Everything seems so perfect… Hang on, what’s that in the foreground? And why is that lute string broken?

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re looking at Holbein’s “The Ambassadors” from 1533, here in the National Gallery in London.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:10] This is a painting that’s actually about the things we can’t see.

Dr. Harris: [0:14] On the left, Jean de Dinteville, who was an ambassador from France living in England. On the right, Georges de Selve, his friend, a bishop and also an ambassador.

Dr. Zucker: [0:25] Both of these men are in England. And Holbein, who was a Swiss painter, had moved to England because he could get work here. In fact, within a short time after making this painting, he would become the painter to the king of England, Henry VIII.

Dr. Harris: [0:38] King Henry VIII is about to break away from the Catholic Church. We know that the French ambassador was in England to keep an eye on Henry VIII during this tumultuous period.

Dr. Zucker: [0:49] We see within the painting references to the turmoil that is taking place in England. But it’s all within an even greater context.

Dr. Harris: [0:58] Let’s start with the two men. We see Jean de Dinteville on the left. He’s the one who commissioned this painting, and he’s the one whose house the painting hung in.

[1:06] He’s obviously represented as an enormously wealthy and successful man, with his fur-lined cloak and velvet and satin clothing. He holds a dagger on which is inscribed his age, which was 29. He’s a very young man.

[1:20] Holbein described his clothing with a sense of clarity and detail that we expect of that Northern tradition that Holbein comes from. Then on the right, Georges de Selve is dressed more modestly in a fur cloak. The book that he’s got his elbow on has inscribed on it his age, which is 25.

Dr. Zucker: [1:38] It is an interesting contrast. We have that dagger on the one side, and the book on the other, references which were actually quite traditional to the active versus the contemplative life.

Dr. Harris: [1:47] We’re meant to look at both of them. But even more than that, perhaps, we’re meant to look at what’s in the middle of the painting, which is all these objects on these two levels of shelves.

Dr. Zucker: [1:55] Holbein is just brilliant in his ability to render textures and the material reality of those objects. They also mean something.

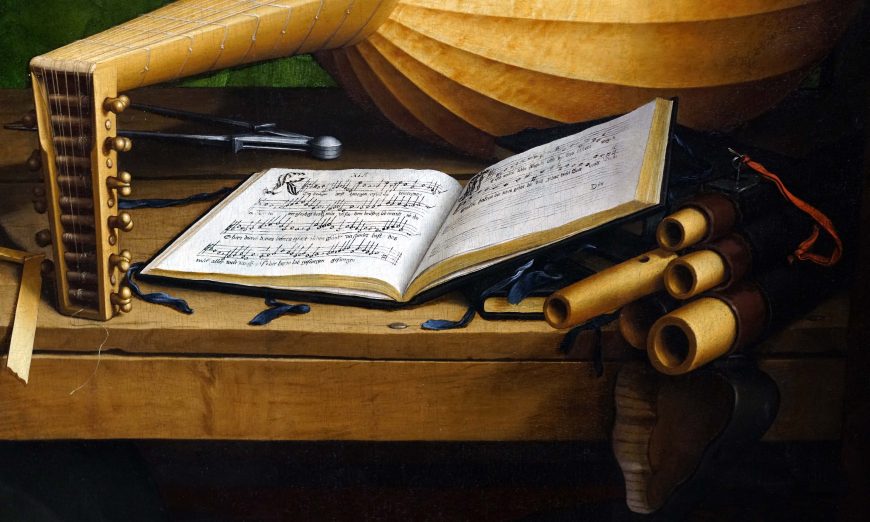

Dr. Harris: [2:03] On the top shelf, we have objects that are related to the study of astronomy and to the measuring of time. On the lower shelf, things that are more earthly. We have a terrestrial globe, and a lute, and a book about arithmetic, and a book of hymns.

Dr. Zucker: [2:16] The painting is functioning basically as a grid. On the left, you have the active life, on the right, you have the contemplative life. At the top you’ve got the celestial sphere, at the bottom, the terrestrial sphere. Look at the beautifully foreshortened lute on the bottom shelf. Lutes were traditionally objects that were rendered in order to learn perspective.

[2:35] Here, there’s this masterful representation of the way in which that lute is much shorter than it should be, because we’re seeing it on end. But if you look very closely, you can see that one of the strings is actually snapped.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] Art historians understand this as referring to the discord in the church in Europe at this time.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] That can also be seen in the hymn book, which is just below that. It’s open, and it’s so precisely painted that it can actually be read. It’s a translation of a hymn by Martin Luther, the head of the Protestant Reformation.

[3:04] All of this luxury, all of these objects, all the extraordinary fashion that they wear, all of this stands on a mosaic floor with this beautifully detailed tiling. It’s seen in perfect linear perspective.

[3:17] This is reference to an actual floor at Westminster Abbey. That floor in that church is actually a diagram, and it’s meant to represent the macrocosm, that is, the cosmic order.

Dr. Harris: [3:29] Look at the very large form that occupies the foreground.

Dr. Zucker: [3:32] I had a student once that said it looked like a piece of driftwood that had somehow been placed down oddly in the foreground.

Dr. Harris: [3:38] What we’re really looking at is an anamorphic image, a kind of image that’s been artificially stretched in perspective. When you go to the right corner of the painting, crouch down a bit…

Dr. Zucker: [3:50] …or look at it in a mirror at an angle, it’s a human skull.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] It’s something that you can’t see when you can see the other things in the painting. But it’s something you can see when you don’t see the other things in the painting.

Dr. Zucker: [4:03] Front and center in this painting, really, in a sense, the star of the painting, is this skull, which is a traditional symbol of death.

Dr. Harris: [4:10] A memento mori.

Dr. Zucker: [4:12] A reminder of death. That’s a very common element that we see in paintings. But here, we have a painting that seemed for a moment to be celebrating these earthly achievements and now seems to be undercutting it.

[4:23] If you look even more carefully in the extreme upper-left corner of the painting, peeking out from behind the curtain, you can just make out a little sculpture of a Crucifixion.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] Then we have this question that goes back to Holbein, and that is about representation. You have the lute that’s perfectly foreshortened, or that floor, that’s a perfect perspectival illusion also, so this ability to render reality so perfectly. Then you have Holbein choosing to represent the skull in an unnaturalistic way.

[4:54] Choosing to represent the earthly things in a realistic way, but choosing to represent that which is supernatural, or that which is transcendent in a way that is not according to that perfect illusionism.

Dr. Zucker: [5:07] And I think Holbein really wants us to see that contrast. Look at the relationship between the lute and the skull. The skull is distorted so extremely that it really is hard to read. But when you think about stretching something, you generally think about stretching it horizontally, or perhaps vertically.

[5:24] To do so diagonally is very particular. The lute is resting on that shelf. It really is foreshortened at an angle that is very close to the angle of the distortion of the skull. But remember, foreshortening is another kind of distortion.

[5:38] In a sense, they are both distortions. One is a distortion that creates a reality of our world, as we see. It’s a reminder that perhaps what we see is not really truth.

Dr. Beth Harris: [5:49] It’s not all there is.

Dr. Zucker: [5:50] This painting was all about what these men had achieved in life.

Dr. Harris: [5:54] And what human beings had achieved historically, for our investigation of the world. And so the two elements that are half-hidden in this painting, the crucifix and the skull, point to the limits of earthly life, the limits of earthly vision, of man’s knowledge, and the inevitability of death and the promise of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

[6:17] [music]

One of the most famous portraits of the Renaissance is without question Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors from 1533. Even today, it is a favored portrait to parody, mimic, or cite in art, TV, film, and social media, and it remains an important source for contemporary artists.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This double portrait depicts two men standing beside a high table covered in objects. On the left is Jean de Dinteville, age 29, a French ambassador sent by the French king, Francis I to the English court of Henry VIII. On the right is Georges de Selve, age 25, the bishop of Lavaur, France. They stand on an elaborate abstract pavement, which has been identified as belonging to the sanctuary in Westminster Abbey—the same space where Anne Boylen, second wife of Henry VIII, had been crowned and more recently, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge were married.

Cosmati paving, Westminster Abbey (left), marriage of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge at Westminster Abbey (right)

The painting is filled with carefully rendered details, in a clear style that we have come to identify with Renaissance naturalism of the sixteenth century. The anamorphic skull in the foreground continues to delight and surprise viewers, and to inspire artists.

Anamorphic skull (detail), Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Anamorphic skull seen at angle, Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This essay focuses on two details—the carpet and the globe—that speak about the globalized trade of the sixteenth century, and specifically European imperial ambitions and colonization.

The Anatolian carpet

Draped over the top level of the table between the two men is a carpet, usually referred to as a “Holbein Carpet” because of the artist’s fondness for painting this type of textile. This name, though, would not have been used in the sixteenth century. Instead, the carpet would have reminded observers of the place from where it was produced—in this case Turkey—which was controlled, in the sixteenth century, by the Ottomans. Anatolian carpets were popular luxury objects in Europe from the fifteenth century onward. Textiles from Turkey, as well as other parts of the eastern Mediterranean were highly sought after because of their extraordinary craftsmanship and beauty.

Carpet (detail), Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Often, so-called “Holbein carpets” display octagonal medallions, other stylized patterns, and sometimes borders with Kufic, a type of Arabic calligraphic script (which the one in The Ambassadors does not). This type of carpet became so popular in Europe, that other textile makers began to try to copy it, often with pseudo-Kufic designs intended to mimic the script.

Carpets like the one in Holbein’s painting were expensive. They figured prominently in elite European homes, and often cost as much as paintings and sculptures. Unlike today, a carpet of such expense would not be placed on the floor. It would be draped over a table, as shown in The Ambassadors, to be displayed as a beautiful object to observe and delight in. We can find similar carpets In other Renaissance paintings, often draped over parapets or tables. Occasionally such carpets are shown on the floor underneath the Virgin Mary to convey her elevated status as a holy figure.

“Holbein carpet,” 15th–16th century, wool, from Turkey (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

So why is a carpet in Holbein’s painting? The carpet is a luxury object meant to elevate the two men’s status. It also reminds us of the power and prestige of the Ottoman Empire at the time. The Ottomans were considered a threat to the European powers, even as Europeans desired Ottoman luxuries, such as carpets.

There is also likely another reason for the carpet’s appearance in the painting. Francis I, the French King, had recently aligned with King Henry VIII of England in an attempt to reduce the power of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor who controlled much of mainland Europe. Charles V was a powerful ruler, and Francis I and Henry VIII were concerned that he might try to wrest control away from them. Francis I also tried to cultivate relationships with the Papal States and the Ottomans, and he reached out to Süleyman the Magnificent, the Ottoman ruler. The carpet in Holbein’s painting may refer to the French ruler’s attempts to strengthen political ties to the Ottomans. Francis I no doubt coveted such a relationship as it would bolster his commercial ties, strengthening his ability to acquire Ottoman commodities and giving him greater access to goods from China and India that were also highly desirable.

The carpet has multiple meanings: politically, it speaks to Francis’s attempts to forge a political connection with the Ottoman ruler, and culturally, as an expensive, imported textile from the Anatolian peninsula. The carpet is a reminder that the Ottomans were an important part of European Renaissance culture.

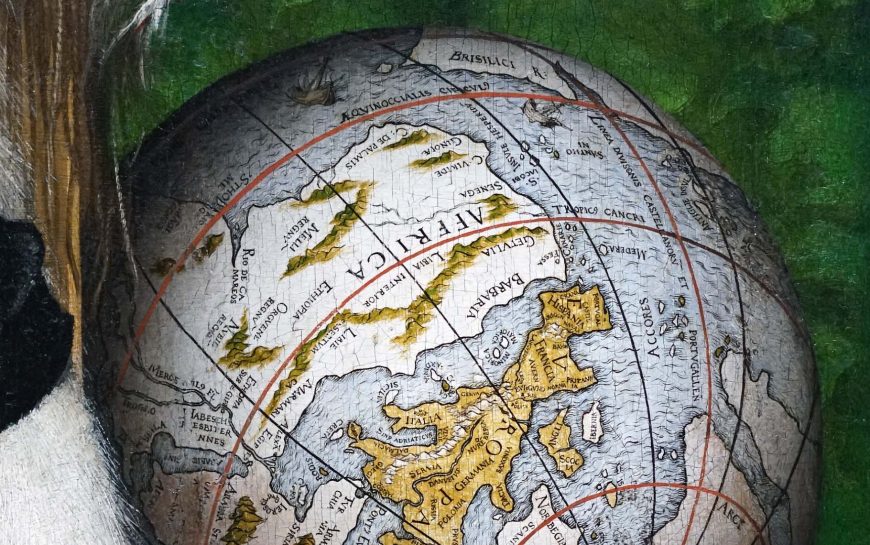

Globe (detail), Anamorphic skull seen at angle, Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The globe

On the shelf below the carpet, there are a number of intriguing objects, including a lute with a broken string, a hymn book, and a globe. The lute’s broken string is thought to reference the discord that resulted from the Protestant Reformation, which the hymn book also calls to mind. Martin Luther, who initiated the Reformation, composed the hymns shown.

Luther’s Hymn Book (detail), Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The globe, however, does not refer to the upheaval that resulted from the Reformation, but it does call to mind other types of transformations then taking place. The map on the globe is displayed upside down from a globe’s common orientation. Despite this, many parts of Europe have legibly written inscriptions. Holbein positioned Europe closest to the picture plane and painted it in a golden color to draw our eyes to it. We see Africa above, and beyond that parts of the Americas.

Interestingly, one of the legible inscriptions on the globe is “Brisillici R.” for Brazil. The visual clarity and reference to Brazil is important. The French crown made a claim to Brazil after it had sponsored an expedition to the Americas in 1522. Heading the expedition was Giovanni da Verrazano, who returned in 1524, helping France to stake a claim to lands across the Atlantic. Verrazano would return to Brazil in 1527 to collect Brazilwood, a valuable resource. The French crown attempted to establish trading posts in Brazil in order to claim control over this rich foreign land, an action that pit France against its colonial rival Portugal.

Globe (detail), Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Several red lines also run through parts of the globe in Holbein’s portrait. One, which runs through Brazil and divides the Atlantic, was the line agreed to with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty resulted in much of the Americas being granted to Spain, while Brazil was granted to the Portuguese. Another line, one that resulted from the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529 (once again between Spain and Portugal), divided the map in the other direction, giving the Portuguese the Moluccas, or Spice Islands. The inclusion of these lines reveals the importance of the competition between colonial powers for land, resources, and people, and the far-reaching implications that European maritime voyages and colonial expeditions would have across the globe.

19th-century facsimile of a 16th-century globe of the type depicted in Holbein’s The Ambassadors, 12 paper gores mounted on solid wood sphere, 54 cm (Beinecke Library, Yale)

What makes Holbein’s globe even more fascinating is that it replicates an actual globe from the sixteenth century. Holbein copied a globe such as the replica in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, from around 1526. The original was a printed globe, made possible by the revolution in print technology that had transformed Europe since the middle of the 15th century. The globe was likely printed in Nuremberg, and was popular in the 1520s and 30s. On the printed globe, there are clear references to Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe which was completed in 1522. The globe then alludes to Habsburg dominance, since Charles V, a Habsburg, had sponsored Magellan. Despite Holbein’s borrowing from the printed globe, he omits the Magellan route. It has been suggested that this was an effort by Holbein, who was aware that his patron was a subject of Francis I, to downplay Habsburg power.

Peter Apian, A New and Well-grounded Instruction in All Merchants’ Arithmetic (detail), Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533, oil on oak, 207 x 209.5 cm (The National Gallery, London, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Like the globe and the Turkish carpet, the book that rests on the table just in front of the globe also alludes to the importance of trade. Holbein’s precise manner of painting the book allows us to identify it as an arithmetic text, specifically the German astronomer Peter Apian’s A New and Well-grounded Instruction in All Merchants’ Arithmetic (Eyn Newe unnd wolgegruündte underweysun aller Kauffmannss Rechnung). The book discusses profits and losses—an important aspect of mercantilism and trade in this period. The navigational instruments on the upper shelf also point to commercial activities that sponsored travel and exchange, but also imperialist expansion and colonization. Each is an important theme in this complex painting.