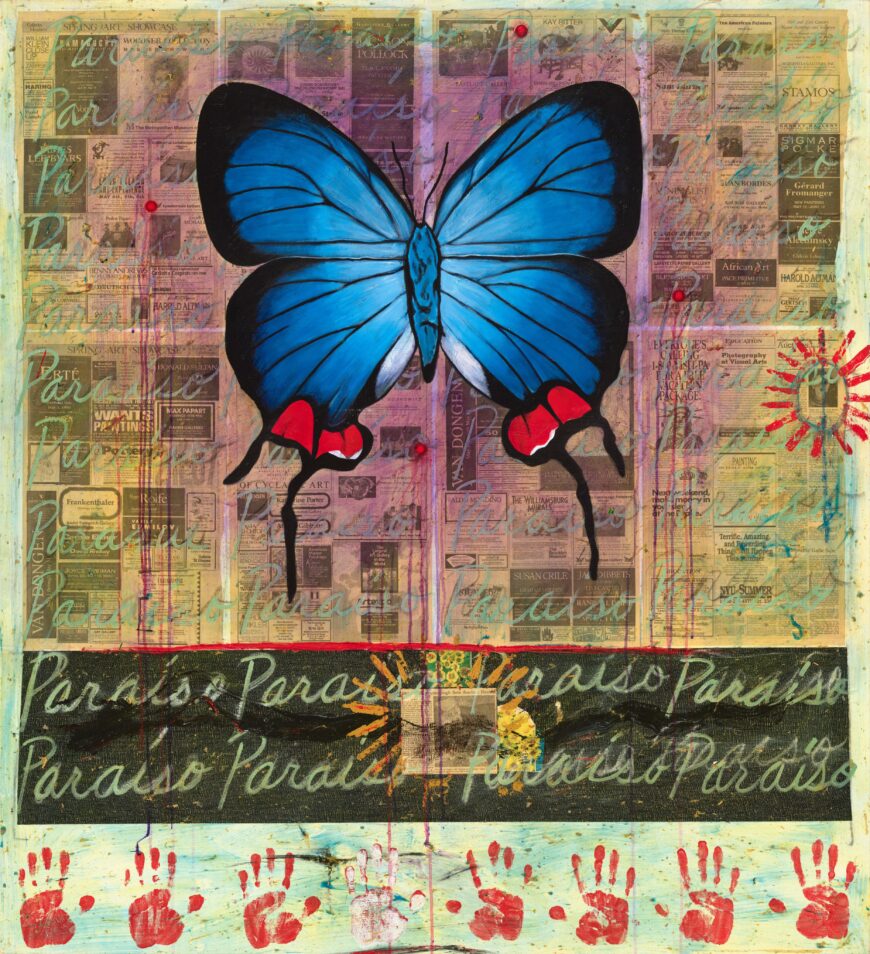

Freddy Rodríguez, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, 1990, acrylic, sawdust, and newspaper collage on canvas, 167.6 x 152.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) © Freddy Rodríguez

A large vibrant and luminescent butterfly with wings outstretched floats atop a collaged background of pages from the arts section of The New York Times. The word paraíso (paradise) repeats in lines down and across the canvas, hand-painted in a delicate blue script. Four circles, painted in bright red, surround the butterfly with paint dripping down, creating the impression of blood-soaked bullet holes. Eight red handprints create a border along the bottom of the canvas. The handprints, four left and four right, evoke bloodied imprints left after a violent crime. The bullet holes and red paint contrast with the brilliance of the butterfly and advertisements for blue chip galleries. Painted by Dominican-born artist Freddy Rodríguez, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure spotlights the violence and trauma that underpins nations like the Dominican Republic and juxtaposes such violence with the exclusionary interests of New York art worlds. The work asks what does it mean to bear witness to violence? How does an artwork encompass the complex layering of trauma and history? How does the New York art world participate in and create its own cycles of economic violence?

The Paraíso series and Rafael Trujillo

Paradise for a Tourist Brochure is part of a series of “Paraíso” paintings begun by Rodríguez in the late 1980s that interrogate the repressive strategies of dictators like Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. Trujillo seized power in 1930 and for thirty-one years he ruled the Dominican Republic with repressive military force, including operating secret police, political assassinations, genocide against Haitians residing in the Dominican Republic, and systematic imprisonment or torture of those who spoke out against his rule. Rodríguez witnessed the impact Trujillo had on the country firsthand and was only sixteen when Trujillo was assassinated in 1961. Following Trujillo’s assassination, Rodríguez participated in leftist student-led protests against Trujillo’s successor Joaquín Balaguer who continued the dictator’s practices of torture and disappearances, activity that led Rodríguez to flee the Dominican Republic for New York City in 1963.

Rodríguez began the Paraíso series nearly thirty years after Trujillo’s assassination, just as headlines across the United States featured the invasion of Panama to depose dictator General Manuel Noriega, and the continued escalation of crises in Central America. Rodríguez links Central America with the Caribbean as two geographical spaces that serve as touristic fantasies seemingly at odds with cycles of social and political violence. With the Paraíso series, Rodríguez confronts Trujillo’s violent legacy and further unpacks the layers of trauma that remain for both himself and the Dominican Republic.

Butterfly (detail), Freddy Rodríguez, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, 1990, acrylic, sawdust, and newspaper collage on canvas, 167.6 x 152.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) © Freddy Rodríguez

The darker side of paradise

In Paradise for a Tourist Brochure a radiant butterfly rises with wings outstretched dominating the top half of the canvas. The butterfly’s wings appear iridescent, with bright white layered atop the blue at the center, getting darker towards the edges. The black lines of the wings form lines from the insect’s center body leading out to the crisp black edge of the wings. The vibrancy of the butterfly and richness of the color contrasts with the sepia tone of the newspapers or the lighter, almost mint color for the repeated lines of “paraíso.” Paradise for a Tourist Brochure uses rich colors to draw viewers in, juxtaposing the beauty of the natural world with violent references. For such fusions of distinct visual and material forms, Rodríguez draws from the combination of subjects and references from Latin American authors such as Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez, both of whom experimented with literary styles to create a range of poetic modes for engaging the political in their work.

Paradise for a Tourist Brochure calls forth the relationship between the natural beauties of the Caribbean and larger conceptions of paradise. The word Paraíso repeats forty-four times throughout Paradise for a Tourist Brochure; however, the script is often barely visible, the light blue fading into the background or the words themselves interrupted by the bullet holes or the butterfly that dominate the image. Rather than a straightforward statement, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure presents paradise as a lingering presence that intersects with the violence punctuating the work.

The repeated word Paraíso that forms lines down the canvas and encompasses the larger series references a letter sent by Columbus to Pope Alexander VI where he describes the New World as an earthly paradise. Such early fantasies of the Caribbean as paradise underpin the centuries of violence that followed throughout colonization and are echoed in the repressive tactics of Trujillo’s dictatorship, and the tourist industry. As Rodríguez later stated, “they transformed it into something that maybe is paradise for tourists that go there for a week, but for the people who live there, including myself … it is a different thing totally.” [1] The vibrant hues and beautiful renderings contrast with the harsh reality of life for many Dominicans. For Rodríguez, the non-human life of the islands, like the butterfly in Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, are more than tourist draws but witnesses to generations of atrocities from Columbus through to the present.

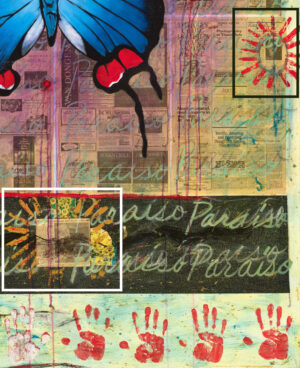

Frida Kahlo and Vincent van Gogh ads (detail), Freddy Rodríguez, Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, 1990, acrylic, sawdust, and newspaper collage on canvas, 167.6 x 152.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) © Freddy Rodríguez

Collage and The New York Times arts section

Pages from the arts section of The New York Times form the base layer of Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, creating an imperfect grid of pages with torn or jagged borders. Rodríguez pulled from issues of the newspaper over the course of weeks between April and May of 1990, showing the range of exhibitions, gallery openings, and advertisements that dominated the New York art world that Spring. While most pages serve as background, in two instances Rodríguez encircled articles detailing recent and upcoming auctions within radiating lines. In one instance, Rodríguez highlights a photograph of Frida Kahlo’s painting Diego and I, by painting a blue oval with rays of red lines expanding outward. The image accompanies an article detailing an upcoming auction of Latin American artists that were expected to reach record prices of up to $9.4 million dollars. Even greater attention and framing is given to an article centered within a thick dark band at the bottom of the canvas. Rodríguez creates a similar border of radiating yellow rays around an article announcing the recent auction of Vincent van Gogh’s painting Portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet, which set a record at $82.5 million. With such framing Rodríguez highlights the disproportionate money and energy devoted to European art in contrast to those by Latin American or African American artists. With Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, Rodríguez further extends his critical eye toward the power of exclusive art worlds that dictate which artistic traditions have value. The juxtaposition of the excessive wealth in the art world within a series on Trujillo’s authoritarian dictatorship implicates the capital exchange of art markets with generations of wealth extraction embedded within colonialism in the Caribbean. Paradise for a Tourist Brochure asks viewers to critically examine the fantasies that mask the violence committed by tourist and art economies.

Each work of the Paraíso series is created with a base of collaged pages from The New York Times combined with handwritten script with colorful paintings of the flora and fauna layered on top. For Rodríguez, the combination of collaged print material with brightly painted images and words encourage viewers to spend more time with the works and unpack the visual references much as they would have with written stories in newspapers. In another work from the series, Símbolo Nacional from 1990, Rodríguez evokes symbols of national power including the flag for the Dominican Republic and the five stars of Trujillo’s military rank. Above the flag Rodríguez wrote “En Esta Casa Trujillo Es el Jefe,” (In This House Trujillo Is the Chief). In another, Los Perros del Paraíso, a list of pseudonyms and names for Trujillo form a list down the right-hand side, with names such as “Dictador,” “El Jefe,” or “General Presidente,” written in thick black cursive. The written text declaring Trujillo’s power reminds viewers of the messages behind Dominican nationalist symbols and their ties to dictatorship. While Paradise for a Tourist Brochure does not include direct references to Trujillo, the use of bright red paint to evoke blood on the palm prints and the bullet holes reminds viewers of the wounds or marks left by his deadly authoritarian practices.

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.