Just how did Gothic architects support heavy stone ceilings and create the effect of heaven on earth?

A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in Beverley Minster, England, 1190–1420

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in Beverley Minster in Beverley, England. We wanted to talk about the basic elements of a Gothic church.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] Probably the most basic element that identifies the Gothic style is the use of a pointed — not a round, a pointed — arch.

Dr. Zucker: [0:23] The pointed arch was a Gothic innovation that allowed Gothic architects to do what they really wanted to do, which was to build larger and brighter churches.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] Light was associated with God, with the divine.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] It’s a perfect metaphor. Light has an almost magical quality in that it can pass through a solid. It can pass through glass.

Dr. Harris: [0:47] Romanesque churches, just before the Gothic period, required large, thick expanses of wall to hold up the ceiling. Usually a barrel-vaulted ceiling. From the rounded barrel vault, the architects moved on to the groin vault.

Dr. Zucker: [1:06] The weight of a round arch pushes outward and requires a lot of buttressing. [A] big, solid wall underneath. The pointed arch redirects its weight more directly downward so that the supports can be thinner and can be more delicate. The Gothic architects brilliantly realized that that innovation would allow them to be able to have less wall and more window.

Dr. Harris: [1:31] The weight of the vault didn’t need to come down onto continuous walls, but could come down onto four columns. Opening up not just the walls to windows, but opening up the very space of the church itself.

Dr. Zucker: [1:45] We might ask, then, how is the stone vaulting held up? The answer can be found in two places. First, if you look in between the glass, you can see a major structural element, which comes down to the nave level in the form of a pier. Now, Gothic architects camouflaged the massiveness of their piers by ornamenting them with delicate, thin colonnettes.

[2:11] This was a massive object that helps to support the stone vaulting above. But there’s another structural system that’s at work. Even with the pointed arch, the vaulting of these churches still created lateral thrust that pushed outward. And so the building had to be contained. It had to be supported from the outside. It had to be buttressed.

Dr. Harris: [2:33] That’s where we see one of the great features of Gothic architecture, the flying buttress; essentially a bracing in between the windows on the outside of the church.

Dr. Zucker: [2:46] Because they are relatively delicate and pierced, they allow light to get to the windows, to flood the interior with brightness.

Dr. Harris: [2:54] When we look up along the wall of a typical Gothic church, we usually see three parts. We see the pointed arches that form the nave arcade. We see above that the triforium, and above that the clerestory, the level with windows.

[3:12] When we look at [a] triforium, even there we see the wall is pierced. Here in Beverley Minster, we see trefoil-shaped arches. Within that trefoiled arch, we see a quatrefoil, and then below that yet another level of opening, of these short, pointed arches that are separated by columns. This layering that allows the wall to have sense of depth.

Dr. Zucker: [3:40] All of this brings our eye upward. It emphasizes the heavenly. The intent of the Gothic church is to create a sense of the heavenly on earth.

Dr. Harris: [3:51] If you imagine a typical person’s home in the 13th century, we imagine something dark and without a lot of windows, so coming into a space like this must have seemed truly miraculous.

[4:05] It’s even difficult, I think, for us in the 21st century to imagine the workmanship, the decades of labor, and the enormous costs that went into these buildings as places of worship, of places of connection to the divine.

[4:22] [music]

East end of Salisbury Cathedral.

Forget the association of the word “Gothic” to dark, haunted houses, Wuthering Heights, or ghostly pale people wearing black nail polish and ripped fishnets. The original Gothic style was actually developed to bring sunshine into people’s lives, and especially into their churches. To get past the accrued definitions of the centuries, it’s best to go back to the very start of the word Gothic, and to the style that bears the name.

The Goths were a so-called barbaric tribe who held power in various regions of Europe, between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire (so, from roughly the fifth to the eighth century). As with many art historical terms, “Gothic” came to be applied to a certain architectural style after the fact.

Early Gothic arches, Southwell Minster.

The style represented giant steps away from the previous, relatively basic building systems that had prevailed. The Gothic grew out of the Romanesque architectural style, when both prosperity and relative peace allowed for several centuries of cultural development and great building schemes. From roughly 1000 to 1400, several significant cathedrals and churches were built, particularly in Britain and France, offering architects and masons a chance to work out ever more complex and daring designs.

The most fundamental element of the Gothic style of architecture is the pointed arch, which was likely borrowed from Islamic architecture that would have been seen in Spain at this time. The pointed arch relieved some of the thrust, and therefore, the stress on other structural elements. It then became possible to reduce the size of the columns or piers that supported the arch.

Nave of Salisbury Cathedral.

So, rather than having massive, drum-like columns as in the Romanesque churches, the new columns could be more slender. This slimness was repeated in the upper levels of the nave, so that the gallery and clerestory would not seem to overpower the lower arcade. In fact, the column basically continued all the way to the roof, and became part of the vault.

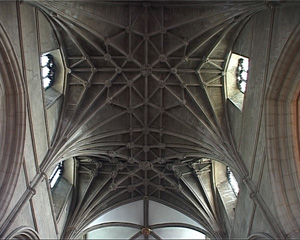

In the vault, the pointed arch could be seen in three dimensions where the ribbed vaulting met in the center of the ceiling of each bay. This ribbed vaulting is another distinguishing feature of Gothic architecture. However, it should be noted that prototypes for the pointed arches and ribbed vaulting were seen first in late-Romanesque buildings.

Open tracery at Southwell Minster.

The new understanding of architecture and design led to more fantastic examples of vaulting and ornamentation, and the Early Gothic or Lancet style (from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) developed into the Decorated or Rayonnant Gothic (roughly fourteenth century). The ornate stonework that held the windows–called tracery–became more florid, and other stonework even more exuberant.

The ribbed vaulting became more complicated and was crossed with lierne ribs into complex webs, or the addition of cross ribs, called tierceron. As the decoration developed further, the Perpendicular or International Gothic took over (fifteenth century). Fan vaulting decorated half-conoid shapes extending from the tops of the columnar ribs.

Lierne vaults Gloucester Cathedral.

The slender columns and lighter systems of thrust allowed for larger windows and more light. The windows, tracery, carvings, and ribs make up a dizzying display of decoration that one encounters in a Gothic church. In late Gothic buildings, almost every surface is decorated. Although such a building as a whole is ordered and coherent, the profusion of shapes and patterns can make a sense of order difficult to discern at first glance.

Gothic windows at Gloucester Cathedral.

After the great flowering of Gothic style, tastes again shifted back to the neat, straight lines and rational geometry of the Classical era. It was in the Renaissance that the name Gothic came to be applied to this medieval style that seemed vulgar to Renaissance sensibilities. It is still the term we use today, though hopefully without the implied insult, which negates the amazing leaps of imagination and engineering that were required to build such edifices.