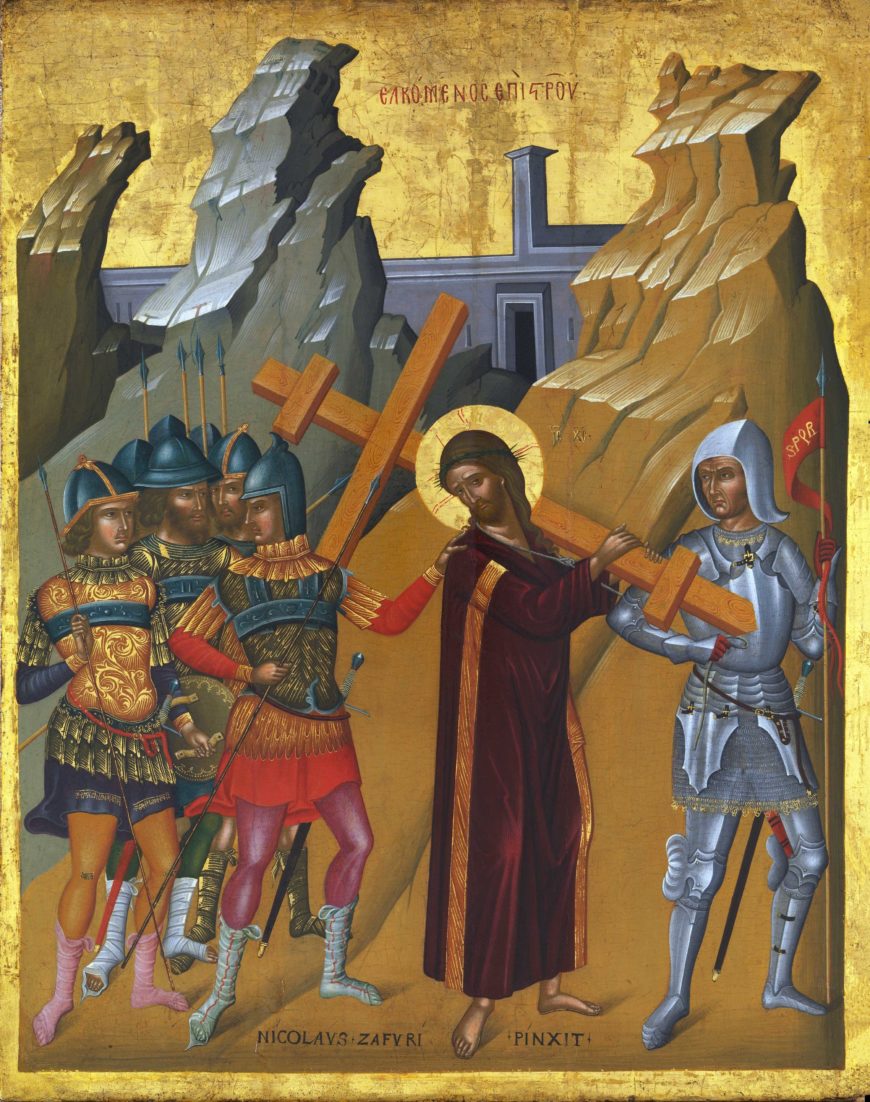

Nicolaos Tzafouris, Christ Bearing the Cross, late 1400s, oil on tempera and gold ground, 69.2 x 54.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Seven Hundred Icons, Two Styles

In 1499 two dealers, one Venetian and the other Greek, placed an order for artists on the island of Crete (then part of the Republic of Venice) to make seven hundred icons of the Madonna and Child. They stipulated that five hundred were to be in the “Latin style” and the rest in the “Greek style.” By exploring further what is meant by Latin and Greek styles, and what their prominence tells us about the artistic environment of Venice, we can understand better the multicultural influences that shaped the Renaissance in Italy.

Byzantine Venice

While other places in renaissance Italy celebrated the heritage of ancient Rome, the art and culture of Venice is equally indebted to its longstanding ties to the Byzantine Empire. This is evidenced by Saint Mark’s Basilica, a church begun in the year 1063 and filled with shimmering Byzantine-style mosaics, altars, and icons. Those ties remained strong in the 1400s and 1500s thanks to the Republic of Venice’s colonization of Greek islands that had been under Byzantine control until the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Most prominent of those was Crete, which came under Venetian control in the early 1200s and remained Venetian until being lost to the Ottoman Empire in 1669. As a result, for the entirety of the Renaissance, Venice had among its territorial possessions an island that retained a culturally and artistically Byzantine character. Artistic exchanges between Venice and Crete at that time contributed to the formation of an artistic environment unique in the Italian renaissance.

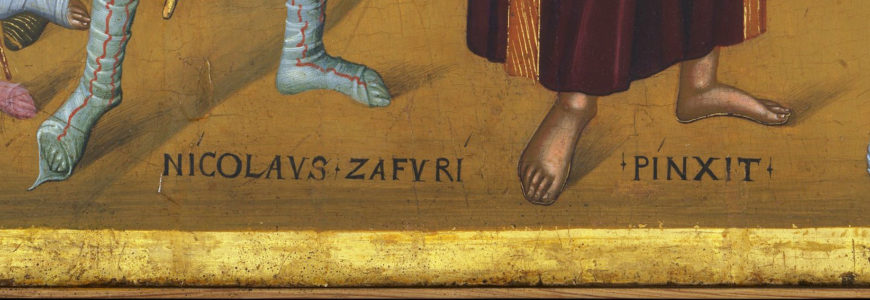

Nicolaos Tzafouris, Christ Bearing the Cross (detail), late 1400s, oil on tempera and gold ground, 69.2 x 54.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Icon Painters in Venetian Crete

The artistic production of Crete during its Venetian period remained heavily influenced by Byzantine art. Consequently, many painters in Venetian Crete worked in what was called the “Greek style” and thus retained traits that we can identify with earlier Byzantine icons.

Left: Nicolaos Tzafouris, Christ Bearing the Cross, late 1400s, oil on tempera and gold ground, 69.2 x 54.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Raphael, Christ Carrying the Cross, c. 1514–17, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 318 x 229 cm (Museo del Prado)

For example, Nicolaos Tzafouris was active in Venetian Crete in the last decades of the 1400s. Characteristic of his work is an icon of Christ Bearing the Cross. The subject, where soldiers lead Christ towards the place of his Crucifixion, is a standard religious narrative. His representation includes a flat gold background; simple, stylized landscape elements; restricted pictorial space; and wispy figure types. These Byzantine traits differ from paintings being made in Italy around the same period in what some called the “Latin style.” For instance, Raphael’s painting of a similar subject privileges a luminous naturalistic setting and lively figures in motion whose bodies appear to have real weight and mass.

NICOLAVS ZAFVRI PINXIT at the bottom of the painting. Nicolaos Tzafouris, Christ Bearing the Cross (detail), late 1400s, oil on tempera and gold ground, 69.2 x 54.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Significantly, Tzafouris signed his name at the bottom of his icon in Latin “NICOLAVS ZAFVRI PINXIT” (“Nicolaos Tzafouris painted it”). This could signify that his icon, despite its many references to the “Greek style” of painting, was destined for a Venetian (not Cretan) client. Indeed, Crete gave Venice a direct line of access to artists, like Tzafouris, working in a style that differed from the advancements in pictorial and anatomical naturalism that proliferated in Venice and elsewhere in renaissance Italy. This created an artistic culture that was far more mixed than what is evident when one only looks at paintings by the famous renaissance artists Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and Tintoretto that often have more elaborate figures, detailed naturalistic backgrounds, and displays of light and color based on natural observation.

Michael Damaskinos, Last Supper, c. 1585–91, St. Catherine’s monastery, Herakleion, Crete (photo: C messier, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Greeks in Venice

Some Cretan painters traveled to Venice in the sixteenth century and joined the thriving community of immigrants organized around the Scuola dei Greci (Confraternity of Greeks) . Prominent among them was Michael Damaskinos, who was in Venice for part of the 1570s and 1580s before returning to Crete.

Iconostasis, San Giorgio dei Greci, Venice (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Along with other Cretan painters, he contributed images to the iconostasis at the Greek church of San Giorgio dei Greci (Saint George of the Greeks) in a style of painting that mixed Byzantine and Italian renaissance features.

Michael Damaskinos, Last Supper (detail), c. 1585–91, St. Catherine’s monastery, Herakleion, Crete (photo: C messier, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Indeed, many of his icons, such as his Last Supper, blend traditional Greek styles with influences from Italian artists. While he often keeps gold backgrounds, stylized treatments of drapery whose folds appear more regular and patterned than naturalistic, and Greek inscriptions, Damaskinos often reveals significant departures from the largely Byzantine heritage of Nicolaos Tzafouris by showing classical (ancient Greek and Roman) architectural elements such as columns and arches, perspectival depth, and figures rendered with volumetric mass moving in space.

El Greco in Italy

The most famous of the Cretan painters who traveled to Venice was Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known today as El Greco (“The Greek”). El Greco was born on Crete where he was trained in a mixed style of painting combining Byzantine and Venetian renaissance traits characteristic for artists at that time. El Greco soon migrated westward. By the year 1567 he was in Venice, where he stayed until his departure for Rome around 1570. He would remain in Rome until at least 1576, around the time he left for Toledo, Spain, where he lived until his death in 1614. All along the way El Greco’s style of painting changed suddenly and dramatically.

El Greco, St. Luke Painting the Virgin and Child, c. 1560–67, tempera and oil on panel, 41.6 x 33 cm (Benaki Museum)

His panel showing St. Luke Painting the Icon of the Virgin and Child, painted while still in Crete, mixes Greek (Byzantine) and Latin styles (classicizing Italian and Venetian Renaissance). Saint Luke, while thin and elongated, appears in profile and occupies a defined three-dimensional space. But the icon of the Virgin and Child that he paints is rooted in the Byzantine manner by displaying flat, frontal figures in a stylized or patterned treatment of folded drapery against a gold background.

El Greco, Christ Healing the Blind, ca. 1570, oil on canvas, 119.4 x 146.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

While Tzafouris and Damaskinos maintained a strong adherence to Byzantine styles of painting, El Greco’s Christ Healing the Blind shows how much he wished to paint in a a manner reflective of both the classicizing Italian and Venetian renaissance manner once he arrived in Venice. The subject is one of Christ’s most celebrated miracles, where Christ imparted vision to a man born blind by touching his eyes. All figures, though somewhat scrunched together, are rendered with anatomical precision, clad in billowing drapery, and in animated poses that express their reactions to witnessing this miracle. Instead of the gold background characteristic of many Byzantine and Cretan icons, we see an emphatically and carefully delineated one-point perspective resembling experimental renderings of three-dimensional space that mark many Italian renaissance paintings from the 1400s. One side is populated by buildings replete with round arches and columns conforming to the central Italian renaissance taste for the architecture of Roman antiquity.

Triumphal arch in the background. El Greco, Christ Healing the Blind (detail), ca. 1570, oil on canvas, 119.4 x 146.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Some, such as the round temple on the left and the variation on the triumphal arch in the background, derive from ancient examples that El Greco may have seen in Rome. Further, the influence of renaissance art on him is revealed through rich coloristic effects that resemble the grand narratives by Paolo Veronese, Tintoretto, and Titian.

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi (detail), 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice)

Titian, Christ Crowned with Thorns (detail), c. 1570–76, oil on canvas, 280 x 182 cm (Alte Pinakothek, Munich; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For instance, consider the visual splendor of Veronese’s Feast in the House of Levi, which delights in the full range of rich tones and luminous colors for staging this event. What El Greco adopted from his Venetian peers was a visible fluidity of brushwork. We see this use of thick streaks of paint on the surface of works like Titian’s Christ Crowned with Thorns. In so using this technique, El Greco embraced the leading feature that most differentiated Venetian paintings from the central Italian emphasis on blended brushstrokes, precise outlines, and clearly delineated contours.

El Greco proves that Greek painters were mobile, traversing whatever cultural divides we might think separated the Greek/Byzantine east and the Latin/renaissance west. But what his output also shows is that he was capable of working in multiple manners of painting. When merchants like the ones referenced at the start of this essay asked for icons in the Greek and Latin styles, El Greco was an artist uniquely suited to produce both.