Francisco Goya, And there’s nothing to be done (Y no hai remedio), plate 15 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), 1810, etching, drypoint, burin and burnisher, 14 x 16.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

And there’s nothing to be done

A man, blind-folded, head downcast, stands bound to a wooden pole. His white clothes, despite tears and rips, seem to emit light; although the man’s off-kilter posture signifies defeat, he is yet heroic, an Alter Christus—another Christ. On the ground in front of him is a corpse, contorted, the spine twisted, arms and legs sprawled in opposite directions. His grotesque face looks out at us through obscured eyes as blood and brain matter ooze out of his skull and pool around his head. Seconds ago this man was alive. Further off, to our hero’s left, other men, doubled-over and on their knees, are similarly secured to wooden stakes. To his right we see the cause of the carnage: a neat line of soldiers aim rifles at the men, the muzzle of their weapons disappearing behind our hero’s hip. But the rest of the gun is not left to our imagination. Suddenly—and in such an obvious position that we wonder how we did not see them before—the barrel of three rifles appear from the right edge of the picture, aimed at our messianic hero. Not only is he about to die, but his executioners are everywhere. As the caption of the picture tells us, “Y no hay remedio” (And there’s nothing to be done).

Dead figure (detail), Francisco Goya, And there’s nothing to be done (Y no hai remedio), plate 15 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), 1810, etching, drypoint, burin and burnisher, 14 x 16.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Francisco Goya created the aquatint series The Disasters of War from 1810 to 1820. The eighty-two images add up to a visual indictment of and protest against the French occupation of Spain by Napoleon Bonaparte. The French Emperor had seized control of the country in 1807 after he tricked the king of Spain, Charles IV, into allowing Napoleon’s troops to pass its border, under the pretext of helping Charles invade Portugal. He did not. Instead, he usurped the throne and installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as ruler of Spain. Soon, a bloody uprising, occurred, in which countless Spaniards were slaughtered in Spain’s cities and countryside. Although Spain eventually expelled the French in 1814 following the Peninsular War (1807-1814), the military conflict was a long and gruesome ordeal for both nations. Throughout the entire time, Goya worked as a court artist for Joseph Bonaparte, though he would later deny any involvement with the French “intruder king.”

Process

Goya created his Disasters of War series by using the techniques of etching and drypoint. Goya was able to use this technique to create nuanced shades of light and dark that capture the powerful emotional intensity of the horrific scenes in the Disasters of War.

The first step was to etch the plate. This was done by covering a copper plate with wax and then scratching lines into the wax with a stylus (a sharp needle-like implement) thus exposed the metal. The plate was then placed in an acid bath. The acid bit into the metal where it was exposed (the rest of the plate was protected by the wax). Next the acid was washed from the plate and the plate was heated so the wax softened and could be wiped away. The plate then had soft, even, recessed lines etched by the acid where Goya had drawn into the wax.

The next step, drypoint, created lines by a different method. Here Goya scratched directly into the surface of the plate with a stylus. This resulted in a less even line since each scratch left a small ragged ridge on either side of the line. These minute ridges catch the ink and create a soft distinctive line when printed. However, because these ridges are delicate and are crushed by repeatedly being run through a press, the earliest prints in a series are generally more highly valued.

Finally, the artist inked the plate and wiped away any excess so that ink remained only in the areas where the acid bit into the metal plate or where the stylus had scratched the surface. The plate and moist paper were then placed atop one another and run through a press. The paper, now a print, drew the ink from the metal, and became a mirror of the plate.

Bound figure and soldiers (detail), Francisco Goya, And there’s nothing to be done (Y no hai remedio), plate 15 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), 1810, etching, drypoint, burin and burnisher, 14 x 16.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

War as disaster

The first group of prints, to which “Y no hay remedio” belongs, shows the sobering consequences of conflict between French troops and Spanish civilians. The second group documents the effects of a famine that hit Spain in 1811-1812, at the end of French rule. The final set of pictures depicts the disappointment and demoralization of the Spanish rebels, who, after finally defeating the French, found that their reinstated monarchy would not accept any political reforms. Although they had expelled Bonaparte, the throne of Spain was still occupied by a tyrant. And this time, they had fought to put him there.

Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 266 x 345.1 cm (Prado. Madrid)

The Disasters of War were Goya’s second series, made after his earlier Los Caprichos. This set of images was also a critique of the contemporary world, satirizing the socio-economic system in Spain that caused most people to live in poverty and forced them to act immorally just to survive. Goya condemned all levels of society, from prostitutes to clergy. But The Disasters of War was not the last time that Goya would take on the subject of the horrors of the Peninsular War. In 1814, after completing The Disasters of War, Goya created his masterpiece The Third of May, 1808 which portrays the ramifications of the initial uprising of Spanish against the French, right after Napoleon’s takeover. Sometimes called “The first modern painting,” its resemblance to “Y no hai remedio” is undeniable. In this painting, a Christ-like figure stands in front of a firing squad, waiting to die. This line of soldiers is nearly identical to the murderers in the aquatint. In The Third of May, 1808 the number of assassins and victims is countless, indicating, once again, that “there is nothing to be done.” Although it is impossible to say whether the print or the painting came first, the repetition of the imagery is evidence that this theme—the inexorable cruelty of one group of people towards another—was a preoccupation of the artist, whose imagery would only become darker as he became older.

Goya, This is worse (Esto es peor), plate 37 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de La Guerra), 1810, etching, lavish and drypoint, plate: 15.3 x 20.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

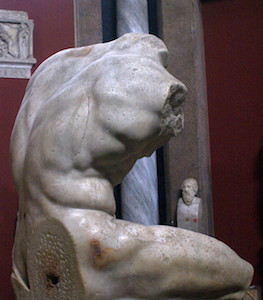

Belvedere Torso, marble copy of a Greek bronze original, probably from the 2nd century B.C.E. (Vatican Museums) (photo: Giovanni, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although “And There’s Nothing to Be Done” may have crystallized the theme of The Disasters of War, it is not the most gruesome. This honor may belong to the print “Esto es peor (This is Worse),” which captures the real-life massacre of Spanish civilians by the French army in 1808. In the macabre image, Goya copied a famous Hellenistic Greek fragment, the Belvedere Torso (left), to create the body of the dead victim. Like the ancient fragment, he is armless, but this is because the French have mutilated his body, which is impaled on a tree through his anus and shoulder. As in “There is Nothing to be Done,” the corpse face stares out at the viewer, who must confront his own culpability in allowing the massacre to take place. “There is Nothing to be Done,” can also be compared to the plate “No se puede mirar (One cannot look),” in which the same faceless line of executioners points their weapons at a group of women and men, who are about to die.

Francisco Goya, One can’t look. (No se puede mirar.), plate 26 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), 1810-20, etching, burnished lavish, drypoint and burin, plate: 14.5 x 21 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Goya’s Disasters of War series was not printed until thirty-five years after the artist’s death, when it was finally safe for the artist’s political views to be known. The images remain shocking today, and even influenced the novel of famous American author Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls, a book about the violence and inhumanity in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Hemingway shared Goya’s belief, expressed in The Disasters of War, that war, even if justified, brings out the inhumane in man, and causes us to act like beasts. And for both artists, the consumer, who examines the dismembered corpses of the aquatints or reads the gruesome descriptions of murder but does nothing to stop the assassin, is complicit in the violence with the murderer.

Additional resources:

Goya, “And there is Nothing to be done” from Art Through Time