stain on fingers and fabric. The tiny creature—a parasitic scale insect known as cochineal—was transformed into a precious commodity. Breeders in Mexico’s southern highlands began cultivating cochineal, selecting for both quality and color over many generations.

The results were spectacular. The carminic acid in female cochineals could be used to create a dazzling spectrum of reds, from soft rose to gleaming scarlet to deepest burgundy. Though it took as many as 70,000 dried insects to make a pound of dye, they surpassed all other alternatives in potency and versatility.

Illustration of cochineal collection in José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez, Memoria sobre la naturaleza, cultivo, y beneficio de la grana…, (Essay on the Nature, Cultivation, and Benefits of the Cochineal Insect), 1777, colored pigment on vellum (photo: Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Collection, VAULT Ayer MS 1031).

Cochineal spread through ancient Mexico and Central America, where it was used for the quotidian and the sacred. Textiles, furs, feathers, baskets, pots, medicines, skin, teeth, and even houses bore the brilliant red dye. Scribes colored the history of their people with its crimson ink.

Cochineal comes to the world

When the Spanish conquistadors landed in Mexico, they were struck by the stunning scarlets of the New World. The exotic source of the dye became a sensation back in Europe, where it was deemed the “perfect red.” The Spanish would go on to ship tons of the dried insects back to the Old World and beyond. Their monopoly on the color’s source made it one of their most valuable exports from Mexico, second only to silver.

Dried cochineal insects (photo: H. Zell, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Europeans largely used cochineal on textiles, where it produced red fabrics of an unmatchable sheen and intensity. (It could also be used to make shades of peach, pink, purple, and black—but the reds were what made cochineal famous.) To see this magnificent red was to see power. Court gowns and royal robes were made with cochineal, as were the uniforms of British officers. The scarlet dye even found its way back across the ocean, into the “broad stripes” of the embattled banner over Fort McHenry that inspired the U.S. national anthem.

Original “Star-Spangled Banner” seen by Francis Scott Key (photo: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Painting and pitfalls with the new red

Cochineal also found a spot in the artist’s paint box. If you were a European artist on a tight budget, you could procure your cochineal from shreds of dyed cloth, but fresh-ground insects yielded much better results. Artists usually combined their cochineal with a binder, creating a pigment known as a lake.

It’s impossible to tell with the naked eye which painters used cochineal to make their reds. But recent advances in chemical analysis have confirmed its presence in numerous masterpieces. Among those works is Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of a couple as Isaac and Rebecca, known as The Jewish Bride, about 1665–69, oil on canvas, 121.5 × w 166.5 cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Between the muted browns and golds, the bride’s red gown draws the eye. A combination of vermilion base and cochineal glaze allowed Rembrandt to give the dress its great depth and luster. Other painters of the period also loved to use cochineal lakes to paint glowing red fabrics, such as the shimmering scarlet silks in Anthony van Dyck’s Charity and possibly in the Portrait of Agostino Pallavicini as well.

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Agostino Pallavicini, c. 1621, oil on canvas, 85 1/8 × 55 1/2 inches (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Eye-catching though these cochineal lakes were, they had one great drawback. Unlike cochineal dye on cloth, which usually holds fast to its color, cochineal pigments in paint tended to fade with exposure to light. This was especially true of watercolors. J. M W. Turner’s cochineal-reddened sunsets, for example, literally pale in comparison to what he originally set down.

Cochineal could be fugitive in oils too. A lake made with minimal cochineal, or cochineal of poor quality, faded in a matter of years. Even quality cochineal has dimmed over the centuries. The dowdy jacket in Thomas Gainsborough’s Dr. Ralph Schomberg and the blotchy pastel backdrop of Renoir’s Madame Léon Clapisson both are pale versions of the original.

Thomas Gainsborough, Dr. Ralph Schomberg, c. 1770, oil on canvas, 233 x 153.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Yet while Dr. Schomberg is consigned to his discolored suit for the foreseeable future, Madame Clapisson recently was given new life. A team at Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago analyzed the cochineal that remained in the portrait and digitally recreated the painting in all its glory. Regard the original and the restoration, and you can see both the force of cochineal and its weakness.

When new artificial reds like alizarins made from coal tar became available in the late 19th century—ones more lasting and less expensive than those created by the naturally occurring insect—artists eagerly picked them up. By the late 20th century, artists had abandoned cochineal. Dyers, too, turned to cheaper alternatives. Even in its homeland, the insect nearly disappeared.

A red reborn

Today, in a surprising turn of history, the cochineal market is booming again—thanks to contemporary demand for safe food and cosmetic coloring. See names like carmine, carminic acid, crimson lake, Natural Red 4, or E120 on a label, and you may be looking at a modern manifestation of the color once fit for kings.

A few artists and dyers, too, have been tempted back by its revival—drawn to its intensity and sheen, its historical and cultural resonances. One is Elena Osterwalder, whose stunning installations employ both cochineal and the amatl bark-paper used by Mesoamericans before the Conquest.

In Oaxaca, once the epicenter of the cochineal trade, you can still find traditional weavers breathing new life into the ancient color.

Though the high era of cochineal may have ended, the power conveyed by its potent hue remains. Over centuries and continents, we humans have always been drawn in by red. After all, it’s in our blood.

This essay first appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0).