Series of 14 portraits of the Inka Kings, probably mid-18th century, oil on canvas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

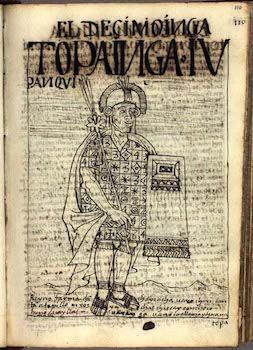

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno (portrait of Tupac Yupanqui, Tenth Inka), 1615

In the Pre-Hispanic period (the period before Spanish colonization) the Inka did not have a tradition of portrait painting comparable to that of Europeans (the Inka Empire was on the west coast of South America, and included parts of present day Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Bolivia). However, following the Spanish Conquest (c. 1534) they quickly appropriated European painting conventions. For example, the images of Sapa Inkas (the sovereign Inka emperors) in Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s famed illustrated chronicle El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government, c. 1615) are among the earliest examples of European-style portraiture executed by an indigenous artist.

Atahualpa, Fourteenth Inka, c. mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 23 ½ x 21 11/16″ (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York)

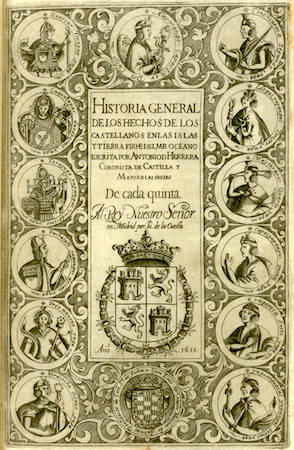

Antonia de Herrera, Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las y tierra firme del mar océano, (fifth decade title page), 1615

The Brooklyn Museum of Art has in its collection a series of fourteen portraits of Inka rulers—one of the portraits depicts the sixteenth-century Inka emperor Atahualpa, dressed in elaborate textiles and wearing golden jewelry. He also holds a royal staff capped with a golden sun, and a golden crown of intertwined snakes rests atop his head.

The Brooklyn series is based on an earlier portrait series which illustrated the Spanish historian and chronicler Antonio Herrera’s Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las islas y tierra firme del mar océano (General History of the Deeds of the Castillians on the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea Known as the West Indies) first published in 1615. General History, a four-volume history of the Americas also known as Décadas, is a descriptive narration of events focused on the experience of the Spanish conquistadors (a term used for a conquering Spanish or Portuguese soldier). The history is divided into eight decades, each of which is introduced by a unique, engraved title page. The title page (left) introducing the fifth decade was the model for the Brooklyn series of Inka rulers.

In both the engraving and the painted series, the figures’ postures and regalia as well as the strategies of representation correspond closely. The Inka kings are shown as half-length figures set in decorative roundels on which are inscribed their names and positions in the line of royal succession. Notably absent from the Herrera engraving is the image of Atahualpa. He is, though, included in the Brooklyn series—with an inscription that reads “bastard tyrant Atahualpa.” The increased scale of his figure in the roundel deviates from the conventions of the other thirteen portraits, such as those of Huayna Capac or Huascar. [1]

Atahualpa and the Spaniards

Right: Huayna Capac, Twelfth Inka, c. mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 21 11/16″ (Brooklyn Museum of Art); left: Huascar, Thirteenth Inka, c. mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 21 11/16″ (Brooklyn Museum of Art)

Atahualpa was the last Sapa Inka before the Spanish Conquest began around 1534. As the inscription on the Brooklyn portrait makes explicit, he was the illegitimate son of Sapa Inka Huayna Capac who died of smallpox in 1528. Although Atahualpa ultimately prevailed in a battle with his elder brother Huascar (born of a different mother) for control of the Inka empire—the timing of the victory was unfortunate. While the civil war raged, the Spanish conquistador Franciso Pizarro, who had landed in present-day Ecuador on his third expedition to the Americas, made his way southward along the western coast of the continent, pillaging and murdering as he traveled. In November of 1523, Atahualpa was celebrating his victory in the city of Cajamarca awaiting the arrival of his prisoner, his brother Huascar. He had learned of Pizarro’s expedition party but believed a retinue of less than two hundred men posed little threat. On November 16 Atahualpa, sumptuously attired, rode into the plaza of Cajamarca atop a luxurious litter (a platform for passengers carried by people) accompanied by high ranking Inka nobles and several thousand guards. He was met by the Dominican friar Vicente de Valverde and an interpreter. After a tense exchange in which Atahualpa threw to the ground a book of Catholic prayers offered to him by Valverde, the friar called out to the Spaniards who had hidden themselves, their mounts and artillery in the buildings surrounding the plaza. Pizarro signaled his men to charge, and in the ambush that followed several thousand Andeans were massacred and Atahualpa was taken prisoner.

In captivity, Atahualpa quickly discovered the Spaniards’ lust for silver and gold. He offered Pizarro an impressive ransom in exchange for his freedom, promising to fill a room approximately 6.2m x 4.8m to half its height (2.5 meters) with gold objects and the same room twice over with silver objects. For the next eight months, gold and silver streamed into Cajamarca from across the empire. Beginning in June the Spaniards began melting down the cache of treasure and divvying up the spoils. After the ransom had been melted and dispersed—and in response to mounting pressure among the expedition party—Pizarro had Atahualpa executed on July 26, 1533, by garroting (a method of execution by which a tightened metal collar results in strangulation).

Who owned this series?

During the colonial period if you visited the home of a powerful cacique (an Indian chieftain or nobleman) you might see royal portraits depicting the succession of Inka kings displayed. Portraits of royal Inka genealogies were especially important in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—these aristocratic genealogies were employed by the Inka elite to assert their privileged social status and claim political power in the viceroyalty. Following the Tupac Amaru II rebellion (1780-81), Inkaist imagery (like depictions of the Sapa Inkas) was banned by Spanish colonial authorities who feared that depictions of aristocratic Inka forbearers as well as contemporary Inka nobility would incite subsequent uprisings. Genealogical Inka portraits, such as the Brooklyn series, would have been seen as subversive in this moment.