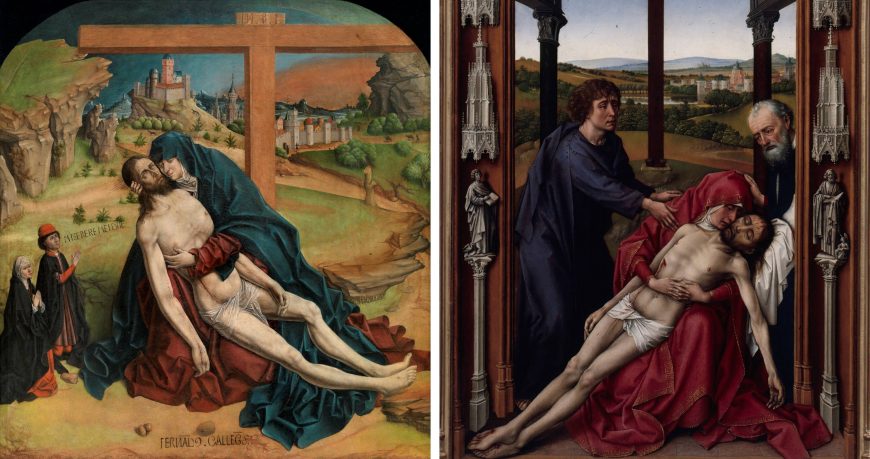

Fernando Gallego, Piedad, 1465–70, mixed method, 118 x 111 cm (Prado Museum)

Mary sorrowfully embraces her dead son, his broken body resting across her lap. The cross rises behind them. In this piedad (often referred to with the Italian word Pietà — an image of Mary cradling the dead body of Christ), painted by the Spanish artist Fernando Gallego, the scene of mourning is set against a vast landscape filled with rocky crags rising from the earth, rolling hills, and a fortified medieval town that is supposed to be Jerusalem in the background. To the left of Mary and Jesus, two smaller figures kneel, most likely the painting’s patrons.

Map of the Kingdoms/Crowns of Spain in 1492 (historians sometimes refer to the larger “kingdoms” that encompass other “kingdoms” as “crowns”)

Trends in Spanish painting: looking to Northern Europe

Gallego was a Spanish artist who worked largely in the Kingdom of Castile in the latter half of the fifteenth century, and his painting is representative of important trends in fifteenth-century Spanish painting. It reveals Gallego’s interest in the Netherlandish (Northern Renaissance) visual idiom, which a great deal of Spanish artists did in the second half of the fifteenth century. His use of realistic details, crumpled drapery, angular bodies, and detailed landscape all parallel Netherlandish artists. Also, Gallego’s treatment of space, especially the empirical perspective we notice throughout the composition, suggests he drew upon northern visual modes.

Left: Fernando Gallego, Piedad, 1465–70, mixed method, 118 x 111 cm (Prado Museum); right: detail, Rogier van der Weyden, Miraflores Altar, c. 1440, 213 x 43 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin)

Gallego likely adapted Rogier van der Weyden’s Pietà from the Miraflores Altar, which had belonged to King Juan II of Castile and then given to the Miraflores Charterhouse (near Burgos). However, Gallego did not slavishly copy van der Weyden’s painting (or another artist’s replica of it) nor Netherlandish painting techniques more generally. His color palette is more distinctly Spanish, with a greater use of yellows and browns. The less saturated and brilliant color palette is due to omitting the glazing so typical of northern painting. Gallego absorbed northern techniques and paired them with his own native ones, and was one of many Spanish artists who found inspiration and models in Netherlandish painting.

An increased internationalization occurred in the second half of the fifteenth century in the Spanish Kingdoms. Trade routes, political exchanges, and merchant activity all helped to foster greater dialogue among artists, among them Lluís Dalmau, Fernando Gallego, Bartolome Bermejo, Jacomart, Jaume Huguet, and Joan Reixac. In particular, many artists across the Spanish Kingdoms began to demonstrate a marked interest in the Netherlandish mode, revealing the influence of the ars nova (the new art — often used to describe the emerging naturalism of Renaissance art) on Spanish art.

In the fifteenth century, the northern European countries we know today as Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg were controlled by the enormously wealthy Dukes of Burgundy (Burgundy is a region in France). This is often referred to, today, as the Burgundian Netherlands.

Bartolomé Bermejo, Saint Michael triumphant over the Devil with the Donor Antoni Joan, 1468, oil and gold on wood, 179.7 x 81.9 cm (National Gallery, London)

Several reasons for this increased interest exist. First, there was a great influx of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and other goods to Spain from Flanders. Such items were collected and displayed in homes or included in prominent collections. The second is the rapid spread of northern woodcuts and engravings, such as those by Martin Schongauer, after 1450. One of the first indications that Netherlandish art was transforming Spanish painting is found in contracts, where we find patrons asking for grisaille to be included in paintings (grisaille, or painting in grayscale, was common in Flanders).

In particular, the Kingdom of Castile and the Kingdom of Aragon borrowed models and styles from their northern counterparts, or had Netherlandish artists travel south to work in the Iberian Peninsula. Until the end of the fifteenth century, there were few classicizing influences and little visual interest in all’antica decoration, such as what we find throughout much of the Italian peninsula.

Trends in the Kingdom/Crown of Aragon

The taste for the Netherlandish visual mode was strong in the second half of the fifteenth century, although it had started earlier. King Alfonso the Magnanimous (King of Aragon, Valencia, Sicily, Majorca, Naples, Corsica, and Sardinia, and Count of Barcelona) displayed an early taste for northern art. In 1434, while in the Kingdom of Sicily, he requested Flemish tapestries from Flanders, and he owned paintings by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

In the Kingdom of Aragon, beginning in the 1440s, painters turned more towards northern influences, moving away from the International Gothic style. Few painters, if any, seemed to travel to Flanders, although it is possible that undiscovered archival records will unearth some. One of the first artists from here who did travel north was Bartolome Bermejo in 1474. Netherlandish artists also settled in the Kingdom of Aragon, although not so many as to suggest they were the ones solely responsible for the popularity of a northern visual idiom.

Valencia and Lluís Dalmau

Lluís Dalmau, Virgin of the Councillors, 1443-1445, oil on oak wood, 316 x 312.5 x 32.5 cm (Museu Nacional d’Art Catalunya)

The Kingdom of Valencia (within the Kingdom/Crown of Aragon) was an especially important place for the Netherlandish visual idiom to take root and grow with Spanish artistic preferences. Some artists traveled north to Flanders. One of the earliest to do so was Lluís Dalmau, who was sent in 1431 by King Alfonso. Born and raised in Valencia, Dalmau had been trained in the International Style. In Flanders, he became acquainted with Netherlandish painting techniques and inventions, and he likely observed well-known artworks like the Ghent Altarpiece in St. Bavo’s Cathedral.

Dalmau returned to Spain, settling in Barcelona. One of the first paintings he completed upon his return was his famous Virgin of the Councillors in Barcelona (Catalonia was at this time part of the Crown of Aragon), which is one of the earliest paintings to exhibit the influences of Netherlandish painting. The painting was commissioned by the Barcelona City Council (Casa de la Ciutat) to hang in the chapel at the council palace.

Detail, Lluís Dalmau, Virgin of the “Consellers”, Lluís Dalmau, 1443-1445, oil on oak wood, 316 x 312.5 x 32.5 cm (Museu Nacional d’Art Catalunya)

It displays the Virgin and Child seated on an elaborate wooden throne, around whom are members of the city council, kneeling before her. Saints and angels stand behind them. Naturalistic details fill the entire painting. The council members are all portraits taken from life, and here they are shown on the same scale as the Virgin Mary. We also observe other characteristics of northern painting, such as elongated bodies and empirical perspective. Dalmau’s painting also clearly indicates the influence of Jan van Eyck, especially his Madonna and Child with Canon van der Paele and the angels from the Ghent Altarpiece in the Adoration of the Lamb panel.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna and Child with Canon van der Paele, 1436, oil on panel, 160 x 124.5 cm (Groeninge Museum Bruges)

Besides Dalmau, other Valencian artists, like Joan Pons and the Master of the Porciùncula, show a keen interest in northern techniques and visual idiom. As we see in the work of Van Eyck and other artists in Northern Europe, paintings are filled with a great deal of ornamentation, including gemstones and brocades.

Northern Renaissance artists also traveled to Spain, producing paintings for important Spanish patrons. Jan van Eyck traveled to the Crown of Aragon in 1427. Many Netherlandish artists would even make careers living and working in Spain. Flemish artists like Luis Alimbrot (Louis Allincbrood or Lodewijk Allyncbrood/Hallincbrood), who was in Bruges 1432–37, was active in Valencia 1439–60. His son, Jordi Alimbrot (Joris Allyncbrood), who was born in and worked in Bruges, also settled and worked in Valencia from 1463 onward.

Not all kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon displayed an early and heightened interest in northern visual modes. Majorca was late to illustrate such influences, only beginning to incorporate them in the 1480s (versus the 1440s in Valencia and 1450s in Catalonia).

The Crown of Castile and the patronage of Isabel of Castile

Netherlandish influence was perhaps strongest in the Kingdom of Castile. However, there is no individual artist, like Dalmau, to whom we credit the origins of such influences. In general, there are fewer named and signed works here, which makes it more challenging to assign this role to a specific artist. Still, we tend to think a Spanish painter with first-hand knowledge of Flemish painting worked in Castile, or perhaps even a Netherlandish artist who relocated there.

Juan de Flandes, The Marriage Feast at Cana, c. 1500–1504, oil on wood, 21 x 15.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Paolo da San Leocadio, Madonna and Child with Saints, 1485, oil on panel, 43.5 x 23.3 cm (National Gallery, London)

By the end of the fifteenth century, many prominent Netherlandish artists lived and worked in Castile, brought there by Queen Isabel of Castile, who adored Netherlandish-style paintings. Michael Sittow, Juan de Flandes, and Antonio Inglés were all foreign artists who came to work for Isabel, who also collected Flemish paintings by Deiric Bouts, Hans Memling, and van der Weyden. Among the immigrant artists at her court, the most famous was Juan de Flandes. He was even made court painter. Concurrently with Isabel’s strong interest in northern influenced artwork, we see other areas of Spain developing an interest in stylistic ideas from the Italian peninsula. While Isabel’s court had a strong interest in Italian humanism and philosophy, it had little interest in its visual aesthetics.

The introduction of Italianizing influences

In the final third of the fifteenth century, especially in Valencia, we begin to see Italian influences. Italian artists also began to arrive and work in Spain, among them Nicola Fiorentino, Francesco Pagano, and Paolo da San Leocadio. These Italianate influences are visible in artworks by Spanish artists like Bermejo. Valencia would become important as a crossroads of Spanish, Netherlandish, and Italian painting. Some have credited the interest in Italian art with the arrival of cardinal Rodrigo de Borja, bishop of Valencia and vice-chancellor of the church of Rome. He came to Valencia accompanied by Paolo da San Leocadio and Francesco Pagano.

The term “Hispano-Flemish”

Paintings like Gallego’s and Dalmau’s are often described as “Hispano-Flemish,” which is intended to highlight their indebtedness to Netherlandish painting though they were painted in Spain with Spanish influences as well. The term is ambiguous though, and for this reason, some people prefer the term “late Gothic” or even “final Gothic,” though these too are somewhat inaccurate. Still others will omit the use of stylistic terminology altogether and simply locate these paintings as being done in the Hispanic Kingdoms between the 1440s and early sixteenth century, and under the influence of Campin, van Eyck, and van der Weyden.