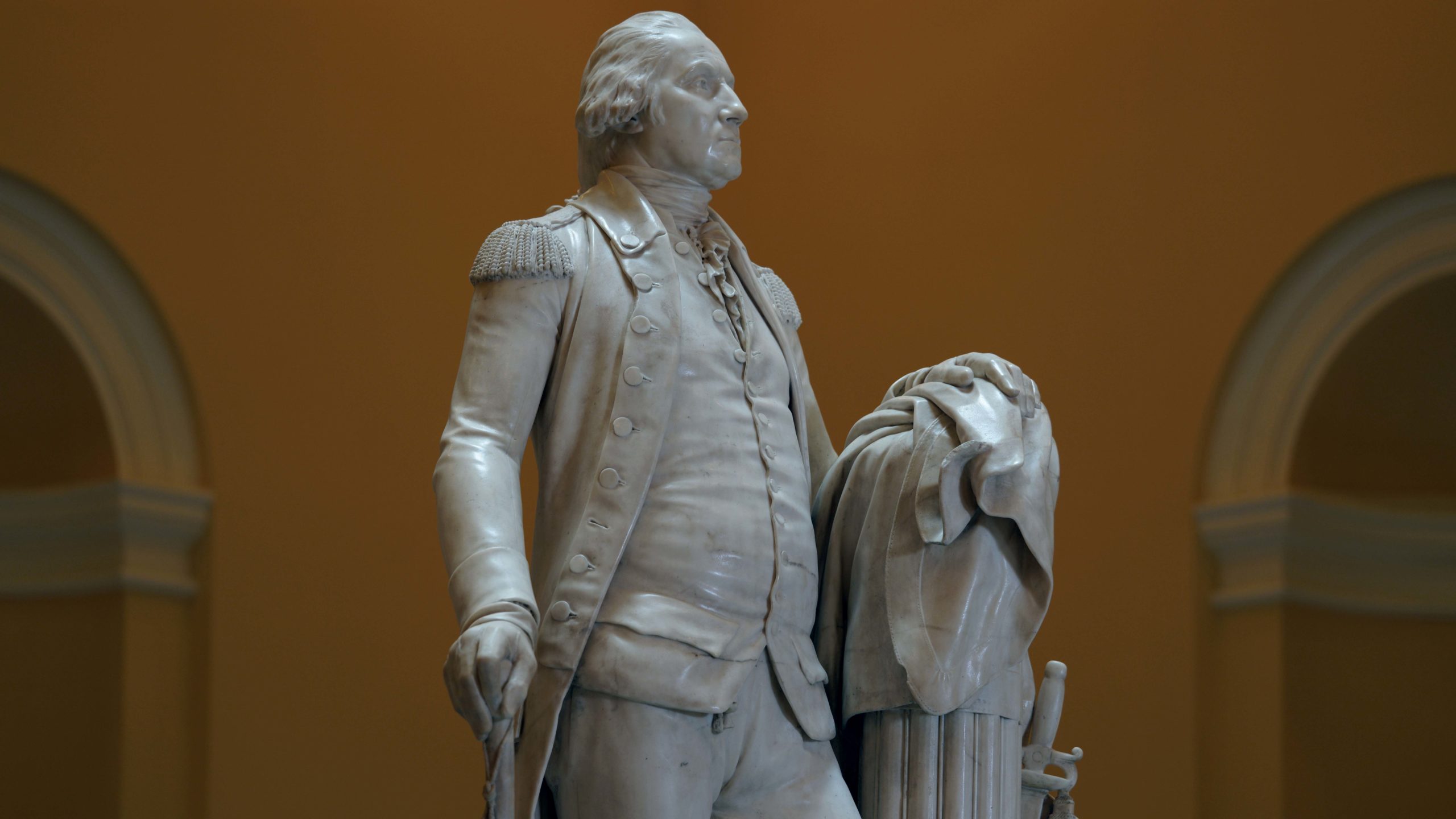

A conversation with Dr. Sarah Beetham and Dr. Steven Zucker in front of Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:10] We’re in the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, Virginia, a building that was designed by Thomas Jefferson. But we’re looking at a sculpture of George Washington that dates to the very end of the 18th century.

Dr. Sarah Beetham: [0:17] This is a sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon, who was recruited by Thomas Jefferson to create this statue at a time when there were not too many Americans who would have been ready to take on a marble sculpture like this.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] It’s not surprising that the state of Virginia wanted to honor the general who was associated with the victory of the United States over Britain and who was the first president of the United States.

Dr. Beetham: [0:41] Jefferson and Franklin brought Houdon into the project in 1784.

[0:46] At first, Houdon was going to work from a painting by Charles Willson Peale, but of course, this is a three-dimensional sculpture, and he did not feel that he was going to be able to capture Washington just from that reference.

[1:02] So in the summer of 1785 he came over to the United States, went to Mount Vernon, and visited George Washington, where he made a life mask or a cast of George Washington’s face and took measurements of his body.

Dr. Zucker: [1:10] The fact that Houdon actually was able to spend time at Mount Vernon with Washington to take a life mask is important because Washington famously did not like to sit for artists.

Dr. Beetham: [1:20] There’s so much debate when you’re thinking about the painted portraits of George Washington; the one by Gilbert Stuart, the ones by Charles Willson Peale or Rembrandt Peale. Which one looks the most like him? Which one embodied him as a statesman the best? Really, the Houdon is the one that looks the most like him because it’s based on a life mask and the sculpture becomes a model for anyone who’s going to make a statue of George Washington later on.

Dr. Zucker: [1:42] This is a sculpture that’s made in marble, and large-scale marble sculptures have a very long history. In this case, because we’re in the early years of the United States, we know that these artists were thinking back to classicism. They were thinking back to Greece, and especially to ancient Rome.

Dr. Beetham: [1:57] To us, looking at George Washington here in his military uniform, his 18th-century clothing, that looks completely normal and natural to us. But at that point, this would’ve been a radical decision. One of the real hot-button questions at the end of the 18th century was whether or not statesmen of the time should be represented in their modern clothing.

Dr. Zucker: [2:16] And so it was a real choice. We might well have seen Washington in the flowing robes of the ancient Romans, but instead we see him in contemporary fashion. But beyond the choice of clothing, there are so many other key symbols here.

Dr. Beetham: [2:29] When you’re looking at a neoclassical sculpture from the late 18th century or through the 19th century, you have to look at all the details. Of course, any marble sculpture is going to need something to lean against, because marble is not strong enough to hold itself up.

[2:47] And what George Washington is leaning against here is a bundle of sticks called the fasces, a symbol in ancient Rome of the authority of the state. Draped over that is his military greatcoat and his sword that he is giving up in order to return to Mount Vernon after the Revolutionary War is over.

Dr. Zucker: [3:00] There really is a contrast that’s being drawn by his sword, which is no longer being worn, versus the walking stick on the opposite side, which he is engaging, which he is holding, and which shows him as a country gentleman, a very clear signal that this is a man who has given up the greatest military power in the United States to go back to his plantation, Mount Vernon, and to become again a private citizen.

Dr. Beetham: [3:26] We’re seeing him right in the midst of that transition. The other detail that you don’t want to miss here is walking around the back of the sculpture. You see that not only is he hanging up his sword, but he’s also standing in front of a plow, a symbol reminding us that what he’s doing is going back to becoming once again a gentleman farmer.

Dr. Zucker: [3:43] These things taken together would have reminded well-educated statesmen of the day of a general whose name was Cincinnatus, an ancient Roman.

Dr. Beetham: [3:46] Cincinnatus was a Roman general who, in a time of peril for ancient Rome when they were being attacked by a foreign enemy, was given dictatorial powers in order to be able to suppress this invasion. And after the invasion was over, he could have tried to continue to hold on to that power. But instead of doing that, he gave up that power and went back to his Roman farm.

Dr. Zucker: [4:13] And this sets a precedent that has been critical to the ongoing democratic tradition in the United States, that a duly elected president gives up their power and ensures the peaceful transition of power to the next president.

Dr. Beetham: [4:25] That is one of the important parts of George Washington’s mythology, that he was the first American president to model that behavior.

Dr. Zucker: [4:39] So we’re seeing in the 18th-century sculpture very much in the guise of ancient Rome. But let’s broaden our scope for a moment, because it’s not just the references to Cincinnatus. It’s not just the fasces here. It’s not just the white marble that we’re seeing.

[4:44] It’s the rotunda that this sculpture is seen in, which is a smaller version of the dome of the Pantheon in Rome. The exterior of this building was designed by Thomas Jefferson, [and] mimics the Parthenon in ancient Greece.

Dr. Beetham: [4:57] At this point in the 18th century, trying to figure out what the iconography of a democratic republic is going to be was still brand-new. People like Jean-Antoine Houdon are helping the founding fathers to figure out what leadership is going to look like and what kind of architectural language and sculptural language is going to be used.

Dr. Zucker: [5:15] The heroism that we have accorded to this figure for centuries is being reexamined in light of the fact that George Washington was a slave owner and was brutal at times.

Dr. Beetham: [5:25] This is definitely a moment where we need to be thinking about what stories we have told about George Washington, and how an icon like this one helped to shape the narratives that we continue to carry forward today.

[0:00] [music]

An American hero sculpted by a foreigner

After the successful conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, many state governments turned to public art to commemorate the occasion. Given his critical role in both Virginia and the colonial cause, it is unsurprising that the Virginia General Assembly desired a statue of George Washington for display in a public space.

And so, in 1784, the Governor of Virginia asked Thomas Jefferson (another Virginian who was then in Paris as the American Minister to France) to select an appropriate artist to sculpt Washington. Seeking a European sculptor—and for Jefferson, whose Francophile sympathies were clear, preferably one who was French—was a logical decision given the lack of artistic talent then available in the United States. Through basic necessity, this portrait of an American hero needed to be made by a foreigner.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jefferson knew just the artist for this task: Jean-Antoine Houdon. Trained at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1761 when only twenty years of age, Houdon was, by the middle of the 1780s, the most famous and accomplished Neoclassical sculptor in France.

Jefferson commissioned Houdon to complete a monumental statue of Washington. Given Houdon’s skill and ambition, the sculptor likely hoped to cast a larger-than-life-sized bronze statue of General Washington on horseback, a format appropriate for a victorious field commander. However, the final product, delivered more than a decade later, was a comparatively simple standing marble.

Evidence suggests that Houdon was supposed to remain in Paris and sculpt Washington from a drawing by Charles Willson Peale. Uncomfortable with carving in three dimensions what Peale had rendered in only two, Houdon made plans to visit Washington in person. Houdon departed for the United States in July 1785 and was joined by Benjamin Franklin—who he had sculpted in 1778—and two assistants. The group sailed into Philadelphia about seven weeks later and Houdon and his assistants arrived at Mount Vernon (Washington’s home in Virginia) by early October. There they took detailed measurements of Washington’s body and sculpted a life mask of the future president’s face.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Contemporary clothing (and not a toga)

While in Virginia, Houdon created a slightly idealized and classicized bust portrait of the future first president. But Washington disliked this classicized aesthetic and insisted on being shown wearing contemporary attire rather than the garments of a hero from ancient Greece or Rome. With clear instructions from the sitter to be depicted in contemporary dress, Houdon returned to Paris in December 1785 and set to work on a standing full-length statue carved from Carrara marble. Although Houdon dated the statue 1788, he did not finish it until about four years later. The statue was delivered to the State of Virginia in May of 1796, when the Rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol was finally completed.

“Nothing in bronze or stone could be a more perfect image…”

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In time, this statue of George Washington has become one of the most recognized and copied images of the first president of the United States. Houdon did not just perfectly capture Washington’s likeness (John Marshal, the second Chief Justice of the Supreme Court later wrote, “Nothing in bronze or stone could be a more perfect image than this statue of the living Washington”). Houdon also captured the essential duality of Washington: the private citizen and the public soldier.

Washington stands and looks slightly to his left; his facial expression could best be described as fatherly. He wears not a toga or other classically inspired garment, but his military uniform. His stance mimics that of the contrapposto seen in Polykleitos’s classical sculpture of Doryphoros. Washington’s left leg is slightly bent and positioned half a stride forward, while his right leg is weight bearing. His right arm hangs by his side and rests atop a gentleman’s walking stick.

His left arm—bent at the elbow—rests atop a fasces: a bundle of thirteen rods that symbolize not only the power of a ruler but also the strength found through unity. This visually represents the concept of E Pluribus Unum—”Out of Many, One”—a congressionally approved motto of the United States from 1782 until 1956.

Washington’s officer’s sword, a symbol of military might and authority, benignly hangs on the outside of the fasces, just beyond his immediate grasp. This surrendering of military power is further reinforced by the presence of the plow behind him. This refers to the story of Cincinnatus, a Roman dictator who resigned his absolute power when his leadership was no longer needed so that he could return to his farm. Like this Roman, Washington resigned his power and returned to his farm to live a peaceful, civilian life.

Washington as soldier and private citizen

Horatio Greenough, George Washington, 1840, marble, 136 x 102 inches, National Museum of American History (photo: Gary Todd, public domain)

The statue, still on view in the Rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol, is a near perfect representation of the first president of the United States of America. In it, Houdon captured not only what George Washington looked like, but more importantly, who Washington was, both as a soldier and as a private citizen.

The enormously talented Houdon wisely accepted Washington’s advice. Indeed, Washington knew it was better to be subtly compared to Cincinnatus than to be overtly linked to Caesar, another Roman who, unlike Cincinnatus, did not surrender his power.

To compare Houdon’s statue to Horatio Greenough’s 1840 statue of Washington only makes this salient point more clear. With the sitter’s urging, Houdon opted for subtlety, whereas Greenough decided two generations later to fully embrace a neoclassical aesthetic. As a result, Houdon’s statue celebrates Washington the man, whereas Greenough deified Washington as a god.