Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, 1991, Third Avenue and East 137th Street, Bronx, New York. 1 of 24 outdoor billboard locations throughout the New York City area, with 1 indoor location, as part of the exhibition Projects 34: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1992 (The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation; photo: Peter Muscato) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) is a stark, black-and-white image of the rumpled sheets and pillows of an unmade bed. The depression in the center of each pillow, suggesting a recent presence, conveys a profound sense of intimacy. But this scenario is in jarring contrast to its public location—on a billboard. First exhibited on the streets of Manhattan, this evocation of absent bodies soon came to define all of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work up until his death in 1996 from AIDS-related causes. The artist is most known for ephemeral installations: a pile of candy in a corner, a stack of posters on the floor, or strings of lights dangling from a ceiling—all of which recall the reduced visual and formal language of Conceptual and Minimalist art from the 1960s and 1970s.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991; background: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Loverboy), 1989. Installed in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai (The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation; photo: Yan Tao) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm), 1992. Installed in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall (The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Yet Gonzalez-Torres didn’t merely reference the work of earlier Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Dan Flavin—he introduced a specifically contemporary note into his work. In the late 1980s and early 1990s artists were asking new questions around the construction of identity—including gay identity. For instance, the lights in his work were redolent of the environment of a dance club, and the candy on the floor was a perverse reference to the drug AZT used to combat HIV. And the bed? Much like the paired wall clocks he created the same year entitled Perfect Lovers that marched slightly out of step with one another (one is a few seconds off), the censored image of same-sex love slowly makes its imprint.

Bed’s sexual politics

By 1987, a new era of gay activism had begun. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACTUP) formed and suddenly old questions around the relationship between art and politics took on new significance for gay artists. Artist-collectives like Gran Fury used appropriated image and text to convey overt political messages around the politics of AIDS. But Gonzalez-Torres did not follow this route. His disappearing but perpetually replenished works (viewers were allowed to remove a poster or take a piece of candy) took a more elegiac path: it was one in which any direct representation of homosexuality was seldom apparent. Thus his art became an abstract memorialization of loss. Gonzalez-Torres’ memorialization resonated especially during a time when Ronald Reagan (U.S. President from 1981 until 1989) notoriously never uttered the word “AIDS” because of its predominant association with homosexuality. Heads pressed onto pillows in the Untitled billboard thus becomes a simultaneous declaration and disavowal of same-sex love—writ large within an urban landscape.

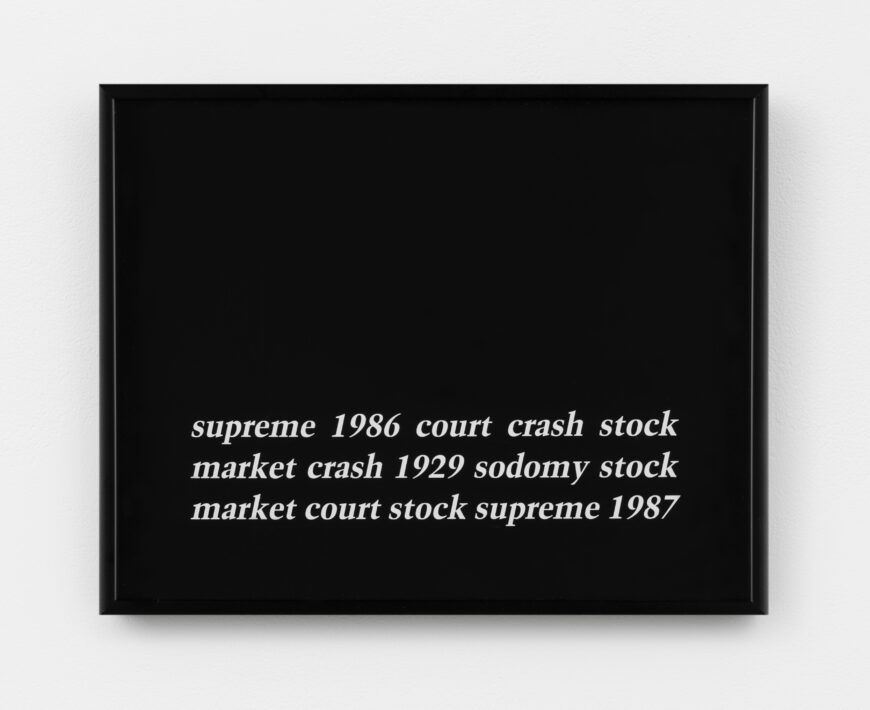

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, 1988, photostat (The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

As an artist, Gonzalez-Torres came of age during the 1980s (he was born in 1957 in Cuba). At that time, postmodern artists often worked with existing imagery and text, appropriating and examining an increasingly media-saturated world. His earliest work was in that vein. In the manner of Jenny Holzer, who reproduced found slogans or random sentiments on wheat-pasted posters throughout the streets of lower Manhattan in the late 1970s, one of Gonzalez-Torres’ earliest works is a framed photostat (an early version of a photocopy) from 1988 of a sentence. It’s really a jumble of words—white letters on a black background that read “supreme 1986 court crash stock market crash 1929 sodomy stock market crash supreme 1987.” In this way, he offered a poetic commentary on the erasure of gay history by sandwiching a reference to the 1986 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the state of Georgia’s sodomy laws (which effectively criminalized homosexuality) between significant dates in economic history. [1]

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, 1991, 77–79 Delancey Street/southeast corner Allen Street, Manhattan, New York (The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation; photo: Peter Muscato) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Back to the future

Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) marked an important threshold in contemporary art history. In the late 1980s the art world underwent significant changes. It seemed to many critics at the time that postmodern art existed only to illustrate complex philosophical concepts, while the felt aspects of experience, important for the renewed surge of identity politics (political alliances based on identity, like the women’s movement), were ignored. Foregrounding the bodily dimension of experience, artists like Robert Gober, Kiki Smith, and Jane Alexander created sculptural works with visceral impact. Artists began to return to discarded artistic strategies like narrative, constructed (rather than appropriated) forms—anything that would invoke a sense of the contemporary, lived aspect of everyday experience without mediation. Bodies were often splayed upon the gallery floor or its parts protruded from a wall.

Gonzalez-Torres’ art had, in a sense, a foot in both camps: Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) bore resemblance to the billboards Barbara Kruger had done as early as 1985. Her Surveillance is Your Busywork is one that was unveiled in Minneapolis that year and featured her trademark use of advertising imagery reconfigured with text to correspond to discussions around public space, gender, and corporate culture. But Gonzalez-Torres’s image of a disheveled bed was shorn of any textual or even didactic directive. Significantly, the image is of his own bed. Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) suggested—even if it did not portray—a tangible if disappearing presence.