Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The 17th-century papal commission was daunting. It required the winning artist to construct a fountain in the middle of Piazza Navona (a large public open space in Rome) topped with an ancient obelisk that currently lay broken in five pieces two kilometers away. Gian Lorenzo Bernini succeeded in delivering on the almost impossible commission with a heavily sculpted fountain featuring four allegorical river figures, animals, and flora all underneath a vertiginously tall obelisk that still adorns the Piazza Navona to this day. The Baroque monument connected the modern city to its ancient Roman past and proclaimed the triumph of the Pamphili family, whose most famous member Pope Innocent X commissioned the fountain, an act that simultaneously declares the ambitions of the Catholic Church.

Travertine base (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Fountain of the Four Rivers, known as Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in Italian, represents the world in the middle of a circular pool with figures personifying four major rivers from around the globe: the Nile (Africa), Danube (Europe), Ganges (Asia) and Río de la Plata (the Americas). Each figure is accompanied by plants characteristic of its continent e.g., prickly pears for the Americas and a date palm for Africa. [1]

Figures representing the four rivers (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Seven animals—a dolphin, crocodile, lion, horse, serpent, dragon, and sea monster—ring the sculpture. In the center over the travertine base stands the restored “Obelisco Agonale,” an ancient Egyptian granite obelisk likely commissioned by Roman Emperor Domitian in the 1st century C.E. The pope’s crest, the papal tiara, and keys of Saint Peter topping the Pamphili family coat of arms on two sides makes visible the fountain’s patronage.

Pamphili family coat of arms (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Artistically and physically, the monument astounds. Bernini had previously gained acclaim by pushing mediums past what seemed physically possible (see for example, the sculpture Apollo and Daphne). The obelisk rising high in the piazza impresses, but that it should do so held aloft over a travertine base punctuated by multiple cavities astonishes. The bold movement of the figures encourages the spectator to circumambulate the fountain and discover views of the piazza, incredibly, through the stone that holds the obelisk’s weight aloft.

Travertine base (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Career redemption

Bernini’s daring in the design for the Fountain of the Four Rivers occurred when his professional reputation was in tatters. His design for the bell towers at Saint Peter’s Basilica had failed to take into account the unstable ground under Catholicism’s most important church and the towers had cracked. Innocent X canceled the commission and seized Bernini’s assets. [2]

Hendrik Frans van Lint, View of the Piazza Navona, Rome, c. 1730, oil on canvas, 26.7 x 63.5 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Bernini’s position after the disaster at Saint Peter’s was a far cry from the favor he enjoyed under Urban VIII, the previous pontiff. The artist found himself rejected by much of the commissioning class. Innocent X did not invite Bernini to submit a design for the Piazza Navona Fountain. Filippo Baldinucci, Bernini’s 17th-century biographer, describes the artist resorting to subterfuge to place his design in front of the pope. Bernini built a model and asked his friend Prince Niccolò Ludovisi to set it in a room where the pope would see it. When Innocent X stopped to admire the model, only then did Ludovisi inform him who had made it. The Pamphili pope acknowledged the superiority of the design and awarded Bernini the commission.

Figure personifying the Ganges river (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Transformation of the Piazza Navona

The Piazza Navona had been a politically and culturally important public space in Rome since antiquity. Under Emperor Domitian, the oval space had hosted the Stadium of Domitian where athletic competitions were held. In the early modern period since 1477, the square hosted a daily food market. Other items were sold there as well. People collected water from a plain water trough as well as the more elegant Fountain of Neptune and Fountain of the Moor completed by Giacomo della Porta in the 1570s. With his election to the papacy in 1644, Innocent X began a massive refashioning of the Piazza Navona. In addition to the Fountain of the Four Rivers, he commissioned his family palace, the Palazzo Pamphili, and the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone on the square—all within the first decade of his pontificate.

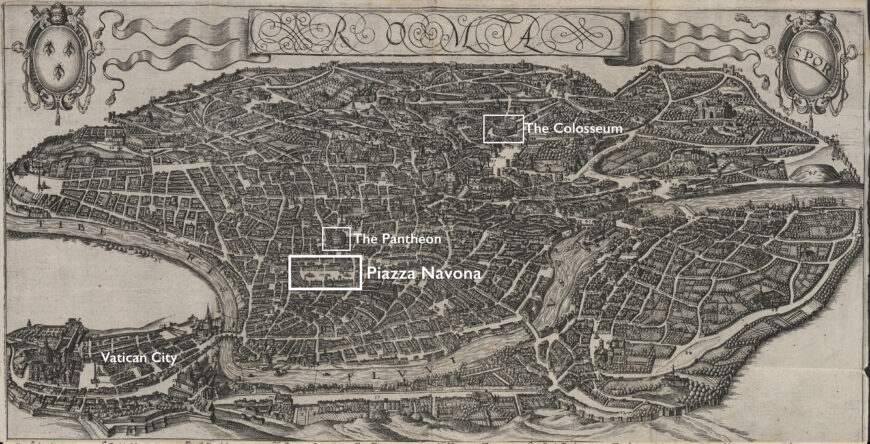

Johann Heinrich von Pflaumern, Roma, etching, 29.2 x 38.1 cm (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich)

Pope Innocent X’s transformation of the Piazza Navona was a significant intervention into the urban fabric of Rome, but was not unusual among papal projects in the 17th century. The pope, as head of the Catholic Church, was also the political leader of the Papal States. Popes, elected by the College of Cardinals, typically selected clergymen from powerful families. Upon election, a pope had broad power to modify the urban landscape in Rome through architectural and infrastructure projects.

The market in Piazza Navona, c. 1625–44, oil on canvas, 101.2 x 135.3 cm (Museo di Roma)

At the Piazza Navona, the public market and water sources had created a helter-skelter space ungoverned by a singular authority. Government attempts to clarify stall ownerships, require licensing for fruit vendors, and collect taxes had been mostly unsuccessful. The square remained unpaved. The Pamphili papacy took control of the square by displacing food sellers, eliminating the market, and destroying housing to build the Palazzo Pamphili. Once Bernini’s fountain was completed, Innocent X declared the square a “place of beauty.” [3] The prominence of the Pamphili dove on the family’s coat of arms also declared the square a Pamphili space. The bustling fullness of foot traffic and exchange of goods was replaced by carriages moving through an architecturally coordinated backdrop for serene upper-class life and urban festivals celebrating the family and Pamphili papacy. [4]

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Papal magnificence

The Fountain of the Four Rivers at Piazza Navona combined symbols and imagery from multiple traditions to argue for the magnificence of both the Catholic papacy and the Pamphili family at a time when the Catholic Church’s power and influenced had waned due to the rise of Protestantism. Meanwhile, Catholic displays of magnificence increased in scale. Bernini himself had contributed the Baldacchino, Cathedra Petri, and colonnaded piazza at Saint Peter’s Basilica.

The Pamphili dove atop the obelisk (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The success of resurrecting and transporting an ancient obelisk across Rome was viewed as a testament to the strength of the Catholic Church and papacy. Innocent X charged the Jesuit Egyptologist Athanasius Kircher with the challenge of transporting the obelisk from the Circus Maximus. His efforts, costing 12,000 scudi, were celebrated in Obeliscus Pamphilius, a heavily illustrated book published in 1650. Since the reign of Sixtus V in the 16th century, popes had appropriated ancient obelisks to stand in Catholic spaces. When Rome conquered Egypt in 30 B.C.E., the empire brought Egyptian obelisks to the capital. Catholic appropriation of the obelisk in turn echoed that ancient conquest—if only symbolically.

Lion (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi), Piazza Navona, Rome, commission by Pope Innocent X, 1651, marble (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Fountain of the Four Rivers assembled symbols into a form communicating global papal power. [5] The obelisk’s single point unifies the four corners of the earth represented by the allegorical river figures, each from a different continent. Early modern scholars including Kircher understood obelisks as symbols of divine light, which aided a Catholic message of sending the “light” of Christianity across the globe. Personified river gods directly recalling ancient Roman sculpture furthered the claim that Catholicism had supplanted empires of the past. The Pamphili fountain declared Catholicism’s realm to be nothing less than the entire world and that the religion was conqueror as well as heir to history’s great civilizations.